On translating metalanguage: the language of linguistics

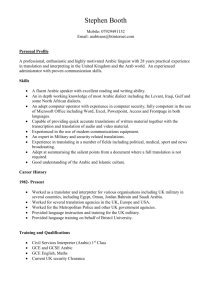

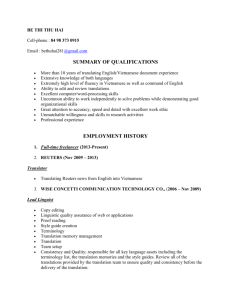

advertisement

لغة التخصص :مقدمة في ترجمة المصطلح اللُّغوي الدكتور دنحا طوبيا كوركيس أستاذ علم اللغة – قسم اللغة اإلنكليزية – كلية اآلداب – جامعة الموصل ملخص من البديهي أن تكون لغة أهل العلم ،وبخاصة علم اللغة ،لغة تتخصص بمفردات يصعب على المتىرجم أحيانا اإلتيان بمثلها في لغته ،إذ تكمن هذه الصعوبة في فهم مدلوالت المصطلح األجنبي من جهىة وفىي إمكانية التعامل مع الموروث اللغوي العربي من جهة أخرى .لذلك نراه يلجأ تارة إل التعريب وأخىرى إل تفسير المصطلح أو كليهما معا ً رغم أن للعربية قدرة عالية على احتىوام ملىكلة المصىطلح الغربىي بمىىا يتناسىىب وصىىناعة المعجىىم اللغىىوي العربىىي .وبهىىذا ىىاعي الفرديىىة فىىي غيىىاب المصىىطلح القياسىىي وظهرت ملكلة التباين وعدم توخي الدقة في الترجمىة مىن اإلنجليزيىة مىثلً إلى العربيىة .وكىان فىي عون القارئ العربي طالما كاني الجهود مبعثرة والمنهجية في سبات عميق. وبسىىبب كىىل مىىا تقىىدم ارتىىأى الباحى أن يطىىور مىىن حيى المبىىدأ منهجىا ً بخمسىىة معىىايير يقىىيم الحجىىة مىىن خللها عل صلحية ال ُمترجم وال ُمعرب من المصطلحات اإلنجليزيىة مىن عىدمها .ويطىر فىي ىو ها البىىدا ل التىىي تتنىىاغم مىىع موسىىيق العربيىىة فىىي منةوماتهىىا الصىىوتية والصىىرفية وسىىياقاتها النحويىىة إل ى أقص حد ممكن ،األمر الذي حدا بالباح أن يطلق عل هذا المنهج تسمية جديرة بمنطلقاته ،هي : نةرية االحتوام واإليوام هذه النةرية التي ندعو إل تطويرها بجهود عربية ملتركة ،والتي من أنها أن تلغىي دور االنطباعيىة في تقييم وو ع التراجم سعيا ً إل و ع معجم قياسي للمصطلحات اللغوية. 1 On translating metalanguage: the language of linguistics Prof. Dr. Dinha T. Gorgis Dept. of English, Collage of Arts, University of Mosul, Iraq ABSTRACT If language is easy to translate, the language about language, i.e. metalanguage, is NOT. Unless some conceptual apparatus or framework is designed to provide a set of criteria against which translatability can be questioned and, hence, tested and evaluated, individual translation efforts, though valuable, are expected to remain on the scene without enabling prospective translators to overcome the difficulties underlying those efforts in the first place. The principal difficulty encountered in approaching the language of linguistics, as of any special register used in other sciences, is the set of technical vocabulary which does not necessarily express the same value across languages. Even when it does, there is the problem of 'inability' to cope with already existing technical terms in the target language, e.g. Arabic, in which case the translator (or the lexicographer) appeals to literal translation, arabicization and/or paraphrases. In the absence of a standard Arabic register, the translator is partly held responsible for the reader's incomprehensibility. To circumvent these problems, the present paper addresses the question of how translatability of (English) metalanguage can be made feasible within a five-point programme that is intended to develop an accommodation theory of translation. This model stipulates that available translations of English terms into Arabic can be accepted, rejected and/or replaced. While current translations are basically meaning-based, the theory is additionally both system and principle-based. That is, in selecting a translation equivalent for a given English term, all aspects of Arabic grammar plus some pragmatic factors can help make appropriate decisions between this and that translation of the same term. This theory has the advantage of bidding farewell to impressionistic judgments that swing between 'good' and 'bad' quality of translation. 2 On translating metalanguage: the language of linguistics Prof. Dr. Dinha T. Gorgis Dept. of English, Collage of Arts, University of Mosul, Iraq INTRODUCTION We all perhaps agree that the translation of metalanguage is as twice difficult as translating natural language, and the ability to carry out the former task usually presupposes the latter, but not vice versa. For it would be sufficient for a good translator of, let’s say, an English novel into Arabic to be proficient in the two linguistic codes and, as a given, knowledgeable in the two respective cultural patternings as well as a skilful engineer of literary style. S/he need to know, as prerequisites, about the author's other writings and/or his/her critics' views or even comparable works of his/her contemporaries, if any, though the provision of such background would be useful. Whereas the translator of, e.g. linguistic texts from English into Arabic need to have a considerable amount of knowledge about the history of