Current Treatments of Agitation and Aggression CME

advertisement

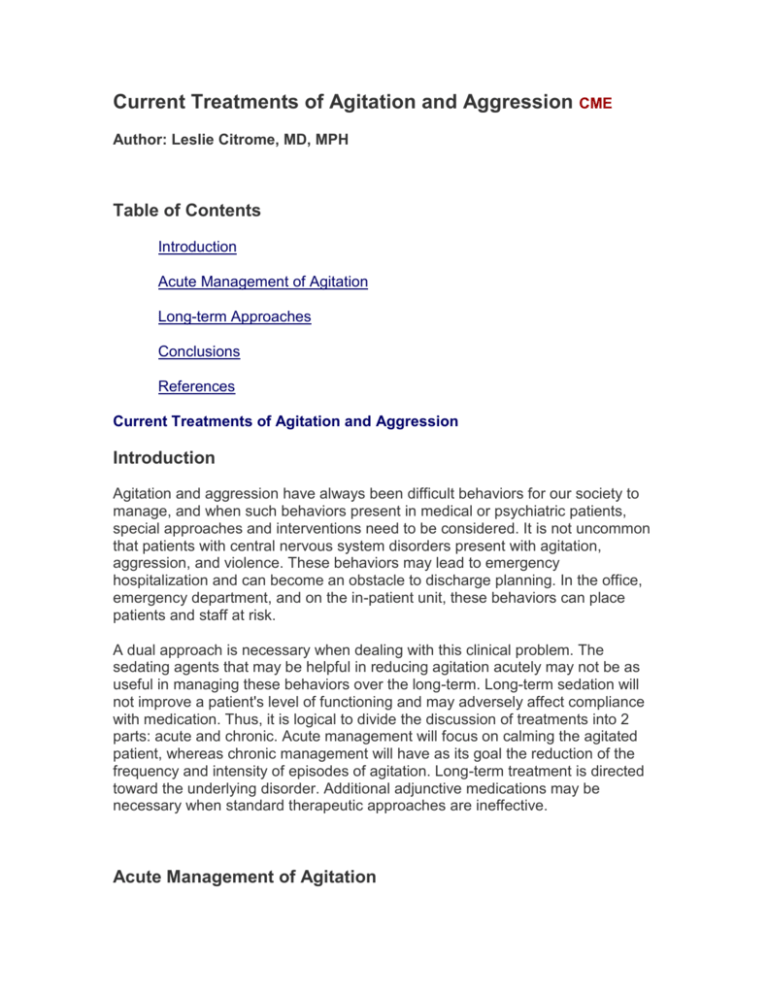

Current Treatments of Agitation and Aggression CME Author: Leslie Citrome, MD, MPH Table of Contents Introduction Acute Management of Agitation Long-term Approaches Conclusions References Current Treatments of Agitation and Aggression Introduction Agitation and aggression have always been difficult behaviors for our society to manage, and when such behaviors present in medical or psychiatric patients, special approaches and interventions need to be considered. It is not uncommon that patients with central nervous system disorders present with agitation, aggression, and violence. These behaviors may lead to emergency hospitalization and can become an obstacle to discharge planning. In the office, emergency department, and on the in-patient unit, these behaviors can place patients and staff at risk. A dual approach is necessary when dealing with this clinical problem. The sedating agents that may be helpful in reducing agitation acutely may not be as useful in managing these behaviors over the long-term. Long-term sedation will not improve a patient's level of functioning and may adversely affect compliance with medication. Thus, it is logical to divide the discussion of treatments into 2 parts: acute and chronic. Acute management will focus on calming the agitated patient, whereas chronic management will have as its goal the reduction of the frequency and intensity of episodes of agitation. Long-term treatment is directed toward the underlying disorder. Additional adjunctive medications may be necessary when standard therapeutic approaches are ineffective. Acute Management of Agitation Definitions Agitation can be defined as excessive verbal and/or motor behavior. It can readily escalate to aggression, which can be either verbal (vicious cursing and threats) or physical (toward objects or people). Technically, violence is defined as physical aggression against other people. The key to safety is to intervene early in order to prevent progression of agitation to aggression and violence. Table 1 shows the various pharmacologic options for acute agitation. Table 1. Pharmacologic Options for Acute Agitation -Intramuscular Agents Agent Dose (mg) Comments Lorazepam 0.5 to 2.0 Will treat underlying alcohol withdrawal. Caution: respiratory depression. Haloperidol 0.5 to 10 Caution: akathisia, acute dystonic reaction, seizure threshold decrease. Droperidol No FDA-approved psychiatric indication. Caution: prolongation of the QTc interval (removed from UK market, and new black box warning in United States) 2.5 to 5.0 Olanzapine* 10 (2.5 for patients with dementia) Superiority over haloperidol (schizophrenia) and lorazepam (bipolar disorder) in clinical trials. No EPS. Caution: weight gain over time. Ziprasidone* 10 to 20 Little or no EPS. Caution: prolongation of the QTc interval. *Intramuscular formulations not yet available in the United States as of May 7, 2002. FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; EPS, extrapyramidal signs and symptoms Environmental Interventions Environmental interventions include the removal of objects that can be used as weapons (ashtrays, chairs), making sure that other patients can safely go to another area (it is easier to move several calm patients than one agitated patient), and having several staff members available. Extraneous stimulation can often make things worse; thus, it is important to turn off the television if there is one in the day room or waiting room. Behavioral Approaches Behavioral approaches include never turning your back to an agitated patient, talking softly rather than shouting, and inquiring about what specific needs the patient may have. Eye contact may help establish rapport, but it may be necessary to break eye contact if it is making the patient uncomfortable. The tone of the intervention is set in the first few minutes. A genuine sense of concern goes a long way in reducing the occurrence of an assault. Innocuous questions that focus on basic needs, such as asking about appetite and sleeping patterns, can be helpful. The patient should be permitted to ventilate his or her feelings, but this may need to be cut short if the degree of agitation is escalating and there is clear danger to self and others. It is often helpful for the staff member who has the best rapport with the patient to interact with him/her. Figure 1 shows an algorithm for the management of the agitated patient. Figure 1. Managing the agitated patient. Medications: Issues in Assessment Early on, acutely agitated patients should be offered medication. The choice of medication will be dependent on several factors, notably history. An agitated patient on an inpatient unit whose history is well known will be managed differently from an acutely agitated patient brought in to the emergency department. The latter may be acutely withdrawing from alcohol or sedatives and, thus, require very different interventions from someone who is agitated because of a functional psychosis. Note that almost half of all patients with schizophrenia have a drug and/or alcohol abuse problem,[1] further complicating a differential diagnosis of the cause of agitation. There may be limited time to conduct a patient assessment. If someone is acutely agitated and is an immediate danger to self or others, emergency measures must be taken to avoid harm. Somatic/medical conditions must be ruled out prior to initiating additional treatment, as an underlying metabolic, toxic, infectious, or other nonpsychiatric cause may need to be treated. This is not as great a concern for the long-term patient whose history is well known to the staff as it is for the relatively unknown patient presenting to the emergency room. Mechanical restraints may be useful while the medical workup is being conducted. Risk assessment is important. Past history of violence may be the best predictor of future violent behavior.