AWEL TRAINING GUIDE

advertisement

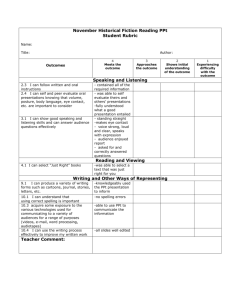

AWEL TRAINING GUIDE LEADERSHIP ONE Action-Centred Leadership Transactional/Transformational Leadership & RAF Leadership Attributes INTRODUCTION The principle aim of this training guide is to assist you in achieving the lesson’s training objectives. As such, it is provided to make your life easier and not to constrain your imagination or ingenuity. You are completely free to adapt this material or disregard it in favour of your own approach. However, you should keep the training objectives in the forefront of your mind to ensure that they are achieved - by whatever means you choose. The complementary notes at the end of this guide are provided to give you, the instructor, sufficient background information to feel confident to deliver the lesson. As a consequence, you will find more information than you are expected to present; however, the material will give you some armour against the more searching questions that might arise in the course of the lesson. GENERAL APPROACH TO LESSON Introduction. Before I move on to discuss this lesson itself, I thought it would be useful to spend a little time talking about how you might wish to approach instructing. Learning is essentially the acquisition of something new, or the enhancement of existing skills and knowledge. It is a relatively permanent change in how we act, feel and what we know. Your role as an instructor is to facilitate the swift transfer of information, which is understood by the students and can be applied in familiar and novel situations. Perhaps the most important consideration when teaching adults is motivation. Adult learners need to understand the importance and relevance of what they are to be taught and will expect their previous knowledge, experience and opinions to be drawn on and respected. The class will easily detect and respond to your attitude, energy and enthusiasm – it is usually mirrored. I would therefore advise you to be positive and encourage students to ask questions and express ideas and opinions. Simply establishing a good rapport with your students can assist learning. Contributing factors include good eye contact and a patient, supportive manner. The Lesson. In order to generate and sustain class interest, this lesson will follow a well-tested 3-section format. The first part is the Introduction, during which the need for the subject is introduced and the objectives outlined. The second section is the lesson Development. This is the substance of the lesson, in which the key points are introduced in a logical sequence and questions and discussions are used to develop new material. During the final section, Consolidation, the objectives are reviewed followed by testing questions to check understanding. Leading a Discussion. The main aim of a discussion is to collectively draw out ideas, knowledge and opinions relating to the subject. It is used to examine a problem, seek information or to enquire into a matter. The subject is introduced or the question posed by the instructor. Opinions are then aired, information exchanged and questions asked as the matter is probed from all angles. Your role as an instructor is to keep the discussion going by posing questions, clarifying students’ answers, encouraging all to contribute (control those who attempt to dominate every discussion and draw in those who are overly reticent) and generally controlling the procedure. Throughout, collate the points/conclusions from the class and summarise at suitable intervals. At the end of the discussion, pull together the main points and place the findings in the context of the overall lesson. 1 ACTION-CENTRED LEADERSHIP, TRANSACTIONAL/TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP, & RAF LEADERSHIP ATTRIBUTES OUTLINE Training Objectives: At the end of the session, Cohort members should be able to: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Describe the purpose of leadership Explain John Adair’s 3-ring leadership model Define the functions of a Leader Differentiate between Transactional and Transformational Leadership styles Give examples of the appropriate use of transactional and transformational approaches Describe the attributes required of RAF Leaders Attitudinal Goals: Cohort members should accept the value of transactional leadership to the establishment of committed, sustainable teams Training Resources: 1. 2. 3. AVTE Suite (PC, Projector). Power Point Presentation: Leadership One. Copy of Col Tim Collins 20 Mar 03 Speech (sufficient for one copy per student). Timings: The Session should be delivered in two 50-min sessions with a 20 min brake in between; total time: 2 hrs. There is a lot to cover – for bigger class sizes (in excess of 25) some of the tasks may have to be omitted – the point presented by the instructor in place of group activity. Block 1- Introduction. Block 2 – The notion of leadership. Block 3 – Functional Approach to leadership. Coffee BREAK Block 4 – Transactional/Transformational leadership. Block 5 – RAF Leadership Attributes. Block 6 – Consolidation. LESSON PLAN 2 GUIDE TIME HOW WHAT WHY BLOCK 1 - INTRODUCTION Briefly introduce self. 1 min Chat ‘I wonder why the study of leadership continues to attract so much interest? Ppt 2 ‘Certainly, people seem to spend a lot of time and effort writing about it’ ‘If you were to do a search for ‘leadership’ on Amazon at the moment, it reveal more than 18,000 titles – this is incredible. Reading one of these every day, it would take over 50 years to complete…’ 0.25 min Discussion ‘And leadership training courses cost in the region of £500 - £2000 a day – per individual! ‘Why do you think the study of leadership attracts so much attention? 4 mins Chat 0.5 min ‘Certainly for civilian organizations, leadership is associated with profits and competitive advantage….’ ‘For the military, leadership is linked with operational success – poor leadership has lead to loss of life (charge of Light Brigade) and loss of nations (many examples – Hitler is obvious).’ ‘At a lower level – and for all of us – poor leadership in the workplace can result in a miserable place to work…’ 3 This is your first question – use it encourage the class to start speaking. Once they find their voice, they will contribute more later. You are just seeking their general views, keep it positive, don’t draw conclusions. GUIDE TIME HOW Chat 1 min Chat Ppt 3 WHAT WHY ‘For us in the RAF, we rely on effective leadership throughout, at every rank level. A lot of money is therefore invested in providing formal training when individuals join and when they are promoted.’ ‘Leadership is not restricted to those who hold particular rank or appointments. The Service is in an era of great change and the operations in which we engage are less certain, less formulaic than ever in the past. The leadership demands faced by all of us are therefore more demanding and it is beholden on all of us from SAC to Air Chief Marshal to constantly question our approach and to learn and respond to changing circumstance and to be ready for novel situations.’ ‘This lesson is part of that questioning and revaluation process.’ ‘None of us can rest on our laurels – by so doing we are letting down those who rely on us.’ ‘This session provides elements of revision – for some – as well as introducing a couple of new ideas – for many. This is where you outline the scope of the lesson. 