Spanish Subjunctive Mood: One Form, More than One Meaning

advertisement

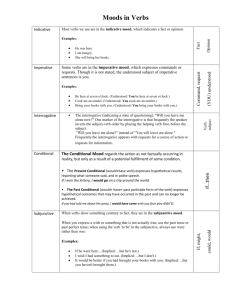

Spanish subjunctive mood: One form, more than one meaning? Bob DE JONGE University of Groningen 0. Introduction1 In this contribution I will argue, as others have done before me (cf. for instance Klein 1975), that the various phenomena related to the distribution of the subjunctive and the indicative mood in Spanish may be explained by the assumption that the indicative and subjunctive each have one single semantic meaning. The proposed hypothesis has the advantage that it may offer a general explanation for the occurrences of both forms and does not have to resort to various description-like meanings for the occurrences of the subjunctive in different circumstances. The hypothesis about the meaning of the mood distinction presented in this study, is non-arbitrary in the sense that it is not only capable of explaining the distribution of the subjunctive vs. indicative forms, but also serves to justify it. Notice that if the assumption that one central meaning can justify and predict the distribution of subjunctive and indicative forms in Spanish is correct, this provides support to the general idea that all individual and unique meanings of all linguistic forms 2 could, and in my view, should be taken as responsible for linguistic structure as a whole.3 Before presenting the hypothesis that will be examined here, some of the the most important meanings that have been proposed for the subjunctive mood will be briefly reviewed.4 1 I am indebted to the editors of this volume and Co Vet for comments on earlier versions of this paper, and to Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen for its original outline. All remaining flaws and errors are my own responsibility. 2 'Linguistic forms' should be taken in the broadest possible sense: also syntactic phenomena may be considered, in my view, as linguistic and thus meaningful forms; cf. for instance Bolinger (1991) for the meaning of word order in Spanish. 3 For a more detailed discussion on this theoretic point of view, see García (1975, especially chapter X), Diver (1975 and 1995), Reid (1991) and Contini-Morava (1995). 4 I am well aware of the fact that the literature on mood in Romance linguistics is abundant. However, due to space limitations I will limit myself to two studies that work with hypotheses comparable with the one presented here. 80 1. Bob de Jonge Some previous studies Klein (1975), who bases herself on Hooper (1975) and Terrel and Hooper (1974), tries to demonstrate that the indicative mood indicates 'assertion' of the occurrence expressed by the verb, and that the subjunctive indicates' non-assertion' in complement clauses (Klein 1975:353). However, there are some problematic cases, as shown by (1), taken from Klein (1975:355): (1) Lamento que aprenda (S) 'I regret that he should learn' [Klein's translation] In Klein's view, with 'main verbs of comment, such as lamentar 'regret' [...] the non-assertion of the complement can only be taken to indicate that it is not the purpose of the sentence to state this fact, but only to comment on it [...].' This is essentially circular: the reasoning that the meaning of the subjunctive mood is non-assertion, and that aprenda cannot be taken as an assertion, in spite of its factuality in the real-world-situation, is only valid because of the assumption that the subjunctive mood means just that. Moreover, if the subjunctive mood is triggered by the verb lamentar, whose purpose is to comment on aprender, and not to assert it, then other predicates which also comment on the subordinate clause should behave in the same way. That this is not the case is shown by (2): (2) Es evidente que aprende (I) 'It is obvious that he is learning' There are, at least, two observations to be made: in the first place, it might be objected that que aprende here is a subject clause that may therefore behave differently, and in the second place, es evidente indicates a comment on a factual occurrence. However, the first potential solution would introduce arbitrariness in the analysis, while we intended to let meaning determine the distribution, and the second observation is incompatible with the explanation of (1): if the fact that the predicate of the main clause expresses a comment -any comment- on the content of the subordinate clause triggers subjunctive mood, it should always do so, and not only in the casse of comments in certain constructions, at least, if we are to take meaning seriously. As I have said in the beginning, it is my intention to do so. Other important studies that focus on meaning related to subjunctive mood, like Haverkate 1989, have a similar way of reasoning as Klein 1975. Haverkate assumes that one of the fundamental functions of the subjunctive mood is affirming that the sentence with the verb in subjunctive mood does not convey information (1989:98), but should be taken as expressing something