[2-4] Current ideation -- in particular, delusions -- has been linked to violence.[5,6] Sedation. Nonspecific sedation is often used in the management of an acutely agitated patient. In general, intramuscular injection of a sedative has a faster onset of action than oral or sublingual administration. Up to now, choice of intramuscular medication for behavioral emergencies has been limited to intramuscular preparations of typical antipsychotics (such as haloperidol or chlorpromazine) vs intramuscular preparations of benzodiazepines (principally lorazepam). The availability of intramuscular formulations of novel atypical antipsychotics will provide new treatment options for the management of acute agitation in patients with psychosis.[7] In general, the atypical antipsychotics are better tolerated than the older agents. Of importance is their decreased propensity for inducing akathisia -- a side effect of typical agents that has been associated with agitation and aggression.[8,9] In addition, these new formulations provide the opportunity for a smooth transition to oral dosing with the same agent once the acute agitation has been appropriately managed. Benzodiazepines: focus on lorazepam. Lorazepam, the only benzodiazepine that is reliably absorbed when administered intramuscularly, remains a rational choice when treating an acute episode of agitation, especially when the etiology is not clear, such as when a patient with a history of schizophrenia may actually be withdrawing from alcohol.[10-12] Lorazepam's half-life is short (10 to 20 hours) and its route of elimination produces no active metabolites. The usual dosage of 0.5 to 2.0 mg every 1 to 6 hours may be administered orally, sublingually, intramuscularly, or intravenously. However, respiratory depression may be a complication in vulnerable patients such as obese smokers with pulmonary disease. Lorazepam is not recommended for long-term daily use because of the problems associated with tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal. The concern over paradoxic reactions to benzodiazepines, as exhibited by hostility or violence, may be exaggerated.[13] Conventional antipsychotics. The typical antipsychotics cause sedation, given a high enough dose. Haloperidol, a high potency butyrophenone, has been frequently used as an intramuscular as-needed medication for agitation and aggressive behavior in an emergency department setting for a wide variety of patients, both alone,[14] and in combination with lorazepam.[15] However, haloperidol is no longer a reasonable choice for treating psychosis, given the problem of extrapyramidal side effects, tardive dyskinesia, and inferior efficacy compared with typical antipsychotics in patients with a history of suboptimal response to conventional antipsychotics.[16] Droperidol, another antipsychotic in the butyrophenone class, is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for psychiatric conditions but has been used for sedating agitated patients in an emergency room setting. [17] However, droperidol causes a dose-dependent prolongation of the QT interval,[18] and concern over this has led to the withdrawal of this product in the UK market, and a "black-box" warning in the United States. Olanzapine. Olanzapine, available in the United States since 1996 as an oral agent, is now available in fast-disintegrating tablet (Zydis), and the intramuscular preparation has been recommended for approval for the treatment of agitation in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and dementia. The main advantage of the intramuscular formulation is the very rapid achievement of a high peak plasma concentration, correlating with efficacy as early as 15-30 minutes postinjection. Half-life is the same as with oral dosing. Efficacy in controlling agitation was established in 4 double-blind controlled pivotal trials involving more than 1000 patients.[19] The majority of patients required only 1 olanzapine injection to control their agitation. Intramuscular olanzapine was superior to intramuscular haloperidol (in patients with schizophrenia) and intramuscular lorazepam (in patients with bipolar disorder) at the earliest time point measured. As expected, intramuscular olanzapine exhibited less extrapyramidal side effects compared with intramuscular haloperidol. The optimal dose appears to be 10 mg. However, for patients with dementia, the recommended dose is 2.5 mg. Starting oral olanzapine at 20 to 40 mg/day may result in the reduction of agitation that can be seen when patients initially present for treatment. Results of a multicenter study of a loading-dose strategy for olanzapine were recently reported, whereby patients were randomized to receive either up to 40 mg/day or up to 10 mg/day at the initiation of therapy (N=148).