roman medieval

advertisement

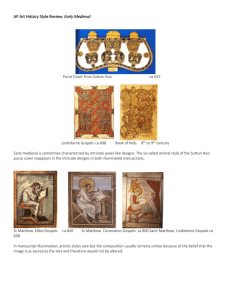

Chapter 16 Europe After the Fall of Rome: Early Medieval Art in the West -Notes Historians once referred to the thousand years (roughly 400-1400) between the dying Roman Empire’s adoption of Christianity as its official religion and the rebirth (Renaissance) of interest in classical antiquity as the Dark Ages. Scholars and lay persons alike thought this long “interval” - between the ancient and what was perceived as the modern European world - was rough and uncivilized, and crude and primitive artistically. They viewed these centuries - dubbed the Middle Ages - as simply a blank between (in the middle of) two great civilizations. This negative assessment, a legacy of the humanist scholars of Renaissance Italy, persists today in the retention of the noun Middle Ages and the adjective medieval to describe this period and its art. The force of tradition dictates that we continue to use those terms, even though modern scholars long ago ceased to see the art of medieval Europe as unsophisticated or inferior. Art historians date the art of the Early Middle Ages from 500 to 1000. Early medieval civilization in Western Europe represents a fusion of Christianity, the Greco-Roman heritage, and the cultures of the non-Roman peoples north of the Alps. Although the Romans called everyone who lived beyond the classical worlds frontiers “barbarians,” many northerners had risen to prominent positions within the Roman army and government during the later Roman Empire. Others established their own areas of rule, sometimes with Rome’s approval, sometimes in opposition to imperial authority. In time, these non Romans merged with the citizens of the former northwestern provinces of Rome and slowly developed political and social institutions that have continued to modern times. Over the centuries a new order gradually replaced what had been the Roman Empire, resulting eventually in the foundation of today’s European nations. The Art of the Warrior Lords Rome’s power waned in Late Antiquity, armed conflicts and competition for political authority became common place among the non Roman people of Europe - Huns, Vandals, Merovingians, Franks, Goths, and others. Once one group established it self, another often pressed in behind and compelled it to move on. The Visigoths, for example, who once held northern Italy and formed a kingdom in southern France, were forced south into Spain under pressure from the Franks, who had crossed the Rhine River and established themselves firmly in France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and parts of Germany. The Ostrogoths moved to Italy, establishing their kingdom there only to be removed 100 years later by the Lombards. In the North Anglo Saxons controlled what had been Roman Arian. Celts inhabited France and parts of the British Isles, including Ireland, the one area of Western Europe that Roman never colonized. In Scandinavia the great seafaring Vikings ruled. Art and Status Art historians do not know the full range of art and architecture these non Roman people produced. What has survived is not truly representative and consists almost exclusively of small “status symbols” - weapons and items of personal adornment such as bracelets, pendants, and belt buckles that archeologists have discovered in lavish burials. Earlier scholars, who viewed medieval art through a Renaissance lens, ignored these “minor arts” because of their small scale, seemingly utilitarian nature, and abstract ornament, and because the people who made them rejected the classical idea that that the representation of organic nature should be the focus of artistic endeavor. In their own time, these objects, which often display a high degree of technical and stylistic sophistication, were regarded as treasures. They enhanced the prestige of those who owned them and testified to the stature of those who were buried with them. Merovingian Fibulae Characteristic of the prestige ornaments was the fibula the decorative pins favored by the Romans and were used to hold together garments of men and women. Made of bronze, silver, or gold, they were often decorated with inlaid precious and semi precious stones. Fibulae were symbols of power and prestige. The entire surface is covered with decorative pattern carefully adjusted to the shape of the form to describe and amplify it. Often zoomorphic elements were so successfully integrated into this type of highly disciplined, abstract decorative design that they became almost unrecognizable. A fish may be discerned in the in the lower half of the fibulae. The looped forms around the edges are stylized eagle heads. Burial Ships In 1939, a treasure laden ship was discovered in a burial mound at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk, England. It