if Griselda Pollock`s GENERATIONS AND GEOGRAPHIES is

advertisement

ART N72 .F45 G46 1996 GENERATIONS AND GEOGRAPHIES possibly precise a few chapters on some of

the non-U.S./European artists [Re-Hyun Park, Jin-me Yoon, Shimdao Yoshiko, possibly another].

ART N7260 .A818 1996

Dinah Dysart and Hannah Finnk, ASIAN WOMEN ARTISTS

ART N7304 .E97 precis of at least one of the modern artists in Sinha, Expressions & Evocations

ART/SAL NX165 .O94 1992 Craig Owens on modernism and feminism is available, copy & highlight

ART/SAL NX180 .F4 H4 NO.21-24 1987-1989

TITLE: Interview [with Trinh T. Minh-ha, filmmaker]

AUTHOR: Hirshorn, Harriet A.

SOURCE: Heresies, 22:14-17 (1987)

ART NX164 .B55 P37 1990

Passion : discourses on blackwomen's creativity / edited by Maud Sulter. 1990.

ART NX180 .F4 T36 1998 Ella Shohat, Talking Visions: Multicult Fem Transnational Age MIT 1998 0r 99.

ILL ??

4. I mention Maud Sulter's photo exhibit MUSES, which used African American women as the muses of

creativity - got it from Imagining Women, but they have only a passing reference. if it is not too hard to find a

description or review of the work, that would be great. not highest priority re: time spent looking

Malvern, Sue, `The muses and the museum: Maud Sulter's retelling of the canon', in eds. Michael Biddiss and

Maria Wyke, The Uses and Abuses of Antiquity (Bern: Peter Lang, 1999) * (UCI?)

JC571 .B6735 1996 WOMEN RESHAPING HUMAN RIGHTS, M Guzman Bouvard [for later, chap 15 rev

SEARCHING PR275 .W6 S86 2000 Summit, Jennifer. Lost property : the woman writer and English literary

history, 1380-1589 [on women writers in early modern england] - if not available, buy at bookstore

SEARCHING PR6069 .O78 M3 1999 Soueif, Ahdaf. The map of love / Ahdaf Soueif. 1999.

reviews or interviews or reviews essays re: Egyptian feminist writer living in London, last name SOUEIS,

author of MAP OF LOVE (99) and EYE OF THE SUN (92—780 pages!). online links are fine.

PS3535 .U4 O75 1992

Out of silence : selected poems / Muriel Rukeyser ; ed. Kate Daniels

minor question: what is the date of Muriel Rukeyser's poem "Kathe Kollwitz"? - and since i need to

check the spacing for her poem MYTH, might as well get a book of her poems with both from the library,

if they are in the same volume.

PS147 R87 1995 Joanna Russ, To write like a woman: essays in feminism and science fiction

PS153 .M4 S25 1990A Saldivar-Hull, FEMINISM ON THE BORDER - precis and/or intro, reviews

PT111 .P38 1997 Gendering German studies : new perspectives on German literature and culture / edited by

Margaret Littler. 1997.

5. I have an old reference for an anthology of German women writers with an introduction ed by

Herrmann and Spiz - bakc in 80s, I think. If there is a more recent anthology or overview with a quick

and dirty introductory essay, go for it. if not, don't worry.

PT167 .H57 2000 A history of women's writing in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. 2000.

PT405 .A17 1993

Adelson. 1993.

Adelson, Leslie A. Making bodies, making history : feminism & German identity / Leslie A.

S480.842 .M46 1998 anthologies of writing by Indian women edited by Ritu Menon - if is a recent one that gets

into the 1990s and especially if she has an intro overview, i'd like to take a look.

KING, TONI C.; BUKER, ELOISE A. "To and Fro": Deepening the Soul Life of Women's Studies Through

Play.(Critical Essay) NWSA Journal v13, n1 (Spring, 2001):105. Pub type: Critical Essay

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/nwsa_journal/v013/13.1king.pdf

RECALLED RLCP recall the Trinh Minh-Ha book, When the Moon Waxes Red, I'll look at it - hard to tell from

reviews –

literature, esp non U.S., after 1980s. I have complete runs of Signs and Feminist Studies at home - if you can

find any articles in them listed in data bases I can easily read them - it would be easier than simply reading

through all the contents. looking for any literary articles [not nec. theory, just what is happening out there,

but lit crit is okay] that cover the 1990s!

PR6069 .O78 M3 1999 Soueif, Ahdaf. The map of love / Ahdaf Soueif. 1999.

reviews or interviews or reviews essays re: Egyptian feminist writer living in London, last name SOUEIS,

author of MAP OF LOVE (99) and EYE OF THE SUN (92). online links are fine.

http://www.cairotimes.com/content/culture/suef.html (Interview)

Costantino, Roselyn, “And She Wears It Well: Feminist and Cultural Debates in the Work of Astrid Hadad, in

Arrizon, Alicia (ed.)--Manzor, Lillian (ed.); 444 pp.; Latinas on Stage: Practice and Theory; Third Woman,

Berkeley, CA Pagination: 398-421 Third Woman, Berkeley, CA

AP4 .T45 Stacks Said, Edward W. Map of Love.(Review) TLS. Times Literary Supplement, n5044

(Dec 3, 1999):7 (1 pages).

Pub type: Review

028.8 B725

Booth, Marilyn In the Eye of the Sun. World Literature Today v68, n1 (Winter,

1994):204 (2 pages).

Call Kathy Kerns—index Feminist Studies & Signs?

Bookstore: Showalter, Elaine. Inventing herself : claiming a feminist intellectual heritage / Elaine Showalter.

2001. [HQ1154 .S527 2001

PR275 .W6 S86 2000 Summit, Jennifer. Lost property : the woman writer and English literary history,

1380-1589 [on women writers in early modern england] - if not available, buy at bookstore

1. Magazine & Journal Articles

Author: KING, TONI C.; BUKER, ELOISE A.

Title: "To and Fro": Deepening the Soul Life of Women's Studies Through Play.(Critical Essay)

Journal: NWSA Journal, v13, n1 (Spring, 2001) :105 .

Publication Type: Critical Essay Subfile: Academic Index Subjects: Women's studies--Criticism, interpretation,

etc.

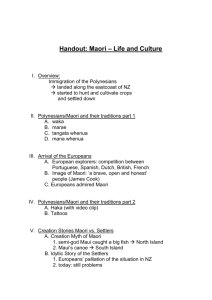

Author: Diamond, Jo Title: HINE-TITAMA: MAORI CONTRIBUTIONS TO FEMINIST DISCOURSES AND

IDENTITY POLITICS.(Critical Essay)

Journal: Australian Journal of Social Issues, v34, n4 (Nov, 1999) 301 .

Abstract: Feminist discourses attend to the experiences of women in many social spheres, including that of the

artworld. In this paper I, as a Maori woman, offer an outline of Postcolonial Maori Feminism that complies with

the cultural theorist Homi Bhabha's notion of 'Post-colonial criticism'. The connection between feminist

discourse and the accomplished Maori artist Robyn Kahukiwa has not been strongly emphasised in current

published literature. The cultural context that Robyn Kahukiwa refers to in her art is, primarily, that of Maori

women. I argue, by using one exemplary picture entitled Hine-Titama, that Robyn Kahukiwa and her artwork

align with the work of some other Maori feminists. I also posit an association between Kahukiwa and some

examples of 'non-Maori' feminist writing that furthers our understanding of cultural identities based on gender

and race. I refer to those cultural identities as they relate to Maori women in New Zealand.

COPYRIGHT 1999 Australian Council of Social Service Abstract: 'Post-colonial criticism bears witness to the

unequal and uneven forces of cultural representation involved in the contest for political and social authority

within the modern worm order'. (Homi Bhabha 1994, p. 171)

COPYRIGHT 1999 Australian Council of Social Service Hine-Titama 1980

Kahukiwa's picture entitled Hine-Titama (see Figure 1) was completed as part of the exhibition Wahine Toa

(Women of Strength) in 1980 (Kahukiwa & Grace 1991, p.10). This exhibition emphasised the importance of

female characters in Maori mythology or, as one observer noted, Üit attempted to redress the portrayal of

women as shadowy figures in conventional Pakeha White versions of Maori mythology by giving their immense

personalities full due' (Kirker 1995, p. 4). Another observer noted that Üseveral of the "Wahine Toa" images

have subsequently been "canonised" as "icons" of New Zealand art' (Mane-Wheoki 1995, p. 12). Hine-Titama

qualifies as a candidate for such canonisation due to its wide exposure through the New Zealand media (for

example Baughen 1982; Menehira 1982; Te Awekotuku 1991) and its use as the cover picture for the book

(Kahukiwa & Grace 1991) that developed from the Wahine Toa exhibition. In this paper, I describe of the

painting's content and form so that a critical analysis can follow. Notions of interdependency and

complementarity in Maori cosmology have been aptly emphasised in published literature (see Marsden 1975;

Kawharu 1975). Such work indicates a generally held (rather than feminist) interpretation of complementarity in

Maori cosmology. With such work in mind I discuss ways in which female roles within the complementarity of

this Maori cosmos are highlighted. My description necessarily begins with an account of some Maori mythology.

