youth dance cultures, doofs & alternate spiritualities

advertisement

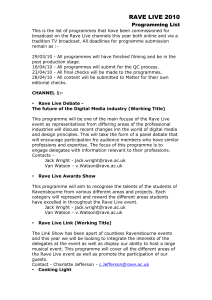

YOUTH DANCE CULTURES, DOOFS & ALTERNATE SPIRITUALITIES: Short Summary Notes as A Basis for Missional Reflection and Action Origins Since the late 1980s various youth sub-cultures have emerged around the world associated with music, dance, Countercultural lifestyles and alternate forms of spirituality. One of the more intriguing subcultures is associated with what is called “rave culture” or “doofing”. Rave culture involves youth from various socio-economic backgrounds participating in all-night dance parties characterised by electronic musical styles known as “psi”, “trance”, “house” and so on. The term “doofing” refers to the repetitive drum-beat that sounds like doof, doof, doof. There are two forms of rave culture: commercial and underground. The original form of doofing began as an underground youth subculture in 1988 in England, which quickly spread throughout Europe, Australia and North America. As the underground activities began to attract substantial numbers of youth, some savvy entrepreneurs developed a commercial partly “mainstream” form of dance parties. However, the underground style persists and continues to attract large numbers of youth. For example, the investigative journalist programme “Four Corners” estimated that every weekend there are at least 100,000 youths participating in doof parties in Australia. While the annual Burning Man event in America likewise attracts enormous crowds of people out in to the desert landscape. Other major events have taken place in Goa in India, and on the famous resort island of Ibiza. The Ethos The underground form of doofing is characterised by a slogan PLUR, which is an acronym for Peace, Love, Unity and Respect. The ethos of a rave party is that anyone, no matter what their beliefs or socio-economic and educational status, can participate. One does not need to be a skilled dancer to belong. In fact the notion of “respect” carries with it the sense that those who dance are not to be judged on the basis of their appearance or skills on the dance floor. Parties & Protest Much of the underground doof events combine dance with activism on a range of socio-political issues. These issues tend to concentrate on resisting economic globalisation that stems from the G8 and World Trade Organisation conferences, or from corporations like Nike, Microsoft and McDonalds. Doof activists have been prominent in their anti-globalisation rallies in Seattle, Genoa and Melbourne. Other issues relate to specific road protests, anti-logging of forests, anti-uranium mining, anti-Iraq war protests and so forth. Ecological issues loom large on the radar screen for doof activists. Spirituality The slogan PLUR might evoke the hippy ethos of the late 1960s, and whilst comparisons might be made about utopian ideals, the doof culture needs to be appreciated on its own grounds. Doof gatherings attract a spectrum of youth that includes advocates of anarchism, eco-spirituality, neo-paganism and so forth. One of the central players in a doof party is the disc jockey who plays the music associated with light shows. The DJs are often highly esteemed figures who lead the partygoers into altered states of consciousness on the dance floor. While some participants do ingest drugs, like ecstasy, it would be erroneous to generalise that all participants are simply into chemically induced trances. Many dancers will express their sense of interconnectedness or oneness or unity with fellow dancers, or speak of moments of transcendence, of experiencing divinity, or God. Some DJs are known as techno-shamans because of the links between the music, the dancing, the ambience, the drugs and the sense of consciousness evoked in these events. Some of these techno-shamans are committed to neo-pagan or earth-centred spiritualities. The link between the party and eco-protests neatly slipstreams into the spirituality associated with nature divinities, mother goddess icons, new age consciousness and so on. The spiritual ethos is also associated with notions derived from the anarchist Hakim Bey about creating “Temporary Autonomous Zones” or TAZ. The creation of a TAZ is where a group gathers together in a public zone, be it urban or rural, and temporarily alters that landscape by their presence, as expressed in the dance. Once the dance event is over, the place is restored to its pre-event shape. The creation of a TAZ in the doof scene is associated with the idea of establishing sacred zones, and of humans re-connecting with the natural environment. Sometimes artistic expressions are associated with this, such as the use of wrecked cars that are erected in a shape known as “Car-henge” (mimicking Stonehenge). In the alternate countercultural centre of Australia, at a place in northern New South Wales known as Nimbin, neo-pagan shamanism flourishes amongst both sedentary settlers and nomadic loosely affiliated tribes of people (known as ferals or rainbow people). The neo-pagan shamans of this region are active in eco-protests as well as organising doof parties in the bushland. The Missional Challenge The above notes are very cursory and incomplete. However it ought to be