epitomizes the early medieval tradition of burying great lords with rich furnishings. Of the rich finds at Sutton Hoo, the most extraordinary is a purse cover decorated with cloisonné-enamel plaques. The cloisonné technique is documented as far back as the New Kingdom in Egypt. Metal workers produced cloisonné jewelry by soldering small strips of metal or cloisons (French for partitions), edge up, to a metal background, and then filling the compartments with semi precious stones, pieces of colored glass, or glass paste fired to resemble sparkling jewels. Today we call this enameling. Cloisonné is a cross between mosaic and stained glass. On our piece there a four symmetrically arranged groups of figures that make up the lower row. The end groups consist of a man standing between two beasts. He is frontal they are in profile. As you should remember this is called a heraldic grouping and has its roots back in ancient Ur. The arrangement also carried a powerful contemporary message. It is a pictorial counterpart to the epic saga of the eras when heroes, such as Beowulf battle and conquer monsters. The two center groups represent Eagles battling ducks. The convex beaks of the eagles fit against the concave beaks of the ducks. The two figures fit together so snugly that they seem to be a single dense abstract design. This is also true of the man beast motif. Above these figures are three geometric designs. The outer ones are clear and linear in style. In the central design, there is an interlace of pattern that turns into writhing animal figures. Elaborate interlace patterns are characteristic of many times and places, notably in the Islamic world. But the combination of interlace with animal figures was uncommon outside the realm of the early medieval warlords. In fact, metal craft with a vocabulary of interlace patterns and other motifs beautifully integrated with animal form were without doubt the art of the early Middle Ages in the West. Interest in it was so great that the colorful effects of jewelry designs were imitated in the painted decorations of manuscripts, in stone sculpture, in the masonry of churches, and in sculpture in wood, an especially important medium in Viking art. Vikings In 793 the pagan traders and pirates known as Vikings (named after the viks coves or “trading places” - of the Norwegian shoreline) set sail from Scandinavia and landed in the British Isles. They destroyed the Christian monastic community on Lindisfarne Island off the Northumbrian (northeast) coast of England. Shortly after, these Norsemen (North men) attacked a monastery at Jarrow in England, as well as one off the coast of Scotland. From this time until the mid 11th century the Vikings were the terror of Western Europe. From their great ships they seasonally raided the coasts of the West. Their fast seaworthy longboats took them on wide ranging voyages, from Ireland to Russia, Iceland and Greenland, and even as far as Newfoundland in North America, long before Columbus. The Vikings were intent on colonizing the lands they occupied by conquest. They were exceptional in organization, administration, and war, enabling them to govern large areas of Ireland, England, and France, as well as, the Baltic regions and Russia. For a while in the early 11th century, the whole of England was part of the Danish empire. When the Vikings settled in northern France in the early 10th century, their territory became known as Normandy. Those that lived there became known as Normans. Later, a Norman Duke, William the Conqueror, sailed across the English Channel and invaded and became the master of Anglo-Saxon England. The Art of the Vikings was early associated with their great wooden ships. One burial ship, found in Oseberg, Norway, was more than 70 feet long and contained the remains of two women. It size and carved wooden ornament attested to the greatness of the one buried there. Long ago robbed of its many precious objects, there still remained some of the carving. Our example is a wooden animal head post. It combines in one composition the image of a roaring beast and the deftly controlled and contained pattern of tightly interwoven animals that writhe, gripping and snapping in serpentine fashion. This piece is a powerfully expressive example of the union of two fundamental motifs in the art of the warrior lords of the northern frontiers of the old Roman Empire - the animal and interlace pattern. Animal Art on a Church By the 11th century, much of Scandinavia had become Christian, but Viking artistic traditions continued. No where is this more evident than in a decoration of the portal of a stave church (staves are wedge shaped timbers placed vertically), at Urnes, Norway. The portal and a few staves are all that is preserved of the mid 11th century church. It is preserved