Hine-titama is known as the Üdawn-maid' in some accounts of Maori mythology, including the book Wahine Toa

(Kahukiwa & Grace 1991, p. 70). In records of Maori cosmogony (Best 1952, p. 41; Te Rangi Hiroa 1982, p.

453) Hine-titama is considered to be the mother of all human beings. She is one of three main interconnected

manifestations of the female element (uha) in Maori cosmology. The other two manifestations are Hine-ahuone, whom the male god Tane fashioned from the earth to become the first female form, and Hine-nui-te-po who

presides over after-life. Maori male deities sought uha as an indispensable part of the creation of human beings

(Best 1952, p. 41). In this cosmogony, Hine-titama represents the female component of human existence and

procreation. She is also, however, an offspring of the sexual union between Tane and Hine-ahu-one. After

producing a number of children with Tane, and later realising the incestuous nature of her relationship with him,

Hine-titama fled in shame to another dimension called Te Po, one of death rather than life, and she became

Hine-nui-te-po. There is, however, an inter-dimensional quality about these three female figures that mirrors the

three parts of a Maori cosmological order: ÜMaoris (sic) do not accept the idea that the universe is limited to the

world in which men live and die. Instead they see the World of Men as existing in relation to two other realms,

Te Po night and Te Rangi day ' (Merge 1976, p. 55). The three female manifestations represent godly and

earthly realms, day and night, and also an interdependent cycle that includes conception, pregnancy, life and

death. For the Wahine Toa exhibition, Kahukiwa produced paintings of all three of these female figures. Each

work bears the name of its featured deity.

Figure 1 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED

In Kahukiwa's picture that takes Hine-titama's name as a title, the artist presents the goddess as a young Maori

woman. Her head and shoulders are realistic in appearance although her facial features may be seen by some

viewers as more caricatured than realistic. Similarities to the autobiographical features in some of Frida Kahlo's

paintings denote that artist's acknowledged (Mane-Wheoki 1995, p. 10) influence on Kahukiwa.

The texture of the Hine-titama's hair and the indentations of her neck and upper torso are realistic in

appearance. The form of her body becomes more abstract further down.

A highly stylised male figure, able to be viewed as both within and immediately in front of Hine-titama's body, is

a dominant feature of the painting. This figure's appearance is ambiguous because the upper sections of the

figure's arms appear to be outside Hine-titama's armpit area yet the remainder of his arms seem more within

and part of her arms. The black and white, green-eyed figure has long, skeletal arms that extend to the bottom

of the picture. His head, torso and genitals appear to have the tattoo-like markings that can be seen on figures

in many examples of Maori carving (whakairo). Hine-titama's body also extends to the bottom of the picture and

its form changes into a red placenta-like mass.

The entire length of space that extends beneath Hine-titama's arms is ambiguous. Within it, on her right side, is

placed a human foetus enclosed in a sac and with an umbilical cord that seemingly stretches back into the

middle of Hine-titama's body. Within a corresponding space to her left is a lizard. These two spaces seem to

have a directional function where the unborn child descends and the lizard climbs.

Above this symmetrically placed collection of figures is a large halo-like circular radiating design that surrounds

Hine-titama's head. The pattern appears three-dimensional and brings to mind the curvilinear patterns of Maori

art, especially whakairo. The double spiral form (Te Rangi Hiroa 1982, p. 315) of whakairo can be read into the

Ühalo', as can a representation of the rays of the sun. The halo's gold-coloured appearance that it shares with

the double spiral form accentuates the golden aura surrounding Hine-titama's body. Dawn is suggested by a

thin red line above a green hilly landscaped background and a white skyline gradually breaks into blue then

appears to encroach on a black starry sky. The blackness of the disappearing night sky is mirrored in the lowest

portion of the painting but the eye descends to this point through a gradation of layers that are earth-coloured.

The number of these layers equals that of the rings that make up the Ühalo' around Hine-titama's head.

An interpretation based on knowledge of Maori symbolism is necessary to gain a full appreciation of the

painting's meaning. The corresponding number of rings and ground layers is significant. The artist considers

the rings to be part of a spiral that: Üportrays both an important element of traditional Maori carving, and ten

overworlds. The ten underworlds are shown as horizontal layers, beginning with the grass and topsoil and

going through various stages until they reach Meto, the extinct' (Kahukiwa & Grace 1991, p. 70).

This reference to a multi-layered Maori cosmos corresponds with layers of the three dimensions of Maori

cosmology mentioned earlier. Life, death, day and night are also represented symbolically by the foetus and

lizard. Kahukiwa's explanation is helpful in decoding this symbolism: ÜThe black, stylised figure which forms the

bones of Hine-titama's arms, symbolised Tune, who is both her own father and the father of her children. The

foetus represents mankind, the children of Hine-Titama and Tune, and the lizard is a disguise Maui a wellknown heroic figure in epical Maori myths adopted when he tried to conquer death' (Kahukiwa & Grace 1991, p.

71).

A broader, though related, interpretation is also possible: the descending foetus is a metaphor for birth whereas

the ascending lizard metaphorically marks a return to death. This life-death cycle is continuous. A sense of the

inter-connectedness of day and night, life and death, surround a female entity who is inseparably linked to a

male entity, the god Tane. Hine-Titama is symmetrically composed suggesting harmony and balance. The

relationships between male and female, life and death, night and day originate from a Maori cosmological

context that is not organised so distinctively. These pairs are juxtaposed in Maori cosmology suggesting

something akin to Üyin-yang' interdependency rather than an opposition.(1) This interdependency is reflected in

some Maori feminists' views of the relationship between Maori men and women discussed later.

A value-system based on notions of good and evil that corresponds to ideas of light and darkness is, however,

absent in Hine-Titama. This absence confirms Metge's (1976, p. 56) observation of Maori cosmology: The

relation of Te Rangi and Te Po is not one of conflict and negation, as it is between Heaven and Hell, but one of

complementarity. As light cannot be comprehended except in relation to darkness, as life cannot be

appreciated except in relation to death, so Te Rangi and Te Po define and complete each other. Together they

are united as spiritual realms in contrast with the World of Men, alternatives that are equally possible and even

interchangeable, not mutually exclusive (my emphasis).

Hine-Titama represents a manifestation of the female element in a Maori cosmogony that considers this element

an indispensable part of human existence. The female deity represents life and death and a cosmological

connection between three dimensions inhabited by spiritual entities, ancestors and those of us who continue to

inhabit a more physical world. In Hine-Titama this deity is one of compassion, understanding and benevolence.

In Maori terminology she is filled with Üaroha' which can be translated as a combination of Ülove' and

Ücompassion'. I will return to this concept of aroha later.

The use of a painting style in Hine-Titama that is design-based and illustrative belies its instructive and symbolic

purpose. Hence there is a need for accompanying texts and artist's notes, especially for those viewers who

have no prior knowledge of Maori myths, cosmogony and cosmology. The painting's ability to engage the

viewer could be limited to those with this knowledge, as may its potential to impress some critics.

The Maori Goddess and Maori Feminism

References to Ügoddesses' and other female entities from Maori legends and mythologies have been used

recently in a highly political fashion in New Zealand. The governmental policy analyst and performance artist,

Hinemoa Awatere (1995), for example, writes about Maori women of her own genealogical lineage. In doing so,

she provides, from a feminist standpoint, a reinterpretation of records of Maori mythology (for example, Alpers

1964, p. 23) that distinguish the roles of male deities in Maori cosmogony above those of females. Kahukiwa's

Wahine Toa paintings reflect Awatere's revisionism and also invite respect for female Maori deities and for Maori

women. The incorporation of female deities into writing and art supports the idea of an innate strength in all

Maori women. This incorporation is used strategically, in a political effort to raise the morale of Maori women

and to lobby for recognition and respect for Maori women in New Zealand society: ÜWhat it is all about is

affirming the unlimited potential of Maori women. It is about affirming that as Maori women we hold all the

knowledge that we need within us, and that no white government or white legal system -- no one in fact but

ourselves -- will actually make any changes in our lives' (Awatere 1995, p. 38).

