Stability, trended change or data artefacts: pooling forty years of

advertisement

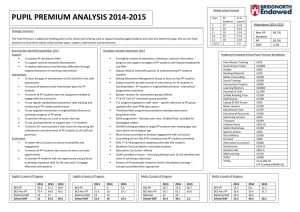

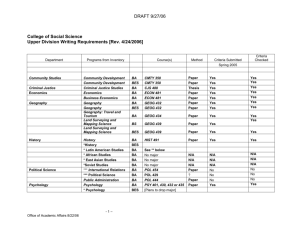

Stability, trended change or data artefacts: pooling forty years of social mobility enquiries in the UK Paper prepared for the ISA RC-28 Social Stratification and Mobility conference, New York 22-24th August 2003-08-20 Ken Prandy Cardiff University, UK Paul S. Lambert Stirling University, UK Marge Unt Tallin P University, Estonia Paper download: www.staff.stir.ac.uk/paul.lambert/downloads.html Associated project: www.cf.ac.uk/CAMSIS/socmob 1 Social mobility in the UK: “Stability of relative inequality” paradigm Popularly adopted and maintained Based primarily on cohort comparisons Methods likely to reject small changes Recent challenges Longer term data can detect change Payne and Roberts: BES studies changes Family history project: trend of decline throughout 19th Century Prandy et al 2002: decline in 20th Century data Current project: ‘long run changes in significance of social stratification’, collated X-section data with occupations, background, voting, lifestyle, … Here attempt: Further evaluation of mobility trends Role of education Robustness of trends to alternative modelling 2 ‘Long Run’ dataset: Harmonises ~20 cross-sectional surveys Different sampling, coding frames, contexts Possible use of panel data recontacts Possible work life history records Key variables: 1. Respondents Own Occupation 2. Father’s occupation (at age 14) 3. Education (3, 4 category summary) 4. Time of record or Year of birth 5. Age of respondent 3 Occupational mobility : controversies over occupational indicators 1) Continuous measures Reference to position in a structure of differences Concentrating on one dimension of hierarchy Suited to simpler modelling techniques and interpretations CAMSIS measures: typical occupational stratification location as estimated through social interaction patterns exhibited by occupational unit holders Relative position within time period and gender 2 UK versions used, 1971 and 1991, by gender 2) Categorical schemes More prominent in mobility research Emphasise bounded structures Fixed in time and by gender Encourage qualitative assessments of positions Less suited to simpler summarising models 4 Father-child CAMSIS correlations: high to low, by birth cohort, study, and study period: Men 1890 1910 1920 1930 1940 1900 1950 1960 1970 1980 74 CAM 73 Irel 92 BES 79 BES 72 Nuf 74 Scot 63 BES 74a BES 74b BES 97 BES 83 BES 96 Nirl 87 BES 91 BHPS 84 Class 86 SCELI Women 1910 1920 1900 1930 1950 1940 1960 1890 1970 1980 1976 1971 1965 1981 1991 1996 2000 1986 97 BES 74a BES 74b BES 92 BES 84 Class 87 BES 83 BES 96 Nirl 63 BES 79 BES 86 SCELI 91 BHPS Some suggestions of trends, esp for men But much noise also 5 1976 1981 1986 1996 1991 1965 2000 Regression models to assess multiple influences predicting occupational outcomes Interactions between year / period and fathers occupations of most interest Men Women 4a.2 4a.4 4a.6 4a.8 FCS AGE AGE2 YEAR YEAR2 +++ +++ --+++ --- ++ ++ -+++ --- +++ +++ ----- + + --- ED1 ED3 EDV FCSAGE FCSAGE2 FCSYR AGEYR FCSED1 FCSED3 AGEED1 AGEED3 YRED1 YRED3 --+++ --+++ --+++ +++ ++ --+++ +++ ----+++ --- --+++ +++ ++ R2*100 --+++ 35 35 6 -+++ 32 + + +++ +++ + --+++ + 31 Determinants of education: Men FCS AGE YEAR FCSAGE FCSYEAR AGEYEAR 5a.2 +++ --+++ +++ +++ +++ 5a.3 +++ --+ +++ ++ C/S R2*100 19 11 Women 5a.6 5a.7 +++ +++ ----+++ +++ +++ +++ ------26 22 Suggesting net patterns of: Men: Direct occupational immobility But educational immobility Albeit with declining impact on occ outcomes Women: Direct occupational immobility [unclear] But educational immobility 7 Potential errors (1): appropriate occupational measure? Predictions of CAMSIS with father’s job categorised variously: Artificial CAMSIS break (1980) has some significance Most category estimates seem aligned with a hierarchy anyway Some significance to CASMIN agricultural categories Predictions of current job in EGP or RGSC categories: Broadly similar structures to dummy category main and interaction effects, though much more detail to the interpretation of each coefficient Interactions with time much more complex: don’t get the simple conclusion of increased or stable mobility eg male RGSC ordered : +ve (adv): ED3, FRG2ED1, FRG4ED1, FRG3ED1, AGE, FRG3YR, AGEYR, AGEED3 -ve (disadv): FRG5, FRG4, ED1, FRG3, FRG2, YEAR, YRED3, FRG5AGE, FRG3AGE, FRG4AGE, AGEED1 8 Potential errors (2): structural influences on mobility propensities? For CAMSIS outcomes, time period effect theorised as sufficient control for structural change, given relative average locations Tests of influence of ‘sector’ dummies and ‘inheritance’ effects show no significant impact upon other variable parameter estimates Potential errors (3): survey sampling effects? Large main effects – surveys influence outcome distributions But negligible influence on other variables’ prediction coefficients Stable patterns within restricted age groups : not just an age-period conflation Between country differences: NI and Scot have larger main effect immobility but greater rate of decline over time 9 Conclusions Estimates of father’s-occupation influence on educational attainment and occupational outcomes seem robust to methods variants, covering: Survey effects Occupational measurement type Structural mobility accounts Interaction terms show gender differentiation whereby: Men have net declining direct occupational relations, but increasing father’s influence on educational levels Women have no discernible net occupational trend, but declining influence of fathers on educational levels Use of path model formulations, SEMs, may account for magnitudes involved better 10