JISC UPDATE December 2010

advertisement

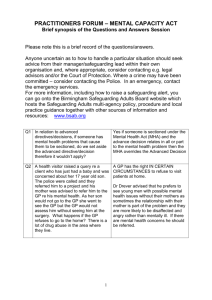

JISC UPDATE December 2010 The month kicked off with a fabulous discussion about the legal framework for medical treatment of a self-harming patient: Respondent 1: Assuming lack of capacity (e.g. citing ambivalence and the OD itself) you would treat under MCA (proportionate restraint, best interest, principle of necessity) and consider using MHA to actually detain on a medical ward for further assessment of possible mental disorder. Current MHA doesn’t actually allow treatment of a physical disorder (OD) even though it may be due to a mental disorder, although ‘legal opinion’ (but not case law) suggests that it should. Respondent 2: Agreed with above, until Louis Appleby’s letter to the RCPsych (http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/rollofhonour/rcpsychnews/january2010/applebyl etter.aspx) stating the opinion that the MHA could be used in such circumstances. However, as it is time consuming to complete a section, I think the MCA would come into play first. Respondent 3: I thought there was case law about treating a physical disorder due to a mental disorder (B v Croydon Health Authority) under Section 63 as an ancillary act if the self-harm can be categorised as the consequence or symptom of a patient's mental disorder [Jones 11th edition, Page 327]. Respondent 4: We had a case recently where the ED staff felt the patient had capacity to refuse treatment after paracetamol overdose (as per Wooltorton) and we were going to use MHA. And they recommended the following: David AS, Hotopf M, Moran P, et al. Mentally disordered or lacking capacity? Lessons for managment of serious deliberate self harm. BMJ 2010; 341: c4489. MCA vs MHA. Wollerton case.pdf Antipodean respondent 5: recommended: Ryan CJ, Callaghan S. Legal and ethical aspects of refusing medical treatment after a suicide attempt: the Wooltorton case in the Australian context. Medical Journal of Australia 2010; 193: 239-242. Respondent 6 who speaks for all of us! : ‘I always think I'm on top of this topic, until it's discussed, and then I end up feeling utterly confused’. Respondent 7: The first part of Appleby’s letter confirms that treatment for physical consequences of self harm can be treated under the MHA. But the second part of the letter states "...it is possible for someone to meet the criteria for detention under the Act even though they retain the mental capacity to take decisions about their treatment. So the need for detention under the Act is certainly one possibility to consider in the case of a patient who has seriously self-harmed as a result of mental disorder, even though they have the capacity to refuse treatment for their injuries (or have refused it by means of an advance decision). In that respect, they are no different from any other suicidal or self-harming patient." So, we are being told that life-threatening self harm is not treatable under the MHA if the patient has capacity to refuse treatment? If they have a severe enough mental illness to warrant detention, and which itself has led to severe self harm, under what circumstances are they likely to have capacity to refuse treatment? One would have to postulate that the suicidal act and the mental illness are independent events, the treatment of one having nothing to do with the other. Respondent 8: I note that usually the MCA is the first step on the algorithm, because it is usually the most pragmatic. But still, what a mess. A real Pandora’s box, this. The legal opinion I mentioned was from Lord Justice Hoffman: “It would seem strange to me if a hospital could, without the patient's consent, give him treatment directed to alleviating a psychopathic disorder showing itself in suicidal tendencies, but not without such consent be able to treat the consequences of a suicide attempt." B v Croydon Health Authority (1995) that Louis Appleby refers to in his letter actually relates to force-feeding, not the treatment of an OD. If I was asked for an opinion, I’d go for MCA to treat ± MHA to admit. Respondent 9 is a new JISC member: and helpfully writes – 1) DSH/OD/other physical problems as a direct consequence of mental illness: Possibility A: Capacity to accept/refuse physical treatment absent Treat physical health under MCA and Treat Mental health under MHA, if criteria met. Possibility B: Capacity to accept/refuse physical treatment present Option 1 - Physical treatment accepted - go ahead informally. - Treat mental health under MHA, if criteria met. Option 2 - physical treatment refused: MCA is not applicable here as capacity is present. So treat Physical health under MHA (as suggested by example of forced feeding in B v Croydon health authority AND Prof Appleby's letter referring to code of practice). But what if person does not meet criteria for detention under MHA? 2) DSH/OD/other physical problems present with but NOT a direct consequence of mental illness: Everything stays same except the fact that in possibility B option 2: Neither MCA nor MHA applicable for treatment of physical health. (Though it is unlikely to be a common occurrence because if somebody is refusing treatment of physical health problems - it is more likely to be a result/manifestation of mental illness and in that case can be treated under MHA) Respondent 10: presents 2 more scenarios: 3) DSH/OD/other physical problem, treatment refused and capacity retained (whether or not person has a mental illness) If capacity is truly retained, then we really shouldn't be treating