SECTION I: A Vulnerable Population

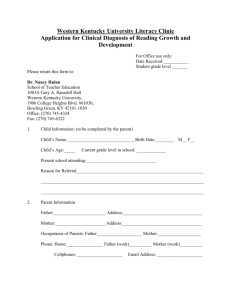

advertisement