[20] Patients were enrolled with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar I disorder and were randomized to 4 days of double-blind oral olanzapine treatment administered by 2 different dosing strategies. One strategy was "Rapid Initial Dose Escalation" (RIDE), consisting of olanzapine 20 mg then 2 additional olanzapine 10 mg oral doses as needed (up to 40 mg/day) on days 1 and 2, followed by 1 additional olanzapine 10 mg oral dose as needed (up to 30 mg/day) on days 3 and 4. The other strategy was "Usual Clinical Practice" (UCP), consisting of olanzapine 10 mg then 2 additional lorazepam 2 mg oral doses as needed (10 mg olanzapine and up to 4 mg lorazepam) on days 1 and 2, followed by 1 additional lorazepam 2 mg oral dose as needed (10 mg olanzapine and up to 2 mg lorazepam) on days 3 and 4. After 4 days of double- blind treatment, all patients were treated openly with standard olanzapine doses (5-20 mg on days 5-7). Although improvement on measures of excitement occurred in both groups, RIDE dosing was significantly more effective than UCP (P = .019), and this difference was first significant at the 24-hour rating (P = .04). No significant differences between groups existed in treatment-emergent adverse events or potentially clinically significant laboratory abnormalities. Thus, it appears that in the acute care of the agitated patient, initiating olanzapine at a 20-mg dose followed if needed by further doses up to 40 mg/day in the first 1-2 days may offer clinicians a rapid and effective treatment strategy. Ziprasidone. Ziprasidone has been available in the United States since 2001. Although clinical experience with ziprasidone is more limited than with olanzapine, it is an option that may be helpful for selected patients. An obstacle for its use is the association with prolongation of the QTc interval. This issue has led to a warning on the product prescribing information sheet (package insert) that ziprasidone should be avoided in combination with other drugs that are known to prolong the QTc interval, in patients with congenital long QT syndrome, and in patients with a history of cardiac arrhythmias. For these reasons, ziprasidone treatment should only be started after an EKG evaluation if any risk factors are present. On the other hand, in contrast to other atypical antipsychotics (including olanzapine), ziprasidone has not been associated with weight gain over time.[21] Intramuscular ziprasidone has been recommended for approval for the control of agitation in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Peak plasma concentrations after an intramuscular dose of ziprasidone are achieved in 30-45 minutes (with half-life of 2.2 to 3.4 hours).[22] Efficacy was established in 2 double-blind controlled pivotal clinical trials involving approximately 200 patients. The recommended dose is 20 mg. [23] Overall, ziprasidone was well tolerated and almost free of extrapyramidal side effects, when given by intramuscular injection, at doses up to 80 mg per day. [22] Long-term Approaches Once the acute agitation is managed, longer-term strategies are required. Specialized units such as secure care or psychiatric intensive care units[24] can provide a structured environment that optimizes staff and patient safety. It is not unusual for overt physical aggression to be greatly diminished in such an environment, only to reappear in a more chaotic setting. Medication treatment remains the mainstay of therapy of persistent aggressive behavior. Choice of a first-line agent is dependent upon the specific underlying disorder. Additional adjunctive medications may be needed if monotherapy fails. Medications that have demonstrated efficacy in preventing or reducing the intensity and frequency of aggressive episodes include atypical antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and beta-adrenergic blockers. Serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors may also be helpful. Table 2 shows the pharmacologic options for persistent aggressive behavior. Table 2. Pharmacologic Options for Persistent Aggressive Behavior Class Comments Atypical antipsychotics Clozapine superior to risperidone and haloperidol. Mood stabilizers Limited evidence from randomized clinical trials, but more exists for valproate and carbamazepine. Beta-blockers Most evidence is from patients with organic mental disorders. Antidepressants SSRIs may be helpful -- one randomized clinical trial of adjunctive citalopram in schizophrenia. Caution: rapid cycling in patients with bipolar disorder. Benzodiazepines Negative trial of adjunctive clonazepam in schizophrenia is cautionary. Leads to physiologic tolerance over the long term. SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor A common theme may be the serotonergic system. A disturbance of this system has been implicated in impulsive violence in humans.[25,26] A disturbance of the serotonergic system has been inferred from low levels of the 5hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF),[27-30] or from a blunted response to neuroendocrine challenges.[31] This work was done largely in aggressive patients with personality disorders and substance use disorders. Atypical Antipsychotics The role of the serotonergic system in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia has recently received increased research attention, stimulated by the success of atypical antipsychotics that have serotonergic effects. However, there is only limited information on the serotonergic system and its functioning in aggressive patients with schizophrenia. Measures of serotonergic function in humans, such as the CSF 5-HIAA assays and neuroendocrine challenges, yield results that can be distorted by concomitant medication, including antipsychotics. The CSF levels of 5-HIAA in a small sample of aggressive schizophrenics (N=10) were not different from those obtained in matched controls.