because it was incorporated in the walls of a 12th century church. Gracefully elongated animal forms intertwine with flexible plant stalks and tendrils in spiraling rhythm. The effect of natural growth is astonishing, yet it has been subjected to the designer’s highly refined abstract sensibility. This intricate style is the culmination of three centuries of Viking inventiveness (8th - 11th centuries). Hiberno - Saxon Art In 432 St. Patrick established a church in Ireland and began the Christianization of the Celts. The new converts developed a monastic organization, liturgical practices, and calendar of holidays different from that of the Church of Rome. This independence was do partly to the isolated, inaccessible and inhospitable places that the monasteries were located. These monasteries evangelized England and Scotland setting up monasteries there. These places later became great centers of learning and established monasteries in other countries. A distinct style of art developed within these monasteries that has been called Hiberno - Saxon (Hiberno was the ancient name of Ireland), or Insular to denote the Irish English Islands where it was produced. Its most distinctive products were illuminated manuscripts of the Christian Church. Liturgical books were the primary vehicles in the effort to Christianize the British Isles. They literally brought the Word of God to a predominantly illiterate population who regarded the monks’ sumptuous volumes with awe. Books were scarce, jealously guarded treasures. Most of them were housed in the libraries and scriptoria (writing studios) of monasteries or major churches. Illuminated books are the most important extant monuments of the brilliant artistic culture that flourished in Ireland and Northumbria during the seventh and eighth centuries. Carpets and Crosses The marriage between Christian imagery and the animal lace style of the North may be seen in the cross inscribed page of the Lindisfarne Gospels. This type of page is called a carpet page because they resembled textiles. The book produced in the Northumbrian monastery on Lindisfarne Island (hence the name), contains several ornamental pages and exemplify Hiberno - Saxon art. According to a later colophon (an inscription, usually on the last page, providing information regarding the books manufacture), Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne between 698 and 721 wrote the Lindisfarne Gospels. “for God and Saint Cuthbert” Cuthbert’s relics recently had been deposited in the Lindisfarne church. The patterning and detail of our example are very intricate. Serpentine interlacements of fantastic animals devour each other, curling over and returning to their writhing elastic shapes. The rhythm of expanding and contracting forms produces a most vivid effect of motion and change. But it is held in check by the regularity of the design and by the dominating motif of the inscribed cross. The cross stabilizes the rhythms of the serpentines and perhaps by contrast with its heavy immobility, seems to heighten the effect of motion. The illuminator placed the motifs in detailed symmetries, with inversions, reversals, and repetitions that must be studied to appreciate their maze like complexity. The zoomorphic forms intermingle with clusters and knots of line, and the whole design vibrates with energy. The color is rich yet cool. Saint Matthew All the works viewed so far display the Northern artists’ preference for small, infinitely complex, and painstaking designs. Some exceptions exist. Some insular manuscripts are clearly based on compositions from classical pictures from imported Mediterranean books. In our example, the portrait of Saint Matthew in the Lindisfarne Gospels, The artist’s model must have been one of the illustrated Gospel books a Christian missionary brought from Italy to England. Author portraits were familiar features of Greek and Latin books, and similar representations of seated poets and philosophers writing or reading about ancient art. Unlike the cross page of the same book, the Lindisfarne Evangelist portrait follows the long tradition of Mediterranean manuscript illumination. Matthew sits in his study composing his account of the life of Christ. A curtain sets the scene indoors, as in classical art, and his seat is shown at an angle suggesting the original image employed classical perspective. The painter of scribe labeled Matthew in a curious combination of Greek (O Agios, saint - written in Roman rather than Greek characters) and Latin (Mattheus), perhaps to lead the prestige of the two classical languages to the page. Greek was the language of the New Testament and Latin the Church of Rome. Matthew is accompanied by his symbol of a winged man. The figure behind the curtain (actually a disembodied head and shoulders) has been