apparent that on a global scale there is a significant countercultural ferment amongst many youth, and doof cultures provide a focal point for many of them. As some are nomadic, the need for chaplains committed to nomadism is one trajectory requiring missional reflection and action. As alternate spiritualities loom large on the horizons of doof cultures, it is clear that Christians have before them an unreached people group to engage in discipleship with. There are a few missional experiments taking place in England and Australia with Christian DJs operating in the Rave scene. However this is a frontier area that is in danger of being ignored until the proverbial horse bolts from the barn. These notes do not propose any missional solutions other than raising the obvious need for contextual cross-cultural research followed by enculturated efforts at discipleship. I believe that this is an important issue requiring some case study work in the Lausanne Issue Group, and that in our position paper this youth subculture needs to be formally recognised as an unreached people group for contemporary missions. RELEVANT READING MATTER Jose Bove & Francois Dufour, The World is Not For Sale: Farmers Against Junk Food, London: Verso, 2001. E. Bailey, Implicit Religion in Contemporary Society, Kampen, The Netherlands: Kok Pharos, 1997. B. Brewster & F. Broughton, Last Night a DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc Jockey, Cambridge: Grove Press, 2000. F. Cole & M. Hannan, “Goa Trance” Perfect Beat, Volume 3, number 3 (1997), pp. 114. M. Corsten, “Ecstasy as ‘this worldly path to salvation’: the techno youth scene as a proto-religious collective,” in L. Tomasi (ed) Alternative Religions Among European Youth, Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999. Anthony D’Andrea, “Global nomads: techno and New Age as transnational countercultures in Ibiza and Goa,” in Graham St. John (ed) Rave Culture and Religion, London: Routledge, 2004. Eric Davis, Techngnosis: Myth, Magic and Mysticism in the Age of Information, New York: Three Rivers Press, 1998. Eric Davis, “Hedonic Tantra: golden Goa’s trance transmission,” in Graham St. John (ed) Rave Culture and Religion, London: Routledge, 2004. Alan Dearling and Brendan Hanley, Alternative Australia: Celebrating Cultural Diversity, Lyme Regis: Enabler Publications, 2000. J. Fritz, Rave Culture: An Insider’s Overview, Canada: Smallfry Press, 1999. J. Gilbert & E. Pearson, Discographies: Dance Music, Culture and the Politics of Sound, London: Routledge, 1999. D. Hill, “Mobile Anarchy: the house movement, shamanism and community,” in T. Lyttle (ed) Psychedelics Reimagined, New York: Autonomedia, 1999. R. Hollands, “Divisions in the Dark: youth cultures, transitions and segmented consumption spaces in the night-time economy,” Journal of Youth Studies, Volume 5, number 2 (2002), pp. 153-171. S. Hutson, “Technoshamanism: spiritual healing in the rave subculture,” Popular Music and Society, Volume 23, number 3 (1999), pp. 53-77. S. Hutson, “The rave: spiritual healing in modern western subcultures,” Anthropological Quarterly, Volume 73, number 1 (2000), pp. 35-49. A. Ivakhiv, Claiming Sacred Ground: Pilgrims and Politics at Glastonbury and Sedona, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001. Robert V. Kozinets & John F. Sherry, “Dancing on common ground: exploring the sacred at Burning Man,” in Graham St. John (ed) Rave Culture and Religion, London: Routledge, 2004. George McKay (ed) DiY Culture: Party and Protest in Nineties Britain, London: Verso, 1998. M. Maffesoli, The Time of the Tribes: The Decline of Individualism in Mass Society, London: SAGE, 1996. B. Malbon, Clubbing: Dancing, Ecstasy and Vitality, London: Routledge, 1999. Michael Niman, People of the Rainbow: A Nomadic Utopia, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997. Ciaran O’Hagan, “Sounds of the London Underground: gospel music and Baptist Worship in the UK garage scene,” in Graham St. John (ed) Rave Culture and Religion, London: Routledge, 2004. Sarah Pike, Earthly Bodies, Magic Selves: Contemporary Pagans and the Search for Community, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. S. Redhead (ed) Rave Off: Politics and Deviance in Contemporary Youth Culture, Aldershot: Avebury, 1993. S. Redhead (ed) The Clubcultures Reader: Readings in Popular Cultural Studies, Blackwell: Oxford, 1997. Graham St. John (ed) FreeNRG: Notes From The Edge of the Dance Floor, Melbourne: Common Ground Publishing, 2001. Graham St. John (ed) Rave Culture and Religion, London: Routledge, 2004. Arun Saldanha, “Goa trance and trance in Goa: smooth striations,” in Graham St. John (ed) Rave Culture and Religion, London: Routledge, 2004. N. Saunders, A. Saunders and M. Pauli, In Search of the Ultimate High: Spiritual Experiences through Psychoactives, London: Rider, 2000. S. Thornton, Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital, Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995. Des Tramacchi, “Field Tripping: psychedelic communitas and ritual in the Australian bush,” Journal of Contemporary Religion, Volume 15, number 2 (2000), pp. 201-213. K. Westerhausen, Beyond the Beach: An Ethnography of Modern Travellers in Asia, Bangkok: White Lotus, 2002.