linguistics, adequate training in current and competing linguistic theories and, above all, the conscious workings of Arabic grammar. It is the latter requirement that ought to distinguish this (super) translator from conventional translators who faithfully pass over meanings to the Arabic reader. Based on this understanding, I have, for over two decades or so, been hesitant to translate a textbook or even an article written in English into Arabic and vice versa, indeed, despite my very good command at both languages. When Baghdad University formally recognized modern linguistics as a worthwhile academic discipline in 19731 (at the M.A. level), I was encouraged to translate D. Crystal's What is linguistics. Though the language and style of the book are fairly easy, I stopped in the middle for fear that the reader would not be able to understand me. Since then I have been acquiring more 3 linguistic knowledge through intensive research and running linguistic courses at the B.A, M.A., and Ph.D. levels. Thus, having gained more confidence and had better training than before, I decided to translate G. Leech's Principles of Pragmatics in 1992. It all went smoothly at the beginning but, again, I stopped half way through. My colleague, Prof. Y.Y. Aziz (a renowned translator, now at Ben Ghazi University) who read and appreciated my translation, was entrusted to complete the translation of this valuable textbook. But due to technical difficulties of publication in Libya, as he wrote to me, my own 'half' was returned after having made several requests. Now it awaits completion! Even when completed, the fear that has always irritated me, viz., that the reader would not be able to easily follow the translation of metalanguage, is justifiable. For, at least, the old question: For whom do we translate? cannot be answered adequately. Do we translate for an Arab grammarian (and his/her students) or, to put it bluntly, for university students majoring in linguistics and/or translation to be enabled to understand better a given linguistic text written in, let's say English? When asked to read and interpret part of a translated text, e.g. Y. Y. Aziz's version (1987) of Chomsky's (1957) : Syntactic Structures, the former group (comprising a number of teachers and their students at the Arabic Dept., Univ. of Mosul.) found Aziz's translation incomprehensible. When the same translation was presented to the second group (comprising a number of graduate students at the departments of English and Translation), it was found more difficult to follow than the English text. And between these two groups stands the poor average reader who may have some knowledge about linguistics. No wonder we, too, find it sometimes difficult to follow (parts of) a translated text without recourse to the source version. Whichever group of readers we have in mind, the problem of incomprehensibility remains as long as there is lack of a standard metalanguage, i.e, agreed upon Arabic linguistic register, which ought to be founded on well-motivated criteria. One may also 4 argue that the difficulty is not one of finding a standard Arabic equivalent to an English term only, but of mismatching and/or misconception of the part of the translator. A good example supporting this claim is Chomsky's AUX, translated by Al-Sayyid (1989), among many others, as ( الفعل المساعدsee below for discussion). The above two factors (among others which we exclude from the present study), viz., the absence of a standard register and a noticeable 'deficit' in proper linguistic orientation, have naturally led to the existence of unwanted variations (in contradistinction to the variations that we find in literary translation, which are basically aesthetic). Evidently, 'heterogeneity' is also the outcome of different, though proper, linguistic orientation characterizing Arab scholars (linguists and/or translators) across Arab countries. Thus, it is expected to find a translation done in Morocco to be different from the translation of the same text done in Iraq, Syria, or Jordan, even if the two translators are of equal academic status and training. In fact, the difference would mainly be due to differing linguistic traditions, say French vs. English or continental vs. Anglo-American, etc. with varying degrees of bringing Arabic grammatical tradition to the fore. Against this brief account of the present state of affairs, I should conclude this introduction by saying that the small number of linguistic translations made available to us are mostly the product of individual efforts, generally