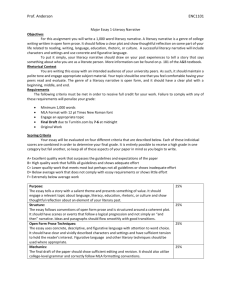

The Patient`s Story: Student Essays on Authentic

advertisement

Narrative Medicine: Student Essays on Authentic Environments and Personal Experiences Robert J. Bulik, Ph.D. The Family Home Visit program, a community-based experience for first year medical students during Block III of the Practice of Medicine I (POM) course, is designed to improve interviewing skills in a non-clinical setting, to foster the appreciation of patients as persons and not clients or diseases, and to understand how the family relates (interacts) to each other and how disease processes or medical conditions may affect the patient and family. One of the POM I course requirements and an expected outcome of the Family Home Visit is the Patient’s Story essay, written by students after visiting families in their homes and reflecting on the experiences (the “story”) of the individuals interviewed. This element of the curriculum relies on narrative “competence” or narrative medicine: “…the ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others”. While the medical case history and history of present illness are very good approaches to generating a differential diagnosis, some authors have pointed to the dehumanizing affect which results in objectifying the process and in “erasing” the connection between the individual and their disease.2 One approach to humanizing the physician-patient relations can be found in the nursing and allied health literature and centers on moving from simply patientstorytelling to student-created narrative. In developing a written narrative from what was heard (or left un-said), the student learns to hear the patient, thus creating a caring and healing environment within the doctor-patient relationship. The Patient’s Story has the following elements: Patient Home Visit – Patient Story Essay An essay, similar to a short story, contains several elements – an introduction, character development, setting description, and an interesting plot. Based on the elements of narrative medicine and active listening discussed in small groups, develop your patient’s Story from your home visit. In addition to the four elements of a short story, the importance to you of your patient’s story (meaning-making or interpretation), is an essential element that can be demonstrated in one of two ways within the essay – at the conclusion of each of the four sections as a transition to the next; or, as a separate section that provides a conclusion to your patient’s story. Introduction An introduction to an essay (or short story) sets the stage for the reader for the story. It provides more than a simple physical description; it establishes the context for your patient’s story. Character Throughout the story, the focus should remain on the character and their thoughts, actions, reflections, relationships, and history. Setting The four methods of direct character presentation are appearance, speech, action, and thought. If character is the foreground of your story, setting is the background – and as in a painting’s composition, the foreground may be in harmony or in conflict with the background. As you characterize your patient in terms of gender, race, and age, you need to also describe what environment she or he lives within. Plot A story can be considered a series of events recorded in their chronological order. A plot (as an element of the story) is a series of events deliberately arranged so as to reveal their significance to both the writer and the reader. Interpretation As author, reflect on similarities and differences between your own observations and patient’s descriptions, analyze family interactions, reflect on the influence of family on doctor-patient relationship, and reflect on the impact of insights gained on future clinical practice. In order to appreciate or at least understand someone else’s situation, we are sometimes advised to “walk a mile in that person’s shoes”. When we ask our medical students to conduct a family home visit, we hope they will come to appreciate the wide diversity of people and circumstances with which they will be working as practicing physicians – we are asking them to at least recognize the different “shoe sizes” that exist in all our communities. Charon R. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286:1897-1902. 2 Sobel RS. Recognizing the poverty of the medical case history. Acad Med 2000;75:85-9.