0.25 min [Briefly talk through the bullets on the Scope slide] 0.25 min 4 mins Ppt 4 ….Then …. Ppt 5 Ppt 6 Team Task BLOCK 2 – THE NATURE OF LEADERSHIP ‘Despite the large amount of research and the importance of the subject, it is remarkable difficult to define…’ SLIDE 5 [Get Class to work in groups of 3 – there is no need for them to move] Activity Pt 1– Ask groups to make a list of 5 famous leaders whom they consider great. 4 This will get the class to start thinking about what leadership is and what it is that make certain individuals ‘great’ leaders. GUIDE TIME HOW WHAT Team Task Now ask groups to think about the leaders they have listed and to list qualities that the leaders had in common that made/make them good leaders. Discussion [Give each group a couple of minutes each to present back to the class] Ppt 7 [Use this slide to summarize some of the points made by the class] ‘What constitutes a good leader has as much to do with our perceptions’ 5 mins 6 mins ‘Some people will define a leader by what he/she does, others by how they do it; others by the position the leader holds, and others by who the individual is (perhaps their relationship to a powerful person) 3 mins [Try to place the examples the class gave under one or more of these headings] ‘These perspectives on leadership are reflected by some of the more famous commentators….’ Ppt 8 Sir John Harvey-Jones (Ex Chairman of ICI & Management Guru) Leadership about results? Ppt 9 Sir Winston Churchill Leadership about process? 0.25 min 2 mins 5 WHY Each will have come up with different qualities. Examples include: Drive/enthusiasm; honesty/integrity; reliability/dependability; fairness; comm. skills; people skills; decision making; confidence; vision; humour. GUIDE TIME HOW WHAT Ppt 10 Field Marshal Slim Leadership about process? Ppt 11 Lao Tzu (Chinese Tauist Philosopher c600 BC) Leadership about position? Ppt 12 Gp Capt Sir Leonard Cheshire Leadership about the person? Ppt 13 ‘The RAF Leadership Centre was established a little over a year ago, and has taken a little of all of these to provide the following definition [SLIDE]’ 0.45 min ‘Also provided are a set of defining characteristics’ Ppt 14 0.5 min WHY Characteristics: Persuasion Example Integrity Inspires Develops Takes lead when things are difficult ‘As much as good leadership might be recognized, perhaps more obvious is bad leadership. [David Brent quotes and picture – vague humour only….] Ppt 15 0.5 min BLOCK 3 – FUNCTIONAL APPROACH TO LEADERSHIP ‘For many this part will be revision’ ‘John Adair developed his thinking on the Functional Approach to leadership when he worked at the Military Academy at Sandhurst.’ ‘The Approach is also known as ‘Action-Centred’ leadership, and is the model most widely used for teaching practical leadership in the UK military – IOT, NCO promotion courses, etc.’ 6 Into to Functional Leadership GUIDE TIME HOW Chat Ppt 16 2.5 mins Chat Ppt 17 Team Task 1 min WHAT WHY ‘The underlining principle of functional leadership is that if an individual acts like a leader – that is, does all the things that a leader should (functions – then by default they are the leader.’ ‘Most importantly, because all of the functions can be taught, Adair contests that leadership, itself, can be taught.’ ‘The approach suggests that the effectiveness of the leader is dependent upon meeting three areas of need within the work group, the need to: Task Functions (needs) – define and achieve the common task. Team Functions (needs) – build and maintain the team. Individual Functions (needs) – satisfy and develop the individual within the team.’ ‘If you can imagine the circles changing in size depending on the situation; for example, if the team is working on a particular task and someone became injured, the individual circle would become much larger relative to the other two – unless achieving the task was so important that the individual had to be neglected for the good of the outcome – instances of this can be imagined in a military context, where it might be necessary to return to deal with a casualty after an operational engagement.’ ‘The SLIDE lists the six essential functions of a leader (at least according to Adair) [Split the Class into 4 groups. Give each group one each of the 4 Actions by the Leader listed below. For the Action that they have been given, ask them to list the type of activities the leader would undertake under the headings: ‘Task needs, Team needs, Individual needs. Before giving them their Action, present the following as an example of what is expected:] 7 This will encourage the class to actually think about the model; rather than simply accepting it in the abstract. GUIDE TIME HOW Ppt 18 1 min Back to the Team Task 5 mins 10 mins Task Completion Ppt 19 Ppt 20 Ppt 21 Ppt 22 Ppt 23 0.25 min Ppt 24 Discussion 5 mins WHAT Action by the Leader: Devine Objective Task: Identify the problems and tasks; Identify constraints; Obtain available information. Team: Set targets; Involve the staff; Create team spirit. Individual: Assess individual skills; Examine your training programme; Set targets. Give one of the following Actions to each of the 4 groups to consider are: 1. Plan 2. Communicate 3. Support/control. 4. Evaluate. [Have each group present their answer in turn, after each one present the relevant SLIDE with the ‘pink’. In this sort of thing there is of course no definitive ‘pink’ only guidance. Be prepared to discuss their answer against the slide and draw comment from the class – but not for too long!] WHY This example will clarify what the groups are supposed to do. BLOCK 4 – TRANSACTIONAL/TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP ‘We have just discussed what a leader does…’ ‘But is simply performing a set of functions enough?’ ‘Surely there must be more to leadership then that?’ ‘Consider Ghandi and Stalin…’ ‘Presumably they each performed the leadership functions… although it accepted their priorities may not have been the same…’ [Encourage views from the class on the following questions – if opposing views are not presented from the floor, act a devil’s advocate to deepen the discussion.] Compare and contrast Ghandi & Stalin: ‘How committed do you think their followers were?’ ‘How much conviction did each generate?’ ‘How much of their message/philosophy/achievements remained after their deaths?’ ‘Why is there such a difference?’ 8 Presumably, the class will find that Ghandi’s legacy is greater than Stalin’s. He inspired his followers, who believed in him and his message through a conviction for a shared better future – for all. Stalin imposed his views and led through fear. GUIDE TIME HOW WHAT WHY Ghandi’s followers were prepared to lay down their lives for him; Stalin was prepared to take the lives of his followers. Chat Chat ‘These are extreme examples, but to a lesser degree, perhaps, they serve to show how important the leader’s approach is, specifically in his or her attitude to subordinates/followers.’ ‘‘Transactional’ and ‘transformational’ may sound like over-technical terms, but they do help sum up two quite different approaches to leadership.’ ‘Put simply, ‘Transactional’ describes a style of leadership in which the leader offer/provides some form of reward in exchange for followership; eg, pay, status, keeping job, security…’ 2 mins Chat Ppt 25 1.5 mins ‘A ‘Transformational’ style is more about engaging with followers/subordinates to inspire and motive them to want to perform/achieve.’ ‘It’s important to recognize that both styles can and are effective under the right circumstances – there are also instances when elements of both approaches may be successfully employed.’ ‘However, on balance, in developing people and organizations over the longer term and introducing major (transformational) change, a transformational style is likely to generate the greater chance of success and greater commitment and satisfaction from all those involved.’ ‘Lets look at each in just a little more detail….’ Transactional – [Go through each of the self-explanatory bullets on the SLIDE] 9 GUIDE TIME 1.5 mins HOW WHAT Ppt 26 Transformational – [Go through each of the self-explanatory bullets on the SLIDE] Task [Split class in to 5 or 6 groups – hand out a copy of Col Tim Collins’ speech ‘Our Business Now is North’ to everyone] Task Complete [Ask the groups to identify: 1. Elements of transactional and transformational leadership of the speech 2. The effects that those elements would have had on the troops 3. What leadership characteristics did Col Collins evidence] [Have each group present their findings to the class – a good technique is to ask one group to present their answer to, say question 1, the next to answer question 2, etc… and go around all the groups in that fashion… Finish by asking all the groups if they had an answer which hasn’t been mentioned by the other groups] Summary of task Ppt 27 [The leadership characteristics identified in the task should align with the characteristics listed on this SLIDE] 10 mins 10 mins [Go through each bullet and refer to various answers provided by the class during the task] 5 mins Ppt 28 ‘Perhaps bearing in mind what impact our actions have on our colleagues, subordinates and even our own leaders is not a bad starting point…’ BLOCK 5 - RAF LEADERSHIP ATTRIBUTES Instructor instructions [This is pretty much taught – with little intervention from the class. All you are expected to do is to briefly outline each attribute such that the students have a ‘sense’ of the type of leader we should all aspire to be.] 10 WHY What should develop is that the vast majority of this speech – on the eve of battle in which young, scared soldiers are presenting their lives for a cause they may not understand – is transformational This will consolidate the differences between transactional & transformational approaches and should leave a strong impression of the potential benefits of transformational leadership GUIDE TIME HOW Ppt 29 1.5 mins Ppt 30 1 min Ppt 31 1 min Ppt 32 1 min Ppt 33 1 min Ppt 34 1 min Ppt 35 1 min WHAT ‘This part of the lesson introduces the attributes that RAF leaders should have – or at lease aspire to have. In a rapidly changing world in which military tasks, equipment and way of operating is exposed to extreme transformation, there are escalating demands on every level of leadership from every trade and Branch.’ ‘The attributes required/expected of RAF leaders are summarized by the list on the SLIDE’ ‘Each will be described very briefly – you are not expected to remember all the detail, just the general meaning.’ Warfighter/Courageous – Main Points: - Warfighter first – state of mind as much as what we do - Military minded (uniformed civilians is a luxury we cannot afford!) - Physical and Moral courage Emotionally Intelligent – Main Points: - Know yourself, know others - Understand how you affect others - Recognize own and others’ areas to improve - Requires good interpersonal skills Emotional Intelligence can also be expressed by diagram on SLIDE Diagram shows how level of awareness (self and of others) impacts on actions – ultimately leading to having a positive impact on others… Flexible and Responsive – As Charles Darwin noticed: ‘It is not the strongest, but those most able to adapt who survive.’ Willing to Take Risks – Main Points: - Understanding risk and its management is vital to good decision making - Requires sound and timely judgement - Without taking (appropriate) risk little can be achieved - Leaders must encourage a culture that is not risk adverse – this requires trusting and supporting your subordinates 11 WHY GUIDE TIME HOW Ppt 36 1 min Ppt 37 WHAT Able to Handle Ambiguity – Main Points: - This is linked to flexibility and responsiveness, mental agility and the willingness to take risks. Mentally Agile, Physically Robust – - This pretty much speaks for itself 1 min Ppt 38 1 min Ppt 39 1 min Politically and Globally Astute – Main Points: - Must understand the application of air power, its advantages and limitations and be able to explain to own service subordinates and triservice colleagues and superiors - Need to be able to relate the advantages, disadvantages and limitations of air power in the context of the political circumstances being considered Technologically Competent – Main Points: - The RAF is and has always been at the forefront of technology - We must ensure that we stay up to date with emerging technology - This requires continual learning Ppt 40 Able to Lead Tomorrow’s Recruit – Main Points: - New generations bring new attitudes and new qualities - Leaders must understand and empathise with these - Embedded in each generation are our leaders of the future Ppt 41 ‘Children today are tyrants. They contradict their parents, gobble their food, and tyrannize their teachers’. (Socrates - 469 BC - 399 BC) 1 min 0.25 min BLOCK 6 – CONSOLIDATION Ppt 42 [The point of the objectives review is just to look back over what the lesson has covered] 12 WHY GUIDE TIME HOW Ppt 43 A/R WHAT [This is the scope SLIDE – use what ever time you have left to go through the list – if you have a lot of time (I doubt it) pick on individuals in the class and ask questions relating to each topic covered THE END 13 WHY INSTRUCTOR’S BACKGROUND READING/THEORY LEADERSHIP INTRODUCTION Leadership has been described as, ‘one of the most observed and least understood phenomena on earth’ (James McGregor Burns, 1978). Indeed, over 3000 new books are published on the subject each year in America alone. A trawl for ‘leadership’ on Amazon.co.uk in August 2005 produced 18,362 titles – if you were to read one of these every day it would take over 50 years to get through them all! But why is the subject so seductive? In the highly competitive Civil Sector, panning the ever-growing river of research and commentary to filter out the quintessence of leadership is part of a crusade for competitive advantage. For the military, it is an essential constituent for operational success and strategic advantage. That so much analysis, research and speculation has been undertaken on the subject points to its complexity. The thing is, leadership – both good and bad – is eminently recognizable when confronted. Yet it cannot be cornered; it is illusive: it is corporeal and intangible, subtle and bullish, kind and tyrannical, inspirational and dictatorial. Without wishing to pursue this line much further, it seems that leadership cannot exist in the abstract, rather it occurs in relation to or as a response to something. It is unsurprising, therefore, that none of the various trait, style or contingency theories has received unanimous acceptance and that the debate over whether leadership is trainable or innate remains unresolved; for leadership finds its meaning through its interaction with the environment. Whereas management is about the very challenging activity of unravelling organizational complexity, leadership produces change - that is its primary function. It would