meaning-based and, above all, characteristic of literal translation, arabicization, and paraphrases, not to mention inaccuracies and infelicities of style. DISCUSSION In what fellows, I shall demonstrate with several comparable examples taken from a number of texts and dictionaries that our current and diverse efforts to approach the foreign linguistic register and, hence, render it into Arabic need to be reconsidered in the 5 light of what I presently may call 'accommodation'2 theory of translation, some details of which will be outlined below. At this point, it must be admitted that the criteria put forward are suggestive rather conclusive. And in the light of these criteria, which I take to form the basic tenets of the theory, I intend to evaluate and test a handful of linguistic terms as conceived and, hence, rendered into Arabic by a number of Arab scholars, notably Aziz (1985; 1987), Al-Hamash (1982), Bakir (1985), and Ghazala (1996), among others (see references). Primarily, I should like to avoid an authoritarian air by taking Al-Karmi's (1995) reported 'prerequisites' for both a technical and literary translator as a given, though some of them may be challenged. My focus, however, is on the linguist, students of linguistics and/or translation, whether trained or under training. Some of the following criteria (hopefully not all!) seem to be quite common, but as they are thought to fit in well with the whole proposal their mention and, hence, discussion, ought to be implemented in an integrated theory of translation. This theory, however, stipulates that any given term intended for translation into Arabic must comply with at least one of the requirements obtainable from answers to the following set of questions: 1. Does the English term have a one-to-one correspondence with an already existing term in Arabic grammatical tradition? If answered in the affirmative, there is no point in translating, e.g. category into قاطغوريىاor صىنas do Aziz and Bakir, respectively, among others Rather, the widely used Arabic grammatical term that ought to have been selected is ( بىابcf. Shanni 1977). If answered in the negative do as required below. 2. Is the term translatable into Arabic as word for word without paraphrasing or compounding such that the new term, which has no equivalent value in Arabic grammatical practice, can be an easy bed-fellow with already existing terms in Arabic? If yes, then why not translating, e.g. Chomsky's AUX (as made explicit in the Standard Theory) into السىاندto form a tripartite with the current المسىندand المسىند 6 ?إليىهThat Al-Sayyid (1989) conceives of it as الفعىل المسىاعدis untenable; for the Phrase Structure Rule that rewrites AUX, according to the above-mentioned model, as TENSE obligatorily also rewrites the Modal and aspectual auxiliaries as optional elements which all belong to the traditional category 'auxiliary verb' and, hence, the misconception (see Gorgis 1989a). This misconception, however, seems to have a long-standing tradition of the Translation Method in teaching foreign languages, which equates 'auxiliary verb' with 'helping verb' and, hence, the present literal translation against which our alternative, الفعىل السىاند, would be in conformity with the set members suggested above, though both translations may be said to be semantically based (but see below). Now if a further 'yes' is given here, another question inevitably emerges, viz. Does the Arabic term thus selected find proper accommodation within the overall phonological and morphological patterning of standard Arabic? If yes, check it against both number and gender systems. And when you feel you have succeeded in finding a candidate term, test (3) below could be conclusive unless there are (better) competitive translations. For the moment, take the term 'concept', also common in other genres, which Aziz (1985: 85ff) has translated into فكرةin accordance with the present requirements (but see below). 3. If all goes well with the previous procedures, you need now to be more on a solid ground by making preferences between the term already chosen and another competitive term on the basis of syntagmatic relations, whether at the morphological and/or syntactic level. That is, we should be enabled to see for ourselves which of the two terms finds a better shelter at these levels, provided that neither of its derivatives is already a translation of another word in the English lexicon. For example, فكرةis as good as مفهىوم, so to speak semantically. But once each term is made dual, plural and, above all, related to the English adjectival and adverbial forms, viz. 