[32] In this study, the authors were unable to discontinue antipsychotic treatment of the subjects for an adequate period of time. This problem may have contributed to the negative result. However, in spite of the lack of specific information on the role of serotonin in aggression in schizophrenia, the serotonin hypothesis has been a theoretical mainstay of the antiaggressive treatment in this disorder. It has been observed that atypical antipsychotics, especially clozapine, appear to specifically target aggressive behavior. This has been demonstrated in several retrospective studies.[33-39] The reductions of hostility[40] and aggression[41] after clozapine treatment were selective in the sense that they were (statistically) independent of the general antipsychotic effects of clozapine. This was confirmed in a double blind 14-week randomized clinical trial comparing the specific antiaggressive effects of clozapine with those of olanzapine, risperidone, or haloperidol in 157 inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder with a history of suboptimal treatment response to conventional antipsychotics. [42] Clozapine had a significantly greater antihostility effect than haloperidol or risperidone. The effect on hostility was independent of antipsychotic effect on delusional thinking, formal thought disorder, or hallucinations, and independent of sedation. Neither risperidone nor olanzapine showed superiority over haloperidol. The failure of risperidone to demonstrate superiority to haloperidol in treatmentrefractory patients is in direct contrast to an earlier study with treatmentresponsive patients participating in a pivotal registration protocol.[43] Regardless of this, an important limitation shared by these 2 studies[42,43] is that subjects were not specifically selected because of a history of aggressive and hostile behavior, and that overt hostility was largely demonstrated by verbal expression of resentment rather than by overt physical assault. Quetiapine may also preferentially reduce hostility and aggression in treatmentresponsive acute schizophrenia. Utilizing the data gathered in a pivotal registration study, both quetiapine and haloperidol were found to be superior to placebo in reducing positive symptoms, but only quetiapine was superior to placebo in the measures of aggression and hostility.[44] This is supported by a case report describing a dramatic response to quetiapine monotherapy in a persistently aggressive patient who had failed to respond to numerous other medications.[45] Another post-hoc subanalysis, this time of olanzapine compared with haloperidol, was conducted using the data from a pivotal multicenter clinical trial that enrolled treatment-responsive patients.[46] Olanzapine-treated patients experienced a significantly greater improvement in behavioral agitation than did the haloperidoltreated patients. At this time, the weight of the evidence favors clozapine as specific antiaggressive treatment for schizophrenia patients,[47] with demonstrated superiority to haloperidol and perhaps risperidone. Mood Stabilizers Mood stabilizers are the drugs of choice in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Their efficacy in mood regulation, and perhaps in reducing impulsivity, has led to their use in other disorders, including schizophrenia. Such use has been increasing over time, and in one report of New York State Psychiatric Centers, in 1998, 2134 out of 4922 (43.4%) inpatients diagnosed with schizophrenia received a mood stabilizer, with valproate most commonly prescribed (1724 or 35.0%).[48] Expert consensus guidelines suggest the use of adjunctive mood stabilizers in patients with schizophrenia with agitation, excitement, aggression, or violence,[49] but there is little in the way of evidence in the form of randomized clinical trials for these patients. A recent review of the use of valproate to counter violence and aggressive behaviors in a variety of diagnoses[50] did reveal a 77.1% response rate (defined by a 50% reduction in target behavior) based on 17 reports (164 patients), but included only 16 patients with schizophrenia. Only 1 double-blind study was found, and it consisted of 16 patients with borderline personality disorder.[51] Since that review, there have been additional reports, including a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of valproate in 20 children and adolescents with explosive temper and mood lability where valproate was superior to placebo,[52] and a 1-year open-label prospective trial of adjunctive valproate with olanzapine in 10 patients with paranoid schizophrenia, demonstrating statistically significant reductions in hostility.[53] Recently completed is a large, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, clinical trial of adjunctive valproate in patients recently hospitalized with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia.[54] A total of 249 patients with schizophrenia were randomized to receive over a 4-week period either olanzapine and valproate, olanzapine and placebo, risperidone and valproate, or risperidone and placebo. Subjects were required to have a minimum threshold of certain symptoms (hostility and uncooperativeness, or excitement and tension). Monotherapy with an antipsychotic was compared with combination therapy with an antipsychotic and valproate. Adjunctive valproate was well tolerated and resulted in faster improvement in psychopathology (as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale), including positive symptoms. Valproate significantly enhanced antipsychotic efficacy as early as treatment day 3. This study is important because it is the first large-scale randomized clinical trial that focuses on valproate in schizophrenia. It is anticipated that this will inspire further work that will examine the use of adjunctive valproate on more refractory populations and over longer lengths of time. Adjunctive lithium has also been used for aggressive behavior. However, the data for the use of lithium in patients with schizophrenia is mixed. When lithium was added to antipsychotics for the treatment of resistant schizophrenic patients classified as "dangerous, violent, or criminal," no benefits were seen after 4 weeks of adjunctive lithium.[55] However, another group found that lithium was useful as a single agent in ameliorating psychosis in 3 schizophrenic patients who suffered from marked akathisia with accompanying agitation, restlessness, and irritability when on standard antipsychotics.[56] Carbamazepine may be a useful adjunct to antipsychotic therapy[57] and may lower aggression in a broad spectrum of disorders.[58] However, carbamazepine as an antiaggressive agent has been studied in only a limited number of patients.[59-65] The largest of these studies is a multifacility double-blind protocol comparing the effect of a 4-week trial of adjunctive carbamazepine vs placebo with standard antipsychotic treatment in 162 patients, 78% of them with a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition diagnosis of schizophrenia (the remainder with schizoaffective disorder), all with excited states or aggressive/violent behavior that responded unsatisfactorily to antipsychotic treatment.[64] There was no statistically significant difference in response among the patients with schizophrenia receiving either adjunctive carbamazepine or placebo, but a trend toward moderate improvement with carbamazepine was noted (P < .10). An empirical trial of adjunctive valproate, lithium, or carbamazepine may be considered for patients with schizophrenia and persistent aggressive behavior, but chronic use, without demonstrable benefit, only exposes the patient to the possibility of side effects. Beta Blockers Beta-adrenergic blockers -- in particular, propranolol -- have been used in the treatment of aggressive behavior in brain-injured patients [66,67] and, to a limited extent, in schizophrenia.[68] A chart review of chronically assaultive schizophrenic patients receiving nadolol or propranolol revealed a 70% decrease in actual assaults for 4 of the 7 patients.[69] A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive nadolol (40-120 mg/day) in 41 patients, 29 of whom were schizophrenic, found a decline in the frequency of aggression compared with controls.[70] In a report of a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive nadolol (80-120 mg/day) in 30 violent inpatients, of whom 23 were schizophrenic, a trend was found demonstrating lower hostility for the active treatment group.[71] Benzodiazepines Despite a positive anecdotal report demonstrating the usefulness of adjunctive clonazepam in reducing aggression,[72] a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive clonazepam in 13 schizophrenic patients receiving antipsychotics revealed no additional therapeutic benefit; in fact, 4 patients demonstrated violent behavior during the course of clonazepam treatment.[73] This finding is in contrast to the clinical utility of clonazepam in carefully selected patients with bipolar disorder. Although the consensus guidelines recommend continued use of lorazepam for patients with schizophrenia with agitation or excitement (but with no history of substance abuse),[49] such use can be problematic because of physiological tolerance. Missing scheduled doses of lorazepam may result in withdrawal symptoms that can lead to agitation or excitement, as well as irritability and a greater risk for aggressive behavior. Antidepressants Impulsive aggression against self and others may be influenced by effects on serotonin (5-HT) receptors. Specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been reported to be useful in reducing aggression. In a retrospective, uncontrolled study, adjunctive fluoxetine was given to 5 patients with chronic schizophrenia with a decrease in violent incidents observed for 4 cases.[74] In another case report, fluvoxamine added to risperidone was reported to be effective in managing aggression in schizophrenia.[75] A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study of adjunctive citalopram in violent patients with schizophrenia found that the number of aggressive incidents decreased during the active citalopram treatment.[76] Care must be taken when prescribing antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder, as they may precipitate mania or lead to rapid cycling. Adjunctive Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) Adjunctive ECT may be helpful in patients who have inadequately responsive psychotic symptoms.