torah_sermons148.ser.. - Rabbi Shmuel`s Thoughts on Torah

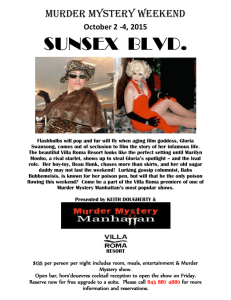

advertisement

Yitro, 5768 Thou Shall Not (be an accessory to) Murder Shmuel Herzeld Which of the Ten Commandments do you think you violate the most? Unfortunately, we all violate many of them far too often. It is almost impossible to never violate the Shabbat—there are so many laws. But that is only once a week…. The commandment to honor the parents is also nearly impossible to get right. The commandment “Do not covet” is another one that is extremely difficult to observe properly. And how many of us can say that we never ever steal, not even a little bit? If there is one commandment where we might assume that we are good about, it is the sixth commandment. “Lo tirtzach, do not murder.” Most of us feel pretty comfortable in the fact that we have never murdered anyone. I am sorry to tell you that we should not feel so comfortable. Here is how the rabbis interpret the sixth commandment: The medieval French commentator, Chezkuni, writes: “Hein beyad, hein be-lashon, hein be-shtikah.” The prohibition of murder can be violated through the hand by physically killing someone, through words, and through silence. Hashem holds us accountable for murder if we cause someone’s death through words and silence. To some extent, this goes beyond American law. Recently there was a case called the, “MySpace Suicide Hoax.” In the MySpace Suicide a 13 year old girl in Missouri committed suicide after she was emotionally manipulated by adult neighbors in her neighborhood. As a “prank” the adults and kids set up a fake boy friend for this girl. They insulted her with words and manipulated her emotions. Some knew about it and kept silent; others actively participated in badgering the self-esteem of a young girl. As Chezkuni argues those who were actively or passively involved in this so-called hoax are considered to have violated the commandment of “lo tirtzach.” We see from this that our words can directly lead to murder. The power of words is overwhelming. Even though this young girl hanged herself, those who insulted her by Jewish law are morally—if not legally—held responsible for murder. In this context we should realize that the commandments are literally called in the Torah, “Aseret Hadevarim”, not the Ten Commandments, but the Ten Utterances. Words have the power to be the holiest sanctification of God’s name and they have the power to destroy. Words or the lack of speaking out can literally lead to murder. Most of us are still feeling pretty good about ourselves. We might think that while we occasionally gossip or insult someone, most of us have not incited a crowd to violence or 1 egged someone on to the point of suicide. But the truth is that the threshold for the violation of this prohibition is even lower. There was once a rabbi named Rabbi Yonah of Gerona who discussed a radical expansion of the prohibition of “lo tirzach.” Rabbenu Yonah was a great Talmudist and a great moralist. But in order to understand who he was, we need to understand his background. In the year 1233, Rabbenu Yonah was one of the leaders of the Maimonidean Controversy. Rabbenu Yonah and other leading rabbis signed a ban against people reading Maimonides’ great philosophical work, The Guide of the Perplexed and the first book of the Mishneh Torah, known as Sefer Ha-Madda. Rabbenu Yonah believed that the philosophical ideas in these works were too dangerous for public. Indeed, he even went further. At his urging the Christian authorities publicly burned Maimomides’ works in Paris in 1233. But once you give people the idea that it is ok to start burning books it is hard to put out the flame and so in 1242, twenty-four wagonloads of the Talmud were burned exactly where Maimonides’ books were burned. When Rabbeinu Yonah saw this he felt that it was divine retribution for his participation in the early burning of Maimonides’ writings and he publicly admitted that he was wrong in front of his entire congregation. For the rest of his life he tried to repent for his activity. He quoted Maimonides frequently and he wrote different works on how to repent. The most famous of these is a masterpiece called Shaarei Teshuvah, the Gates of Repentance, which offers a blueprint to repentance. In this work Shaarei Teshuvah, Rabbeinu Yonah reminds us the Torah commands us to give up our lives rather than violate the big three prohibitions: Idolatry, (Giloi Ariot) Adultery, and Murder. He then discusses a concept called, avizrayhu, or an accessory to those prohibitions and writes that we must give up our lives not only for directly violating those prohibitions but even if we are merely asked to violate an accessory to them. According to Rabbeinu Yonah, thus, we must be killed rather than be an “accessory” to the prohibition of lo tirtzach. (This source was shown to me by Rabbi Josh Hoffman.) Here is what he considers to be an accessory to murder: “Ve-hinei avak-haretzicha halbanat panim ki panav yechevaru ve-nas mareh ha-edom vedomeh al retzichah. The accessory to murder is shaming someone so that his face turns white. His face turns white and its ruddiness disappears and this is like murder.” In Rabbeinu Yonah’s opinion, this is not just a nice moral teaching. This is a legal ruling. He writes that one should allow themselves to be killed rather than embarrass 2 someone to the point where their face turns white. As the Talmud says and he takes literally: “Le-olam yapil atzmo lekivshan ha-eish ve-al yalbin penei chaveiro be-rabim, a person should throw themselves into a fire rather than embarrass someone in public.” Since most of us—myself included—have violated this commandment, there are different ways we can approach such a radical ruling like Rabbeinu Yonah. We can throw up our hands and say it is ridiculous—clearly, embarrassing someone is nowhere nearly as bad as murder. Or, we can ask ourselves if our society is correct in not equating hurting people’s feelings with a physical infliction like murder. Some might suggest that if we seriously equate embarrassing someone with murder then we are devaluing the prohibition of murder. There is that danger. But the alternative—of creating a society that is not sensitive to people’s feelings--is perhaps worse. You can choose to take Rabbeinu Yonah’s teaching literally or you can choose to take it as a nice homily intended to inspire you to be more conscious of people’s feelings. (Maimonides happens to take the latter approach, whereas Tosafot in Sotah agrees with the literal reading of the Talmud of Rabbeinu Yonah.) But what we cannot afford to do is ignore it. The story is told about the great Chofetz Chayim, that a certain person came to purchase all of his scholarly writings. The Chofetz Chayim said to him I noticed that you bought all my books except the ones that talk about lashon hara (gossip). The customer said, “That one is pointless for me as it is too hard for me to keep.” The Chofetz Chayim answered, “It is worth buying the book even if your only reaction at the end reading the book is a sigh.” Here too, it is our responsibility to work on ourselves in these areas of watching our words and refraining from causing people emotional damage even if we sometimes feel that we are hopelessly doomed to keep on sinning. One of the ways we can improve is by studying the laws of interpersonal behavior. The more we have these laws in our mind, the less likely we are to violate them. Everyone should take it upon themselves to study these laws at least once a week—even if the only reaction at the end of the session is a sigh. But really we should demand much more of ourselves. Many of us are in professions where it is taken as the norm that the way to get ahead is by insulting the competition; by putting someone else down; by saying something bad about someone else. This is not the way of Hashem. Think about the example of Rabbeinu Yonah. He was a great rabbi and he was so convinced that he was correct and that Maimonides was wrong. Indeed, he was convinced that Maimonides was spreading heresy and so he criticized Maimonides. But he realized afterwards that his approach was the wrong way to go. If he realized that and 3 in his case he was a great rabbi concerned about a matter as serious as heresy, how much more so as it relates to all of us who are not on his spiritual level and are concerned with matters of lesser significance. In all of our personal lives and in all of our professions we should be pioneers in changing the culture of our society to become a society that does not tolerate “accessories” to murder. 4