In her writing, Awatere entreats all Maori women to participate in a political struggle. Her plea would appeal to

many Maori women who feel disadvantaged by the current social climate in New Zealand, and emulates the

revisionist messages in Kahukiwa's Wahine Toa paintings and her other artwork. Like Awatere's writing,

Wahine Toa exalts Maori female mythological figures. Figures such as Hine-titama are used symbolically to

highlight the strength and challenges of Maori women in everyday life. Regardless of the origins (Maori or nonMaori) of the referents that Kahukiwa adopts, her art can be placed in the milieu of current Maori feminist

political concerns.

The inclusion of male figures in Kahukiwa's paintings throughout most of her career indicates her willingness to

engage in a Üunified struggle with Maori men' (Larner & Spoonley 1995, p. 53).

Kahukiwa's primary focus in her painting, however, has been on engendering pride and boosting morale

amongst Maori women. Kahukiwa's paintings are, therefore, politically based though she has made no attempt

to produce negative images of relationships, such as those of domestic violence or acts of racism, between

Maori women and men or between Maori people and non-Maori people. She appears to leave that type of

imagery to other artists and may invite some criticism for doing so from commentators including other Maori

feminists. To date, however, this kind of criticism has not been published. Nevertheless, Kahukiwa represents

one strand of Maori feminist discourses. She contributes to a political movement that can be called ÜMaori

feminism' because of its particularised attention to Maori women.

Main Concerns of Maori Feminism

There is a common and recurring theme in the artistic production and literary publications of Maori women that

concentrates on the social problems Maori women have endured, succumbed to and/or resisted in the past and

continue to experience today. Maori women experience a higher incidence of illness and premature death,

higher crime rates reflected in penal detentions, and greater involvement in domestic violence and homicide

compared to other groups in New Zealand. Also, there is a higher unemployment rate among Maori women

with a corresponding lower educational attainment level and a higher dependence on Government Social

Welfare benefits. Many Maori women currently live in socio-economically disadvantaged situations compared to

Maori men and non-Maori New Zealanders.

As noted earlier, Awatere (1995) and Kahukiwa address Maori women living today, ancestral Maori women and

deified Maori women in order to inspire political action against a particular social order.

This order can be called Üpatriarchal' at the very least because Government statistics show that men in New

Zealand society have more job and education opportunities than women.

These opportunities afford men an unequal advantage in New Zealand's capitalist economy. For example, men

hold most of the powerful decision-making positions in that society, the current holder of the office of Prime

Minister notwithstanding. Nevertheless, Awatere's writing, and Kahukiwa's art, is not intended to be separatist

or exclusive.

Their endeavour is directed more towards equality between Maori women and men than any oppressive

matriarchal Maori alternative.

Representation and Identity

The Maori feminist writer, Irihapeti Ramsden (1995) proposes a Maori feminist agenda that fosters the

preservation of and respect for Maori culture without imposing a policy of segregation between Maori men and

Maori women. Kahukiwa contributes to Ramsden's agenda as none of the published examples of her artwork

explicitly attack Maori men. Hine-Titama encompasses both male and female cosmological elements.

Kahukiwa's work can be analysed in Ramsden's feminist terms that do not foster the separation of Maori women

from men and is in keeping with the interdependency of female and male in Maori cosmology.

Maori film critic and educator, Leonie Pihama (1994, p. 240) includes herself in a Ücritical struggle by Maori

people that is related to our images and the ways in which we are presented and re-presented by the dominant

voice' (my emphasis). The Ücritical struggle', that Pihama refers to, is against visual misrepresentation of Maori

people and is part of a deconstructionist effort to uncover underlying assumptions upon which our

epistemological positions are based ... that necessitates a depth of analysis that reaches into questions which

seek to unmask modernist metanarratives that validate the belief that eurocentric constructions of history, and in

particular of the histories of the colonised, present the Üone true' interpretation (pp. 241-2).

Pihama's observation of a Maori Ücritical' struggle can be used as a model to combat inaccurate or inadequate

representations of Maori people. Kahukiwa's paintings, and my interpretation of them, can be placed in the

same context of Ücritical' struggle; a struggle towards a more complete discourse than that which currently

exists about her work and is available for public consideration.

The Creative Process and Role-Juggling

The Maori feminist Education scholar Kathie Irwin (1995, p. 10) fosters the realisation of artistic potential

amongst Maori women, and its public recognition, though she cautions: Knowing what we do about the reality of

Maori women's lives, being creative is probably the last thing many would expect Maori women to aspire to, let

alone dabble in; even, dare I say it, excel at!

As a group, the demographic and statistical profile of our lives is depressing, indeed alarming, on almost every

social, economic and educational indice.

In Irwin's (1995, p. 12) opinion ÜWriting, painting, singing about our worlds is a critical part of Maori women's

survival kit!'. Irwin (p. 11) refers to the family life and internationally-recognised work of Maori writer Patricia

Grace as a role model for creative endeavour undertaken in concert with a demanding number of other

responsibilities such as motherhood and housekeeping on a low budget.

Irwin's views can be related to the art and life of Robyn Kahukiwa. Kahukiwa combines both artistic and political

endeavour in her art and this practice coincides with family demands. Painting began as an activity Kahukiwa

undertook at home: ÜAroand 1967, as a housebound young mother ... she succumbed to an impulse to paint'

(Mane-Wheoki 1995, p.10). Grace and Kahukiwa's (1991) collaboration in the book Wahine Toa is a fitting

testimony to the creative endeavour of both the writer and the artist given their family responsibilities. Their

book, along with other examples of their creativity, could inspire other Maori women, including many mothers, to

use their creativity inside and outside their homes if they are not already doing so. It could also inspire other

people besides Maori women. Irwin's commentary (1995) is also inspirational as it may encourage more Maori

women, and other people, to engage in feminist discourse that addresses art criticism and promotion.

I conclude from this comparison of the work of Maori feminists and Kahukiwa's art that they are comparable and

also intersect. However, despite Irwin's reservations (quoted by Larner& Spoonley 1995, p. 54) about

international forms of feminism, which she suspects may have similar potentially detrimental consequences as

those of British colonisation, other Üpost-colonial' (to borrow from Bhabha's definition quoted earlier) feminist

theory -- critically appraised -- can be aligned with Maori feminist endeavour.

Beyond Maori Feminism

I emulate the feminist scholar Vicki Kirby's (1993, p. 2 l) Ügrafting, rereading and recycling' of Anglo-American

feminism and cultural criticism undertaken by Australian feminists by highlighting areas where Kahukiwa, Maori

and some non-Maori postcolonial feminist discourses intersect. These areas are entitled ÜDifference' and

ÜComplementarity'.

Difference Political Objectives

The promotion in New Zealand of a Üspecial' or essential cultural identity for Maori women as a political strategy

against social disadvantage, particularly in relation to the art of Robyn Kahukiwa and the writing of Hinemoa

Awatere, can also be analysed in relation to the following comment: ÜSpecialness as soporific soothes,

anaesthetizes my sense of justice; it is, to the wo/man of ambition, as effective a drug of psychological selfintoxication as alcohol is to the exiles of society' (Trinh 1989, p. 88). This comment implicitly warns of the

danger of being lulled into egotistical complacency when undertaking political action that adopts an oversimplistic notion of a cultural identity named ÜMaori woman'. This complacency could result in dogma that

ignores, or chooses to forget, the variety of experience and interests, political or otherwise, among those who

identify as Maori women.

