Amy W - GK12

advertisement

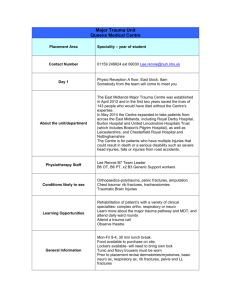

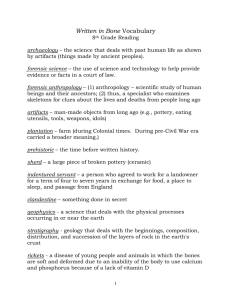

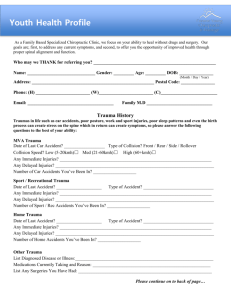

What Happened Here? Forensic Anthropology of a Medieval Mass Grave Amy W. Farnbach In this lesson, students will examine dramatic injuries on skeletons from a medieval battle. By interpreting the injuries on individuals and patterns of injuries in the skeletons as a group, students will use techniques similar to those used by forensic anthropologists investigating realworld crime scenes and archaeological sites. Keywords forensics; skeleton; crime scene Grade Level 8, but also appropriate for older students Duration 1.5 Class periods Purpose This lesson is intended to introduce students to the application of anthropological knowledge about the human skeleton to answer questions of interest to the legal system. In this lesson, students interpret photographs from the excavation of a mass grave, which they later learn contains victims of the medieval Battle of Towton in England’s Wars of the Roses. Placing this lesson in the context of a historical battle both offers students conceptual distance from material they may find disturbing and helps students to gain an awareness of the broad utility of forensic science, which they are likely to associate with modern crime dramas. The lesson addresses both national and Arizona science standards for the eighth grade. Although it chiefly addresses Arizona standards in Strands 1 and 2, it can serve as an interest-grabbing end-of-year or poststandardized-testing “reward”. Standards NATIONAL SCIENCE EDUCATION STANDARDS Content Standards: 5 – 8 Content Standard A Abilities necessary to do scientific inquiry; understandings about scientific inquiry Content Standard C Structure and function in living systems; regulation and behavior Content Standard F Personal health; science and technology in society Content Standard G Science as a human endeavor; nature of science ARIZONA STATE STANDARDS Eighth Grade Strand 1: Inquiry Process Concept 1: Observations, Questions, and Hypotheses PO 3. Generate a hypothesis that can be tested. Concept 3: Analysis and Conclusions PO 1. Analyze data obtained in a scientific investigation to identify trends. PO 2. Form a logical argument about a correlation between variables or sequence of events. PO 5. Explain how evidence supports the validity and reliability of a conclusion. Concept 4: Communication PO 1. Communicate the results of an investigation. PO 3. Present analyses and conclusions in clear, concise formats. PO 4. Write clear, step-by-step instructions for conducting investigations or operating equipment (without the use of personal pronouns). PO 5. Communicate the results and conclusion of the investigation. Strand 2: History and Nature of Science Concept 1: History of Science as a Human Endeavor PO 4. Evaluate career opportunities related to life and physical sciences. Strand 5: Physical Science Concept 1: Properties and Changes of Properties in Matter PO 7. Investigate how the transfer of energy can affect the physical and chemical properties of matter. Background Teachers should read through all teacher packets, particularly the background reading (excerpts from Fiorato, Boylston, and Knüsel 2000). Teachers who do not feel confident in their understanding of forensic anthropology techniques for estimating age, sex, ancestry, and height from skeletons and interpreting skeletal trauma can gain a basic background from material presented in the introductory online activity (the National Library of Medicine’s “Anthropological Views” at Visible Proofs, linked in Procedures below) and in other sources linked in Resources below. To interpret the photographs included in this lesson, students will need a basic idea of the human skeleton’s normal appearance, particularly the skull. This can be provided with a classroom model of the skeleton or images viewed in class from a source such as the eSkeletons Project (link in Resources below); in rooms with computer projection capability, the skull from the latter can simply be projected for students’ reference during the activity. Materials Teacher PDF packets Excerpts from Fiorato, Boylston, and Knüsel (2000) describing the Battle of Towton (Chapter 2: FioratoCh2.pdf) and the associated skeletal trauma (Chapter 8: FioratoCh8.pdf), as well as answer keys to all student packets (GraveKey.pdf, TraumaKey.pdf, PatternsKey.pdf). Student PDF packets “What happened here?” (Grave.pdf) “How were they injured?” (Trauma.pdf) and “What do the patterns tell us?” (Patterns.pdf) as well as “Now, show what you’ve learned!” (Show.pdf) Procedures OVERVIEW Students will examine photographs from the archaeological excavation of a mass grave of men killed during the Battle of Towton (AD 1461) in Great Britain’s Wars of the Roses (AD 1455 – 1487) to interpret the skeletal trauma, including timing, cause, and patterning of injuries. PRIOR TO THE LESSON 1. This lesson deals with violent material that may upset some students. If necessary, notes or release forms should be sent home prior to the lesson. 2. Some cultural groups prohibit viewing human remains, even in photographic form. Students whose beliefs do not allow them to view the photographs of skeletons should be allowed to perform an alternate activity, perhaps having to do with another aspect of forensic science. 3. Reproduce all necessary copies of student and teacher PDF packets. One copy of each student packet per group of four is recommended (i.e., for 24 students, produce 6 copies of each packet). 