In the footsteps of the Dorians

advertisement

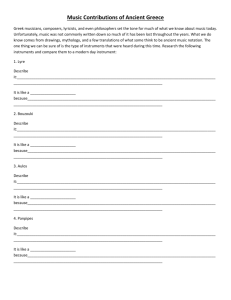

Premier’s Westfield History Scholarship In the footsteps of the Dorians Mark Adams John Paul College, Coffs Harbour Sponsored by The Dorians, an ancient ethnic group closely associated with the Spartans, other Peloponnesian states and Crete, moved down into central and southern Greece in the later part of the second millennium BC and the beginning of the first millennium BC. Their movement initiated the Greek migrations and the consequent spread of Greek civilisation throughout the Aegean Sea area and on the Asia Minor coast. In the millennia that followed, the path the Dorians traversed has been followed by the great civilisations of classical Greece and Rome and the Ottomans. In more recent times have seen this ancient area play a significant role in the history of Australia and has been pivotal in helping us to identify who we are as a nation. While the main purpose of this study tour was to develop my knowledge and understanding of the Stage 6 Ancient History syllabus, it has also made a significant contribution to my understanding and knowledge of the Stage 4 and 5 syllabi. Travel in Greece and Turkey allows us to gain a better understanding those cultures and to celebrate the similarities and differences between them. At the same time, we celebrate our common humanity and recognise what we have achieved. Istanbul was the first stop and the first significant historical building visited was the ancient and amazing Hagia Sophia. Situated in the heart of the old city of Istanbul, this church (which later became a mosque) immediately demonstrates the historical ebb and flow of this area of the world. Built by the Romans as a Christian church, it was converted into a mosque, not only reflecting the spread of Islam and the decline of the Roman Empire, but also showing how change and continuity can be represented in an historical site. Changes were made to hide its Christian heritage, and now the current Turkish Government has come to recognise its historical significance to the world. From a teaching perspective, Hagia Sophia can become the basis of a research task or a class task looking at how and why a church becomes a mosque? Or by looking at this one building we can develop in our students a better understanding of the changing relationships between nations and religions in that area of the world. There is added value in the Stage 6 syllabus as issues about ownership and preservation of the past and the factors which may influence it are questioned. Istanbul also provides an insight into the grandeur of the Ottoman Turks through the restored Topkapi Palace and its harem buildings, reinforcing the differences between the cultures of the East and the West. The National Museum of Archaeology, located in the same area of the city as the Topkapi Palace, allows us to see the size and diversity of the ancient Persian Empire. Its Roman collection shows the extent and power of the Roman Empire and how the Romans deified their Emperors. The museum’s various collections also provide materials about the way we interpret (or sometimes misinterpret) the past; for example, the ‘Sarcophagus of Alexander’, which is actually probably that of a noble of Sidon. It also shows through its collection of Cretan heads the way one place has been controlled and influenced by at least four different, significant ancient societies. Gallipoli was the next stop on the study tour and was truly a site worthy of two visits. Not only does the name ‘Gallipoli’ resonate throughout Australian history and have a significant role in the way we define our national character, but also the Dardenelles has been a strategically significant site throughout world history. To see the narrowness of the straits immediately emphasises why it would have been possible for Xerxes to build his ‘bridge of boats’ or why control of this area was so important to the ancient Greeks, Romans and Persians. Visiting the entire peninsula also reminds us that Australians and New Zealanders were not the only ones to fight and die in this place. It has consumed the bodies of British, French and Turk soldiers alike. From a historian’s point of view, this site reminds us that there are two sides to every story and that, while the Gallipoli campaign was important to our developing sense of nation, it is seen as the pivotal moment in the establishment of the modern Turkish Republic. It also demonstrates the power of language, as a dead Turkish soldier becomes a martyr to a greater cause. To walk among the graves of young Australians in such a far away place is a humbling experience. To stand in front of the grave of John Simpson-Kirkpatrick and realise that he was only in the war for three weeks is to better understand the power of image and legend. To wander along Anzac Cove and look up is to appreciate the difficulty of the task that confronted the Anzacs on 25 April 1915. Such experiences convert the teaching of Australian history from a professional task to something which resonates with passion and empathy. Troy, the next significant stop on the study tour, was fascinating. Walking among the ruins of this legendary place takes one to the beginnings of modern ancient history and archaeology. It is also here that we see how the modern Turkish Republic and archaeologists seek to protect ancient sites and to address the delicate balance between tourism and all its benefits and pitfalls with the need to maintain the historical integrity of historical sites. Indeed, this is one of the areas that the tour has emphasised, the way modern governments in all countries try to match the desire to preserve and protect areas of historical significance with the desires of increasingly educated, affluent and mobile tourists to access those areas. This critical question permeates all aspects of the Stage 6 Syllabus. From Troy the tour took me to the modern city of Bergama, home of ancient Pergamum. As