Cultural theorist and film-maker, Trinh T. Mirth-Ha (1989, p. 82 & p. 95) also offers a feminist perspective of

those notions of cultural difference that separate ÜMaori' from ÜNon-Maori', ÜEast' from ÜWest' and ÜFirst

World' from ÜThird World': Ü"difference" is essentially "division" in the understanding of many. It is no more

than a tool of self-defense and conquest. You and I might as well not walk into this semantic trap which sets us

up against each other as expected by a certain ideology of separatism.... Difference as uniqueness or special

identity is both limiting and deceiving'. It is not surprising that in an effort to promote an understanding and

appreciation for Maori culture, Kahukiwa and other Maori feminists may appear to promote representations of

Maori women that, in Trinh's terms, only convey Üdifference as uniqueness or special identity'. Kahukiwa and

Awatere's use of essentialist notions of Maori womanhood based on female Maori deities as discussed earlier

could seem, to some people, to verge on a form of ethnocentricity that could discourage wider, more

international, support for their political effort.

Some dissident opinions among women who identify as Maori, but feel alienated by Kahukiwa and Awatere's

portrayals of Maori women, may also fracture an otherwise resolute feminist political lobby that supports the

rights of Maori women. I am thinking, in this instance of women who, due to their ideological (for example

Christian or other religious and/or political) beliefs, may not support Kahukiwa and Awatere's promotion of Maori

mythology.

It is, however, necessary to remember that Kahukiwa and Awatere are advocating equal rights for and selfrealisation amongst Maori women. Therefore, their representations of Maori women are strategically political.

In this regard Kahukiwa, Awatere and the other proponents of Maori feminist discourse mentioned earlier,

intersect with elements of non-Maori postcolonial feminist discourse. For example, the well-known feminist

scholar Gayatri Spivak's (Spivak & Rooney 1994, p. 153) notion of a Üstrategic use of positivist essentialism in

a scrupulously visible political interest' follows this form of political action. This notion also has particular bearing

on the critical assessment of Üindigenous' art that can be undertaken by those of us in academic circles who

advocate social equality.

Deconstruction

Spivak (Harasym ed. 1990, pp. 56-58) also makes a plea to proponents of literary criticism, warning against

condescension and over-generalisation in the political involvement of academic scholars: There is an impulse

among literary critics and other kinds of intellectuals to save the masses, speak for the masses, describe the

masses. On the other hand, how about attempting to learn to speak in such a way that the masses will not

regard as bullshit.... One ought not to patronize the oppressed ... Unlearning one's privilege within the

academy is very different from clamoring for anti-intellectualism, a sort of complete monosyllabification of one's

vocabulary within academic enclosures ... one's practice is very dependant upon one's positionality, one's

situation ... the prime task is situational anti-sexism, and the recognition of the heterogenity of the field.

Spivak's (Spivak & Rooney 1994, p. 156) argument supporting a deconstructionist form of analysis also

pertains to my role as a cultural commentator and interpreter who undertakes a deconstructionist analysis of

Kahukiwa's art: What I am very suspicious of is how anti-essentialism, really more than essentialism, is allowing

women to call names and to congratulate themselves.... if I understand deconstruction, deconstruction is not an

exposure of error, certainly not of other people's error. The critique in deconstruction, the most serious critique

in deconstruction, is the critique of something that is extremely useful, something without which we cannot do

anything. That should be the approach to how we are essentialists (my emphasis).

Spivak's argument provides us with some salient advice. Deconstruction of cultural referents such as art can

take place without discouraging further artistic endeavour because of an unnecessary or over-zealous

Üexposure of error', to requote Spivak. I certainly aim to encourage and promote the work of Maori women

artists such as Kahukiwa and I believe this can be achieved without self-congratulation. To borrow Spivak's

terms, my Ücritique' of Kahukiwa's art involves an attempt to comprehensively understand her art as it is

Üextremely useful' in interpreting and promoting some aspects of the cultural identity of Maori women in New

Zealand.

Intersubjectivity

My analysis of Kahukiwa's art and feminist discourses is one example of many possibilities of an academic

involvement in identity-based politics and theory that depends on recognising the subjective position of a

researcher. Trinh (1989, p. 90 & 94) points out a diversity in the Üsubject' position beginning with a critique of a

eurocentric perception of an Üauthentic' unchanging self: The differences made between entities comprehended

as absolute presences -- hence the notions of pure origin and true self -- are an outgrowth of a dualistic system

of thought peculiar to the Occident (the Üonto-theology' which characterizes Western metaphysics).

They should be distinguished from the differences grasped both between and within entities, each of these

being understood as multiple presence. Not one, not two either. ÜI' is, therefore, not a unified subject, a fixed

identity, or that solid mass covered with layers of superficialities one has gradually to peel off before one can

see its true face. ÜI' is itself infinite layers (1989, p.

94).

Therefore, I (the ÜI' of Trinh's Üinfinite layers'), in analysing artistic expression, such as Kahukiwa's art,

endeavour to adopt a multiple perspective without attempting to Üspeak' about the art, or Kahukiwa, in absolute

terms. I consider this approach to be one that requires some sense of a fluid inter-subjectivity between myself

and Kahukiwa. My approach involves a rigorous analysis of Kahukiwa's art; one that is not seamless and one

that invites debate with other commentators.

If Maori and non-Maori feminist scholars heed Spivak and Trinh's caution to avoid over-generalisation, some

room remains for a feminist-based drive, both within and beyond academic institutions, to analyse all forms of

oppression in New Zealand society, not only those that adversely affect women. The work of Irihapeti

Ramsden, referred to earlier, which does not emphasise a separatist delineation between Maori men and

women, indicates that work in this direction has begun in Maori feminist discourses.

On this note, I wish to turn to an emphasis on complementarity rather than difference in postcolonial feminism.

Complementarity

I must, at the outset, reaffirm my earlier observation (Diamond 1998, p. 43) that Maori women have a history of

engagement in political action in New Zealand. This activism does not indicate Maori women's passivity and

compliance in New Zealand's patriarchal society. Indeed, Maori women can be seen as major players in the

production of a Maori identity that is partly based on political activism, regardless of the fact that they do not

necessarily share the same experience of hardship, subjugation or oppression. Kathie Irwin's recommendations

for encouraging creativity amongst Maori women that begins in the home also indicates not only her own

political activism but the creative and political endeavour that currently exists amongst some Maori women

artists and writers. While Irwin's comments are encouraging, more work needs to be done towards the

realisation and critical appraisal of the artistic potential of many Maori women.

Echo, Narcissus and the Aporetic Position

I use Maori mythology as part of a process of describing the role of a critic who lives in a Ücolonised' society

such as New Zealand. Similarly, Gayatri Spivak (Spivak & Papastergiadis 1991, p.66) interweaves references to

Greek mythology with a potential for critical analysis to use well-defined Üspaces' of inquiry that exist between

the Ücoloniser' and the Ücolonised': We are shuttling between Narcissus and Echo: fixating upon the prefixed

image, a pre-fixed staging, saying to other women within the culture that is how we should be identified. On the

other hand, the construction of ourselves as counter-echo to the Western dominance, we cannot in fact be

confined to behaving as we have been defined. Where there is a moment of slippage there is also a robust

aporetic position, rather than being either the self-righteous continuist narcissism in the name of identity, or the

message of despair of nothing but Echo (my emphasis).

An ‘aporetic position' between Spivak's ‘Echo and Narcissus' could be favourably compared to Leonie Pihama's

call for Ücritical struggle' against the misrepresentation of Maori women that I referred to earlier. Spivak's

Üshuttling, aporetic position' intersects with Pihama's observation that there needs to be a revised critically

based discourse about the representation in art and other cultural media of Maori women. It could be argued

that Kahukiwa's artwork incorporates a certain feminist perspective based on an introduced colonial discourse

and that the Maori Üauthenticity' of her art is questionable. Be that as it may, it requires rigorous and

demanding involvement in Pihama's Ücritical struggle' from Spivak's Üaporetic' position to accurately determine

and understand the scale of this incorporation in Kahukiwa's art. There is a vital, yet demanding, current need

for critically based assessments, and in some cases reassessments, of all representative images of Maori

women.