variously identified as Moses, holding the closed book of the Old Testament, in contrast with the open book of Matthew’s New Testament. This was a common juxtaposition in medieval Christian art and thought. The artist’s goal was not to copy the model image faithfully. He is uninterested in the pictorial illusionism of the Classical and Late Antique painting style. He conceived the subject in terms of line and color exclusively. The drapery folds are a series of sharp, regularly spaced, curving lines filled in with flat colors. The painter converted fully modeled forms bathed in light into the linear idiom of northern art. The result is not an inferior imitation of a Mediterranean prototype but a vivid new vision of the Evangelist. Illuminating the Word The greatest achievement of Hiberno - Saxon art in the eyes of most art historians is the Book of Kells the most elaborately decorated of the insular Gospel books. Medieval commentators agreed. One wrote in the Annals of Ulster for the year 1003 that this “great Gospel is the chief relic of the western world.” The Book of Kells is named after the monastery in southern Ireland that owned it. The manuscript was probably created for display on a church altar. From an early date it was housed in an elaborate metalwork box, befitting a greatly revered relic. The Book of Kells boasts an unprecedented number of full page illuminations, including carpet pages, evangelist symbols’ portrayals of the Virgin Mary and of Christ, New Testament narrative scenes, canon tables, and several instances of monumentalized and embellished words from the Bible. Our example opens the account of the nativity of Jesus in the Gospel of Saint Matthew. The initial letters of Christ in Greek (XPI, chi-rho-iota) occupy nearly the whole page although two words appear at the lower right. Autem (abbreviated simply as h) and generatio, together read “Now this is how the birth of Christ came about.” The page corresponds to the opening of Matthew’s Gospel, the passage read in the church on Christmas Day. The illuminator transformed the holy words into extraordinarily intricate abstract designs that recall Celtic and Anglo - Saxon metal work. The cloisonné - like interlace is not purely abstract pattern, the letter rho for example ends in a human head, and animals are at the base to the left of h generatio. Half figures of winged angels appear to the left of chi, accompanying the monogram as if accompanying Christ himself. Close observation reveals many other human and animal figures. High Crosses The preserved art of the early Middle Ages has been confined almost exclusively to small portable works. The high crosses of Ireland, erected between the 8th and 10th centuries, are exceptional in their mass and scale. Some of these monuments are more than 20 feet high and preside over burial grounds adjoining the ruins of monasteries at sites widely distributed throughout the Irish countryside and some places in England. The High Cross of Muiredach at Monasterboice, Ireland is one of the largest and finest examples. An inscription on the bottom of the west face of the shaft asks a prayer for a man named Muiredach. Most scholars identify him as as the influential Irish cleric of the same name who was the abbot of Monasterboice and died in 923. The cross probably marked the abbot’s grave. The concave arms of Muiredach’s cross are looped by four arcs that form a circle. The arms expand into squared terminals. The circle intersecting the cross identifies the type as Celtic. The early high crosses bear abstract designs, especially the familiar interlace pattern. But the latter ones, like our example, have figured panels, with scenes from the life of Christ or, occasionally, fantastic animals or events from the life of some Celtic saint. At the center of the west side of Muiredach's cross is a depiction of the Crucified Christ. On the east side the risen Christ stands as a judge of the world, the hope of the dead. Below him the souls of the dead are being weighed on scales - a theme that sculptors of the 12th century church portals took up with extraordinary force. Carolingian Art On Christmas Day of the year 800, Pope Leo III crowned Charles the Great (Charlemagne), King of the Franks since 768, as Emperor of Rome (800 - 814). In time Charlemagne came to be seen as the first Holy (Christian) Roman Emperor, a title his successors in the West did not formally adopt until the 12th century. Born in 742 when Northern Europe was still in chaos, Charlemagne consolidated the Frankish kingdom his father and grandfather bequeathed him and defeated the Lombards in Italy. He thus united Europe and laid claim to reviving the glory of the Ancient Roman Empire. He gave his name (Carolus Magnus in Latin) to an entire era, the Carolingian period. Charlemagne’s official seal bore the words renovatio imperii Romani (renewal of the Roman Empire). The Carolingian Renaissance was a remarkable historical phenomenon, an energetic, brilliant emulation of art, culture, and political ideals of Early Christian Rome. Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire waxing and waning for a thousand years and with many hiatuses, existed in central Europe until Napoleon destroyed it in 1806. Imperial Imagery Revived When Charlemagne returned home from his coronation in Rome, he ordered the transfer of an Equestrian statue of the Ostrogothic King Theodoric from Ravenna to his palace complex at Aachen Germany. It was used as an inspiration for a ninth century bronze statuette of a Carolingian Emperor on horseback. Many scholars believe it is of Charlemagne or his grandson Charles the Bald (840 - 877). This statuette is much like the statue of Marcus Aurelius, which you should recall, was preserved because it was thought to be Constantine the first Christian Roman Emperor. Because of this it was not melted down as were most other portraits of pagan Roman Emperors. He is larger than the horse - focusing on the emperor, he sits rigidly, he wears imperial robes rather than a general’s armor, on his head is a crown. His outstretched arm holds a globe the symbol of world domination. This portrait shows the power of the New Holy Roman Empire under Charlemagne and his successors. The Art of the Book Charlemagne was a sincere admirer of learning, the arts, and classical culture. He and his successors and the scholars under their patronage placed a very high value on books, both sacred and secular, importing many and producing far more. The Coronation Gospels also known as the Gospel Book of Charlemagne. An old and probably inaccurate legend says the book was found on Charlemagne’s knees when in the year 100; Emperor Otto III opened the tomb. The text is written in gold letters on purple vellum. The four major full page illuminations show the four Gospel authors at work. Our example is of Saint Matthew and should be compared to the Lindisfarne portrait. Instead of flat and linear the technique is illusionistic. Light and shadow create form rather than line and color. The furnishings are Roman and there is a return to landscape. This classical revival was one of many components of Charlemagne’s program to establish Aachen as the capital of a renewed Christian Roman Empire. Ebbo Gospels The classicizing style of the Coronation Gospels also suddenly appeared in other areas of the Carolingian world. Court schools and monasteries employed a wide variety of styles derived from Late Antique prototypes. Another Saint Matthew was made for Archbishop Ebbo of Reims, France. It may be an interpretation of another image. The illustrator in the Ebbo Gospels replaced classical calm and solidity of the Coronation Gospels with an energy that amounts to frenzy. Matthew (the winged man in the upper right identifies him) writes in frantic haste. His hair stand up on end, his eyes open wide, the folds on his robe writhe and vibrate. The landscape seems alive. The border even depicts action. The illustrator of the Ebbo Gospels translated a classical prototype into a new Carolingian vernacular. The master painter brilliantly merged classical illusionism and the North’s linear tradition. Bejeweled Books The sumptuous and portable objects of the medieval warrior lords continued under Charlemagne and his successors. They commissioned numerous works of costly materials. Book covers were mad od Gold Jewels and Ivory. The Gold and Gems not only glorified the Word of God but also evoked heavenly Jerusalem. One of the most luxurious Carolingian book covers was fashioned in one of the workshops of the court of Charles the Bald. It was later added to the Lindau Gospels. This monumental conception depicts a youthful Christ nailed to the cross surrounded by pearls and jewels that are raised on golden claw feet so they can catch and reflect the light more brilliantly and protect the gold from denting. The figure of Christ is beardless and not suffering. In contrast the other figures of angels, the Virgin Mary and Saint John, and the personifications of the Sun and Moon are shown with vivacity and nervous energy. Architecture Charlemagne also encouraged the use of Roman building techniques. As in sculpture and painting, innovations made in the reinterpretation of Earlier Roman Christian sources became fundamental to the subsequent development of northern European architecture. For his models, Charlemagne went to Rome and Ravenna. The plan of Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel at Aachen, Germany resembles that of San Vitale. It is the first vaulted structure of the Middle Ages in the West. The Aachen plan is simpler and gains greater geometric clarity than