The task ahead involves growing civil society in

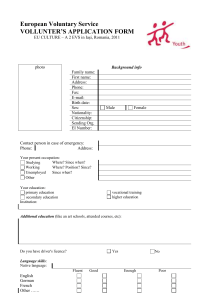

advertisement

GROWING CIVIL SOCIETY IN NORTHERN IRELAND Jon Van Til The task ahead involves growing civil society in Northern Ireland. Social systems, like gardens, are grown intentionally. We talk about growing a garden. We talk about growing families. And a recent American President much beloved in Northern Ireland, Bill Clinton, used to talk a lot about the importance of growing the economy. All these ideas share a common characteristic: They have to do with intentional acts aimed at making something good bigger and better. The gardener wants to grow food that is tasty, nutritious, and bountiful. The parent wants a family composed of children who are happy, healthy, and able to take on the world. The president wants an economic order that is productive and expanding in its size. And so it is with civil society. The reason we want to “grow” it, to see it develop and flourish, is that we are interested in what it will provide for us—both as individuals and as a society. Civil society is important, that is to say, if it helps produce what the American founders identified as a “more perfect union”. Now what precisely is meant by civil society? How might we recognize it if we actually came across it? The more I have worked with the idea, as for instance in a recent book titled Growing Civil Society (Van Til, 2000), the more I have come to find it invaluable in understanding not only what citizens can do to make society work, but how we can come to understand the structure of the good society. A civil society, after all, is one in which the lives of its individual residents and citizens are enriched by the right workings of the major institutions and organizations of that society. Studies and experience in many nations indicate that civil society works best where citizens have learned the lessons of communitarianism, where the organizations of their communities have learned to partner with others, and where they are not afraid to take risks toward the improvement of the life of their neighborhoods, town, region, country and world. The lessons of communitarianism? As sociologist Amitai Etzioni (1993) has shown clearly, both rights and responsibilities are important in the modern world, and need to be balanced with each other. Too much focus on rights and not enough on responsibilities leads to contention and endless dispute. Too much focus on responsibilities and not enough on rights leads to paternalism and apathy. A leading spokesperson of this view is British Prime Minister Tony Blair, with his ideas of the “third way”. Partnership? In the modern organizational world, where even in a small city there may be thousands of differing organizations of all stripes, it is critical to build bridges among and between groups of varying sorts. Often the most successful communities are those which have the capacity of linking with a wide range of organizations in other communities, city-wide, and nationally as well. Risk-taking? The literature on community development and voluntary action is full of the concept of social entrepreneurship, which really means organizing risk in response to the meeting of a social need.i Social enterprises, it is asserted, may be more capable than traditional voluntary efforts to sustain their work in a time of increasing privatization and declining levels of statutory or governmental support. They may also be more attentive to the needs for expanding employment and meeting a variety of economic needs within communities in a cooperative structure and process. I had begun in my own work, particularly in a book published in 1988 and titled Mapping The Third Sector, to look at society as composed of four basic institutions: the economy, government, the third sector, and the "informal sector"--the last being the home of family, kin, and neighborhood, what I identified above as “crucibles of identity”. A good society resembles a sturdy vehicle, firing on all four of its cylinders. I'll hold to that position even now. Contemporary society provides us with four major sets of institutions to solve our common problems: families and other crucibles of identity like churches and schools that represent "core culture", voluntary organizations and other nonprofit organizations that bring people together to address common problems, governmental structures that embody democratic aspirations and institutions, and a myriad of corporations and businesses that build common wealth and foster employment. I developed a somewhat flaky way of remembering these four institutions, which I called the "PECTS" schema: P for Politics, E for Economics, C for core Culture (the family, kin, neighborhood, and much of education and religion), and TS for the third sector. Out of that schema comes a formula for building a good society, or, if one prefers, growing civil society: Solutions will come when it becomes widely recognized that both tradition and change are important, that both freedom and order must be secured. This will only happen when the contributions of each major sector of society are recognized: when cultural values sustain family, religious, and community life; when Third Sector (voluntary, community) organizations organize both collective action and service freely and effectively; when business organizations discover and serve the humanity of their employees as well as their consumers; and when government assures a level field of opportunity and a fairness of result in policy, economic reward, and individual expression (Van Til, 2000:, p. 79). For an excellent study of community enterprise in Derry, see Denise Crossan, Towards a Classification Framework for Non-Profit Organizations, doctoral dissertation submitted to the University of Ulster, 2007. i