Aroha: an Open ‘Conclusion'

In order to reitierate and enhance the concepts of difference and complementarity presented, I wish to return to

the concept of aroha. The aroha described in relation to the Ügoddess' of Hine-Titama intersects with the views

of Black American feminist and cultural theorist bell hooks (1994, pp. 243-6) who asks, using the words of the

famous black', female' singer Tina Turner, ‘What's love got to do with it?' and makes the following comment on a

‘love ethic' that should be incorporated into emancipatory, feminist or otherwise, political action: ÜThe absence

of a sustained focus on love in progressive circles arises from a collective failure to acknowledge the needs of

the spirit and an over-determined emphasis on material concerns. Without love, our efforts to liberate ourselves

and our world community from oppression and exploitation are doomed' (my emphasis). There is immense

aroha in hooks' statement, where she focuses on spiritual needs amongst human beings. Along with that of

other feminist discourses I have described, hooks' advice may be taken by those of us who engage in Pihama's

‘critical struggle'. While my description of feminist theory focuses mostly on women, this theory de-emphasises

separatist, anti-male politics. This politics and feminist theory relates more to recognition of situation-based

variety in human experience that transcends race and gender based boundaries but is geared towards

progressive political action. My engagement with this worldly political Üstruggle' never deviates far from a

connection with a Maori spiritual world. Accordingly, in this paper I have attempted to emulate, despite my

earthly limitations, that which I see in Hine Titama as the omniscient aroha of a Maori goddess.

I have been discerning in my choice of postcolonial feminist terms. This choice is related to my understanding

of Maori culture, including art, mythology and politics that resonate in a wider, more transnational world beyond

New Zealand's shores. References to the Maori deity Hine-titama permeate this paper. These references have

connections, in some cases obvious and in others implicit, with other examples of Kahukiwa's art. Paintings

such as Hine-Titama evoke notions of the strength, vitality and potential of Maori women. The goddess Hinetitama can also be incorporated into a recognition, based on compassion not self-aggrandisement, of the

negative consequences of an over-simplistic approach to art analysis. With this incorporation in mind, I have

attempted a more complex and rigorous analysis of Robyn Kahukiwa art and the sociopolitical, culturally-based

world she inhabits. There is a necessary and politically progressive intersection between the examples of

feminist thought I have given and Kahukiwa's art and life. Therefore, I conclude that a certain, criticallyassessed, selection of feminist analyses intersect with Kahukiwa and the art and life of some, though not all,

other Maori women artists.

In my survey of postcolonial feminist discourses, I have been particularly inspired by Irihapeti Ramsden's

Ücritical struggle' from Gayatri Spivak's Üshuttling aporetic position'. My personal reading of Kahukiwa's

paintings (Hine-Titama is only one of many examples) also encourages me to contribute responsibly to the need

for rigorous analysis. Mine is a politically-based critical Üstruggle' to extend knowledge about Maori women

artists and the visual and literary representation of Maori women within and beyond the Academy.

References

Alpers, A. (1964) Maori Myths and Tribal Legends, Auckland: Longman Paul.

Awatere, H. (1995) ÜMauri Oho, Mauri Ora'. In K. Irwin & I. Ramsden, (eds.) Toi Wahine: The Worlds of

Maori Women, Auckland: Penguin, 31-38.

Bhabha, H. K. (1994) The Location of Culture, London: Routledge.

Baughen, H. (1982) ÜArt Gallery gets Important Painting', The Tribune (Palmerston North, N.Z) 11 July, p. 5.

Best, E. (1952) The Maori as He Was: A Brief Account of Maori Life as it was in pre-European Days,

Wellington, N.Z: R. E. Owen, Government Printer.

Diamond, J. (1998) Takarangi: A Spiral Design on a Patchwork Quilt, B.A. Honours Thesis, University of

Western Australia.

Harasym, S. (ed.) (1990) Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, The Post-colonial Critic: Interviews, Strategies,

Dialogues, New York: Routledge.

hooks, b. (1994) Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations, New York & London: Routledge.

Irwin, K. (1995) ÜIntroduction: Te Ihi, Te Wehi, Te Mana o nga Wahine Maori'. In K. Irwin & I. Ramsden (eds.)

Toi Wahine: The Worlds of Maori Women, Auckland: Penguin, 9-13.

Kahukiwa, R. & P. Grace (1991) Wahine Toa: Women of Maori Myth, Auckland, N.Z: Viking Pacific.

Kawharu, I. H. (1975) ÜIntroduction'. In I. H. Kawharu (ed.) Conflict and Compromise, Wellington, N.Z: A.H &

A.W. Reed, 3-24.

Kirby, V. (1993) ÜFeminisms, Reading, Postmodernisms: Rethinking Complicity'. In S. Gunew & A. Yeatman

(eds.) Feminism and the Politics of Difference, Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 20-34.

Kirker, A. (1995) ÜAn Artist of Social Commitment'. In Bowen Galleries, (eds.) Toi Ata: Robyn Kahukiwa,

Works from 1985-1995, Wellington, N.Z: Bowen Galleries & Arts Council of New Zealand (Toi Aotearoa), 3-6.

Larner, W. & P. Spoonley (1995) ÜPostcolonial Politics in Aotearoa/New Zealand'. In D. Stasiulus & N.

Yuval-Davis (eds) Unsettling Settler Societies: Articulations of Gender, Race, Ethnicity and Class, London:

Sage, 39-64.

Mane-Wheoki, J. (1995) ÜRobyn Kahukiwa: My Ancestors are with Me Always'. In Bowen Galleries (eds.) Toi

Ata: Robyn Kahukiwa. Works from 1985-1995, Wellington, N.Z: Bowen Galleries & Arts Council of New

Zealand (Toi Aotearoa), 9-13.

Marsden, M. (1975) ÜGod, Man and Universe: A Maori View'. In M. King (ed.) Te Ao Hurihuri: The World

Moves On, Aspects of Maoritanga, Wellington, N.Z: Hicks Smith & Sons Ltd, 191-219.

Menehira, H. (1982) ÜTouring Exhibition by NZ Women Artists', Wanganui Chronicle, 4 September, p. 2.

Metge, J. (1976) The Maoris of New Zealand: Rautahi, London: Routledge & Keegan Paul.

Pihama, L. (1994) ÜAre Films Dangerous? A Maori Woman's Perspective on The Piano', Hecate: An

Interdisciplinary Journal of Women's Liberation XX(ii), 239-242.

Ramsden, I. (1995) ÜOwn the Past and Create the Future'. In K. Irwin & I.

Ramsden (eds.) Toi Wahine: The Worlds of Maori Women, Auckland: Penguin, 109-115.

Spivak, G. C. & N. Papastergiadis (1991) ÜIdentity and Alterity: An Interview', Arena 97, 65-76.

Spivak, G. C. & E. Rooney (1994) ÜIn a Word: Interview'. In N. Shor & E.

Weed (eds.) The Essential Difference., Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 151-184.

Te Awekotuku, N. (1991) ÜEntering: into another World', Dominion Sunday Times, 12 May, p. 22.

Te Rangi Hiroa (Buck, Sir P) (1987) The Coming of the Maori, Wellington:

Whitcoulls.

Trinh, T. M. (1989) Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism, Bloomington & Indianapolis:

Indiana University Press.

Jo Diamond, Centre for Cross Cultural Research/Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, Australian

National University. E-mail:jo.diamond@anu.edu.au

6. Magazine & Journal Articles Massad, Joseph The politics of desire in the writings of Ahdaf

Soueif.(novelist) Journal of Palestine Studies v28, n4 (Summer, 1999):74 (1 pages).

Abstract: This review of the works of novelist Ahdaf Soueif explores the major aesthetic and political themes of

her novels and short stories. Soueif's honesty in exploring questions of sexual desire, intercultural dialogue, and

the politics of language are further examined in the accompanying interview.

COPYRIGHT 1999 Institute for Palestine Studies. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner.

In contrast to Arab novelists writing in French (Etel Adnan, Tahar ben Jalloun, Assia Djebar, Abd el-Kabir

Khatibi, Kateb Yacine, inter alia), only a few Arabs have written poetry or novels in English, and fewer still have

made names for themselves in the English-speaking world. This short list was inaugurated by the Lebanese

Jibran Khalil Jibran, whose success in gaining recognition in the West and in the Arab world was

unprecedented. Few since have approached this achievement. Palestinian writer Jabra Ibrahim Jabra's

Hunters in a Narrow Street, Egyptian writer Waguih Ghali's Beer in the Snooker Club, or Palestinian writer

Fawaz Turki's The Disinherited are some such attempts, although Ghali's novel stands in a class of its own.