that is already conceived, explicitly or not, in the previous context. The occurrence in subjunctive would then indicate background information. Spanish subjunctive mood 81 But here again, cases like (2) are problematic, since the preconception of the information is as essential for this kind of sentences as for those selected by other predicates, such as the one in (1). Moreover, the meaning postulated by Haverkate is of a negative nature. Intuitively, this is not very likely to be the case for a linguistic sign: if the subjunctive expresses that the sentence does not convey (new) information, the question rises what the subordinate part in the subjunctive does convey. It is not the comment in itself, for that is rendered in the main clause of the sentence. We should, then, look for a meaning of the subjunctive that can be stated in positive terms in order to be able to explain (and not merely describe) all its uses as opposed to those of the indicative. 2. Hypothesis It should be stressed that neither of the two moods necessarily conveys the truth about the real world and that neither has more truth-value than the other. Speakers express, by definition, a vision on reality that is subjective and can only be taken as the version of reality he or she wants to get across to the hearer. The best proof of this is lying: all speakers are capable of lying, and I believe I am not saying anything absurd if I state that most lying will take place in the indicative mood. Thus, occurrences expressed in the indicative mood are not necessarily factual, but the effect on the hearer is intended to make him or her believe they are. The meaning assertion for indicative mood is therefore not badly chosen; it is non-assertion that needs refinement. What examples as (1) and (3) below have in common, is that in both sentences, another situation is relevant apart from the one expressed by the subjunctive mood: (3) Quiero que aprenda (S) 'I want that he/she learns' In (1), the speaker has in mind a situation that is different from the actually presented one, namely a situation in which the person he or she is talking about is not learing, as opposed to what he or she is actually doing. In (3), it is just the other way round: the person in question is not learning, and the speaker is expressing his or her wish that the other should do so. If this correspondence is the core of the meaning of the subjunctive mood, then we can hypothesize that both moods have the following meanings: (4) Indicative mood (I) = assertion of the occurrence expressed by the verb 82 (5) Bob de Jonge Subjunctive mood (S) = contextual relevance of an alternative for the occurrence expressed by the verb An important difference between this hypothesis and others is that it takes into consideration the communicative situation in which the studied utterances in the subjunctive mood occur. In order to test a hypothesis about a meaning, it is, in my view, necessary to take into account the communicative effects of this meaning on the message. Therefore, use of terms like contextual and relevance are indispensable for this kind of hypotheses. Below, I will briefly discuss the role and importance of these terms for the analysis I will present further on. As shown in De Jonge (1999), the proposed hypothesis should account for cases like (3), in which use of the subjunctive is said to be 'governed' by the verb querer. In an approach in which one basic meaning is held to be responsible for all occurrences of the subjunctive, syntactically governed cases should be dealt with in a non-arbitrary way, and not by resorting to rules that describe the co-occurrence of certain types of verbs and the subjunctive. These verbs should have a meaningful characteristic in common that explains use of the subjunctive. This characteristic could very well be the fact that in all communicative situations in which querer que 'to want to' occurs, the desired occurrence is actually not taking place. If this is so, in situations in which a verb of desire is used, use of the subjunctive should then indicate this current relevance of the opposite situation, the most logical alternative, in the given context. Since with all verbs of desire an alternative is relevant, categorical use of the subjunctive should not surprise us. De Jonge (1999) demonstrates the qualitative validity of this reasoning for verbs of desire, emotive predicates and hacer que 'to make that' in the matrix clause and with conjunctions like aunque 'although'5 and el hecho de que 'the fact that'. Before starting with the actual analysis, it is important to set the rules for it. In the first place, by 'alternative', I mean an alternative to the verb in the subjunctive. The most common alternative to a verb is its negated counterpart. Therefore, when considering possible alternatives to the verb under analysis, the negation of the verb is always taken into consideration. However, negations implied in subordinate conjunctions as in sin que 'without 5 Subordinate clauses with aunque may either occur in the subjunctive or in the indicative. Here too, the proposed hypothesis explains this distribution in a sentence like aunque hace/haga mal tiempo, vamos a la playa 'although/even if the weather is bad, we will go to the beach'. The second option takes into account the possibility of bad wheater, presupposing the alternative, namely good weather, the normal situation for beach visits. The first option, on the other hand, merely takes good weather as an observed fact. Spanish subjunctive mood 83 that' are not, since it is precisely the meaning of these conjunctions that may explain the relevance of an alternative. 