[77] An open trial of ECT in combination with risperidone in male patients with schizophrenia and aggression resulted in a reduction in aggressive behavior for 9 of the 10 patients.[78] In a case report of a patient with treatment-resistant schizophrenia receiving adjunctive ECT (together with clozapine and olanzapine), the authors reported a significant amelioration of aggressive behavior (Greenberg et al., unpublished data, 2002). Conclusions The treatment of agitation, aggression, and violence begins with the successful management of the acute episode, followed by strategies designed to reduce the intensity and frequency of subsequent episodes. Short-term medication therapies include the use of lorazepam and/or antipsychotics. Intramuscular preparations of atypical antipsychotics are an improvement over what has been available. Lorazepam for long-term daily use is not recommended because of problems associated with tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal. Long-term treatment is directed toward the underlying disorder. When standard therapeutic approaches fail, adjunctive medications can be considered. Clozapine appears to be the most effective antipsychotic in reducing aggression in patients with schizophrenia. Adjunctive mood stabilizers can also be used to decrease the intensity and frequency of agitation and poor impulse control. Adjunctive beta-blockers, serotonin specific reuptake inhibitors, and ECT may be considered for patients in whom other approaches have failed. References 1. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990;264: 511-2518. 2. Blomhoff S, Seim S, Friis S. Can prediction of violence among psychiatric inpatients be improved? Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1990;41:771-775. 3. Convit A, Jaeger J, Lin SP, Meisner M, Volavka J. Predicting assaultiveness in psychiatric inpatients: a pilot study. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39:429-434. 4. Karson C, Bigelow LB. Violent behavior in schizophrenic inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175:161-164. 5. Taylor PJ. Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:491-498. 6. Junginger J, Parks-Levy J, McGuire L. Delusions and symptom-consistent violence. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:218-220. 7. Citrome L. Aggression and intramuscular antipsychotics: new options for acute agitation. Postgrad Med. 2002; In press. 8. Keckich WA. Neuroleptics. Violence as a manifestation of akathisia. JAMA. 1978;240:2185. 9. Siris SG. Three cases of akathisia and "acting out". J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46:395-397. 10. Salzman C. Use of benzodiazepines to control disruptive behavior in inpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49(suppl):13-15. 11. Greenblatt DJ, Shader RI, Franke K, et al. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of intravenous, intramuscular, and oral lorazepam in humans. J Pharm Sci. 1979;68:57-63. 12. Greenblatt DJ, Divoll M, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. Pharmacokinetic comparison of sublingual lorazepam with intravenous, intramuscular, and oral lorazepam. J Pharm Sci. 1982;71: 248-252. 13. Dietch JT, Jennings RK. Aggressive dyscontrol in patients treated with benzodiazepines. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49:184-188. 14. Clinton JE, Sterner S, Stelmachers Z, Ruiz E. Haloperidol for sedation of disruptive emergency patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:319-322. 15. Hughes DH. Acute psychopharmacological management of the aggressive psychotic patient. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:1135-1137. 16. Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, et al. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:255-262. 17. Thomas H, Schwartz E, Petrilli R. Droperidol versus haloperidol for chemical restraint of agitated and combative patients. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:407-413. 18. Lischke V, Behne M, Doelken P, Schledt U, Probst S, Vettermann J. Droperidol causes a dose-dependent prolongation of the QT interval. Anesth Analg. 1994;79:983-986. 19. Eli Lilly and Company. Briefing Document for Zyprexa IntraMuscular (olanzapine for injection), FDA Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee, January 11, 2001 with Addendum February 14, 2001. Available at: www.fda.gov. 20. Baker RW, Kinon BJ, Liu H, et al. Effectiveness of rapid initial dose escalation of oral olanzapine for acute agitation. American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; December 2001. 21. Taylor DM, McAskill R. Atypical antipsychotics and weight gain--a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:416-432. 22. Pfizer, Inc. Briefing Document for Ziprasidone Mesylate for Intramuscular Injection, FDA Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee, February 15, 2001. Available at: www.fda.gov. 23. Reeves KR, Swift RH, Harrigan EP. Ziprasidone intramuscular 10 mg and 20 mg in acute agitation. Program and abstracts of American Psychiatric Association 151st Annual Meeting; May 30-June 4, 1998; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Poster NR494. 24. Citrome L, Green L, Fost R. Clinical and administrative consequences of a reduced census on a psychiatric intensive care unit. Psychiatr Q. 1995;66:209-217. 25. Apter A, Van Praag HM, Plutchik R, Sevy S, Korn M, Brown SL. Interrelationships among anxiety, aggression, impulsivity, and mood: a serotonergically linked cluster? Psychiatry Res. 1990;32:191-199. 