people because a person should be allowed to make a with-capacity decision to end his or her own life. Classically the Jehovah's Witness who refuses a blood transfusion, which almost everyone will agree is a decision that should be accepted, as long as we are clear that it is definitely (or fairly definitely) a decision made with capacity. (This includes advanced directives to refuse treatment). Outside the JW situation one can imagine a situation where a person with a terminal illness and with the support of their family and with clear documentation of their choice and with no doubt about their capacity at the time of their choice presented to ED with a suicide attempt gone wrong, where one should probably respect the person's decision to decline treatment. Cases like this are incredibly rare; where capacity is retained but the person nonetheless has a mental illness, that is not interfering with their capacity (defined in a sense that means that the person was making a considered and sustained decision that life was not worth living not clouded by their mental illness - i.e. defined more tightly than a typical legal definition). The coroner felt that Wooltorton was such a case, but I suspect it was not. It would be very hard to know whether Ms W had true capacity at the time she wrote her note (not that the coroner thought that relevant) and it is almost certainly the case Ms W was intoxicated secondary to the ethylene glycol within a short period after its ingestion, likely robbing her of capacity. The other scenario worthy of consideration is: 4) DSH/OD/other physical problem, treatment refused and we are just not sure what we should be doing. In Australia the courts have been clear that they are very happy to hear these cases urgently, and can make decision under parens patriae powers. Those powers are no longer open to English courts but they can make declarations about what they think would be the legal course of action. There was a case discussion about using modafinil in chronic fatigue syndrome? All organic causes ruled out (including sleep telemetry). Patient was intolerant to antidepressants (low in mood- mainly fed up due to frustration with the fatigue, which seemed to come first), and despite psychological interventions by CFS/ME specialist nurse, was getting no better with ++ functional impairment and associated distress. A London based Liaison psychiatrist with some expertise in this area said there was no evidence base to support use of modafanil and it is not recommended by NICE for this reason (listed in the guidance under the heading "Strategies that should not be used for CFS/ME"). NICE cites blood tests that should be done & a suggestion is to manage individual symptoms (pain, insomnia etc) to try and optimise any modifiable contributory factors. March 2nd – March 4th 2011, Glasgow: The joint programme for the annual residential meetings for Faculty of Liaison Psychiatry and Faculty of Psychotherapy. The academic programme for the Faculty of Liaison Psychiatry starts on Wednesday the 2nd March 2011. Both the faculties have organized a joint day on the topic of Medically Unexplained symptoms on 3rd March 2011. Both the faculties have a separate programme for 4th March 2011. Advance notice of a meeting of the North West, N Wales and Mersey Liaison Psychiatry Special Interest Group on Friday 18th February 2011 at the Rawnsley Building, Manchester Royal Infirmary. The theme of the day is the likely impact of the new commissioning framework on Liaison Psychiatry, and what opportunities these could offer in terms of improving the provision of health care within a bio-psychosocial framework. Dr Alan Nye, Clinical Adviser Elective Care Department of Health, Associate Medical Director NHS Direct and Director Pennine MSK Partnership Ltd (an NHS ICATS organisation, which has contracted a Psychological Medicine Service from us at Oldham) will be speaking. There was grateful feedback from a clinician who presented a patient with functional dysphonia. After 2/52 on 5mg aripiprazole he is significantly better with a clear fluent voice and he has made his first telephone call in 2yrs. He says improvement was first noticed by others about 1/52 after starting treatment. I didn't sell it to him as 'the answer', and with no response to 5mg tds diazepam I think it is less likely that the mechanism of action is anxiolytic or placebo. Interestingly his abnormal gulping breathing pattern has not completely abated and physiotherapists are still helping him with breathing.. My hypothesis is that this was a secondary response to try to force speech despite motor dysfunction. An eighty four year old lady with a florid catatonic presentation admitted under the care of elderly medicine. There was no fever or haemodynamic instability. She did have auditory, visual (she is registered blind) and olfactory hallucinations and thought we were from the devil. Fortunately she responded to treatment with Lorazepam. Currently there is no hypertonia, hallucination, delusion, confusion or evidence of a dementing illness and she is euthymic. She has no past psychiatric history but is registered blind and is hypertensive. After investigation we could not determine any particular cause of this presentation. My understanding is that for a significant minority the catatonia can be idiopathic particularly in elderly women. My questions are: 1. What are the more obvious causes or differentials? 2. In the absence of any obvious reason how long should Lorazepam be continued? Jackie Gordon Worthing