6 It should also be stressed that the word 'relevance' is crucial for the proposed hypothesis. For any given situation it is possible to think of an alternative one, but this alternative situation is not necessarily relevant in the given context. In analyses of categorical uses of the subjunctive, it is possible to test the proposed hypothesis on the basis of the meaning of the relevant syntactic element, as shown above and in De Jonge (1999). However, it is impossible to do so in those cases where there is variation between subjunctive and indicative, for only analysis of the wider context can demonstrate the RELEVANCE of an alternative. In this paper, the hypothesis will be submitted to a test based on a corpus of independent examples in syntactic contexts where variation between subjunctive and indicative is observed, taken from a collection of short stories by García Márquez (García Márquez 1994). In order to demonstrate the correctness of the proposed hypothesis for the meaning of the subjunctive, the relevance of the alternative will be studied in the communicative setting of each of its occurrences. 3. The data In order to investigate the hypothesis systematically, a corpus of examples of both indicative and subjunctive mood in similar contexts has been collected. For this investigation the largest group of contexts in which both moods occur was selected, namely all clauses introduced by some form of the conjunction que 'that'. All instances of these clauses were taken from García Márquez (1994), in total 727 introduced by some form of que, of which 611 (84%) were in the indicative, and 116 (16%) in the subjunctive mood. Table 1 presents the distribution of both moods in different kinds of clauses introduced by que. One thing is clear from table 1: practically all clause types show both indicative and subjunctive mood, so it is safe to say that there is no relation between syntactic categories and use of mood in Spanish. Within these categories, however, there are some groups of examples that show exclusive use of the subjunctive in the subordinate clause, while other groups exclusively show the indicative mood. The next step in the analysis is to show 6 This reasoning may seem circular, but in fact it is not. In the search for an alternative, only the verb in the subjunctive is taken into consideration, eventually with its negation, which has a fixed position in relation to the verb. Its relevance is to be found in the rest of the context, which is not fixed. Some subordinate conjunctions, such as para que (cf. De Jonge 1999) and sin que trigger this contextual relevance through their general meaning, and so no further context needs to be taken in consideration. 84 Bob de Jonge whether the postulated hypothesis is capable of explaining the mood distribution within each of these categories. Table 1: Distribution of indicative vs. subjunctive mood in subordinate clauses introduced by (x)que, in García Márquez 1994 indicative mood subjunctive mood Total complement clauses 140/81% 33/19% Total (X) prep.que 93/67% 46/33% Subject clauses 32/67% 16/33% Relative clauses 284/95% 15/5% Total (X) adj. que 19/95% 1/5% Adv.que 16/89% 2/11% Total prep.N que 17/100% -Imperative que 1/50% 1/50% sino que 2/100% -#Que 7/78% 2/22% Total 611/84% 116/16% For reasons of space limitations we will not be able to discuss all examples and all categories. Therefore, we will select a number of representative groups and minimal pairs in order to submit the hypothesis to the most severe test possible. 7 4. Complement clauses Table 2 contains the different groups of complement clauses with indicative and subjunctive mood. Some predicates trigger exclusive use of the subjunctive or indicative, just as each and every grammar. For example, in sentences with querer que 'to want that', we always find subjunctive mood in the complement clause. This should not surprise us in the light of the postulated hypothesis, since the main verb is normally uttered in a situation in which the occurrence of the complement clause has not (yet) taken place. Thus, since verbs of desire are only and exclusively used in situations where the desired occurrence is not taking place, there is always a relevant alternative -the actual state of affairs-, which explains the overall presence of the subjunctive mood.8 7 The pairs given in this paper are not minimal in the sense that there is only one observable difference between the two members, namely use of indicative or subjunctive mood alone. The pairs presented here share a number of features, but are also (and necessarily so) different in other aspects. It is precisely these aspects that permit us to detect the relevance of the alternative in one of the examples, and the absence of it in the other. The use of the word 'minimal' is therefore omitted from here onwards; the presented pairs should be taken as 'as minimal as possible, given the corpus under analysis'. 