'conceptual' and 'conceptually', we expect, to follow Aziz, to have the following derivatives: فكرتىان, أفكار, فكري, and ً فكريا. But if we opt for our alternatives, though not without difficulties, we obtain in that order: مفهوم, مفاهيم, مفهومي, (cf. تصويري, in Ghazala 1996), and ً مفهوميا. 7 Now suppose we ask a question such as: what is a word? One of the expected answers would be: it is a concept, for which Aziz's فكرةcannot stand. And since other words, e.g. idea, thought, intellectual, and the linguistic term 'ideational' (cf. Ghazala 1996), are commonly rendered into فكىرةand its derivatives, my options would be more convenient. But despite this preference, the difficulty facing the translator is mainly one of contextualizing the term and its derivatives, if any. Suppose we wanted to translate the noun phrase: 'the students of conceptual semantics' in three ways. According to Aziz, we may roughly get: علىم الداللىة الفكىري..., while according to Ghazala, we get: علىم الداللىة التصىويري.... For our own part, we get: علىم الداللىة المفهىومي.... My intuition dictates that none of the three translations would make much sense. So we better shift ranks. That is, the English adjectival form would be realized as a plural form in this context. Thus, a first preference would be given to علم داللة المفاهيم, a second preference may be given to علم داللة األفكار, but nil preference to علىم داللىة الصىور unless الذهنيىةmodifies الصىور. And on a similar basis, we tend to reject the translation of 'conceptualization' as تفكيىر, تصىوير, or my erroneous تفهىيم. Rather, we choose to render it into )عمليىة( تكوين المفاهيمor the like. One might argue here by saying that rank shifting is technically a costly procedure. Positively; especially, when long paraphrases are involved. It must be remembered, however, that we are primarily interested in establishing sets of technical terms relevant to linguistic register. This measure, therefore, is meant to be taken in cases whereby there is no one-to-one correspondence at the same rank and/or category level. 4. Related to (1) above, but slightly different, is the question of medieval vs. modern terms. Unlike the modern Arab grammarian who is aware of the former and fascinated by the latter, the translator is required to correlate between the two. Unless this is done, the old terms remain forgotten and the innovated ones replace them. But this is unfair, unless there is good reason for so doing. For example, I find no convincing reason why the currently used السىياrather than المقىامbe the translation of 'context'. Don't you think that the famous statement لكىىل مقىىام مقىىا, introduced by 8 Medieval Arab grammarians, stand fairly well for Malinowski and Firth's 'context of situation'? Unlike the status of 'category' discussed in (1), it would probably be too late to suggest a replacement. Instead, we either endorse both or choose between them, whereby the one that is least connotative, more pertinent to the genre in which it is being used, and has been established as a convention, will be selected. Thus, the one that is much in vogue, I reckon, is: السىيا. But a dictionary-maker should not lose sight of the other. Similarly, the two notions introduced by Chomsky (1957; 1965), viz. 'deep' (underlying) structure vs. 'surface' structure, and translated variously into: 1. البنيىة العميقىة vs. البنية الةاهرة2. التركيب الباطنيvs. التركيب الةاهري3. البنيىة التحتيىةvs. البنيىة الفوقيىة4. البنىام العميىق vs. ( البنىىام الةىىاهرcf. Al-Hamdani 1982: 129, among many others), also have their correlates in medieval Arabic grammar. For example, Al-Zajjaji (d. 949) is reported by Peterson (1972) to have drawn a distinction between معنىand ( لفىtaken from Arabic rhetoric), where neither the former refers to the meaning of a word, nor the latter refers to the phonetic form of the word. Rather, the former term accounts for the underlying (presumably semantic) structure of a sentence while the latter for its phonetic representation. Certainly, the two paradigms, viz. Chomsky's and Al-Zajjaji's, are different, but when notions across different traditions denote similar values they may be equated, at least roughly. This juxtaposition has a parallel in the linguistic literature. Recall here, for example, the rough correspondence made between Saussure's 'langue' vs. 'parole' and Chomsky's 'competence' vs. 