26. Roy A, Linnoila M. Suicidal behavior, impulsiveness and serotonin. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;78:529-535. 27. Linnoila M, Virkkunen M, Scheinin M, Nuutila A, Rimon R, Goodwin FK. Low cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid concentration differentiates impulsive from non-impulsive violent behavior. Life Sci. 1983;33:2609-2614. 28. Virkkunen M, Linnoila M. Serotonin in early onset, male alcoholics with violent behaviour. Ann Med. 1990;22:327-331. 29. Virkkunen M, De Jong J, Bartko J, Linnoila M. Psychobiological concomitants of history of suicide attempts among violent offenders and impulsive fire setters. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:604-606. 30. Virkkunen M, Goldman D, Nielsen DA, Linnoila M. Low brain serotonin turnover rate (low CSF 5-HIAA) and impulsive violence. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1995;20:271-275. 31. Coccaro EF, Siever LJ, Klar HM, et al. Serotonergic studies in patients with affective and personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:587-599. 32. Kunz M, Sikora J, Krakowski M, Convit A, Cooper TB, Volavka J. Serotonin in violent patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:161-163. 33. Wilson WH, Claussen AM. 18-month outcome of clozapine treatment for 100 patients in a state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:386389. 34. Ratey JJ, Leveroni C, Kilmer D, Gutheil C, Swartz B. The effects of clozapine on severely aggressive psychiatric inpatients in a state hospital. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:219-223. 35. Chiles JA, Davidson P, McBride D. Effects of clozapine on use of seclusion and restraint at a state hospital. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:269-271. 36. Mallya AR, Roos PD, Roebuck-Colgan K. Restraint, seclusion, and clozapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53:395-397. 37. Spivak B, Mester R, Wittenberg N, Maman Z, Weizman A. Reduction of aggressiveness and impulsiveness during clozapine treatment in chronic neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenic patients. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1997;20:442-446. 38. Maier GJ. The impact of clozapine on 25 forensic patients. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1992;20:297-307. 39. Ebrahim GM, Gibler B, Gacono CB, Hayes G. Patient response to clozapine in a forensic psychiatric hospital. Hosp Commun Psychiatry. 1994;45:271-273. 40. Volavka J, Zito JM, Vitrai J, Czobor P. Clozapine effects on hostility and aggression in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1993;13:287-289. 41. Buckley P, Bartell J, Donenwirth MA, et al. Violence and schizophrenia: clozapine as a specific antiaggressive agent. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1995;23:607-611. 42. Citrome L, Volavka J, Czobor P, et al. Effects of clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on hostility in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1510-1514. 43. Czobor P, Volavka J, Meibach RC. Effect of risperidone on hostility in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;15:243-249. 44. Cantillon M, Goldstein JM. Quetiapine fumarate reduces aggression and hostility in patients with schizophrenia. Program and abstracts of American Psychiatric Association 151st Annual Meeting; May 30-June 4, 1998; Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Poster NR444. 45. Citrome L, Krakowski M, Greenberg WM, Andrade E, Volavka J. Antiaggressive effect of quetiapine in a patient with schizoaffective disorder (letter). J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:901. 46. Kinon BJ, Roychowdhury SM, Milton DR, Hill AL. Effective resolution with olanzapine of acute presentation of behavioral agitation and positive psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 2):17-21. 47. Glazer WM, Dickson RA. Clozapine reduces violence and persistent aggression in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 3):8-14. 48. Citrome L, Levine J, Allingham B. Changes in use of valproate and other mood stabilizers for patients with schizophrenia from 1994 to 1998. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:634-638. 49. McEvoy JP, Scheifler PL, Frances A. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series, Treatment of Schizophrenia 1999. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 11):43. 50. Lindenmayer JP, Kotsaftis A. Use of sodium valproate in violent and aggressive behaviors: a critical review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:123128. 51. Hollander E, Margolin L, Wong C, et al. Double-blind placebo trial of divalproex sodium in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Program and abstract of the 38th Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; June 10-13, 1998; Boca Raton, Florida. Poster presentation. 52. Donovan SJ, Stewart JW, Nunes EV, et al. Divalproex treatment for youth with explosive temper and mood lability: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover design. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:818-820. 53. Littrell KH, Petty RG, Hilligoss NM, Peabody CD, Johnson CG. Divalproex sodium for hostility in schizophrenia patients. Program and abstract of the 41st Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; May 28-31, 2001; Phoenix, Arizona. Poster presentation. 