be magnificent hubris for this lesson to claim to provide all the answers to the leadership conundrum – or indeed any of them. Its aspirations are humble – yet important. Poor leadership produces poor results, at its most benign life becomes somehow more miserable for those affected, at its worst it can result in catastrophe. Against an increasingly volatile geopolitical backdrop, rapid technological, doctrinal and cultural changes require active, insightful and adaptive leadership. At home and away, RAF commanders at all levels and from every background are facing evermore complex, unfamiliar and fluid challenges, which are making the most taxing and profound demands of their leadership. This lesson does not delve the depths of academia, rather is provides a brief exploration of what the class understands by the notion of leadership to provide a starting point. John Adair’s functional leadership is then revised – this is the foundation framework adopted by the RAF for training junior leaders. The next part of the lesson introduces transformation and transactional leadership styles. Although sounding terribly scientific, these are simply alternative approaches to the exercise of leadership, which when understood will expand the options available to the practitioner. Finally, the lesson reviews the attributes expected of RAF leaders. 14 Leadership – Potted Theory It would make for a neat start to this section if I could provide a unifying definition of leadership, but the subject simply is not that tidy. For example, some might conclude that leadership is all about results: it is therefore what you achieve that makes you a leader. Others might argue that it is how you get things done that make you a leader. Yet others may determine that the leader is defined by the position they hold or even the person they are. Perhaps there is something in all of these viewpoints. Anyway, here is a little history on the development of thinking around the notion of leadership. I said in the introduction that there are literally tens of thousands of books on the subject; I have only included a couple of headlines – believe me, it is tortuous enough without further expansion. In essence, there are early theories that relate leadership to personal characteristics or traits, there are later ones that explore style and behaviour to guide the exercise of leadership, and there are those that suggest that the situation or environment should be examined to determine the appropriate leadership style. As much as I am convinced that each theory is partially correct, so am I certain that each is partially incorrect. Regrettably, I am undecided over which is which. Before the 1930s,‘…it was widely believed that leadership was a property of the individual, that a limited number of people were uniquely endowed with abilities and traits which made it possible for them to become leaders. Moreover, these abilities and traits were believed to be inherited rather than acquired.’ (Douglas McGregor in The Human Side of Enterprise). Research therefore concentrated on identifying the supposed universal characteristics of leadership. It was assumed that it would be possible to identify and isolate a finite set of these traits, which could be used when selecting and promoting individuals to leadership positions. This search was strongly influenced by the ‘great man’ theory that focused on how (primarily male) figures achieved and maintained positions of influence. The assumption was that these people were born to be leaders and would excel by virtue of their personality alone. Many researchers have sought to identify a definitive list of the requisite traits; however, comparison of the research finds only marginal convergence and production of a unifying list of all the identified traits generates a list that grows impossibly long. Furthermore, it does not follow that because a particular leader possesses a specific trait that someone else possessing the same trait would also go on to be a great leader. It is now widely accepted that no definitive set of leadership traits will ever be identified. However, some weak generalization may exist. For example, it has been found (Shaw (1976), Fraser (1978)) that leaders tend to score higher than average on scores of ability (intelligence, relevant knowledge, verbal facility), sociability (participation, cooperativeness, popularity), and motivation (initiative and persistence). Perceptions were drastically changed by World War II, which very publicly proved that leadership acumen was not the unique privilege of the few. After the War, industry wasted no time in seeking to apply the lessons of leadership to the management of their business. Business and military leaders certainly have one great attribute in common: they are visible. Lord Nelson, for example, on the deck of HMS Victory; Montgomery touring the units of the 8th Army before Alamein. Not for them the safety of the admiral’s cabin or the equivalent of a First World War general’s château behind the lines. Similarly, chief executives who make a difference – Sir Richard Branson, Sir Alan Sugar – rarely sit in panelled offices, but ‘manage by walking around’, talking, listening and winning hearts and minds. There is a broad consensus on a number of other essential qualities. Energy, stamina, vision, self-confidence, imagination, daring, ability to tolerate stress, adaptability and political acumen would appear in a list that few would contest. In many ways the personal characteristics typical of a leader 15 have changed remarkably little since Nelson, whose contemporaries praised his enthusiasm, ability to create harmony of purpose, to inspire confidence and to communicate well. John Adair wrote of Nelson: ‘He gave clear directions; he built teams, and he showed a real concern for the individual. …it also became clear that he possessed a leader’s gift for drawing out the best from people.’ Another inspirational quality was his willingness to share the privations of his men, telling the surgeon at Aboukir Bay who broke off from attending a wounded sailor to treat Nelson’s injured eye, ‘No, I will take my turn with my brave fellow.’ The concept of the leader has, however, undergone come significant changes since the post-war era. The notion of the ‘great man’ typifying the absolute in leadership has given way to a more inclusive style, which draws on the strengths of the whole team. There are many theories based on style and behaviour that seek to guide leaders. Interest in the approach largely arose from the work of Douglas McGregor in the 1960s. He proposed that management and leadership style is influenced by individuals’ assumptions about human nature. He provided two contrasting viewpoints: Theory X leaders take a fairly negative view of human nature, believing that the average person inherently dislikes work and is indolent; leaders holding this view believe that coercion and control is necessary and that workers have no desire for responsibility. Theory Y leaders, on the other hand, believe that the expenditure of physical and mental effort in work is perfectly natural and that the average human being, under proper conditions, learns not only to accept but to seek responsibility. Such leaders will endeavour to enhance their team’s capacity to exercise a high level of imagination, ingenuity and creativity. Another example from the behavioural school is found in Blake and Mouton’s research, again