word order

advertisement

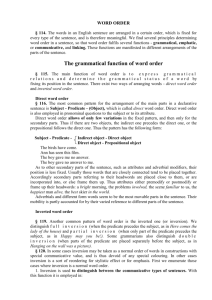

Seminar 10 THE COMPOSITE AND SEMI-COMPOSITE SENTENCE. THE SENTENCE AND THE TEXT Individual tasks: Make reports on the following questions 1. The structure of the composite sentence a. Report 1: Khaimovich, Rogovskaya. P. 278-281 b. Report 2: Ilyish p 318-327 2. The compound sentence, its characteristic features and classification Report 3: Blokh p. 332-340 3. The complex sentence. Different classifications, the problem of parenthesis. Report 4: Khaimovich, Rogovskaya. P. 281-294 Report 5: Blokh p. 303-316 Report 6: Blokh p. 316-328 Report 7: Blokh p. 328(paragraph 9) -332 4. The semi-composite sentence Report 8: Blokh Chapter 29, p. 340-351 Report 9: Blokh Chapter 30 p. 351-361 5. The sentence and the text Report 10 Blokh Chapter 31 Units larger than a sentence. Cumulative and occursive connection of sentences in the text, paragraph 1-2, 5-8. (Make a written report) Report 11 Blokh Chapter 31 Types of cumulation. Par. 3-5. Make a written report) To be done by all the students Questions: 1. What is the main principle of differentiating between the simple sentence and the composite sentence? 2. What are the two main syntactic types of clause connection? 3. What are the differential features of the compound sentence? 4. What semantic relations underlie coordinative clauses? 5. What principles are used for classifying subordinate clauses? 6. What sentence is termed "semi-composite"? 7. What is the nature intermediary syntactic character of the semi-composite sentence? 8. What types of semi-composite sentences are singled out? 10. What are the differential features of the semi-complex sentence? 11. What is peculiar to the semi-compound sentence? 12. What are the differential features of the complex sentence? I. Define the types of clauses constituting the following sentences: a) 1. She was looking for a place where they might lunch, for Ashurst neverlooked for anything (Galsworthy). 2. They were fleeting as one of the glimmering or golden visions one had of the soul in nature, glimpses of its remote and brooding spirit (Galsworthy). 3. Life no doubt had moments with that quality of beauty, of unbidden flying rapture, but the trouble was, they lasted no longer than the span of a cloud's flight over the sun: impossible to keep them with you, as Art caught beauty and held it fast (Galsworthy). 4. But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest (O.Henry). 5. While they were driving he had not been taking notice... (Galsworthy) 6. And a sudden ache beset his heart: he had stumbled on just one of those past moments in his life, whose beauty and rapture he had failed to arrest, whose wings had fluttered away into the unknown... (Galsworthy) 7. "Can you tell us if there's a farm near here where we could stay the night?" (Galsworthy) 8. "It is a pity your leg is hurting you." (Galsworthy) 9. That he was wealthy went without saying, but beyond a few such deductions John knew little of his friend, so it promised rich confectionery for his curiosity when Percy invited him to spend the summer at his home "in the West" (Fitzgerald). b) 1. "A further knowledge of facts is necessary before I would venture to give a final and definite opinion." (Doyle) 2. "Can you ask me, then, whether I am ready to look into any new problem, however trivial it may prove?" (Doyle) 3. "I know it looks as if I've got you here on false pretences but we really ought to be thinking about the possible dates." (James) 4. "I am about to write your cheque, however unwelcome the information which you have gained may be to me." (Doyle) 5. Did it matter where he went, what he did, or when he did it? (Galsworthy) 6. The flying glamour which had clothed the earth all day had not gone now that night had fallen, but only changed into this new form (Galsworthy). 7. "It's I who am not good enough for you." (Galsworthy) And he uttered a groan which made a nursemaid turn and stare (Galsworthy). 8. And he uttered a groan which made a nursemaid turn and stare. (Galsworthy). 9. If he were drowned they would find his clothes (Galsworthy). c) 1. If she was what most American girls were, he was quite confident that this would not be too difficult, although he had once or twice been giggled at by young ladies when they had finally found a moment in which to be alone with him at a party and he had spoken to them tenderly (Saroyan). 2. She could not understand why, instead of smiling at such good news, Miss Elizabeth covered her eyes with her hands and groaned (Forster). 3. There are two very good reasons why she should under no circumstances be his wife (Doyle). 4. On the face of it the case is not a very complex one, though it certainly presents some novel and interesting features (Doyle). 