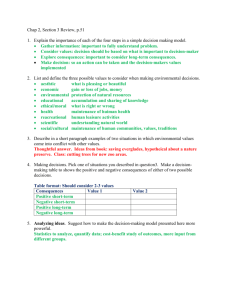

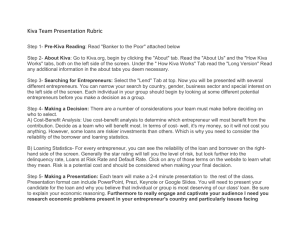

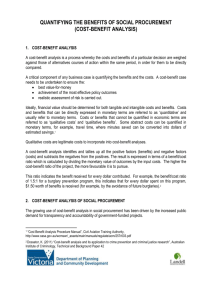

Using Cost-Benefit Analysis to Review Regulation

advertisement