THE ETHICS OF GENETIC ENGINEERING

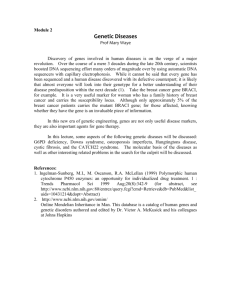

advertisement

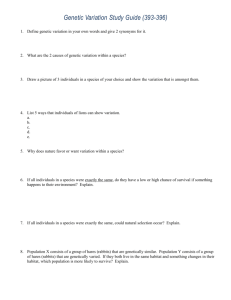

THE ETHICS OF GENETIC ENGINEERING David Cook When I shop in Sainsbury's or Tesco's, all the apples are the same shape, colour and texture. In my garden, all the apples are different. Nature has been altered by genetic engineering. The meat we eat is all too often produced by geneticists seeking to avoid fat. We take for granted genetic manipulation and engineering with food and animals. Inevitably scientists have seen the advantages of applying those techniques to humanity, especially in avoiding handicap. To do that scientists have been trying to understand our genetic make-up and to map the human genome. What is Genetics? Genetics is to do with our genes. They are made of DNA and are the basic building blocks of life. Every cell contains a full complement of genes and is carried in strands of DNA which are chromosomes. When new cells are replicated, each new cell will have characteristics that are governed by the genes passed on in the DNA. In other words, genes are the blue print of life. In human beings genes are responsible for the information that is carried in the egg and sperm, and which govern what each new child will inherit from his or her parents. Genetic disorders in the messages from the parents to the child may well result in handicap. The possibility that these 'abnormalities' may be detected and corrected is the underpinning aim of genetic research. One of the major international scientific projects is to 'map' out the human genetic blue print, or genome. Already we have discovered certain genes and their relationship to diseases like Huntington's Chorea, Muscular Dystrophy, Haemophilia and Down's Syndrome. This has led to the development of techniques, where diagnostic testing can be carried out in order to discover whether or not a person carries one of the genes for these diseases. In some areas it is also possible to correct 'abnormalities' within genes, usually by replacing faulty genes. Scientists are beginning to develop the ability to manipulate genes to 'improve' them. This raises all kinds of fears Will we get rid of all handicapped people? Should we try to develop a 'master' race? An Asian couple came to a genetics clinic. The wife was a carrier of Huntington's Chorea. They already had one child who was a carrier. The lady was pregnant again and wanted to know if the baby in the womb was a carrier. When they came for the test result, the counsellor told them the good news that the baby was normal. They asked if it was a boy or a girl. The counsellor enquired why they wanted to know. They said if it was a girl they would abort the child. They didn't want any more women in their community. On this basis, being female can be seen as a genetic abnormality. As we learn more about our genetic make-up and the significance in linkage to disease, fundamental moral questions are raised about what we should do with this knowledge. In all of this, it is important that we bear one question in mind. Just because we can do something, does that mean that we ought to do it? Does can imply ought? Testing and Genetic Screening Doctors have developed tests for various genetic problems. We can discover whether someone is a carrier of a gene which produces breast cancer or sickle cell anaemia. Such testing needs to be done with the full consent of the patient, who must understand the significance of the test for his or her life. Doing genetic testing for groups of the population, especially those who are known to be at risk, is called screening. This can be done on adults, children and even the unborn. There are advantages and problems with such screening. Knowing that you have a genetic propensity might help you prepare for a time when your life or its quality will be limited. Some genetically based diseases only develop when other factors come into play. Knowing that you are at risk means the possibility of changing your life style to reduce the danger of developing the disease. But such screening might select and target particular groups. We know that certain racial groups suffer from a higher risk of certain diseases than others. Screening might lead to discrimination against such groups. The results of such screening can have a positive benefit if we can do something to replace or manipulate the affected gene. The results might also lead to a great deal of anxiety about what will or might happen. It may also raise issues over whether to abort a child who is a carrier of a genetic disorder. Much of the current testing and screening in pregnancy leads to the almost automatic offer of abortion. This obviously prevents pain and suffering for the child, the parents and society, but it also kills a baby and raises questions about whether society really values and cares for people with a handicap. Ethical Problems with Testing and Screening Making some people understand the test, the significance of the results and what a positive test will mean for their life and circumstances is crucial. Doctors must ensure that patients do give voluntary, informed consent. That means patients must always be free to refuse a test. But if you do have a test will the results be private? A great many people like employers, insurance companies and building societies would dearly love this kind of information. If they thought you were likely to develop a disease, then they might not want to give you a job, a mortgage or life insurance. The European Commission is keen for us to carry an identity card, which would contain our medical history and our genetic make-up. Keeping that information confidential would be a nightmare and could lead to discrimination. If an individual has a test and discovers some genetic problem, it might be that meant his family – brothers and sisters as well as children – might also have the same disease. However, they might not know and not want to know. How could we find out if they did or didn't want such information without indicating that there was a likely problem? Does any of us have the right to inflict information on others, if they don’t wish it or even realise that such knowledge might affect them fundamentally. 