5. jHe did not speak intimately again that night to Laura Slade, for he knew her aunt would send her back to Philadelphia immediately if she knew their secret, but when he came on stage at Monday night's performance and acknowledged the applause that greeted him he saw that she was in the seat he'd had the management put aside for her and he was able quite unobtrusively, as he bowed very low, to look her straight in the eye, and to throw her a kiss, as if to the entire audience (Saroyan). 6. All he wanted to do was help her (Saroyan). 7. She was terrified and she was rapt, as if the sight of the wolves moving over the snow was the spirit of the dead or some other part of the mystery that she knew to lie close to the heart of life, and when they had passed she would not have believed she had seen them if they had not left their tracks in the snow (Cheever). 8. Jud was a monologist by nature, whom destiny, with customary blundering, had set in a profession wherein he was bereaved, for the greater portion of his time, of an audience (O.Henry). 9. I never noticed anything in what she said that sounded particularly de structive to a man's ideas of self-consciousness; but he was set back to an extent you could scarcely imagine (O.Henry). d) 1 . If I drew from a photograph my drawing showed up characteristics and expressions that you couldn't find in the photo, but I guess they were in the original, all right (O.Henry). 2. At that adoring look he felt his nerves quiver, just as if he had seen a moth scorching its wings (Galsworthy). 3. In the bewildering, still, scentless beauty of that moment he almost lost memory of why he had come to the orchard. 4. He was the only son of a late professor of chemistry, but people found a certain lordliness in one who was often so sublimely unconscious of them (Galsworthy). 5. "There's trout there, if you can tickle them." (Galsworthy) 6. It was about the period of the Celtic awakening, and the discovery that there was Celtic blood about this family had excited one who believed that he was a Celt himself (Galsworthy). 7. Salamat, still chatting with Mrs. Boake-Rehan Adams, was about to ask who the young lady was who looked like a Renoir girl and gave one the feeling of having been created out of rose petals and champagne when the girl herself came leaping and laughing through the excited people to her aunt to ask whether she might not stay with her an extra day before going home to Philadelphia (Saroyan). 8. Jud laid down his sixshooter, with which he was preparing to pound an antelope steak, and stood over me in what I felt to be a menacing attitude (O.Henry). 9. He put his hands on the dry, almost warm tree trunk, whose rough mossy surface gave forth a peaty scent at his touch (Galsworthy). 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. II Comment on the word-order in the sentences. Should you meet her there, give her this message, please. What are they giving at the opera tonight? So tired were the hunters that they decided to spend the night on the bank of the stream. He saw Picket inflating a balloon; little was visible of his face or figure behind that rosy circumstance. There was a murmur in the room. “Helen doesn’t know much,” said father. Not till then did they see the disaster in the corridor. For many a time did I sit on the bank of the blue and green lake. How beautiful and sad that was! Here is another plate for the nursery children. “Where’s Sally?” – “Here I am, mother.” There has always been piece in the planet. It was the government who was responsible for the strike. I never saw him so depressed – neither did I. Had you come earlier you would have found him at home. WORD ORDER § 114. The words in an English sentence are arranged in a certain order, which is fixed for every type of the sentence, and is therefore meaningful. We find several principles determining word order in a sentence, so that word order fulfils several functions - grammatical, emphatic, or communicative, and linking. These functions are manifested in different arrangements of the parts of the sentence. The grammatical function of word order § 115. The main function of word order is t o e x p r e s s g r a m m a t i c a l r e l a t i o n s a n d d e t e r m i n e t h e g r a m m a t i c a l s t a t u s o f a w o r d by fixing its position in the sentence. There exist two ways of arranging words - direct word order and inverted word order. Direct word order § 116. The most common pattern for the arrangement of the main parts in a declarative sentence is Subject - Predicate - (Object), which is called direct word order. Direct word order is also employed in