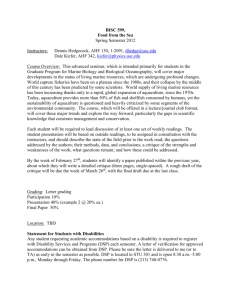

fishery sector review and future developments (fsrfd)

advertisement