But a new name has suddenly emerged on the scene: Ahdaf Soueif. Although she received rave reviews for

her first collection of short stories, Aisha, published in 1983, it was Soueif's first novel In the Eye of the Sun,

published in 1992, that launched this talented writer onto the international scene. Critical acclaim poured in from

every corner of the English-and Arabic-speaking worlds, reigniting interest in Aisha. Soueif followed with a

second book of short stories in 1996 called Sandpiper and the same year published a collection of short stories

translated into Arabic under the title Zinat al-Hayah. Both books received more acclaim, with Zinat al-Hayah

winning a 1996 award. Soueif's second novel, The Map of Love, to be published in Britain in June (by

Bloomsbury), is her fourth book and second novel to date. Aside from Arabic, her work has been translated into

Dutch, French, German, and Italian. Soueif is perhaps the first Arab writer of English fiction since Jibran to

achieve such recognition.

Soueif's writings investigate the possibilities of cultural dialogue as well as the politics of desire, both within and

outside this dialogue. Desire, in Soueif's work, always exists in a context of politics, history, and geography, all

of which are intermeshed and cannot be disentangled. She works through this intricate web, tirelessly

portraying the difficulty and ease of negotiating desire on such dangerous terrain. Central to her investigations

is the encounter of East and West, of Arabic and English, and of men and women in an intercultural context.

Soueif explores the lives of middle class and poor Egyptian women (Muslim, Christian, Arab, and Greek), as

well as the lives of foreign expatriates, American, Canadian, English, Turkish, black, white. These characters

and their psychologies emerge as the effects of all that surrounds them - culture, domestic and international

politics, economics, society, family, and above all desire and love. Everything about them is overdetermined in

intricate and simple ways and rendered in a prose of high aesthetic quality.

Soueif identifies strongly with her characters. The heroine of her first collection, Aisha, shares with Soueif the

first letter of her first name (as it is spelled in English), as do her subsequent heroines, Asya al-'Ulama in In the

Eye of the Sun and Sandpiper and Amal in The Map of Love, giving these characters an autobiographical bent.

Soueif's aim is to cut through the confusion and stereotypes of society; the dissimulation of international,

national, and family politics; and the secure matrix through which life and its desires are defined. The journey of

her characters is not one where liberation is the necessary telos, but rather the complex process through which

the unfolding of desire(s) - sexual, social, economic, and political - is shaped by the characters themselves and

all that surrounds them. It is this complicated picture that is painted by Ahdaf Soueif's meticulous brush.

THE BILDUNGSROMAN

In the Eye of the Sun is a coming of age novel in the European Romantic tradition of the bildungsroman. Its

cultural referents, however, are always varied and multilayered. Although the title of the novel comes from a

Kipling poem, the Arab reader of this novel cannot miss its resonance with the famous 1960s song of Egyptian

singer Shadia: "Tell the eye of the sun not to get too hot, for my heart's beloved sets out in the morning."

Although Soueif cites many songs in her novel, she never cites this one, letting it linger in the cultural

preconscious of its Arab reader.

This is both an English and an Arabic novel in ways that are truly fascinating. Soueif transforms English into

Arabic and Arabic into English in revolutionary ways. This is not limited to her rendering of Arabic phrases into

English without any syntactic compromises ("God gives earrings to those without ears," "He is like a grain of salt

which dissolved," "Long live he who sees you," etc.), but also in the very narrative structure of the novel, in its

very affect. English is reworked by Soueif to tell the story of Asya al-'Ulama, a young Egyptian girl who visits

Britain as a child, grows up in Cairo where she finishes high school and college, marries her sweetheart, and

then moves alone to England to pursue her doctorate in linguistics (though he joins her later for a brief stay).

Her journey to England - like the many Arabs before her whose fictionalized journeys were registered in novels

like al-Tayyib Salih's Mawsim al-Hijra Ila al-Shamal, Tawfiq al-Hakim's 'Usfur min al-Sharq, Yahya Haqqi's Qindil

Umm Hashim, Baha' Tahir's Bi al-Amsi Halimtu Bika - frames a number of developments, including her

continued pursuit of self-actualization, the use of Egypt as a referent and measure by which England is

evaluated, and her ongoing exploration of emotional and sexual desires. Several of these developments had

already been present during Asya's Cairo period. England, however, was a time and a place in her life that

gave a new context that shaped them. This is not the first time that Soueif transports an Egyptian girl or woman

to the heart of Empire. In Aisha, we witness the journey of a teenage Aisha to England, a strange and exotic

place, where she cannot seem to fit in. Unlike much of the Arabic literary genre within which she is writing,

Soueif sends her female, not male, characters to Europe.

It is Asya al-'Ulama who explores the meanings of home and exile through interweaving the personal and the

social and the political and the sexual.

England is not reduced to the imperial center that it was, although its imperial role is never ignored. The British

Empire was " b uilt of course on Egyptian cotton and debt, on the wealth of India, on the sugar of the West

Indies, on centuries of adventure and exploitation ending in the division of the Arab world and the creation of the

state of Israel etc. etc. etc." (pp. 511-12).

The motor of this story is Asya's quest to combine love and desire. When she met Saif as a teenager, she

experienced both. As her parents insisted that she could not marry Saif until she finished college, and as Saif

refused to consummate their sexual desires before the marriage despite Asya's insistent requests, Asya longed

for the marriage that would finally consummate her love and desire for Saif. But, the moment their romance had

social sanction through the official engagement, it ceased to be the organizing principle of the relationship.

When the wedding night arrived, the moment of consummation failed. In naming her leading male character

"Saif," which is related to "Soueif," Soueif is identifying (and affiliating) with him. There is, however, an

ambivalence about this identification. Perhaps, it is here that the autobiographical element is strongest, as

Soueif's ambivalent identification with Saif coupled with Asya's inability to consummate her relationship with him

might be the effect of an unconscious incest taboo at work. For Asya, however, the failure to consummate the

relationship was to function as an indefinite deferment of the combining of love and desire. From then on, Asya

could only have one or the other, never both.

DESIRE AND CULTURE

Asya's journey of learning teaches her the difference between love and desire. When she finally consummates

her sexual desire with Gerald Stone, an overbearing uncouth English hippie (who is the antithesis of the

debonair, sophisticated, and cosmopolitan Saif) she realizes that only desire, not love, was involved. She is

also attuned to how race and sex are intertwined in the West. She questions Gerald:

"Why have all your girl-friends been from 'developing' countries?"

"What?"

"You've never had a white girl-friend, why?"

"I don't think that way, man."

"Yes you do - and the reason you've gone to Trinidad - Vietnam - Egypt - is so you can feel superior. You can

be the big white boss - you are a sexual imperialist -"

"You don't even believe what you're saying," Gerald laughs.

"Yes I do. You pretend - to yourself as well - that it's because you don't notice race - or it's because these

cultures retain some spiritual quality lost to the West - you pride yourself that you dance 'like a black man' - but

that's all just phoney - " (p. 723)

There she was, hopelessly in love with her husband Saif, who would not, could not sleep with her, while being

utterly desirous of the unlovable Gerald. Asya finally rids herself of both, gets her Ph.D., and returns home to

Cairo, love and desire remaining separate and ununifiable.

In the Eye of the Sun is far more than Asya's emotional journey. Soueif meticulously documents not only Asya's

emotional life but also that of the Arab world. In the Eye of the Sun takes us from the devastating defeat of the

Arabs in the 1967 War and the shock of Nasir's sudden death to the massacres of Palestinians in Jordan,

Sadat's new era, the bread riots of 1977, the Lebanese Civil War, and the Washington Post's list of foreign

leaders on the CIA payroll. She is also a chronicler of cultural politics. We listen to Umm Kulthum's "al-Atlal"

and its political overtones and read the incomparable explication of al-Shaykh Imam's "Sharraft Ya Nixon Baba"

as an instance of the (im)possibility of a certain type of cultural dialogue. We listen to Western pop and rock.

Even film actors such as Mahmud Mursi and Ahmad Mazhar make an appearance, as do directors and films,

including Pasolini, Fellini, and Rossellini's Roma, Citta Aperta. The reader is also subjected to a litany of

technical aspects of Asya's linguistics dissertation. These are not simple props that carry the narrative, they are

all integral to Asya's emotional journey of learning and knowledge.

Edward Said has described Soueif as "one of the most extraordinary chroniclers of sexual politics now writing."