54. Casey DE, Daniel D, Tracy K, Wozniak P, Sommerville K. Improved antipsychotic effect of divalproex combined with risperidone or olanzapine for schizophrenia. Program and abstracts of the 26th Biennial Congress of the World Federation for Mental Health; July 23-28, 2001; Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Poster presentation. 55. Collins PJ, Larkin EP, Shubsachs APW. Lithium carbonate in chronic schizophrenia - a brief trial of lithium carbonate added to neuroleptics for treatment of resistant schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:150-154. 56. Shalev A, Hermesh H, Munitz H. Severe akathisia causing neuroleptic failure: An indication for lithium therapy in schizophrenia? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;76:715-718. 57. Simhandl C, Meszaros K. The use of carbamazepine in the treatment of schizophrenic and schizoaffective psychoses: A review. J Psychiatr Neurosci. 1992;17:1-14. 58. Young JL, Hillbrand M. Carbamazepine lowers aggression: a review. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1994;22:53-61. 59. Luchins DJ. Carbamazepine in violent nonepileptic schizophrenics. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1984;20:569-571. 60. Yassa R, Dupont D. Carbamazepine in the treatment of aggressive behavior in schizophrenic patients: a case report. Can J Psychiatry. 1983;28:566-568. 61. Hakola HP, Laulumaa VA. Carbamazepine in treatment of violent schizophrenics (letter). Lancet. 1982;1:1358. 62. Neppe VM. Carbamazepine as adjunctive treatment in nonepileptic chronic inpatients with EEG temporal lobe abnormalities. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44:326-331. 63. Dose M, Apelt S, Emrich HM. Carbamazepine as an adjunct of antipsychotic therapy. Psychiatry Res. 1987;22:303-310. 64. Okuma T, Yamashita I, Takahashi R, et al. A double-blind study of adjunctive carbamazepine versus placebo on excited states of schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;80:250-259. 65. Hesslinger B, Normann C, Langosch JM, Klose P, Berger M, Malden J. Effects of carbamazepine and valproate on haloperidol plasma levels and on psychopathologica outcome in schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:310-315. 66. Yudofsky S, Williams D, Gorman J. Propranolol in the treatment of rage and violent behavior in patients with chronic brain syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1981;138:218-220. 67. Yudofsky SC, Stevens L, Silver JM, Barsa J, Williams D. Propranolol in the treatment of rage and violent behavior associated with Korsakoff's psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:114-115. 68. Volavka J. Can aggressive behavior in humans be modified by beta blockers? (A Special Report). Postgrad Med. 1988:163-168. 69. Sorgi PJ, Ratey JJ, Polakoff S. Beta-adrenergic blockers for the control of aggressive behaviors in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:775-776. 70. Ratey JJ, Sorgi P, O'Driscoll GA, et al. Nadolol to treat aggression and psychiatric symptomatology in chronic psychiatric inpatients: a doubleblind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53:41-46. 71. Alpert M, Allan ER, Citrome L, Laury G, Sison C, Sudilovsky A. A doubleblind, placebo-controlled study of adjunctive nadolol in the management of violent psychiatric patients. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26:367-371. 72. Keats MM, Mukherjee S. Antiaggressive effect of adjunctive clonazepam in schizophrenia associated with seizure disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49:117-118. 73. Karson CN, Weinberger DR, Bigelow L, Wyatt RJ. Clonazepam treatment of chronic schizophrenia: negative results in a double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1627-1628. 74. Goldman MB, Janecek HM. Adjunctive fluoxetine improves global function in chronic schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1990;2:429431. 75. Silver H, Kushnir M. Treatment of aggression in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1298. 76. Vartiainen H, Tiihonen J, Putkonen A, Virkkunen M, Hakola P, Lehto H. Citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, in the treatment of aggression in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;91:348-351. 77. Fink M, Sackeim HA. Convulsive therapy in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bull. 1996;22:27-39. 78. Hirose S, Ashby CR, Mills MJ. Effectiveness of ECT combined with risperidone against aggression in schizophrenia. J ECT. 2001;17:22-26. Authors and Disclosures Authors Leslie Citrome MD, MPH Director, Clinical Research and Evaluation Facility, Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, Orangeburg, New York; Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, New York University, New York City, NY. Disclosure: Leslie Citrome, MD, MPH, has disclosed that he owns stock, has served as an advisor, and has spoken for Lilly. He has served as an advisor or consultant, has received grants, and has spoken for Abbott. He has received grants for clinical research from BMS. He has received grants for clinical research, served as an advisor or consultant, or spoken for Janssen. He has served as an advisor or consultant and spoken for Pfizer. He has served as an advisor or consultant for Novartis. He has spoken for AstraZeneca. This activity discusses off-label uses of psychotropic medications; these medications may not be approved by the FDA for these uses. Clinical Editors Robert Kennedy Psychiatry Site Editor/Program Director, Medscape