you travel along the coast of Turkey towards Bergama, it becomes clear why the Greeks colonised the coast as the mountains to the east provide a formidable barrier. The acropolis of Pergamum is simply breathtaking, even if some of the reconstruction seems a little unnecessary. This site has an excellent level of preservation and really gives a strong indication of what life would have been like in this period. This is certainly one place which surprised and delighted. From Bergama to Kusadasi via Izimir was a driving experience never to be forgotten— especially as a missed turn saw this tired tourist end up on a Turkish beach. Kusadasi itself seems to be the Turkish equivalent of the Gold Coast, yet its position allows for access to some significant historical sites which vary extensively in their levels of reconstruction and ease of tourist access. Ephesus provided a perfect example of the desire of governments and archaeologists to match the demands of tourism with the need for conservation and preservation. A number of structures and buildings in this ancient city have been reconstructed, and while there I was able to observe modern workmen ‘repairing’ parts of the site. Given what has been written by those who have been involved in the reconstruction of Pompeii and the issues relating to the problems of modern cements, I was amazed to see these workmen using modern cements. After visiting Ephesus it became really clear that the levels of reconstruction at historical sites will become an increasingly significant issue for historians and the teaching of history. We must begin to ask ourselves if we are loving these popular historic sites to death. By contrast to Ephesus, the ruins of both Miletus and Priene have significantly less reconstruction and tourist activity, yet they suffer from other significant issues such as the impact of weed growth, lack of security and lack of protection. Like Ephesus and Troy before them, to visit these once thriving seaports five kilometres from the modern coastline is to better understand the impact that human activity and time can have on historical sites. The last significant action of the Persian invasion of Greece occurred at Mycale and was nominally a naval engagement close to Priene which is now land-locked. Across the ‘bay’ from Priene lies ancient Miletus with its magnificent amphitheatre and links to the Greek colonisation movements. It was the centre of the Ionian Revolt, beginning the historical period in the current Ancient History syllabus (Greek World 500–440), and was also the city whose dispute with Samos saw Athens intervene on their behalf and destroy the independence of the Samians and conveniently provide the last action of the historical period already mentioned. One aspect of the preservation of ancient sites that was raised in Miletus was the impact of changing environmental conditions. This site now has significant problems with water covering areas of the old city. It was also possible to see the difference the impact of tourism and advertising can make to the money spent on the preservation of sites. Ephesus, undoubtedly a significant ancient site, is much closer to the tourist centre of Kusadasi and seemingly more ‘popular’ than the other two sites. Consequently, the level of work in preservation and restoration is much greater. The ferry trip from Kusadai in Turkey to Samos (Greece) was very short and provided an extra day to explore Samos and reinforce the concept that maps are political entities. Hiring a car and driving around much of the island it is amazing to realise that the actual distance between Samos and Turkey is very small—much smaller than is reflected on many of the maps available to tourists. It also emphasised why Samos was such an important place in the ancient world and why its alliance or control was so important to the ancient Athenians. Mykonos was the next port of call, primarily because it provides access to the Island of Delos, legendary birthplace of Apollo and Artemis. Its historical and cultural significance is emphasised by the lack of substantial development on the island. A visit here is essential for anyone who studies or teaches the Delian League or the Athenian Empire. Delos is the central island of the Cycladic Islands and according to my guide is free from earthquakes (a ‘fact’ that the ancients knew and a reason why it was so important to them). Clearly Delos was blessed by the gods. From Mykonos I travelled to Santorini and the ancient city of Akrotiri. Again just travelling through this area by ferry emphasised how the Greeks could travel by day without passing out of the site of land, as there are islands and outcrops everywhere, some of which do not appear on standard maps. The caldera is simply breathtaking and certainly worthy of the hype and images that surround it. It leaves an indelible impression of the size of the events which sent ancient Thira into the realms of myth as possibly the lost city of Atlantis. Unfortunately the accident which closed the site of Akrotiri last year (part of a shelter over the archaeological site collapsed, killing a British tourist) meant that it was still inaccessible at the time of my visit. According to one of the assistants at the excellent museum of Akrotiri in modern Fira, the site was still closed because they are waiting for the conclusion of a coronial enquiry. The assistant also pointed out that the damage to the site was limited, with the majority of the site bring relatively undamaged. Despite this disappointment, the museums of Fira were well worth the trip, particularly the main museum which gave an excellent insight into the life of this ancient civilisation. The accident at Akrotiri does emphasise the dangers of preservation and conservation of ancient sites. In attempts to protect these places, care is constantly needed to ensure that any actions do more good than harm. While on Santorini I discovered that on a good day you could see Crete. While