from the 1960s. They explored the degree to which managers and leaders were concerned with achieving the task (production) and/or concerned for employees (people). They argued that a propensity for either production or people to the exclusion of the other, or low arousal in both, was destructive - rather, a high concern for both production and people produced the most effective type of leadership behaviour. Most researchers today conclude that no single leadership style is right under all circumstances. One of the most profound breakthroughs in leadership theory remains that of James McGreagor Burns, who worked for John F Kennedy in his presidential campaign. Burns explained that most leaders are ‘transactional’ with their followers; that is, they offer something in exchange – jobs or some other benefit in return for allegiance. ‘Transformational’ leadership is of a different magnitude. ‘Transforming leadership, while more complex than transactional leadership, is more potent,’ wrote Burns. ‘The transforming leader recognizes an existing need or demand of a potential follower. But, beyond that, the transforming leader looks for potential motives in followers, seeks to satisfy higher needs, and engages the full person of the follower.’ There are very many great quotes that seem to encapsulate the essence of leadership – or a least part of it: I like these: ‘A leader is best when he is neither seen nor heard. Not so good when he is adored and glorified. Worst when he is hated and despised. Fail to honour people, they will fail to honour you. But of a great leader, when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, the people will all say: “We did this ourselves.”’ (Lao Tzu, Chinese Tauist Philosopher, c600 BC) ‘Leaders there have to be, and these may appear to rise above their fellow men, 16 but in their hearts they know only too well that what has been attributed to them is in fact the achievement of the team to which they belong’ (Gp Capt Geoffrey Leonard Cheshire VC DSO** DFC). ‘Leadership is that combination of example, persuasion and compulsion that makes men do what they don’t want to do: in effect it is the extension of personality.’ (Field Marshal Slim) ‘Leadership is the intelligent use of power’ (Sir Winston Churchill) ‘Leadership is about getting extraordinary results from ordinary people.’ (Sir John Harvey-Jones) The Functional Approach to Leadership John Adair developed his thinking on Functional Leadership whilst working at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst. Although his model has been widely adapted and reproduced in various guises, it is explained by his seminal text, ‘Effective Leadership’ (1983). Resting on the assumption that it is what leaders do that sets them apart, his ‘action-centred leadership’ focuses attention on the functions of leadership. As the functions may be learnt, he asserts that leadership itself can also be learnt. Adair believes that leadership is more a question of appropriate behaviour than of personality. He describes the effectiveness of the leader as being dependent on meeting three areas of need within the team. These are represented by three overlapping circles, which depict: Task Functions: To define and achieve the task. Team Functions: The requirement to build and maintain the team. Individual Functions: To satisfy and develop the individuals within the team. Depending on prevailing circumstances, the leader will constantly make judgments to prioritise between the three areas. Factors to consider (in no particular order) include: Task Functions Achieving the task objectives Defining group tasks Planning the work Organizing duties and responsibilities Allocating resources Controlling quality Checking performance Reviewing progress Team Functions Building team spirit Maintaining morale Ensuring cohesiveness of team Establishing systems of communications Maintaining discipline Setting standards Training the team Appointment of sub-leaders Individual Functions Meeting the needs of individual members of the team Giving praise and status Reconciling conflict between group and individual needs Attending to personal problems Training the individual 17 Task needs Team maintenance needs Individual needs Adair determined that there were six essential leadership activities: Defining the objective. Planning. Communicating. Supporting/Controlling. Informing. Evaluating. The table below illustrates these activities against task, team and individual needs. The suggestion being that an effective leader will satisfy all three interrelated area of need. Actions by the Leader Area of Need Team Task Identify the problems and tasks. Identify constraints. Obtain all available information. Establish your resources and priorities. Make your decisions. Set targets. ‘Involve’ the staff. Create team spirit. Examine structure and job allocation. Delegate. 3. Communicate Brief the staff. Check their understanding of your briefing. Have regular consultation with staff. Obtain and examine the feedback. Test ideas. 4. Support/Control Monitor progress being made. Check to see that your standards are being maintained. Review the task and your functions. Re-plan and carry forward incomplete targets if necessary. Co-ordinate the work. Reconcile any conflict. 1. Define objectives 2. Plan 5. Evaluate Acknowledge and reward success. Learn from any failure. Inform staff of results. Individual Assess individual skills. Examine your training programme. Set targets. Agee individual targets. Agree personal responsibilities. Delegate. Listen to the staff – ideas and troubles. Give advice when necessary. Show enthusiasm. Examine your own attitudes. Recognize and give encouragement. Counsel. Personal appraisal. Give guidance and encouragement. Examine personal needs for further training. ‘Actions by the Leader in Action-centred Leadership’ from Palmer, S. People and Self Management, (Butterworth-Heinemann, 1988), p.85. 18 Transformational Leadership James McGregor Burns was the first to put forward the concept of ‘transforming leadership.’ To him, transforming leadership, ‘…is a relationship of mutual stimulation and elevation that converts followers into leaders and may convert leaders into moral agents’ (Burns, 1978). He went on to suggest that it, ‘…occurs when one or more persons engage with others in such a way that leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality.’ At the heart of this approach is an emphasis on the leaders’ ability to motivate and empower his/her followers and also the moral dimension of leadership. Burns’ ideas were subsequently developing into the concept of transformational leadership where the leader transforms followers: ‘The goal of transformational leadership is to ‘transform’ people and organizations in a literal sense – to change vision, insight and understanding; clarify purposes; make behaviour congruent with beliefs, principles, or values; and bring about changes that are permanent, self-perpetuating, and momentum building’ (Bass and Avolio, 1994). The transformational approach has been widely embraced within all types of organizations as a way of transcending organizational and human limitations and dealing with change. It is frequently contrasted with more traditional ‘transactional’ leadership, where the leader gains commitment from followers on the basis of a straightforward exchange of pay, security, etc in return for loyalty, reliable work, etc. The two approaches are contrasted in the table below; you will notice similarities with the common conceptualisations of ‘management’ versus ‘leadership.’ Transformational Leadership Builds on an individual’s need for meaning Is preoccupied with purposes and values, morals, and ethics Transcends daily affairs Is orientated toward long-term goals without compromising human values and principles Focuses more on missions and strategies Releases human potential – identifying and developing new talent Designs and redesigns jobs to make them meaningful and challenging Aligns internal structures and systems to reinforce overarching values and goals Transactional Leadership Builds on an individual’s need to get a job done and make a living Is preoccupied with power and position, politics and perks Is mired in daily affairs Is short-term and hard data orientated Focuses on tactical issues Relies on human relations to lubricate human interactions Follows and fulfils role expectations by striving to work effectively within current systems Supports structures and systems that reinforce the bottom line, maximize efficiency, and guarantee short-term profits The essence of transformational leadership is that it invokes a ‘higher purpose’ beyond contractual obligation or mere compliance through remuneration. ‘…the transforming leader seeks to engage the follow as a whole person, and not simply as an individual with a restricted range of basic 19 needs.’ (Bryman, 1992). On the basis of his research findings, Bass concludes that in many instances (such as relying on passive management by exception), transactional leadership is a prescription for mediocrity and that transformational leadership leads to superior performance in organizations facing demands for renewal and change. Most of the study to date has relied on Bass’ field work; however, empirical research has begun to corroborate his findings, which concluded that effective transformational leaders share the following characteristics: 1. 3. 5. 7. They identify themselves as change agents. They believe in people. They are lifelong learners. They are visionaries. 2. 4. 6. They are courageous. They are value-driven. They have the ability to deal with complexity, ambiguity, and uncertainty. Explanations of the RAF Leadership Attributes (Produced by the RAF Leadership Centre) Before moving to the leadership attributes, it is worth spending a line or two on the broad ‘Warfighter First, Specialist Second’ philosophy. It is founded on the cultural acceptance that what sets us apart, as members of the RAF, is that we may be called upon to deploy in support of operations. It is essential that we excel as specialists; however, we must never forget that our primary duty, irrespective of how distant this may appear, is to contribute to the application of Air Power to achieve precise campaign effects at range in time. Our contribution is most effective when we follow responsibility and lead inspirationally, as the situation demands. This ethos is fundamental to the success of the RAF and its ability to sustain its operational effectiveness. Warfighter, Courageous. Being a warfighter first is important, as it is the core business of the RAF to exploit the air environment for military purposes. All RAF personnel must be focussed on the organisation’s core business - to create precise campaign effects at range in time. There are more than 60 different career specialisations in the RAF used to provide expeditionary air power and every person engaged in those specialisations must contribute to the precise campaign effect at range in time that is required – in other words, they must be a warfighter. To do that well they will have to be highly skilled in their specialisation but focussed on the purpose of the RAF. They must all be military minded with a knowledge of air power and air warfare and of a determined fighting spirit, able to overcome the adversity of circumstance that any member of the RAF may be called upon to face on operations. The teams the RAF sends to carry out its mission cannot afford to have members that are unable to look after themselves in the field or unable to defend themselves should either circumstance be necessary. Furthermore, traditional RAF distinctions between those who fight and those who support are breaking down. Not only is the “support space” vital to the “battle space” but so is the “business space,” for example by providing urgent operational requirements. NEC and the advent of UCAVs bring personnel who are remote from the actual battlefield into direct contact with it. The need to understand the people ‘at the other end of the technology’ and to build trust within the extended teams to carry out the RAF core business has never been so great. Physical courage is necessary to face the circumstances of operations whether that be the lonely ‘2 o’clock in the morning’ courage or the maintenance of the esprit de corps of the close-knit team. The moral courage required of RAF leaders is linked to the integrity and ethics that all personnel need to 20 have to be part of a fighting force. Those that live the core values of the RAF will find the moral courage to do the right thing. That moral courage supports the trust that is vital to building effective teams both in the immediate environment and in the wider defence community. Without the deep and enduring trust, both up and down the command chain, Mission Command cannot work. A person with moral courage must understand and have confidence in their own moral framework and be able to recognise and intervene appropriately in, for example, harassment incidents. They must be able to provide constructive dissent at any level while understanding that, once a decision has been made, no matter what that is, they must assume personal responsibility for its implementation. This display of loyalty will be vital to the retention of team cohesion. They must have the strength of character to not give in to morally unjustified actions. Those who have moral courage will not only take responsibility for their own actions but also for the situation around them. They will act rather than avoid what may be uncomfortable. They will do the right thing rather than the easy thing. They will not abrogate their responsibility as a leader. Moral courage is linked to humility – the courage to admit one’s own mistakes and learn from them, to know one’s own weaknesses and be able to work to improve them. A leader with moral courage will have the humility to know and acknowledge that results are the achievement of the team even if the leadership of the team created the cohesion and vision that inspired it. Finally, moral courage is linked to emotional intelligence – the awareness of others as well as self-awareness. Emotional Intelligence. Emotional intelligence may be represented by the simple diagram below: Others Self Awareness Action Self Awareness Social Awareness Self Management Social Skill Positive Impact on Others Expressed differently, it may be thought of as knowing what makes yourself tick, knowing what makes others tick, knowing how you affect others and being able to manage relationships by using that knowledge. Emotional intelligence will be enable leaders to build teams which are inherently strong 21 with the best being delivered by every member. Emotionally intelligent leaders focus on personal development, recognising areas in others and themselves that need improvement and doing something about it. This