San Vitale. It omits San Vitale's apse like extensions reaching from the central octagon into the ambulatory. The Carolingian conversion of a complex and subtle Byzantine prototype into a building that expresses robust strength and clear architectural articulation foreshadows the architecture of the 11th and 12th centuries and the style called Romanesque. So to does the treatment of the Palatine exterior where two cylindrical towers with spiral staircases flank the entrance portal. This was the first step toward the great dual - tower facades of churches in the West from the 10th century to the present. Ottonian Art Charlemagne’s empire lasted on 30 years after his death. Fighting among the successors ended with a treaty in 843 caused the empire to be divided into western, eastern, and central areas, very roughly foreshadowing the later nations of France and Germany and a third realm corresponding to a long strip of land stretching from the Netherlands and Belgium to Rome. Intensified Viking incursions in the West helped bring about the collapse of the Carolingians. Only in the mid 10th century did the eastern part of the former empire consolidate under the rule of a new Saxon line of German emperors, called after the names of its three most famous family members, the Ottonians. The three Ottos made headway against invaders from the East, and remained free from Viking attacks. They not only preserved but enriched the Carolingian culture. The Christian Church, which had become corrupt and disorganized, recovered in the 10th century under the influence of a great monastic reform encouraged and sanctioned by the Ottonians, who also cemented ties with Italy and the papacy. By the time the last of the Ottonian emperors died in the early 11th century, the pagan marauders had become Christianized and settled, and the monastic reforms had been highly successful. The Basilica Transformed The Ottonians built basilican churches with towering spires and imposing Westworks. The best preserved 10th century Ottonian basilica is Saint Cyriakus at Gernrode, Germany. Margrave Gero, the military governor, founded a monastery on the site in 961. Construction of the church began in the same year. In the 12th century a large apse replaced the western entrance, but the upper part of the Westworks remained intact, including the two cylindrical towers. The interior was heavily restored in the 19th century, but still retains its 10th century character. The church has a transept at the East with a square choir in front of the apse. The nave is one of the first in the west to incorporate a gallery between the ground floor arcade and the clerestory, a design that became very popular in the succeeding Romanesque era. Scholars have reached no consensus as to the purpose of these galleries. The nave arcade was also transformed at Gernrode by the adoption of the alternate support system. Heavy support piers alternate with columns, dividing the nave into vertical units and mitigating the tunnel like horizontality of the Early Christian basilica. The division continues into the gallery level, breaking the rhythm of an all column arcade and leading the eye upward. Later architects would call this “verticalization” of the basilican nave much further. Bishop Bernward was one of the great patrons of Ottonian art and architecture. He was a tutor of Otto III, and builder of the Abby church of Saint Michael at Hildesheim, Germany. It was constructed between 1001 and 1031. It was rebuilt after it was bombed in W.W.II. St. Michael's has a double transept plan, tower groupings, and a Westworks. The two transepts create eastern and western centers of gravity; the nave seems to be merely a hall that connects them. Lateral entrances leading into the aisles almost completely lose the basilican orientation toward the East. Bernward may have seen this variation of Basilican plan when he visited Rome and saw Trajan’s Forum and his basilica. Sculpture Saint Michael’s also has giant bronze (16’ 6” high) doors that depict scenes from Genesis on the right door and scenes from the Life of Christ on the right. The doors may have been based on the giant wooden carved doors of Santa Sabina in Rome which was near the place Bishop Bernward stayed while in Rome. Each door was cast in a single piece, which was an extraordinary achievement in lost wax casting. The inspiration for the scenes on the doors may have been illuminated books. The doors were in a place only monks would have passed through them. The door on the left, with scenes from Genesis, begins with the creation of Adam (at the top) and ending with the murder of Adam and Eve’s son Abel by his brother Cain (at the bottom). The right door recounts the life of Christ from the bottom up. It begins with the Annunciation and ends with the appearance to Mary