That she indeed is. Soueif explores desire not as a Western binary of hetero- and homosexual desire, but

rather as a fluid set of possibilities existing on a continuum. It is this that allows her to describe in a short story,

"Her Man" (in Aisha), how two poor Egyptian women (co-wives) can experience sexual pleasure together as well

as with men, albeit as a ruse so that one of them can get her man by having him divorce the other. In "The

Apprentice" (in Aisha), where Soueif registers her major reference to male homosexual desire, she seems less

comfortable, as she registers it only as aggression. A young poor boy, Yosri, newly employed at a ladies' hair

salon, Salon Romance, begins to explore his desire for his female customers through a series of sensual

encounters with their hair, heads, and ears. His sensuality is reflected sartorially, through his donning white

denims, a dark blue shirt, unbuttoned half way, and a gold chain with a Pisces pendant on his chest. In his new

attire, Yosri arouses the desire of a manly mechanic who seems intent on having his way with the young

feminized

apprentice (the mechanic was the realization of some mythical pirates of whom the women at the salon had

spoken: "Maybe they worked both ways. Took what they could find. Sometimes a boy, sometimes a

woman..."). The encounter is announced at the end of the short story, but unlike female homosexual desire in

"Her Man," male homosexual desire is not explored as pleasure. The only other time that mention is made of

male homosexual acts is in the context of defeat, when an angry and humiliated Saif tells Asya, after she

informs him about her affair with Gerald Stone in ln the Eye of the Sun, "You can invite him back and he can

fuck me too" (p. 633).

Soueif also explores incestuous desire sensitively in "The Water Heater" (in Sandpiper). A young God-fearing

law student named Salah averts his eyes on the street from women lest he be tempted by sinful desires. His

sexual self-discipline, however, erupts in an uncontrollable and incessant desire for his younger sister Faten.

So as not to compromise himself, he sacrifices his sister, making her pay for his sinful thoughts by marrying her

off to a cousin, sabotaging her plans to continue her university education.

In tracking these inter-and crosscultural rhetorics of desire and discovery, Soueif's literary techniques are varied,

including a sophisticated use of stream of consciousness. She uses letters, diaries, flashbacks, and political

communiques to contextualize, layer, and interrupt the narrative, creating prose of shimmering complexity.

Soueif is unwilling to close the book (literally) on her major characters or on important episodes in their lives.

There is always something that exceeds the characters and that Soueif still wants to explore. This is evident in

the reappearance of a number of incidents and characters from (and within) Aisha in In the Eye of the Sun.

Asya al-'Ulama herself, as well as other characters from In the Eye of the Sun, spill over beyond the perimeter of

that novel and into a number of short stories in Sandpiper and in Soueif's upcoming novel The Map of Love. In

these reincarnations, the reader is introduced to other aspects of these characters' lives, to different angles from

which to view certain of their experiences, or to more detail in narrating the same experiences. Time here is not

necessarily chronological. In Sandpiper, for example, Asya and episodes of her life are reexamined from a time

period that precedes the moment at which In the Eye of the Sun ends.

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

Soueif's temporal organization of her novels adds to both the bildungsroman aspects of her novels and to her

implicit discussion of the possibilities and pitfalls of crosscultural dialogue. In the Eye of the Sun begins in

medias res in July 1979 and goes back to May 1967, only to proceed chronologically again to April 1980. In

doing so, Soueif is telling a story that is still happening. This is quite different from the way she sets up a

dialogic of past-present juxtapositions in The Map of Love. The Map of Love begins with the present (1997) and

then transports the reader into a series of back-and-forth temporal peregrinations between the last fin de siecle

and the current one.

This playing with various time frames to organize narrative allows Soueif to explore another of her central

concerns more effectively, namely, geographic dislocation. If In the Eye of the Sun and Aisha took Arab women

and girls to the heart of Empire, Sandpiper and The Map of Love transport European and North American

women to the colonies. The Map of Love transports Anna Winterbourne, an English woman, at the last fin de

siecle from London to Cairo, and Isabel Perkman, an American woman, at the current fin de siecle from New

York to Cairo and back. Moreover, it transports the Egyptian-Palestinian Amal from London to Cairo and then

from Cairo to Tawasi in Upper Egypt, and takes Amal's brother 'Omar from New York to Palestine and Cairo and

back to New York.

In "Melody" (in Sandpiper), we are transported to a Gulf Arab country where a middle-class Canadian woman

(whose husband works there), in an air of superiority, describes her encounter with a middle class Turkish

woman, Ingie (whose husband also works there). Ingie's husband wants her to bear more children. She

pretends to agree but surreptitiously takes contraceptive pills. The Canadian, on the other hand, wants more

children, but her husband had a vasectomy to make sure she does not trick him. What is fascinating about this

short story is the subtlety with which Soueif explores the blindness of the white Canadian to her own experience

of sexist oppression-as she was too busy noticing that of her Turkish counterpart - which is concealed under a

facade of racial/cultural superiority.

The Map of Love ushers in moments of intercultural understanding and dialogue. Soueif, however, is all too

aware of the rarity of such achievements. She understands that the predominant Western journalistic interest in

the Arab world is not aimed at cultural dialogue and understanding, but rather at exoticizing the Arab and

Muslim other through covering topics like "the fundamentalists, the veil, the cold peace, polygamy, women's

status in Islam, female genital mutilation..." (p. 6). Still, the two Western characters in the novel, Anna and

Isabel, who fall in love with Arab men, Sharif Basha al-Baroudi and 'Omar al-Ghamrawi (thus reversing the

gender course that desire took in In the Eye of the Sun, where it was an Arab woman who desired an

Englishman), are fully capable of understanding the other. Their understanding is not necessarily based on the

obliteration of radical alterity and the transformation of the other into an approximation of the self (as is the case

with many Western do-gooders); rather, it is based on understanding the other on the other's own terms.

The Map of Love does not have the same autobiographical bent of Soueif's other writings. This is a fictional

love story that evolves within the context of real historical events. It begins at a moment when the British

Empire was an Empire and ends with the indefinite and unchecked growth of the American Empire and its

current "globalization." The old colonial order, when the British roamed the country freely, is compared with the

present neocolonial globalized one: "It must be hard to come to a country so different, a people so different, to

take control and insist that everything be done your way. To believe that everything can only be done your

way.... I read the memoirs and the accounts of these long-gone Englishmen, and I think of the officials of the

American embassy and agencies today, driving through Cairo in their locked limousines with the smoked-glass

windows, opening their doors only when they are safe inside their Marine-guarded compounds" (p. 70). One

wonders if the American limousines and their smoked-glass windows are the veil that Americans must wear in

public spaces inhabited by dangerous, yet seductive, locals!

BRIDGING CULTURES

The Map of Love is a love story about an English aristocratic widow (Anna Winterbourne) who decides to travel

the empire and a middle-aged aristocratic Egyptian bachelor (Sharif Basha al-Baroudi). Anna, already

influenced by her English father-in-law's opposition to imperial expansion and racism (in the context of the Boer

War), is receptive to liberal ideas of anticolonial nationalism. Her friendship with Sharif's sister, Layla, is one of

the main bridges of cultural dialogue in the novel. Almost a century later, Isabel, the young New Yorker (who is

the great granddaughter of Anna and Sharif), falls in love with 'Omar al-Ghamrawi, a renowned New York-based

Egyptian-Palestinian musician. Her friendship with Areal ('Omar's sister) parallels that of Anna and Layla as a

contemporary cultural bridge. An important element that Soueif uses to effect a cultural dialogue is her creative

use of etymology in explaining Arabic words, which constitutes one of the many delicate pleasures that the

novel offers the reader. Here is Areal teaching Isabel Arabic:

"Qalb: the heart, the heart that beats, the heart at the heart of things.

Yes?"

She nods, looking intently at the marks on the paper.

"Then there's a set number of forms - a template almost - that any root can take. So in the case of 'qalb' you get

'qalab: to overturn, overthrow, turn upside down, make into the opposite; hence 'maqlab': a dirty trick, a turning

of the tables and also a rubbish dump. 'Maqloub': upside-down; 'mutaqallib':

changeable, and 'inqilab': coup...."

So at the heart of things is the germ of their overthrow; the closer you are to the heart, the closer to the reversal.