8 There are cases that seem to contradict this reasoning, as Quiero que continúes (S) así 'I want you to go (S) on like this'. In fact, also here there is an alternative relevant: the speaker is presupposing or has reason to assume that the addressee may stop his activities. Spanish subjunctive mood 85 Things become more interesting when we study the groups of examples in which both moods occur. One of these consists of complement clauses with decir que 'to say that' in the matrix clause. As can also be inferred from Vet (1996:144-145), who presents a structural analysis, there is no reason to assume that there is more than one meaning for decir que in order to account for the fact that both moods occur with it. This would be a circular way of reasoning. We therefore assume that with verbs of saying the difference in meaning is uniquely due to the meaning of the moods. In (6) and (7) we offer a pair that illustrates this: Table 2: Distribution of indicative vs. subjunctive mood in complement clauses in different matrix clauses, in García Márquez 1994 decir que pensar/creer que no pensar/creer que esperar que ruego/mandato que saber que no saber que imaginar que ver/sentir, etc. que no ver/sentir etc. que recordar que no recordar que suponer que comprender que jurar que querer que permitir que agradecer que indicar que tener en cuenta que buscar que soñar que prometer que Total compl. cl. indicative mood 31 34 1 --13 2 3 27 2 4 -1 12 5 ---2 1 -1 1 140/81% subjunctive mood 5 -3 6 11 ------1 1 --3 1 1 --1 --33/19% (6) -Baltazar -dijo Montiel, suavemente-. Ya te dije que te la lleves (S). '-Baltazar -said Montiel, softly-. I already told you that you should take (S) it with you.' (GGM 1994:78) (7) -¿Entonces? Ana se arrodilló frente a la cama. -Que además de ladrón eres embustero -dijo. -¿Por qué? -Porque me dijiste que no había (I) nada en la gaveta. 'And so? Ana knelt down in front of the bed. 86 Bob de Jonge -That apart from a thief, you are also a cheater -she said. -Why? -Because you said to me that there was (I) nothing in the drawer.' (GGM 1994:35-6) In (6), Baltazar, a carpenter who made a birdcage for Montiel's son without Montiel knowing it, refuses to take the cage with him and finally gives it to the boy. Not taking it away is therefore an alternative and Baltazar's refusal to do so indicates its relevance in the given context. This corresponds, as expected, to the used subjunctive form. In (7), on the other hand, Ana claims that Dámaso, who has stolen a set of French snooker balls from a bar, has lied to her about the amount of money he is supposed to have found in the drawer of the bar. She is reporting his uttered words (that in the end turn out to be true) and since an assertion was made, there is no relevance for an alternative, in spite of the fact that Ana believes Dámaso is lying: she is asserting his alleged lies. Although these cases fit well in the proposed hypothesis, it could be objected that they are special, since they represent reported speech, and that (6) is a reported imperative. There are historical relations between the imperative and the subjunctive mood -it is not difficult to link the function of the imperative to the proposed meaning of the subjunctive mood. However, I will not dwell on this matter any further, due to space limitations, but instead, another pair that does not exhibit reported speech will be discussed. In (8) and (9), we find two instances of no pensar que in the main clause, with indicative in (8) and subjunctive in (9): (8) No pensó -como no lo había pensado la primera vez- que Dámaso estaba (I) aún frente al cuarto, diciéndose que el plan había fracasado, y en espera de que ella saliera dando gritos. 'She did not think -as she had not thought the first time- that Dámaso was (I) still standing outside the door, telling himself that the plan had failed and waiting for her to come out screaming.' (GGM 1994:63) (9) A nadie se le había ocurrido pensar que la Mamá Grande fuera (S) mortal, salvo a los miembros de su tribu, y a ella misma, aguijoneada por las premoniciones seniles del padre Antonio Isabel. 