directly supports those aspects of transformational leadership that deal with individual and team development. Emotional intelligence requires good interpersonal and communication skills to understand the needs of others; in particular, it requires an open mind and good listening skills. Listening to understand, not immediately mentally imbuing the speaker with your own opinion. Understanding the effect of your communication on them; not talking over them or finishing their sentence with your view and so intimidating them into silent agreement with you. By understanding others, an emotionally intelligent leader is able to use their strengths for the benefit of the team and the organisation. This is the basis of understanding diversity. The ability to develop a team that can create best effect, and not a team of likeminded individuals who may all fall into the same trap, takes emotional intelligence. An understanding of others combined with greater self control, allows a leader to create a supportive and productive working environment. One where the atmosphere does not depend on the mood of the leader and where everyone is valued for their contribution. Equally, an emotionally intelligent leader will ensure the accurate communication of their intent both up and down the command chain. Emotional intelligence supports the trust that it is necessary to engender to make Mission Command work; it helps in understanding what is a genuine mistake and in how to deal with that mistake in order not to destroy trust in the leader. Emotional intelligence is also linked to leading tomorrow’s recruit. Flexible and Responsive. The need for flexibility and responsiveness on operations is axiomatic, but the attributes are also linked to the leadership of change. Change, large and small, is now a permanent part of our lives as the RAF determinedly meets the challenge of remaining relevant in a world that itself is rapidly changing politically, economically, socially and technically. RAF leaders need a flexible and responsive approach, both seeing the needs of their own organisation and recognising, and even anticipating, the needs of the higher organisation for which they work. Aligning their own organisation to those higher needs and to the overall vision for the RAF may sometimes be difficult and uncomfortable, yet leaders need to be flexible enough to work with the higher vision in mind. They need to be responsive to the demands of their superiors and to understand their intent. The attribute is also linked to innovation and mental agility, to the creativity and “right brain thinking” required for imaginative solutions. Not all leaders will always have the innovative skills themselves to find the solutions but they must be flexible enough to exploit the innovation of their team and be responsive to others’ ideas rather than suppressive of them. [Dowding’s abnegation of self-sealing fuel tanks for fighters in the Battle of Britain1 is a good case in point from a man who otherwise made good use of other’s innovative ideas in nurturing radar and setting up the world’s first integrated air defence system based on network principles.] Leaders also need to be responsive to the needs and goals of those for whom they are responsible to continue to be able to align personal aspirations with organisational goals which are clearly linked to emotional intelligence and transformational leadership. They must also be prepared to see the opportunities that change brings and be able to deal with the discomfort that is associated with it. They must be responsive to those who are averse to change but prepared to deal firmly with them. Willing to take Risks. RAF leaders constantly need to make decisions in all facets of RAF business, on operations as well as in the office or in the hangar. Understanding risk and the management of risk is vital to good decision-making. Since information is being received all the time, judgement is needed to choose the moment for the decision. The decision must be made within the time that is necessary for it to be effective but it would be foolhardy to take a quick decision on poor quality information when more time is available. This is, in itself, a risk management process. Without 1 Twelve Legions of Angels – Air Chief Marshal Lord Dowding, Chap VII Why are Senior Leaders so Stupid? Published by Jarrolds 1946. 22 taking risks, little can be achieved therefore the RAF needs those who are willing to take risks. Yet to take a risk without understanding the consequences is to take an unnecessary gamble. Leaders need to understand the consequences of failure if risks are to be taken. Account must be made for other stakeholders in the consequences of risks coming home to roost. Risks are addressed by the management techniques of Treat, Tolerate, Terminate or Transfer and must be managed at the appropriate level. Inevitably, there will be times when leaders will have to make decisions based upon incomplete information. At these times they must understand the use of intuition, that subtle blend of professional knowledge and experience that allows them to make decisions based upon their feelings. This is strongly linked to emotional intelligence and accurate knowledge of themselves and the others upon whose opinion they will have to rely. Leaders must encourage a culture that is not risk averse, that leads to acceptance of the 80% solution in 20% of the time and that moves away from unnecessary ‘gold plating’. The culture must support the trust that allows and encourages subordinates to act rather than to consult, knowing that a failure to act is a more serious fault than making a genuine mistake. This is fundamental to Mission Command. Leaders must also be able to devolve decision making to lower levels without abrogating their responsibility for the decisions; this support to subordinates is vital for Mission Command to work effectively. They must also be able to deal with the consequences of risk – failure – in a reasonable way that does not break down the trust necessary for Mission Command to work. Even with the advent of NEC, leaders must understand that the trust they place in their subordinates’ ability to make decisions will remain fundamental in the quest to increase the speed of the decision-making cycle which will give the RAF the battle-winning edge. Willingness to take risks is linked to the ability to handle ambiguity. Mentally Agile, Physically Robust. Mental agility links strongly to flexibility and responsiveness. Innovation is necessary to stay ahead of the competition, to adapt to meet the challenges of a changing world, to accept the changes made necessary by new technology, even to see the potential of new technology. Mental agility is necessary to recognise innovation in others rather than dismissing good ideas as too ‘wacky’ to work. The wacky idea may just be the best one; Barnes Wallis’ idea to bounce a heavy bomb off the water is familiar to us all today but must have stretched the imagination of those who first heard it. Those who suppress innovation by their own lack of imagination or because they themselves did not think of the idea, will stifle the organisation for which they work. Mental agility is also strongly linked to problem solving and decision-making and, in turn, to the ability to take risks. Leaders need the mental agility to move confidently between concepts and to be able to apply those concepts to the physical world. They