Narrative or Descriptive Essay/Epiphany

advertisement

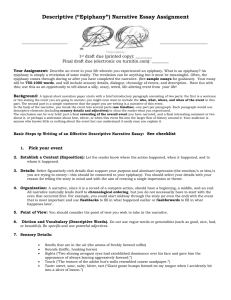

Narrative essay A substantial essay in the narrative mode which presents one or more events from your life, then uses those episodes to reach for explicit or implied insight, commentary, argument, epiphany, explanation, or some other high purpose. ► Offering your own experience for the edification of others is an arrogant act. It is usually best for the ethos to temper your story with humility, understatement, or modesty. ► If you must hold back or tinker with the truth to protect your reputation or cushion your ego, choose another topic. ► The event you describe from your life is evidence. It does not matter if that event is interesting in itself. In fact, events that are interesting in themselves tend to make bad essays. ► Unless you aim to make a point about victimhood, powerlessness, or fate, avoid incidents in which you had little or no control. Major things that happened to you are less interesting and valuable than little things you did. ► Grand events are so complex that they are difficult to grasp. Choose the minor things, small indicative episodes, odd little moments. The best essays create unexpected value from overlooked events. ► Choose an event that has a ‘before’ and ‘after’ that you understand and can describe. You must start and stop your narrative with efficiency. You will have to reduce and reorder events for the reader. ► You are telling a story about you. Assume a tone and voice that is honest. You will not be permitted to write in an affected, pompous, distant, or academic manner. ► Keep it recent. The longer ago, the less realistic the narration and the less believable the voice. Your narration must be sincere, believable, precise, definite, direct, confident, and clear. ► Look for the ways your ‘event’ must be reconsidered in the telling. Regardless of how sacred this event is to you, it must be flexible to drive a narrative essay. You may be required to divide it, sequence it, describe it as a cycle, start sooner or end later or vice-versa. You may be required to shift focus, fudge details, research particulars. ► If the event you choose does not hold the emotional power to generate a higher purpose—a higher purpose you can convey to a reader--you will have to scrap it. You will probably not be able to write to my standards without that emotional power. A process for establishing an idea: 1. Consider closely who you are: your virtues and vices, your strengths, your character. Choose a component of your personality that is important. Personality has a story; we are not just are. 2. Trace that component backward in your personal history to an event which altered it: made it grow, change, shift, begin, become clear. Because you are thinking about your history from a different angle, you should turn up different memories. 3. With the component in the back of your mind but unmentioned, tell the story of the moment. 4. Bring the component out in a discussion of how that moment changed who you are. Some suggestions for starting 1. Ignore the ‘higher purpose’ problem at first. Trust thyself: if you pick an important event, the higher purpose will be there—but only if you are honest and describe the event effectively. Start the essay as a narration alone; the rest will come. 2. Consider starting in in medias res. No introduction, no “David Copperfield crap.” (If you write it, I’ll probably make you cut it.) Imbed necessary basics. Challenge readers to work with minimal details—they like this, so long as there is a payoff. 3. Use your voice, your honest voice, and use it early. Be somebody real to the reader so the essay will draw strangers in. Live in the writing, don’t use it to hide. 4. Use the most powerful direct composition tool: dialogue. 5. Do not transition to discussion of a Big Idea. That’s likely to be ponderous and dull. Instead, bring the narrative to a “turn” where you step over the line into overtly describing a larger idea. Courageous writers will leave this ‘turn’ subtle or even unexplained; this will challenge the reader. Expand the epiphany into an insight. Generalize it into a broader comment on human nature into big ideas about universal experiences such as family and love and fear. In this selection, the ‘turn’ begins at the word ‘it’ at the start of the second sentence. A year later, I can still feel the grain of the concrete on my shoulder, still hear the sound of his voice. It is a strange thing how we blame things for what we ourselves have done. I suppose it is because things do not have their own order or power, their own memory; they can’t argue with us over their role. I didn’t get another bike. That’s not because I’m afraid still; truly, I wouldn’t use it much, now that I can drive. But the broader idea of the bike, which was so bright when I was 14, had been permanently, irreparably spoiled. And that wasn’t the only bright idea that didn’t survive.