'It never crossed anybody's mind that la Mamá Grande was (S) mortal, except for the members of her tribe, and herself, stimulated by the senile warnings of Father Antonio Isabel.' (GGM 1994:145) In (8), Ana is waiting for Dámaso, who has left to return the balls to the bar, because the owner of the bar is practically ruined and Dámaso is unable to sell them to anybody. In this example, a description is given of a thought she did not have on the first occasion, when Dámaso left in order to steal them, and that she is not having now. In (9), on the other hand, the alternative, namely that la Mamá Grande, the most important and richest woman in Spanish subjunctive mood 87 the village, would not be mortal, is clearly relevant: most of the people of the village had acted as if she were not and had not taken any precaution. In (10) and (11), another interesting pair is given, with suponer que 'to suppose that' as the main clause verb: (10) -Bueno -dijo sin levantar la cabeza-. Y suponiendo que así sea (S): ¿qué tiene eso de particular? '-All right -she said, without raising her head-. And supposing that it were (S) so: what is so special about that?' (GGM 1994:138) (11) Adormilado en el corredor del hotel, entorpecido por el bochorno, no se había detenido a pensar en la gravedad de su situación. Suponía que el percance quedaría (I) resuelto al día siguiente con el regreso del tren, de suerte que ahora su única preocupación era esperar el domingo para reanudar el viaje y no acordarse jamás de ese pueblo donde hacía un calor insoportable. 'He had fallen asleep in the hallway of the hotel, lethargic because of the warm wind and had not realized the seriousness of his situation. He supposed that his bad luck would (I) be over the next day when the train returned, so that the only thing to do was to wait until Sunday when he could continue his journey and forget about this village where it was unbearably hot.' (GGM 1994:119) In (10), the speaker's grandmother reproaches her with passing the night writing letters. By saying 'supposing it were so', she is claiming that she did not; the subjunctive mood –according to its supposed meaning- indicates that an alternative -it is not so- is relevant. In (11), on the other hand, the uttered supposition is expected to take place: the person of the fragment has lost his train and supposes he will be able to take the next one the next day, a perfectly normal thought, induced by the train-table. After having examined a number of pairs that fit into the proposed theory and that give reason to assume that within this syntactic category the theory provides a plausible explanation for mood alteration in complement clauses, we will now pass on to another grammatical category where there is variation in the use of subjunctive and indicative mood, namely relative clauses. We will ingestigate if here too we find evidence for the correctness of the proposed meaning. 5. Relative clauses Table 3 contains the distribution of subjunctive and indicative mood over different types of relative clauses: 88 Bob de Jonge Table 3: Distribution of indicative vs. subjunctive mood in different types of relative clauses, in García Márquez 1994 definite antecedent indefinite antecedent lo (x) que def.ant.más adj.que neg.antecedent algo/alguien que Relative clauses indicative mood 186/97% 68/96% 24 2 -4 284/95% subjunctive mood 6/3% 3/2% 1 2 2 1 15/5% It is clear from this table that there is a great preference for the indicative mood in relative clauses. Therefore, it is even more interesting to study the small amount of cases in which a Subjuntive is used. In (12) and (13) the antecedent is indicated by the definite article –el en (12) and los in (13)alone: (12) -Pobre hombre -suspiró Ana. -Pobre por qué -protestó Dámaso, excitado-. ¿Quisieras entonces que fuera yo el que estuviera (S) en el cepo? 'Poor man -Ana sighed. -Why poor -protested Dámaso, excited-. Did you want me to be the one who is (S) in jail?' (GGM 1994:39-40) (13) -Los que vienen (I) aquí ruedan una silla para el corredor que es más fresco -dijo la muchacha. '-The people that come (I) here move a chair to the hall-way because it is cooler said the girl.' (GGM 1994:114) In (13), the people that do not come there -the same hot place as indicated in (11)- do not have anything to do with this context, so they do not have any relevance and an indicative is used. In (12), on the contrary, Dámaso is speaking about an alternative situation: he himself is not in jail, but someone else, falsely accused of the robbery he committed (see also (7) and (8)). The relevance of this alternative situation, again, justifies the use of the subjunctive mood in this example. It is interesting to note that traditional grammars state the importance of the acquaintance with the antecedent in relation to the used form. According to these grammars, the use of the definite article can be taken as an independent indication of acquaintance with the antecedent, implicit or explicit, and trigger use of the indicative. An indefinite article or its absence would indicate that the antecedent is unknown, which, in its turn, should lead to the subjunctive. One would expect, then, that antecedents preceded by the definite article would show a preference for the indicative mood, and the Spanish subjunctive mood 89 antecedents preceded by the indefinite article for the subjunctive mood. However, table 3 shows that quantitatively speaking, there is no significant difference between the two groups. Qualitatively speaking, the next pair, with antecedents preceded with the indefinite article, again shows that the proposed hypothesis is capable of explaining both forms in their respective contexts (cf. (14) and (15)): (14) A pocas cuadras de allí, en una casa atiborrada de arneses donde nunca se había sentido un olor que no se pudiera (S) vender, permanecía indiferente a la novedad de la jaula. 