must understand the need for doctrine and be able to apply it, without allowing it to become dogma. The mental agility to see things differently also links to leading tomorrow’s recruit and to the ability to handle ambiguity. Particularly in the latter case, to have the mental agility to work through ambiguity and see the paths that others cannot and to be able to use ambiguity to your advantage is a major attribute for a leader. Physical robustness is a necessity for all military leaders as they must be able to withstand the physical rigours of operations without loosing their mental capacity; this links clearly to the warfighter attribute. The physical rigours of operations are not the only physical demands on a leader. Any leader in any sphere can find that the demands on their time wearing, they may have to be constantly available to give direction, to reassure their team or members of their wider organisation and feelings of constant responsibility can be draining. In short, the pressures of leadership can be very stressful and are often faced alone. In operations these problems can be increased tenfold. A leader who is not physically robust will not long survive 23 his tenure in good health. [ The example of Sir Peter de la Billiere during the first Gulf War. He exercised for 30 minutes every morning prior to starting work.] Able to Handle Ambiguity. The ability to handle ambiguity is clearly linked to flexibility and responsiveness, mental agility and the willingness to take risks. It is also vital in being politically astute. The operational friction that causes the fog of war is reasonably well understood; this creates ambiguity. The pace and complexity of modern warfare can also create ambiguity of its own. Consider the battle-space of the Gulf War in 2003; warfighting, peacekeeping and peace support operations were being carried out in one battle-space. This can create immense ambiguity for a leader who has to work within the moral framework expected of his forces in each of those types of operation, and they can be very different with very different imperatives. Certainly decisions will rarely be clear-cut in such a situation. Equally, politics, whether international or national, within a large organisation or in the office, are seldom straightforward. A leader must steer a path through the ‘shades of grey’, the ambiguity, that is morally acceptable and will gain the support of his or her team. At junior levels ambiguity has been ‘managed out’ of the system in the military for many years giving clear, unambiguous direction to our junior officers and NCOs that they could follow with impunity. That is no longer the case. Tactical decisions can have strategic effects and the junior personnel who make them must be aware of those effects. To make matters more complicated, actions that may be acceptable at one level of operations may not be at another. Certainly, in this age of open, media-examined military operations all personnel, no matter what their rank, will be held accountable. Though there should be less ambiguity at junior levels, leaders should not always attempt to remove it completely as to do so would risk the process becoming more important than the results. Furthermore, awareness of ambiguity at lower levels should lead to those who rise up the ranks being comfortable with it at the higher levels and so being able to exploit it when the opportunity arises. Ambiguity links strongly to ethical and moral issues, to integrity and moral courage and, hence, to the core values of the RAF. Politically and Globally Astute. The Oxford English Dictionary defines politics as: ‘the activities associated with governing a state and with the political relations between states’ as well as ‘activities concerned with using power within an organisation or group’. This is not the Machiavellian or sinister manipulation of power but the legitimate and proper influence in their workplace that every RAF leader must have. They must understand the application of air power, its advantages and limitations and be able to articulate that to their subordinates in a single Service environment and to their colleagues and superiors in a tri-Service environment, whether that be at the operational level of PJHQ, the political and strategic level of MOD or in the business space of DPA or DLO. To be able to be competitive for Joint appointments, RAF officers need knowledge and experience of the Joint arena. If RAF leaders do not have the proper understanding of air power and air warfare and the influence, mental agility, flexibility and innovation to apply that understanding in their workplace, RAF leaders and the RAF itself risks becoming irrelevant. Equally clearly, in the wider sense of national and international relations, RAF leaders increasingly need awareness of political issues. They need to be able to relate and articulate the advantages, disadvantages and limitations of air power to the context of the political circumstances being considered. But more importantly any RAF leader may find him or herself having to explain to others including, on occasion, the press, the use of air power and its consequences. An up-to-date awareness of global issues is vital as time may not be available to become an expert. Political and global astuteness links strongly to the understanding of air power and air warfare doctrine as well as Joint doctrine. It links to continual personal development and through-life learning and allows leaders to engage in transformational leadership through idealised influence and intellectual stimulation. 24 Technologically Competent. Air power is technologically driven. The RAF’s past successes have been based, at least in part, on the innovative use of the most up-to-date technology and all our specialists rightly take pride in their expertise in their chosen areas. RAF leaders need to go beyond this; they must be able to see the uses to which new technology can be put. They must not be seduced by the Luddite tendencies that wish to preserve the comfort of the status quo, nor must they risk everything on unproven technology that does not deliver. The technological competence of an RAF leader must allow them to see the use and application of technology even if it is not in their sphere of expertise. They must see the risks involved in its adoption yet always be open to innovative and unusual, but nevertheless effective, uses of that technology. NEC may be the greatest challenge in the near to medium future in that it will stretch all RAF leaders’ ability to harness its potential. In this way technological competence is clearly linked to the management of risk, mental agility, flexibility and the leadership of change. To remain technologically competent, an RAF leader must embrace lifelong learning and personal development. Able to Lead Tomorrow’s Recruit. The new generation of personnel recruited into the RAF may have different experiences and expectations but they have every bit as much potential as those who have gone before. It is the RAF leader’s responsibility to unlock that potential for the benefit of the individual and the organisation. Leading tomorrow’s recruit will require leaders to adapt and broaden their leadership style and approach to be able relate to a wider section of society than has been evident to date. It will require emotional intelligence, flexibility and mental agility as well as exemplifying the core values of the RAF. 25