'performance'. After all, terms are arbitrary concepts upon which we first impose signification and, then, when widely recognized by concerned circles, they become conventional. But when no longer in use, they are simply shelved and, hence, forgotten. And this, generally speaking, is our present state of affairs in the Arab world. The question that remains to be answered, however, is: Do we need to revive the medieval notion and simultaneously encourage (or perhaps stop) innovations? I have 9 implicitly answered the question, though partly, in connection with the translations of 'context' above. A counter-argument would be one that discourages rebirth on grounds that: (a) the traditional terms have become obsolete; they no longer express the same value as their assumed correlates in current use; (b) many are so common that their meaning today departs largely from the traditional uses for which they were intended; (c) a considerable number of these terms have their origin in rhetoric; (d) modern Arab grammarians are no less talented than traditional grammarians in developing metalanguage that can keep pace with progress. Obviously, one can argue for and/or against such views. But as their discussion would take us far beyond the scope of the paper, I leave the issue open for further research. Instead, we proceed with our programme. 5. In case the previously discussed criteria do not satisfy all of your translation needs, the following may be utilized: (a) Coin a term by means of a suitable morphological process when literal translation is not possible; (b)Arabicize when deemed necessary; and (c) Paraphrase, but not at the expense of either (a) or (b) unless objectives are different. These procedures are naturally costly. In order to keep the cost at a minimum, the order in which they appear here must be maintained. For if you opt for paraphrasing, for example, you lose sight of building up a stock of corresponding concepts which arabicization or coining can handle more easily. In short, do not attempt to adopt a lower procedure at the expense of a higher one. Nor, indeed, all of them ate the expense of the previously established ones, in which case you better stay as close as possible to Arabic phonological, morphological, and syntactic patterns. 10 Technically, this task, as before, expresses one sense of ‘accommodation’, i.e. let things fit in pretty well with the overall Arabic grammatical system. And as I take the foregoing set of criteria and assumptions to constitute a conceptual apparatus within which I shall discuss several renderings, I also take the liberty to use ‘accommodation’ in a second sense, viz. that which expresses a relationship between the rendered terms and the model that accounts for them. In plain words, this would mean: let the suggested equivalents abide by the underlying principles. So much for the theory. Let’s now move to discussion. First, we consider the problem of coining, but not without reference to the other criteria. Relevant to coining is the notion of ‘blending’, a sort of compounding whereby the constituent parts of the newly created word(s) are intended to express a similar sense to that conveyed by the English term. As an example, I take the term ‘morphophonemics’ itself a blend, which is often used interchangeably with ‘morphophonology’ or just ‘morphonology’. Disregarding differences between them, the term was originally introduced by Bloomfield prior to the publication of his Language. Considered as a branch of Structural Linguistics in the post-Bloomfieldian era, the term expresses an intimate relationship between phonology and morphology (cf. phonemics and morphemics) whose basic units are respectively the ‘phoneme’ and ‘morpheme’. Except for ‘morphophonemics’, all other related terms have been translated and/or arabicized in the following manner: (علم) النةام الصوتي؛ (أصىغر) وحىدة صىوتية, or المىورفيم؛ (أصىغر) وحىدة صىوتية, or الفىونيمor فىونيمكسand (علىم) الصىرor مىورفيمكس. Based on these renderings, among others, we expect our term to be rendered into: فونومورفيمكسor ( مورفونيمكسas arabicized blends). But since we want to solve the problem as required by 5.a above, we appeal to literal translation; thus, the uneconomical and inaccurate النةىام الصىوتي والصىرفي. Instead, we suggest either الصصىرفيات, on the basis of analogy with many technical words used in other genres, or (دراسىة) السىلوا الصىوتيas a translation equivalent which is partly based on the practice of traditional Arab grammarians and partly on the understanding of the field 11 itself. Still, we prefer our blend for at least two reasons: On one hand, our goal is, to reiterate, more of concept than phrase oriented. On the other