Arthur Young on the agrarian improvements of the age, 1770-1771

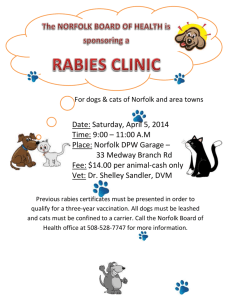

advertisement

Arthur Young on the agrarian improvements of the age, 1770-1771 (Improvements in stock breeding and arable agriculture. Arthur Young, The Farmer's Tour Through the East of England, I (1771), pp. 110-114, 150-151,156-157, 161-162; in D. B. Horn and Mary Ransome, eds., English Historical Documents, Vol. X, 1714-1783, N.Y: Oxford University Press, 1969, pp. 440-43) Mr. Bakewell of Dishley, one of the most considerable farmers in this country, has in so many instances improved on the husbandry of his neighbours, that he merits particular notice in this journal. His breed of cattle is famous throughout the kingdom; and he has lately sent many to Ireland. He has in this part of his business many ideas which I believe are perfectly new; or that have hitherto been totally neglected. This principle is to gain the beast, whether sheep or cow, that will weigh most in the most valuable joints: -there is a great difference between an ox of 50 stone, carrying 30 in roasting pieces, and 20 in coarse boiling onesand another carrying 30 in the latter, and 20 in the former. And at the same time that he gains the shape, that is, of the greatest value in the smallest compass; he asserts, from long experience, that he gains a breed much hardier, and easier fed than any others. These ideas he applies equally to sheep and oxen. In the breed of the latter, the old notion was, that where you had much and large bones, there was plenty of room to lay flesh on; and accordingly the graziers were eager to buy the largest boned cattle. This whole system Mr. Bakewell has proved to be an utter mistake. He asserts, the smaller the bones, the truer will be the make of the beast-the quicker she will fat-and her weight, we may easily conceive, will have a larger proportion of valuable meat: flesh, not bone, is the butcher's object. Mr. Bakewell admits that a large boned beast, may be made a large fat beast, and that he may come to a great weight; but justly observes, that this is no part of the profitable enquiry; for stating such a simple proposition, without at the same time shewing the expence of covering those bones with flesh, is offering no satisfactory argument. The only object of real importance, is the proportion of grass to value. I have 20 acres; which will pay me for those acres best, large or small boned cattle? The latter fat so much quicker, and more profitably in the joints of value; that the query is answered in their favour from long and attentive experience. Among other breeds of cattle the Lincolnshire and the Holderness are very large, but their size lies in their bones: they may be fattened to great loss to the grazier, nor can they ever return so much for a given quantity of grass, as the small boned, long horned kind. The breed which Mr. Bakewell has fixed on as the best in England, is the Lancashire, and he thinks he has improved it much, in bringing the carcass of the beast into a truer mould; and particularly by making them broader over the backs. The shape which should be the criterion of a cow, a bull, or an ox, and also of a sheep, is that of an hogshead, or a firkin; truly circular with small and as short legs as possible: upon the plain principle, that the value lies in the barrel, not in the legs. All breeds, the backs of which rise in the least ridge, are bad. I measured two or three cows, 2 feet 3 inches flat across their back from hip to hip-and their legs remarkably short. Mr. Bakewell has now a bull of his own breed which he calls Twopenny, which leaps cows at 5l. 5s. a cow. This is carrying the breed of horned cattle to wonderful perfection. He is a very fine bull-most truly made, according to the principles laid down above. He has many others got by him, which he lets for the season, from 5 guineas to 30 guineas a season, but rarely sells any. He would not take 200l. for Twopenny. He has several cows which he keeps for breeding, that he would not sell at 30 guineas apiece. Another particularity is the amazing gentleness in which he brings up these animals. All his bulls stand still in the field to be examined: the way of driving them from one field to another, or home, is by a little swish; he or his men walk by their side, and guide him with the stick where-ever they please; and they are accustomed to this method from being calves. A lad, with a stick three feet long, and as big as his finger, will conduct a bull away from other bulls, and his cows from one end of the farm to the other. All this gentleness is merely the effect of management, and the mischief often done by bulls, is undoubtedly owing to practices very contrary-or else to a total neglect. The general order in which Mr. Bakewell keeps his cattle is pleasing; all are fat as bears; and this is a circumstance which he insists is owing to the excellence of the breed. His land is no better than his neighbours, at the same time that it carries a far greater proportion of stock; as I shall shew by and by. The small quantity, and the inferior quality of food that will keep a beast perfectly well made, in good order, is surprising: such an animal will grow fat in the same pasture that would starve an ill made, great boned one. As I shall present leave Norfolk, it will not be improper to give a slight review of then husbandry which has rendered the name of this country so famous in the farming world. Pointing out the practices which have succeeded so nobly here, may perhaps be of some use to other countries possessed of the same advantages, but unknowing in the art to use them. From 40 to 60 years ago, all the northern and western, and a part of the eastern tracts of the county, were sheep-walks, let so low as from 6d. to Is. 6d. and 2s. an acre. Much of it was in this condition only 30 years ago. The great improvements have been made by means of the following circumstances. FIRST. By enclosing without assistance of parliament. SECOND. By a spirited use of marle and clay. THIRD. By the introduction of an excellent course of crops. FOURTH. By the culture of turnips well hand-hoed. FIFTH. By the culture of clover and ray-grass. SIXTH. By landlords granting long leases. SEVENTH. By the country being divided chiefly into large farms. In this recapsulation, I have inserted no article that is included in another. Take any one from the seven, and the improvement of Norfolk would never have existed… THE COURSE Of CROPS After the best managed enclosure, and the most spirited conduct in marling, still the whole success of the undertaking depends on this point: No fortune will be made in Norfolk by farming, unless a judicious course of crops be pursued. That which has been chiefly adopted by the Norfolk farmers is, 1. Turnips 2. Barley 3. Clover; or clover and ray-grass 4. Wheat. Some of them depending on their soils being richer than their neighbours ( for instance, all the way from Holt by Aylsham down through the Flegg hundreds) will steal a crop of pease or barley after the wheat; but it is bad husbandry, and has not been followedby those men who have made fortunes. In the above course, the turnips are (if possible) manured for ; and much of the wheat the same. This is a noble system, which keeps the soil rich; only one exhausting crop is taken to a cleaning and ameliorating one. The land cannot possibly in such management be either poor or foul .... LARGE FARMS. If the preceding articles are properly reviewed, it will at once be apparent that no small farmers could effect such great things as have been done in Norfolk. Inclosing, marling, and keeping a stock of sheep large enough for folding, belong absolutely and exclusively to great farmers. None of them could be effected by small ones-or such as are called middling ones in other countries.-Nor should it be forgotten, that the best husbandry in Norfolk is that of the largest farmers. You must go to a Curtis, a Mallet, a Barton, a Glover, a Carr, to see Norfolk husbandry. You will not among them find the stolen crops that are too often met with among the little occupiers of an hundred a year in the eastern part of the county. Great farms have been the soul of the Norfolk culture: split them into tenures of an hundred pounds a year, you will find nothing but beggars and weeds in the whole county. The rich man keeps his land rich and clean. These are the principles of Norfolk husbandry, which have advanced the agriculture of the greatest part of that county to a much greater height than is any where to be met with over an equal extent of country....