Legal Aspects in Education - Jamie

advertisement

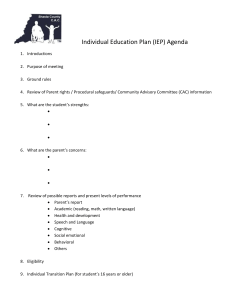

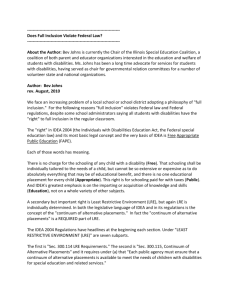

Legal Aspects in Education Integration of Special Education Students Position Paper Jamie Stearns August 5, 2008 Dr. Rose Special Education students should be afforded the right to learn in a continuum of placements and these opportunities should not come at the expense of other students. This can be called mainstreaming or inclusion, but ultimately the issue of how a student is educated, when that student will be educated and where they will be educated is part of a special education students rights under The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). IDEA affords children with special needs a Free and Appropriate Education (FAPE) in the Least Restrict Environment (LRE). Parents and school districts often go to court to resolve disagreements regarding a FAPE in the LRE. Parents seek reimbursement of private schools when the parent has removed their child because they feel their child’s rights to a FAPE have been violated. Districts and parents seek the courts to resolve issues related to student placement in the LRE. Parents often argue that the school district does not provide a LRE or the services are not appropriate for the student. FAPE means that every child with a special need has the right to a public education that appropriately meets their needs. There is much dispute over the definition of appropriate. The word appropriate is very tricky to define because each student with a special need is unique and requires various services in various locations and for various durations of time. In Board of Education of the Hendrick Hudson Central School District v. Rowley the courts addressed the word “appropriate” in a FAPE. Justice Rehnquist wrote that a FAPE is satisfied “by providing personalized instruction with sufficient support services to permit the child to benefit educationally from the instruction.” This is a landmark decision by the Supreme Court because it means that school districts must provide educational opportunities to students with special needs but these opportunities do not have to be the best of the best. -1- The Supreme Court’s decision in the Rowley case reversed the District Court ruling of the same case. The District Court defined a FAPE as “an opportunity to achieve full potential commensurate with the opportunity provided to other children,” Board of Education of the Hendrick Hudson Central School District v. Rowley 458 U.S. 176 (1982). The District Court’s ruling meant that school districts would have had to provide students with special needs all the possible supports to ensure that their achievement and potential matched. If there is a service the district could provide to improve the education of a student with special needs the district must provide it. Examples of services a district must provide a student for educational purposes are: speech therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and nursing services, to name a few. This component of the law allows that a variety of teachers, therapists and peers will work with a student with special needs with no cost to the parent. Although appropriate does not address the exact location of these services. It is important to note that each student with special needs should have the opportunity to a continuum of placements. The continuum of placements should include “regular and special classes and special schools and institutions” (Longuil, 1994). Appropriate also has implications for a continuum of services; this is linked very closely to LRE. A continuum of services does not mean that all special education students should be educated in a regular education classroom all of the time, better known as full inclusion. In fact, “full inclusion does not appear anywhere in the IDEA and universal full inclusion of all children with disabilities would violate the mandates of the IDEA.” (La Morte, p. 342). -2- In Section 1412 of the IDEA children with disabilities are to be placed “[t]o the maximum extent appropriate . . . are educated with children who are not disabled and . . . removal . . . occurs only when the nature or severity of the disability of a child is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily.” 20 U.S.C. S 1412 (2004). A school district can provide a FAPE without providing LRE and visa versa. If a school district is not able to provide a LRE to a student due to lack of a continuum of placements, the district must pay for the student attend an alternative placement. T.R. is the parent of N.R. a minor who was to attend Kingwood Township. N.R.’s parents were presented with two different Individual Education Plans (IEP) for N.R. The first would have placed N.R. in a regular education kindergarten classroom for full days, N.R.’s parents rejected the IEP. The second IEP placed N.R. in mornings in a preschool with half children with special