I was there we didn’t have any good days because I did not see Crete until I arrived there by high-speed ferry. The main focus of the tour on Crete included the Minoan civilisation, particularly the ancient cities of Knossos and Phaistos, and also visiting memorials to the Australians who fought and died on Crete in World War II. The Palace of Knossos, made famous by Arthur Evans, was something of a disappointment. Knossos was the first place I learnt about when I began my ancient history adventure in 1977, so I was quite excited about visiting this site. However, the level of reconstruction and the cement which covers some parts of the site really challenged my sense of reality. From a general tourism perspective, the reconstruction helps give a sense of the grandeur of this majestic civilisation, but from a teaching perspective we might wonder at the interpretation (and possible misinterpretations) that have occurred. It was fascinating to note that the reconstructions of Evans are now in need of repair. In contrast, Phaistos left much more to the imagination and gave a better sense of the realities of ancient sites. As with many of the sites I visited, it became apparent that each ancient civilisation layered itself on top of the previous society and I became increasingly aware of the powerful historic movements that have occurred over the centuries. A visit to the Australian Memorial at Rethymno shows that, despite the impact of World War II on the modern world, the legacy of the Nazi invasions is significantly less than the long-term impacts of the Romans, Minoans, Turks and Venetians. As with the visit to Gallipoli, it is with a sense of pride that we can observe the respect that these foreign places afford Australian soldiers’ commitments and sacrifices. While time did not allow me to visit the new war cemetery 70 kilometres up the coast, it was enough to see the impact that our ‘new’ nation has had on this most ancient island. The archaeological museum in Iraklion is a minor marvel. To wander through and observe much that has been excavated from Minoan sites on Crete is to wander through the pages of innumerable textbooks and see for yourself the items and images that teachers have been using to teach this aspect of Ancient History for the past 20 years. My frustration at Knossos was blown away by this treasure trove of Minoan civilisation. For the final part of the tour I travelled from Crete to Greece. Arriving in Athens on their Holy Thursday makes the movement out of Sydney at Easter and Christmas look like the main street of a country town on a lazy Sunday afternoon. Despite the horrors of the traffic, Meteora was worth the struggle. Visually, the monasteries did not look as impressive as the photos and television programs had made them seem, yet to learn of their history is to give them a greater significance than just being visually appealing. The Great Meteoron, the first of the monasteries to be built, became not only the centre of the Greek Orthodox religion during the Turkish occupation, but it was also the protector of aspects of the classical Greek culture while playing a significant role in the Greek independence movement of the 1820s. Delphi, Olympia, Epidarius, Mycenaea and Corinth all contributed to my rapidly developing understanding of the ancient Greeks. Any movement in this area of the Peloponnese emphasises the difficulties of the ancient societies to move freely at different times of the year. It is also interesting to be driving through mountain valleys and observe the sites of ancient battlefields such Oenophyta and Tanagra. Some of the sites and the tour as a whole were disrupted by the Greek’s adherence to the sanctity of Easter Sunday. Yet this disruption created opportunities to visit other sites that developed my understanding of the achievements and nature of the ancient Greeks. The highlight of this section of the tour was a visit to the Temple of Epicurean Apollo at Bassae, the most complete Greek temple in the Peloponnese. The importance of this historical site, located 1300 metres above sea level, is emphasised by the level of protection it has been given through the construction of a massive tent-like structure that protects it from the elements. Unlike buildings which find themselves in the middle of major cities or which are conveniently accessible for tourist buses, this site has been protected by its isolation from tourism as well as from the impact of the industrial developments of the last 100 years. The last stop on my journey was Athens, with its obvious links to the senior ancient history syllabus. Wandering through the Agora and the Keramikos develops an understanding of life in Periclean Athens and the impact on Classical Athens of the Delian League and the Athenian Empire. A visit to the Acropolis reveals the enormous difficulty involved in maintaining such a historically and commercially significant site. Scaffolding dominates and parts of the buildings are missing as they are constantly removed for repairs and restoration. The question of rebuilding the Acropolis seems superfluous as the maintenance of the site seems to consume so much time and money that it would seem improbable that the Greek government could ever do any thing more than conserve the site in its current condition. All the museums of Athens added significantly to my understanding of the history that I teach, though to stare into the mask of Agamemnon is to stare fully into the face of critical questions which surround ancient history. How and why do we preserve the past? How do we interpret the past? How do we allow access to the past? What do we learn from the past? The study tour scholarship has been a humbling experience and I feel honoured to have been given the opportunity to further develop my skills and knowledge as a history teacher and to fully appreciate the magnificence of the civilisations that have trodden the path first established by the footsteps of the Dorians.