pronominal questions to the subject or to its attribute. Direct word order allows of only few variations in the fixed pattern, and then only for the secondary parts. Thus if there are two objects, the indirect one precedes the direct one, or the prepositional follows the direct one. Thus the pattern has the following form: Subject - Predicate - Indirect object - Direct object Direct object - Prepositional object The birds have come. Ann has seen this film. The boy gave me no answer. The boy gave no answer to me. As to other secondary parts of the sentence, such as attributes and adverbial modifiers, their position is less fixed. Usually those words that are closely connected tend to be placed together. Accordingly secondary parts referring to their headwords are placed close to them, or are incorporated into, or else frame them up. Thus attributes either premodify or postmodify or frame up their headwords: a bright morning, the problems involved, the scene familiar to us, the happiest man alive, the best skier in the world. Adverbials and different form words seem to be the most movable parts in the sentence. Their mobility is partly accounted for by their varied reference to different parts of the sentence. Inverted word order § 119. Another common pattern of word order is the inverted one (or inversion). We distinguish f u l l i n v e r s i o n (when the predicate precedes the subject, as in Here comes the lady of the house) and p a r t i a l i n v e r s i o n (when only part of the predicate precedes the subject, as in Happy may you be!). Some grammarians also distinguish d o u b l e i n v e r s i o n (when parts of the predicate are placed separately before the subject, as in Hanging on the wall was a picture). § 120. In some cases inversion may be taken as a normal order of words in constructions with special communicative value, and is thus devoid of any special colouring. In other cases inversion is a sort of reordering for stylistic effect or for emphasis. First we enumerate those cases where inversion is a normal word order. 1. Inversion is used to distinguish between the communicative types of sentences. With this function it is employed in: a) G e n e r a l q u e s t i o n s , p o l i t e r e q u e s t s a n d i n t a g q u e s t i o n s . Is it really true? Won’t you have a cup of tea? You are glad to see me, aren’t you? b) P r o n o m i n a l q u e s t i o n s , e x c e p t q u e s t i o n s t o t h e s u b j e c t a n d i t s attribute, where direct word order is used. What are the police after? c) T h e r e - s e n t e n c e s w i t h t h e i n t r o d u c t o r y n o n - l o c a l t h e r e , followed by one of the verbs denoting existence, movement, or change of the situation . There has been an accident. There is nothing in it. There appeared an ugly face over the fence. There occurred a sudden revolution in public taste. There comes our chief. d) E x c l a m a t o r y s e n t e n c e s e x p r e s s i n g wish, despair, indignation, or other strong emotions. Long live the king! Come what may! e) E x c l a m a t o r y s e n t e n c e s w h i c h a r e n e g a t i v e i n f o r m b u t p o s i t i v e in meaning. Have I not watched them! (= I have watched them.) Wouldn’t that be fun! (= It would be fun.) f) N e g a t i v e i m p e r a t i v e s e n t e n c e s . Don’t you do it. 2. Inversion is used as a grammatical means of subordination in some complex sentences joined without connectors: a) I n c o n d i t i o n a l c l a u s e s . Were you sure of it, you wouldn’t hesitate. Had she known it before, she wouldn’t have made this mistake. b) I n c o n c e s s i v e c l a u s e s . Proud as he was, he had to consent to our proposal. c) I n t h e s e c o n d p a r t o f a s e n t e n c e o f p r o p o r t i o n a l a g r e e m e n t (although inversion is not obligatory in this case). The more he thought of it, the less clear was the matter. 3. Inversion is used in sentences beginning with adverbs denoting place. This usage is traditional, going back to OE norms. Here is another example. There goes another bus (туда идет еще один автобус, еще автобус идет). 4. Inversion is used in stage directions, although this use is limited to certain verbs. Enter the King, the Queen. Enter Beatie Bryant, an ample blond. 