Magdalene of Christ after the Resurrection. Together the doors tell the story of Original Sin and ultimate redemption, showing the expulsion from the Garden of Eden and the path back to Paradise through the Christian Church. Bishop Bernward also commissioned a bronze spiral column depicting the story of Jesus’ life in 24 scenes beginning with his baptism and ending with his entry into Jerusalem. It is preserved intact except for its later capital and missing surmounting cross. It is reminiscent of Trajan’s column is style with its spiral register detailing Christ’s life in relief. The scenes on the column are the missing episodes from the story told on the churches doors. Monumental Sculpture The Crucifix commissioned by Archbishop Gero was presented to the Cologne Cathedral in 970, demonstrates that there was an interest in reviving monumental sculpture. The image is carved in oak and then painted and gilded; the six foot tall image of Christ nailed to the cross is both a statue and a reliquary a shrine for sacred relics). A compartment in the back of the head held a Host. A later story tells how a crack developed in the wood and was miraculously healed. The Gero crucifix presents a dramatically different conception of Christ’s Crucifixion than the bejeweled cover of the Lindau Gospels. Instead of a youthful Christ, triumphant over death, the bearded Christ of the Cologne Crucifix shows a suffering Jesus that displays great emotional power. The sculptor depicted Christ’s humanity. Blood is running down the forehead, the face is contorted in pain and the body is slumping under its own weight. The muscles are stretched to the point of almost ripping apart. The halo behind the head alludes to the Resurrection, but all the viewer can sense is pain. This depiction of suffering would characterize much art of the Middle Ages. Illuminated Books Henry II (1002 - 1024) the last Ottonian emperor commissioned a book of Gospel readings for the Mass. The book is called the Lectionary of Henry II and was a gift to the Brandenburg Cathedral. Our example showing the Annunciation to the Shepherds depicts the angels telling the shepherds of Christ’s birth. The angel has just alighted on the hill with his wings still beating and the wind of his landing ignites his draperies. The scene incorporates much of what was at the heart of the classical tradition, including the rocky landscape setting with grazing animals common also in Early Christian art. The gold sky shows knowledge of Byzantine illuminations and mosaics. Emphasized more than the message itself are the power and majesty of God’s authority. Imperial Ideal Otto III is portrayed in a Gospel Book that takes his name. The illuminator represented the emperor enthroned, holding the scepter and cross inscribed orb that represent his universal authority, conforming to a tradition dating back to Constantine. At his sides are clergy representing the church ant the barons representing the state both aligned in his support. Stylistically remote from Byzantine art, the picture has clear political resemblance to the Justinian mural at San Vitale. Conclusion The last emperor of the Western Roman Empire died in 476. For centuries Western Europe, except for the Byzantine Empire’s hold on Ravenna, was home to competing groups of non-Romans. Constantly on the move, these peoples left behind monuments small in scale, but often of costly materials, expert workmanship, and sophisticated design. The permanent centers of artistic culture in the early Middle Ages were the monasteries that Christian missionaries established beyond the Alps and across the English Channel. There master painters illuminated liturgical books in a distinctive style that fused the abstract and animal lace forms of the native peoples with Christian iconography. When the Frankish Charlemagne was crowned Emperor of Rome in 800, imperial rule was reestablished in former Roman provinces. With it came a revival of interest in the classical style and monumental architecture, a tradition carried on by Charlemagne’s Carolingian and Ottonian successors. The ideal of a Christian Roman Empire gave partial unity to Western Europe in the 9th, 10th, and early 11th centuries. To this extent, ancient Rome lived on to the millennium, culminating with Otto III. The Romanesque period that followed, however, denied the imperial spirit that had prevailed for centuries - but not the notion of Western Christendom. A new age was about to begin, and Rome ceased to be the deciding influence. Europe found unity, rather in a common religious heritage, and a missionary zeal. By the year 1000, even more remote Iceland had adopted Christianity. The next task for the kings and church leaders of Europe was to take up the banner of Christ and attempt to wrest control of the Holy land from the Muslims.