Nowhere to go but down. You reach the core and then you're blown away - (p. 82)

The novel is a sort of investigative story. Isabel finds an old trunk in her dying mother's belongings containing

mounds of paper written in Arabic and English. It is said that the trunk had traveled at the end of the previous

century from London to Cairo and back and then to New York. Isabel, an American journalist on assignment in

Egypt (1997/1998) writing an article on the millennium and Egyptian youth, brings the trunk with her so that

Amal can help her unravel its mysteries. It turns out that the trunk belonged to Isabel's great-grandmother,

Anna, and contains her journal entries, letters, and other papers as well as Layla al-Baroudi's letters and

writings. As the story is unraveled, we live, through these letters and memoirs, the love story of Anna and

Sharif, whose love persevered against many odds - the ostracism to which Anna was subjected by the English

colons in Cairo on account of her marrying an Egyptian and the questions raised about Sharif's nationalism by

Egyptian nationalists on account of his marrying a colonizer. This love story is paralleled by the more

complicated and fragmented love story between 'Omar al-Ghamrawi and Isabel. On the sidelines of these two

love stories is Amal, the investigator and unraveler. Whereas Anna and Sharif's love ends in tragedy in the

context of colonialism and anticolonial nationalism, the novel ends with Amal's hallucinatory apprehension that a

similar fate might be awaiting her brother and Isabel in our neocolonial globalized context.

Aside from the letters and memoirs, Soueif uses her skill as a writer to narrate certain sections in a way

reminiscent of both a traditional hakawati (Arab storyteller) style and that of Trollope, Dickens, and especially

Thackeray's Vanity Fair: "And so it is that our three heroines - as is only fitting in a story born of travel, unfolded

and shaken out of a trunk - set off upon their different journeys. Anna Winterbourne heads eastward out of

Cairo, bound for Sinai in the company of Sharif al-Baroudi. Amal al-Ghamrawi and Isabel Perkman take the

Upper Egypt road which will lead them to Tawasi, in the Governorate of Minya" (p. 164).

Whereas history and politics were almost hors de texte in In the Eye of the Sun, they are au fond du texte in The

Map of Love. As the fictional and the real are intermingled in terms of family relations and historical events, the

fictional characters become real historical figures that could very well have existed. The Baroudis, although

fictional characters, belong to a real family. Their paternal uncle Mahmoud Sami Basha al-Baroudi, in addition to

being an important poet, is one of the Egyptian heroes of the 'Urabi revolt. Other fictional characters belong to

the real Palestinian family of Khalidi.

Although politics sometimes overpower the narrative of The Map of Love, this perhaps was unavoidable in

maintaining the integrity of the text. Yet this beautiful and at times surreal novel, too, explores the politics of

desire and love.

The amount of historical research that Soueif must have undertaken to produce this novel is truly monumental.

She has familiarized herself with minute details about a period of Egyptian history (Autumn 1897-December

1913) that is not particularly well studied (except for the infamous shootings at Denshwai), as it is bracketed

between two revolutions - the 'Urabi revolt of 1882 and the 1919 revolution - to which it is subordinated. The

Mashriqi and Palestinian histories of the period are also meticulously revisited. From the beginning of the

Zionist colonial project to the apex of Arab anti-Ottomanism, Soueif transforms history into a guide to the

present. She renders historical actors real by giving them a tangible human dimension. Characters that play a

role or make an appearance include Shukri al-'Asali, Rashid Rida, Yusuf al-Khalidi, Theodor Herzl, Rabbi Zadok

Kahn, Cattaoui Pasha, and Shaykh Muhammad 'Abduh. Even a number of current characters are either real or

based on real people. 'Omar al-Ghamrawi, for example, is a fictionalized character loosely based on Palestinian

intellectual Edward Said.

The depth of Soueif's historical research, her enlivening the history she traverses in the novel, as well as her

concern with negotiating the problem of difference across the boundaries of culture, are evident in her

remarkable attention to clothes. Whereas her fastidious descriptions of clothes provide the reader with a tactile

feel for the characters, they also play another crucial role. As in "The Apprentice," where sartorial change

produced an epistemological change for Yosri, gender and cultural crossdressing in The Map of Love (Anna

wears the clothes of Western men as well as that of Arab women and men in order to travel incognito) signal a

complete epistemological break. When Anna dresses as an Egyptian Muslim woman in public, not only are her

looks transformed but so are her perceptions as well as those of others toward her. Thus disguised, she sees a

number of English aristocrats pass her by unawares at Cairo's train station: "but the oddest thing of all was that I

suddenly saw them as bright, exotic creatures, walking in a kind of magical space, oblivious to all around them;

at ease, chattering to each other as though they were out for a stroll in the park, while the people, pushed aside,

watched and waited for them to pass" (pp. 194-95). It is experiences like this one that helped Anna maintain

her culture and identity and understand - not appropriate as many do - that of the Oriental other. French, not

English or Arabic, is the medium of communication between Sharif and Anna (who was being taught Arabic by

Layla). French, it would seem was the most "neutral" of available languages for both.

Soueif's talent has been praised by a large number of Arab and Western literary figures and scholars. These

include Leila Ahmad, Radwa 'Ashur, Victoria Glendinning, Sun'allah Ibrahim, Frank Kermode, Hilary Kilpatrick,

Penelope Lively, Hilary Mantel, and Edward Said and Gabir 'Asfur. Soueif is a product of a middle-class

quintessentially Cairene intellectual milieu. Her mother, Fatmah Musa, is a well-known professor of English

literature at Cairo University, and her father, Mustafa Soueif, a professor of psychology at Cairo University who

used Ahdaf, when she was a child, as a case study in his dissertation. When she was born in 1950, they named

her "Ahdaf" to express their commitments to the aims and goals of the revolution to come. Soueif's interest in

language and psychology are perhaps the direct effect of her lineage. In In the Eye of the Sun, Soueif writes

that a "middle-aged spinster from Manchester came out to Cairo in the Thirties to teach English. A small untidy

12-year-old girl fell in love with her and lived and breathed English literature from that day on. That girl was my

mother." This may be so, but Soueif's feel for and understanding of language - any language - derive from a rare

intellect that is entirely Soueif's own achievement.

On a recent visit to Washington to read parts of her forthcoming The Map of Love at the Kennedy Center, Ahdaf

Soueif and I sat on 9 May at a sidewalk cafe for an interview.

JM: Your writing has a strong political inflection that varies in style depending on the novel. Macropolitics play

very important yet different roles in In the Eye of the Sun and in The Map of Love. What accounts for this

difference?

AS: Well, In the Eye of the Sun really started out as the story of Asya al-'Ulama and then the story of the family

and friends surrounding her. It was not possible to do that without the history and politics, but the impulse that

generated the novel was interest in this character and in her immediate circle. I think that it can be described as

a classical novel of education, as it were, of growing up. History and politics come into it only insofar as they

affect our protagonist and those around her: Chrissie's fiance lost in the Sinai in 1967 or Bassam being thrown

out of Egypt at the time of Camp David.

The impulse behind The Map of Love was different. It was more overtly historical and political, to do with

crosscultural relationships, with history, with the relationship of the Western world to Egypt and to our area. So,

there, the history and the politics are much more in the forefront, much more central to the novel and the plot.

Part of what The Map of Love is about is how much room personal relationships have in a context of politics and

history. And so history and politics are as much players as the characters maybe even more so.

JM: Stylistically, it seems to me that although politics are intermingled in the narrative of In the Eye of the Sun,

they also interrupt it to announce political events that seem external to the narrative yet provide background.

As you said, in The Map of Love, politics are very much part of the structure.

Is the difference between the two the difference between a bildungsroman and a historical novel?

AS: I'm a bit wary of the term "historical novel." But I think that the difference also reflects my preoccupations at

different stages of my life. In the bildungsroman, in Asya al-'Ulama's life, there is a large event, which is the

1967 War. She is also a child of the revolution and is shaped by it, but these are not the central problems of her

life. Her awareness, her consciousness is much more about her personal predicament, what she's going to do

with her life. I think that at the end of the book, her vision broadens to include a lot of things other than herself,

to see herself as part of all that she has come home to. In that sense, the politics in the novel do interrupt the

flow. I used to think that maybe I, as the writer, had not found the ideal way of merging the political information

necessary for this book into the narrative. That the method I chose - of cutting to documentary, as it were - was

not ideal. Now, I wonder if it would have been possible to do it any other way. How do you integrate something

that is, in a sense, extraneous to the inner life of your characters? There is a scene during the 1967 War, where

Asya goes down into the streets, and there the events are integrated. But on the whole, as a large event, it isn't,

because it did not directly impinge on her life at that point. In The Map of Love, it's quite different. The politics

are there from the beginning, and possibly that's because I now see politics and history as central to our lives,

and therefore I created a situation and characters to whom politics and history are central. Also, politics and