hand, when the blend functions as an adverb or as a modifier to a head, e.g. rule, it lends itself more easily to case endings as required, for example, by agreement. Thus: (قواعىىد) صص ىرفيةfor 'morphophonemic rule(s)' and ً صصرفياfor 'morphophonemically'. Arabicization, as we have just noticed, is not to be recommended when there is a way out. To my thinking, many arabicized terms come into existence because: a) their producers have a limited knowledge about the field, whether in the source language or target language (though competent in both languages); b) the field of enquiry could be still young so that its underlying assumptions and notions are not clear enough to be equated with what is available in Arabic; or c) there is a feeling that Arabic is in need of a universally acknowledged set of technical terms; or even the least likely d) it is the easiest process. Not too many will make fuss about them; for they are often justifiable and can easily be replaced when difficulties unfold. To make this picture clearer, let me introduce the term 'pragmatics'. Some fifteen years age, I introduced this field of enquiry to the readers of Al-Hadba weekly, published in Mosul, under the title which reads: مىا هىي البراغماتيكىا. Upon reading this brief article, my colleague, Yowel Y. Aziz, commented: "why not "?براغماطيقىىاI readily accepted his modification because it reminded me of similar analogues, e.g. هرطقىةfor 'hypocrisy'. The earlier form did not live long because it was soon replaced by the second (cf. Gorgis 1989b). Following my proposal, Mosul University has been running a pragmatics course for Ph.D. students majoring in English language and linguistics. M.A. students doing translation are having now a course under the label: semantics and pragmatics, and M.A. students majoring in English literature will have the pragmatics of literature next term. It is to be noted that none of the other Iraqi universities is running 12 pragmatics courses. A similar sad situation seems to prevail in other Arab countries; for only a few number of researchers are affiliated to IPrA and only a small number of papers have addressed issues within pragmatic perspective for the last fifteen years or so. Still worse is the absence of translated literature despite the fact that numerous introductions to the field have appeared since the publication of Jacob Mey's Pragmalinguistics in 1979. The only relevant work made available to us is Ghazala (1996) in which we find a number of translated notions that also need to be reconsidered in the light of our present programme. For the time being, however, we take his translation of 'pragmatics' which reads: علىم الىذرا ع. Regrettably, this translation, like الىذرا عياتadvocated by Al-lisan Al-'arabi, is much closer to 'pragmatism' فلسىفة الىذرا عthan to the tenets of 'pragmatics'. Incidentally, I came across البرغمتيىةin Ibn Khaldūn after I had suggested the now-in-use براغماطيقىا. Although the former relates to philosophy and the latter to communication, I was disappointed; for both are arabicized forms that could mean the same for the reader. So I went as back as 113 B.C. to trace the origins of 'pragmatics' (in contradistinction to the American philosophy 'pragmatism'). I came to the conclusion that 'action' and 'utility' are two key terms in present-day rpc scitam arp which I suggested the Arabic equivalent الفا داتيىةto my students. When this translation was circulated, one of my students (now teaching in Libya) brought to my attention a second best term, viz. النفعيىة, being the translation of 'utilitarianism'. Although my coin violates the rules of word formation in Arabic, it sounds Arabic. One may reasonably argue here that I am betraying the criteria already discussed. I agree, but let me defend my position. Intuitively, I feel that نفعيىةis as good and, yet, as connotative as ذرا عيىةroughly corresponding to Leech's (1983) 'means-end analysis'. Moreover, these two, supposedly, equivalent terms are philosophically oriented. Therefore, I am more for defining the relatively new field of pragmatics by our innovated word than any of the ones mentioned above. But one may also suggest, that 13 براغماطيقىاbe used, at least parenthetically, as long as it has been recognized officially. Thus: ) الفا داتية (البراغماطيقاwould be two faces of the same coin. Parenthetical coupling (in the sense just used) is only meant to be a temporary measure. Another type of coupling which is extensively used in the literature is that whereby the alternant, usually taking the form of a paraphrase (and, sometimes, a definition), follows an arabicized form. If the former procedure is adopted systematically as a strategy, it will have the advantage of creating synonymy. But when the latter is encouraged, it will have the advantage of explanatory methods pertinent to pedagogy, but the disadvantage of losing sight of the ultimate goal, viz. building up a stock of technical vocabulary for which a prospective dictionary-maker aspires. Paraphrases, however, also appear frequently in the translated literature without arabicization. My position is that paraphrases, whether being coupled by their respective arabicized equivalents or not, should not be done at the expense of any of the foregoing criteria unless they are well motivated. As examples for unwanted coupling, take the term 'phoneme', arabicized by Aziz (1985), among others, as الفىونيمand defined (see p. 266) as أصىغر وحىدة صىوتية للتفريىق بىين المعىانيor 'aphasia', arabicized as أفلىياand defined as ( فقىدان القىدرة على الكىلم والفهىمp. 257). While it is possible to suggest Arabic equivalents which can convincingly stand for these two terms, e.g. صىوت مجىرor عا لىة صىوتيةor just وحىدة صىوتيةfor the former, and الحبسىة for the latter, coupling of this sort must be discouraged as long as there is much room to accommodate such terms fairly well within our proposed criteria. By the same token, the other type of paraphrasing, i.e. without coupling, will also find difficulties within our model. Take, for instance, Ghazala's (1996) alternative translations to each of the three basic notions advanced by Speech Act Theory, viz. 'locutionary act', 'illocutionary act', and 'perlocutionary act'. The number of interpretations given to each is in that order as follows: five, four, and five, the majority of which do NOT comply with the underlying principles of our accommodation theory. For one thing, at least, most of his translations 14 (inaccurate, though) cannot be made plural or modified, say by 'two' or 'several', in which case generalizations are not possible. Consider the first (out of five) translation given to the first type of act which reads: ً أدام القىو لفةىاand the fourth (again out of five) translation provided for the third type of act which reads: مفعو أدام فعل ما ونتاجه. I do not intend to take this exposition as a criticism (which he seems to frown at). Rather, we want to test the validity of our programme against a number of available translations; his do not fit well. Therefore, I may suggest a trichotomy which coheres with our framework. Thus, while maintaining the reported order, the suggested equivalents can be فعىل النطىق: فعىل المنطىو: فعىل اإلسىتنطاor more down-to-earth tripartite فعىل الىتلف: فعىل الملفىوظ: فعىل الملفةىةin which case the translator would not encounter any difficulty as regards contextualization and, hence, the successful application of our proposed accommodation theory3. CONCLUSION At the outset of this paper, it was suggested that in order to translate metalanguage, in contradistinction to literary language, the translator ought to be adequately trained in different linguistic theories and, above all, be aware of the working threads of Arabic grammar to a considerable extent. Still, it was noted, there is always the fear that the reader would find a translated linguistic text incomprehensible. The source of difficulty was ascribed mainly to the absence of standard terminology in the Arab world4 and mismatching owing to misconception. Both of these, among other things, have motivated us to claim that many linguistic terms that have been translated into Arabic and/or arabicized need to be considered in the light of what we have come to call 'a translation theory of accommodation', one which presently advocates a five-point programme (subject to criticism and/or revision) that is equally thought to enable the prospective translator of linguistic register to see into the nature of intricacies involved. As we have seen, a small number of translated examples have been tested and evaluated, 15 though roughly, against our criteria which yielded better results. We, thus, come to the conclusion that if one term lends itself more easily to the underlying principles of the proposed model, i.e. if it accommodates better within both Arabic grammar and the framework, than an already existing term, our choice must rest with the first without reservation. 16 NOTES 1. Before that, specifically starting the academic year 1968-69, my teacher, Mahmood Al-Marjani, a Brown Univ. graduate (now lecturing at Ben Ghazi Univ.) introduced me to phonology as a requirement of an English pronunciation (phonetics) course. To him, I owe a great deal for that excellent introduction. 