'Only a few blocks away, in a house filled with harnesses where never anything had given a smell that could (S) not be sold, he [Montiel] remained indifferent to the novelty of the cage.' (GGM 1994:74-5) (15) Después de que el alcalde les perforaba las puertas a tiros y les ponía el plazo para abandonar el pueblo, José Montiel les compraba sus tierras y ganados por un precio que él mismo se encargaba (I) de fijar. 'After the mayor perforated their doors with gunshots and gave them a deadline for leaving the village, José Montiel bought their land and cattle for a price he fixed (I) himself.' (GGM 1994:89-90) In both cases the antecedent is inanimate and unknown in the previous context, as indicated by the indefinite article. Nevertheless, in one case the subjunctive is used and in the other, the indicative. The hypothesis proposed in this article again serves perfectly to explain these two cases: (15) presents a description of how people were expelled from the village and how Montiel bought their properties and fixed the prices. There is no relevant alternative present in the context, so an indicative form is used. In (14), on the contrary, the context implies that anything that had a smell in that house could be sold.9 This is an alternative to the expression in the fragment and therefore the subjunctive is used here. Another remarkable result that can be drawn from table 3 is the fact that relative clauses with lo as an antecedent mostly take the indicative mood, with only one exception within a total of 25 examples. This single case of subjunctive is given in (16); (17) offers a similar context with the indicative: 9 In syntactic and traditional analyses, the negation nunca 'never' in the matrix is said to provoke use of the subjunctive in the subordinate clause (cf. for instance Kampers-Manhe (1991:49) for French and Quer (1998:37) for Catalan). However, as stated above in general terms, this observation does not explain its appearance in these contexts, whereas the proposed hypothesis justifies why the subjunctive is the most coherent choice: a negation of this kind automatically implies the relevance of an alternative one. 90 Bob de Jonge (16) Si usted quiere, llévese lo que le haga (S) falta y déjeme morir tranquila. 'If you want, take whatever you need (S) and let me die in peace.' (GGM 1994:91) (17) Cuando tuvo las cosas dispuestas sobre la mesa, rodó la fresa hacia el sillón de resortes y se sentó a pulir la dentadura postiza. Parecía no pensar en lo que hacía (I), pero trabajaba con obstinación, pedaleando en la fresa incluso cuando no se servía de ella. 'When he had everthing on the table, he moved the drill towards the chair and sat down to polish the denture. He seemed not to think about what he was doing (I), but he was working fanatically, pedalling on the drill even when he did not use it.' (GGM 1994:21-2) In (16), Montiel's widow tells the person who is helping her to settle Montiel's affairs shortly after his death to leave and take whatever he may want. Of course there are many alternatives among the things he might want to take –and if he is polite, he does not take anything- and the use of the subjunctive indicates that there are no restrictions in his choice. In (17), on the other hand, we see a description of a dentist preparing his tools and working with them. Since it is a normal description of what he is doing, no possible alternative is relevant in this particular fragment, so an indicative mood is used. The pair in (18) and (19), finally, is very interesting, Out of any context, the indicative as well as the subjunctive mood may be used in cases such as these, with a superlative antecedent. However, the way both forms are used in these particular contexts confirms the postulated hypothesis: (18) Hasta cuando cumplió los 70, la Mamá Grande celebró su cumpleaños con las ferias más prolongadas y tumultuosas de que se tenga (S) memoria. 