2 VOCABULARY Skull The skull consists of the cranium and mandible (lower jaw). Cranium The cranium comprises the bones of the braincase and face, except for the mandible. Ancestry In forensic anthropology, an individual’s ancestry can be estimated in some cases from features of the skull, and may be broadly classified as “Caucasoid” (European or Middle Eastern ancestry), “Mongoloid” (Asian or Native American ancestry), or “Negroid” (African ancestry). These old and negatively laden terms are unfortunately still encountered. Cause of death The cause of death is the injury or disorder that resulted in death, such as asphyxiation, stroke, or cancer. Manner of death The manner of death pertains to the context of the death, and falls into five categories: natural, accidental, suicide, homicide, or undetermined. Trauma In forensic anthropology, an injury. Blunt trauma This type of trauma is caused by contact with a blunt object. This can result from being hit with a blunt weapon, or from contact with parts of the assailant’s body (e.g., fists, feet, knees) or with the ground. Sharp trauma As you might expect, this type of trauma is caused by contact with a sharp object. Puncture wound This type of trauma is deeper than it is wide, and for the purposes of this activity can be used to describe relatively small and neat-edged perforations in the cranium. Antemortem Antemortem injuries occur noticeably before the time of death, and show signs of healing. Perimortem Perimortem injuries occur close to the time of death, and can be significant to estimating the cause and manner of death. Postmortem Postmortem injuries occur noticeably after the time of death, and for the purposes of this activity can be identified by the light color of their broken surfaces, indicating that the broken surfaces have not been exposed to the environment as long as adjacent bone. DAY 1 (Partial class period) Pre-assessment (5 minutes) Briefly discuss as a class the use of skeletal remains in forensic contexts. Students will probably know that injuries on the remains can be used to determine cause and manner of death, and may know about the use of dental records to identify the deceased. They may be surprised to learn that an individual’s sex, age, ancestry, and height can also be estimated from the skeleton. Introductory Activity (15 minutes) Have students complete the “Anthropological Views” activity from the National Library of Medicine’s Visible Proofs resources, or another activity that briefly introduces them to the basics of forensic anthropology: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/visibleproofs/education/anthropological/index.html 3 DAY 2 (Full class period) Forensic Anthropology (40 minutes) Provide each group of students with packets “What happened here?” “How were they injured?” and “What do the patterns tell us?” Do not offer background information about the Battle of Towton, or even about the age of the burials or their location. Ask the students to answer the questions on the first page of each packet thoughtfully and as thoroughly as they can. Where they do not know the answer from the information available, they should provide a suggestion of information that would help them to answer (e.g., “We cannot tell what sex these individuals are from this picture; a closer picture of the skull or pelvis is needed.”). “What happened here?” asks students to make initial assessments of the number of individuals buried at this site, who they are, and how they came to be buried there. “How were they injured?” asks students to examine individuals and assess whether injuries occurred antemortem, perimortem, or postmortem; sort the injuries into types; and draw the weapon that caused the injury. Students will likely need some scaffolding to figure out that antemortem injuries show signs of healing, while postmortem injuries show a fresh edge that has not been exposed to the burial environment as long as adjacent bone. If possible, allow students to sort the injuries before providing them with the categories sharp force, blunt force, and puncture; it is likely that they will sort them correctly by appearance, and you can provide them with the terminology as they do so or after. “What do the patterns tell us?” asks students to examine composites of each injury type; that is, every sharp force trauma observed in the Towton mass grave was drawn onto a single skull to search for patterning. Students will probably readily notice the patterns, but may require scaffolding to answer why such patterns are present. Closing Discussion (20 minutes) Discuss students’ answers as a group, encouraging students toward the correct answers if they have not already identified these. Close with discussion of the answers to “What happened here?”, as these may be more answerable after discussing the other packets. It may be useful to bring in external resources. For example, many students may assume the puncture wounds or dramatic blunt force injuries are gunshot wounds; show (or ask the students to find) gunshot wounds in the cranium for comparison to encourage the students to think of other explanations. Students may ask why only injuries on the skulls are shown; in this grave, every cranium had trauma, whereas postcranial (the neck, torso, arms, and legs) trauma was rarer. Discuss with students why this may be: Fiorato, Boylston, and Knüsel (2000) argue that either postcranial trauma did not affect the bone as often, or the postcranial skeleton was protected by clothing or armor. FOLLOW UP Post-assessment Following the activity, the summative evaluation (“Now, show what you’ve learned!”) should be given either as an independent assessment or as part of a unit exam. Assessment FORMATIVE EVALUATION Pre-assessment of students’ background, misconceptions, and interests with respect to forensic anthropology before the activity can be achieved through a brief class discussion of skeletal remains as portrayed on popular TV shows such as Bones and CSI. 4 Post-assessment of students’ understanding of forensic anthropology is included in the summative evaluation below as the short essay question, “Describe one piece of information you can learn from a skeleton. Explain step by step how you would get this information, and how law enforcement officials might use it to solve a crime.” SUMMATIVE EVALUATION Ask students to apply what they’ve learned about skeletal trauma using the PDF packet “Now, show what you’ve learned!” Resources The eSkeletons Project Forensic Anthropology Human Bones Sex Determination Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body Websites on the Wars of the Roses: www.luminarium.org/encyclopedia/warsoftheroses.htm www.wars-of-the-roses.com/index.htm http://www.warsoftheroses.com What We Do Work Cited Fiorato V, Boylston A, Knüsel C, eds. 2000. Blood Red Roses: The Archaeology of a Mass Grave From the Battle of Towton AD 1461. Oxford: Oxbow Books. 5