2. Borrowed from phonological theory with courtesy, the term may be used interchangeably with 'adaptation', to follow Verschueren (1987). Though the two constructs are differently motivated, they would mean here something like: let things fit in well. 3. For better or worse, this theory can be taken as a working hypothesis. The least that can be said in its defense at present is that it seeks 'harmony' between related concepts at whatever level. But, certainly, more detailed accounts are required to verify its credibility (see also n.4 below). 4. One may, to the contrary, argue that a fair amount to work has already been published by Al-Lisān Al-'arabi which could be claimed to represent a standard. In this vein, Al-Fahri (1983; 1986a; 1986b; 1987 and Al-Hamzawi (1980), among others, must be acknowledged. But like all others, e.g. Bakalla et al. (1983), AlKhuli (1982), and Aziz (1985; 1987), to mention but some, they all need to be tested against our theory or, perhaps, a comparable one. Furthermore, there is the suggestion that calls for joint efforts, i.e. a more balanced coordination between Arab scholars with western orientation and Arab grammarians lacking that orientation. This move, intended to remedy the present situation, has the double advantage of bringing together prominent representative practitioners from both Asian and African Arab countries to, first, exchange views and remove differences and, second, establish a coherent program, in the light of which a unified English-Arabic linguistic dictionary can be compiled. 17 REFERENCES Al-Fahri, A.A. (1984). "The linguistic term" (in Arabic). Al-Lisān Al-'arabi, 32: 139147. Al-Fahri, A.A. (1986a). "The linguistic term" (in Arabic). Al-Lisān Al-'arabi, 26: 193240. Al-Fahri, A.A. (1986b). "The linguistic term" (in Arabic). Al-Lisān Al-'arabi, 27: 259274. Al-Fahri, A.A. (1987). "The linguistic term" (in Arabic). Al-Lisān Al-'arabi, 28: 217234. Al-Hamash, K.I. (1982). A dictionary of linguistic and phonetic terms: English-Arabic. Baghdad: Al-Rasheed Press. Al-Hamdani, M. (1982). Psycholinguistics (in Arabic). Mosul: Mosul University Press. Al-Hamzawi, M.R. (1980). "Modern linguistic terms in Arabic studies" (in Arabic). AlLisān Al-'arabi, 18/2: 87-122. Al-Karmi, H.S. (1995). "Translation – A problem". Al-Lisān Al-'arabi, 40: 43-46. Al-Khuli, M.A. (1982). A dictionary of theoretical linguistics: English-Arabic, ArabicEnglish. Beirut: Lebanon Library. Al-Sayyid, Sabri I. (1989). Chomsky: paradigm and critics (in Arabic). Alexandria: Dār Al-Ma'rifa Al-Jāmi'iyya. Bakalla, M.H. (1983). A dictionary of modern linguistic terms: English-Arabic, ArabicEnglish. Beirut: Lebanon Library. 18 Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic Structures. The Hague: Mouton. Arabic Version, by Y.Y. Aziz (1987. Baghdad: Dār Al-Ma'moun. Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Mass: MIT Press. Arabic Version, by M.J. Bakir (1985). Mosul: Mosul University Press. Ghazala, H. (1996). A dictionary of stylistics and rhetoric: English-Arabic. Malta: ELGA Publications. Gorgis, D.T. (1989a). A review article of Al-Sayyid (1989). Baghdad: Al-Jāmi'a Weekly, 20: 2. Gorgis, D.T. (1989b). "On terms in modern linguistic studies" (in Arabic). Baghdad: Al-Jāmi'a Weekly, 26: 7. Leech, G. (1983). Principles of pragmatics. London: Longman. Peterson, David (1972). "Some explanatory methods of the Arab grammarians". Papers from the 8th Regional Meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society, 504-515. Saussure, F. de. (1974). Course in general linguistics. Fontana: Collins. English Translation by Wadi Baskin (1959). New York: Philosophical Library. Arabic Version by Y.Y. Aziz (1985). Baghdad: Afāq Arabiyya. Shanni, A. (1977). "A glossary of linguistic sciences" (in Arabic). Al-Lisān Al-'arabi, 15/2: 115-138. Verschueren, Jef. (1987). Pragmatics as a theory of linguistic adaptation. IPrA Working Document I. 19 This paper, which has generously been retyped by Saeed Hizam for WATA exclusively, appeared in Translation Studies, The Quarterly Journal of the Department of Translation Studies, 1999. Vol. (1): No. (2), PP. 9-22. Baghdad: Bayt El-Hikma. In case researchers need to quote from the journal, they are advised to drop me a line so that I provide them with the relevant page(s) in which the requested material is to be quoted in their work. For enquiries, please do not hesitate to contact me at: gorgis_3@yahoo.co.uk 20