'Even when she was 70, Mamá Grande celebrated her birthday with the longest and most tumultuous fancy fair that people remember (S).' (GGM 1994:146-7) (19) -Es el alambre más resistente que se puede (I) encontrar, y cada juntura está soldada por dentro y por fuera -dijo. '-It is the strongest wire that can (I) be found, and every joint is solded on the in and the outside -he said.' (GGM 1994:73) The main difference between (18) and (19) is that (18) presents an almost hyperbolic description of the importance and richness of Mamá Grande, whereas in (19), Baltazar is merely describing the cage he has just finished (see also (6)). Baltazar does not do so in a boasting way, for the cage has already been sold and therefore, there is no need to do so. The fact that there is no alternative relevant in (19) only stresses Baltazar's modesty: he is merely describing what he has just made and which materials he has used. The use of the subjunctive in (18), on the other hand, has the effect of Spanish subjunctive mood 91 stressing the length and tumult of the fancy fair. According to our hypothesis, this is so because the subjunctive indicates implicitly that a longer and more tumultuous fancy fair is not remembered. Therefore, use of the subjunctive is more appropriate in (18) than in (19) and the indicative more in (19) than in (18). 6. Conclusion I have tried to show in this article that a theory that parts from the meaning of the linguistic sign is not only capable of describing, but also of explaining the distribution of linguistic forms, and thus provides parts of the linguistic structure as a whole. Although we have not discussed meaning and use of subjunctive vs. indicative mood in all possible contexts, the results of the investigation presented here are, in my view, promising. The data from my corpus showed that a classification according to traditional syntactic constructions does not offer a satisfactory explanation for the use of both forms, because in all constructions both forms occur without clear preference for either one of them. Thus, no cause and effect relation could be established between form and syntactic construction. Only more detailed study of subcategories did reveal some correlations. These had to do with coherent relations in meaning between the main clause verb and the subjunctive mood rather than the syntactical construction, as we have seen, for instance, in the case of querer que + subjunctive mood. More interesting, however, were the cases in which variation was observed, as in the complement of decir and in relative clauses with a superlative antecedent. In those cases the proposed meaning provides an explanation for the occurrence of both forms in the given contexts. It should be stressed that these results were obtained by investigating the sentence in its broader context; the relevance of an alternative can only be demonstrated by taking into consideration the communicative setting. Of course, this is not the last word to be spoken on this matter. Other constructions that were not discussed here, such as conditional and temporal clauses, also need to be examined. The results obtained so far give reason to be optimistic about the next episode of this project. References Bolinger, D. (1991). Meaningful word order in Spanish. In: Essays on Spanish: Words and grammar. Newark, Delaware: Juan de la Cuesta, 218-230. 92 Bob de Jonge Contini-Morava, E. (1995). Introduction: On linguistic sign theory. In: E. Contini-Morava and B. Sussman Goldberg (eds.), Meaning as explanation.. Advances in linguistic sign theory. Trends in Linguistics, Studies and Monographs 84. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 1-39. Diver, W. (1975). Introduction. In Columbia University Working Papers in Linguistics 2. 1-26. Diver, W. (1995). Theory. In: Ellen Contini-Morava and Barbara Sussman Goldberg (eds.), Meaning as explanation. Advances in linguistic sign theory. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 43-114. García, E.C. (1975). The role of theory in linguistic analysis: the Spanish pronoun system. Amsterdam: North Holland. García Márquez, G. (1994). Los funerales de la mamá grande. Barcelona: Plaza & Janes. Haverkate, W.H. (1989). Modale vormen van het Spaanse werkwoord. Dordrecht: Foris. Hooper, J. (1975). On assertive predicates. In: J.P. Kimball (ed.), Syntax and Semantics 4. New York/London: Academic Press, 91-124. De Jonge, R. (1999). El uso del subjuntivo: ¿un problema para los hablantes de lenugas germánicas? In: F. Sierra Martínez et al. (eds), Las lenguas en la Europa comunitaria, proceedings from the 3rd International Colloquium, Amsterdam 1997. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 75-84. Kampers-Manhe, B. (1991). L'opposition subjonctif/indicatif dans les relatives, PhD thesis, University of Groningen. Klein, F. (1975). Pragmatic constraints on distribution: the Spanish subjunctive. Papers from the regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society XI, 353-365. Quer, J. (1998). Mood at the interface. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics. Reid, W. (1991). Verb & noun number in English: A functional explanation. London and New York: Longman. Terrell, T. and J. Hooper (1974). A semantically based analysis of mood in Spanish. Hispania 57, 484-494. Vet, J.P. (1996). Analyse syntaxique de quelques emplois du subjonctif dans les complétives. Cahiers de Grammaire 21, 135-152