needs and half the class without special needs. In the afternoon N.R. would go to a resource classroom where he would receive speech therapy and other services. Again N.R.’s parents rejected the IEP. N.R.’s parents then decided to place N.R. in a private daycare, where N.R. had attended the previous year and made academic progress. The parents disagreed with the placement stating it did not provide a FAPE in a LRE. The Circuit Court agreed with the District court that a FAPE would have been provided for N.R. The Circuit Court did not find that the school district would provide the LRE for N.R. The Circuit Court came up with a two part test for determining the LRE. First, education in the regular education classroom was not successful, even with aids and additional services. Second, a regular education classroom is not within a reasonable commuting distance. As a result of T.R. v. Kingwood Township 3rd Cir. (2000) the court -3- stated “the school district is required to take into account a continuum of possible alternative placement options when formulating an IEP, including [p]lacing children with disabilities in private school programs for nondisabled preschool children.” Many parents have argued in court for their child to receive more instruction in the regular education classroom. It has been argued that because IDEA says the LRE in the regular education classroom is always the LRE for students with special education needs. This is not true, to the contrary “more restrictive placements are appropriate when a less restrictive placement threatens the safety of the disabled child or other students or when a child with a disability is so disruptive in a regular classroom that the education of other students is significantly impaired.” (La Morte, p. 343) In the case of Hartmann v. Loudoun County Board of Education a student with autism named Mark was placed in a first grade regular education classroom after a successful kindergarten experience. Mark’s school district went to great lengths to ensure his success. The school district assigned Mark to a small class with independent students, hired a one on one teaching assistant, trained the teacher and teaching assistant, brought in consultants, and had a special education teacher on the team. Mark did not make academic gains during his first grade year and had a significant level of disruptive behaviors. The district proposed a change of placement for academics for Mark’s second grade year. Mark’s parents refused this plan. The court found that Mark was provided the LRE even when his placement in regular education classes was decreased for academic instruction in a different placement. In providing students with the LRE it is important to take into consideration other students within the regular education setting. In the Hartmann case the court also stated, “The mainstreaming provision represents recognition of the value of having -4- disabled children interact with non-handicapped students. [S]ocial benefits [are] ultimately a goal subordinate to the requirement that disabled children receive educational benefit,” Hartmann v. Loudoun County Board of Education 4th Cir. (1997). Because Mark did not make academic progress in his first grade placement the court determined that Mark’s IEP did not violate LRE. The implications of a FAPE in the LRE is as unique as the population the status serves. FAPE has multiple meaning. In Rowley the definition of appropriate was addressed and defined as providing educational benefit without providing the maximum. In the Hartmann case, Mark Hartmann was not making academic gains in a regular education placement and was highly disruptive to his peers. Mark’s placement was not in a LRE because of his lack of academic progress and disruptive behaviors. The T. R. case brings together FAPE and LRE, the court found that a FAPE was provided for T.R. but the LRE needed to be explored more in depth as T.R. was able to make academic gains in a less restrictive environment than the school district was able to provide. All of these put together support the idea that students with special needs should be provided a FAPE in a LRE. The appropriateness of the education needs to be unique to the student and provide academic growth. The LRE needs to be a continuum of placement options the IEP team assesses to determine what will be in the best interest of the student. -5- Resources Board of Education of the Hendrick Hudson Central School District v. Rowley 458 U.S. 176 (1982) Hartmann v. Loudoun County Board of Education 4th Cir. (1997) Longuil, C. (1994).Free appropriate education: A historical perspective. Journal of Visual Impairment and blindness. v. 88 issue 4, 292-294. Kutash, K (Dec. 2006). Creating Environments that work for all youth: Increasing the use of Evidence-based strategies by special education teachers. Research to Practice Brief, 5(1), Retrieved August 1, 2008. T.R. v Kingwork Township 3rd Cir. (2000) -6-