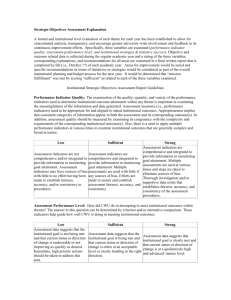

The conceptual framework for measuring quality

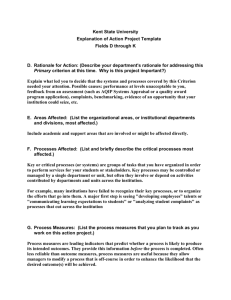

advertisement