2 The Significance of Such Information Discovering a genetic flaw in a foetus raises not just the possibility of an abortion, with the moral debate that creates, but questions about how we define 'normality'. If we want to avoid 'handicap', we need to be clear about what criteria we are using to define what is abnormal and what is normal. Once we have a piece of genetic information what are we to do with it as individuals, as doctors and as a society? Does it lead automatically to abortion on demand? For some it is better not to have the information in the first place, for that at least avoids the issue of abortion. How far would we take the idea of genetic fault or abnormality? If there were a gene for being born boring, should we test everyone for see who were carrying such a gene and then kill then all to make society a more lively and interesting place? Using the Information for Gene Therapy Gene therapy deals with the correction, alteration ore replacement of genes. The therapy will attempt to help the cell to function 'normally'. There are several areas where this technique has proved successful. But the benefits can be modified by problems. Sickle cell anaemia is a debilitating disease amongst Afro-Caribbeans. If it were possible to eradicate the disease, should we do so? The difficulty is that the same gene which is so terrible in a few cases provides natural immunity from malaria. Because scientists don't know how changing genetic make-up will affect the next generation of people, they have set limits to their research. They only work to change genes in a particular body, for the benefit of that individual – somatic cell therapy. They do not engage in germ line therapy, which might change our environment, the gene pool and the diversity of human beings. The ability to manipulate our genes raises … Hard Choices Given that we can replace or manipulate genetic material, this creates the possibility of designing babies to our own desired specifications. If I own a hop farm in Kent, then a baby with long arms would be helpful. If I run a deep sea diving business, a baby who needs little oxygen will save money. Such frivolous examples conceal the fact that women are using sperm from Nobel Prize winners to improve the intelligence of their children. This smacks of the Nazi attempts to produce a 'master race'. (or in this age of political correctness a 'ms. race'). The Wider Ethical Issues 3 Discovering new information about our genes and how they work has led to new kinds of test, drugs and treatments. Some drug companies and scientists, particularly in the USA, are keen to patent the genetic material and the ways they have developed new drugs and tests. They claim to 'own' the material. European scientists feel that genetic material 'belongs' to us all and humanity cannot be owned. The courts will decide, but this raises questions about the ownership of discoveries and the purpose of knowledge and research. Is it an end in itself or a means to another end, e.g. benefiting humanity? Commercial exploitation is affecting the practice of science. Individuals whose genetic material is used in new developments are claiming that they should have a share of any profits which result. Drug companies which fund research are asking for value for their money and are looking for adequate returns or else they won't continue to fund further research. All this genetic work raises issues of resource allocation which face the whole National Health Service. Can genetic screening and testing be justified if the numbers affected are very low and if we are not able to offer any treatment? How do we decide what to test for, as the known links of genes to disease multiply? Many decisions are multi-factorial; is it worth tracing the genetic base, when so many other factors come into play? Such questions affect us all and the practice of science. Science is not neutral. It shares and carries values. In a pluralist society, which values are we to adopt? Theological Perspectives The more we discover the 'stuff' of our humanity, the more some people feel we are totally determined and just like machines. It is crucial therefore to ask what it means to be human. Freedom, justice and the balance between the individual and the community reveal the need for basic human values by which we should live, do medicine and practise science. Christianity believes that telling the truth, preserving the integrity and dignity of every individual, protection of the vulnerable, providing just treatment and care for everyone and refusing to reduce human beings to materialism, but upholding an holistic view of humanity are all vital for the well being of society. Morality is too important to be left to scientists. All of us are affected and all of us ought to have a say in what science does and how it is done. If there is no moral consensus, we will be forced to develop legal guidelines to protect us all. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority and the Clothier Committee (on genetic research) are two steps in that direction. But legality is not the same as morality and we must continue to ask if such new laws and regulations are right or wrong, good or bad. 4 5