5. Inversion may be used in sentences indicating whose words or thoughts are given as direct or indirect speech. These sentences may introduce, interrupt, or follow the words in direct or indirect speech, or may be given in parenthesis. “That’s him,” said Tom (Tom said). How did he know, thought Jack, miserably. Direct word order can also be used here. 6. Inversion is used in statements showing that the remark applies equally to someone or something else. I am tired. - So am I. He isn’t ready. - Neither is she. Note: If the sentence is a corroboration of a remark just made, direct word order is used. You promised to come and see me. - So I did. We may meet him later. - So we may. The emphatic and communicative functions of word order § 121. The second function of word order is t o m a k e p r o m i n e n t o r e m p h a t i c that part of the sentence which is more important or informative in the speaker’s opinion. These two functions (to express prominence or information focus, and emphasis) are different in their purpose, but in many cases they go together or overlap, and are difficult to differentiate. Prominence and emphasis are achieved by placing the word in an unusual position: words normally placed at the beginning of the sentence (such as the subject) are placed towards the end, whereas words usually occupying positions closer to the end of the sentence (such as objects and predicatives) are shifted to the beginning. End position is always emphatic for the subject. Very often this reordering results in the detachment of the subject. Must have cost a pretty penny, this dress of yours! Fronting of an object or a predicative is also often accompanied by detachment. Horrible these women are, ugly, dirty. Many and long were the conversations they held through the prison wall. For debt, drink, dancers he had a certain sympathy; but the pearls - no! If the object is prepositional, the preposition may be put after the verb or verb-group, or else after the whole sentence. This nowadays one hears not of. However, front position of an object does not always mean that this part is emphasized. In some cases this sort of reordering is employed to get the predicate (or what is left of it) emphasized. Talent Mr. Macowber has, capital Mr. Macowber has not. Front position is emphatic for adverbials (of time, manner, degree) usually attached to the predicate. It is often accompanied by inversion. Well do I remember the day. Many a time has he given me good advice. With words functioning now as adverbs, now as postpositions, front position reveals their adverbial nature most distinctly, as postpositions are never placed here. With this reordering the emphasis is thrown upon the predicate. Off he went. Up they rushed. For attributes emphasis may be achieved by putting them after their headword. In this way the modifier becomes the focus and has the principal stress of the word-group. The day following was to decide our fate. Note: In assessing the emphatic effect of a postmodifying attribute we should bear in mind that for certain attributes this position is normal (see § 86). However, the fixed patterns in English limit the opportunities to shift prominence or emphasis from one part of the sentence to another, especially for main parts. Therefore prominence and emphasis are generally achieved not by reordering, but by using special constructions. One such construction used for emphasizing the subject is the introductory non-local there + verb + noun, followed by an attributive clause. There was a girl whom he loved. There comes a time when one should make up one’s mind. Another device for shifting emphasis is the construction with the introductory it, the main information being supplied by the subordinate clause. By means of this construction emphasis may be thrown upon any part of the sentence, except the predicate. Such sentences are called cleft sentences. This can be illustrated by the following: It was she who opened the door. It is not easy to find a position. It was to Moscow that she went. Special emphasis on words functioning as direct or indirect object may be achieved by the use of the passive construction, in which the words to be emphasized are moved either to front position or closer to the end. Compare the sentences: The teacher gave the children an easy task. The children were given an easy task by the teacher. An easy task was given to the children by the teacher. The linking function of word order § 122. The third function of word order is t o e x p r e s s c o n t i n u i t y o f t h o u g h t in sentences (or clauses) following one another. This continuity is often supported by demonstrative pronouns and adverbs. Some people looked down on him. Those people he despised. They must sow their wild oats. Such was his theory. And, oh, that look! On that look Euphemia had spent much anxious thought. Women are terribly vain. So are men - more so, if possible. Similarly, for purposes of enumeration, a word (or words) marking continuity is sometimes placed at the beginning of the sentence, with the verb immediately following. Next comes the most amusing scene.