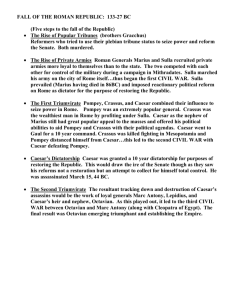

Plutarch`s Rome

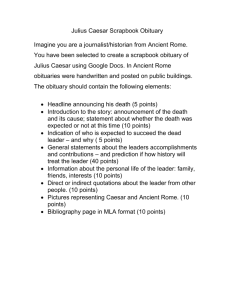

advertisement