[edit] Anti-miscegenation Laws enacted in the Thirteen Colonies and

advertisement

![[edit] Anti-miscegenation Laws enacted in the Thirteen Colonies and](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007722973_2-9341c64e3b85d5d2395ab88368655a6e-768x994.png)

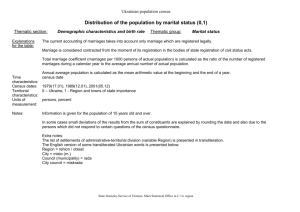

MISCEGENATION LAWS < http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/conlaw/epcscrutiny.htm > Anti-miscegenation laws: From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Anti-miscegenation laws, also known as miscegenation laws, were laws that banned interracial marriage and sometimes sex between members of two different races. In the United States, interracial marriage, cohabitation and sex have since 1863 been termed "miscegenation." Contemporary usage of the term "miscegenation" is less frequent. In North America, laws against interracial marriage and interracial sex existed and were enforced in the Thirteen Colonies from the late seventeenth century onwards, and subsequently in several US states and US territories until 1967. Similar laws were also enforced in Nazi Germany, from 1935 until 1945, and in South Africa during the Apartheid era, from 1948 until 1984.[1] Contents 1 United States o 1.1 Origins in the Colonial Era o 1.2 After American Independence o 1.3 Anti-Miscegenation Laws and the US Constitution 1.3.1 Proposed Anti-Miscegenation Amendments 1.3.2 The repeal of Anti-miscegenation laws, 1948-1967 1.3.2.1 Loving v. Virginia 2 Anti-miscegenation Laws enacted in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States o 2.1 Anti-miscegenation laws repealed before 1887 o 2.2 Anti-miscegenation laws repealed 1948-1967 o 2.3 Anti-miscegenation laws overturned on 12 June 1967 by Loving v. Virginia 3 Asia o 3.1 China o 3.2 British India and Independent India o 3.3 Malaysia 4 Europe o 4.1 Spain o 4.2 France o 4.3 United Kingdom o 4.4 Nazi Germany 5 South Africa under Apartheid 6 See also 7 Notes 8 References 9 External links 2 United States The term miscegenation, a word invented by American journalists to discredit the Abolitionist movement by stirring up debate over the prospect of white-black intermarriage after the abolition of slavery, was first coined in 1863, during the American Civil War.[2] Yet in the Thirteen Colonies laws banning the intermarriage of whites and blacks were enacted as far back as the late seventeenth century.[citation needed] In the United States, anti-miscegenation laws (also known as miscegenation laws) were state laws passed by individual states to prohibit miscegenation, nowadays more commonly referred to as interracial marriage and interracial sex. Typically defining miscegenation as a felony, these laws prohibited the solemnization of weddings between persons of different races and prohibited the officiating of such ceremonies. Sometimes, the individuals attempting to marry would not be held guilty of miscegenation itself, but felony charges of adultery or fornication would be brought against them instead. All anti-miscegenation laws banned the marriage of whites and non-white groups, primarily blacks, but often also Native Americans and Asians.[3] In many states, anti-miscegenation laws also criminalized cohabitation and sex between whites and non-whites. In addition, the state of Oklahoma in 1908 banned marriage "between a person of African descent" and "any person not of African descent", and Kentucky and Louisiana in 1932 banned marriage between Native Americans and African Americans.[4] While anti-miscegenation laws are often regarded as a Southern phenomenon, many northern states had anti-miscegenation laws as well. Although anti-miscegenation amendments were proposed in United States Congress in 1871, 1912-1913 and 1928,[5][6] a nation-wide law against racially mixed marriages was never enacted. From the 19th century into the 1950s, most US states enforced anti-miscegenation laws. From 1913 to 1948, 30 out of the then 48 states did so.[citation needed] In 1967, the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Loving v. Virginia that antimiscegenation laws are unconstitutional. With this ruling, these laws were no longer in effect in the remaining 16 states that at the time still enforced them. [edit] Origins in the Colonial Era The first laws criminalizing marriage and sex between whites and blacks were enacted in the colonial era in the English colonies of Virginia and Maryland, which depended economically on unpaid labor such as indentured servitude and slavery. At first, in the 1660s, the first laws in Virginia and Maryland regulating marriage between whites and blacks only pertained to the marriages of whites with black (and mulatto) slaves and indentured servants. In 1664, Maryland enacted a law which criminalized such marriages. Virginia (1691) was the first English colony in North America to pass a law forbidding free blacks and whites to intermarry, followed by Maryland in 1692. This was the first time in American history that a law was invented that restricted access to marriage partners solely on the basis of "race", not class or condition of servitude.[7] Later these laws also spread to colonies in the Thirteen Colonies with fewer slaves and free blacks, such as Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. Moreover, after the independence of the United States had been established, similar laws were enacted in territories and states which outlawed slavery. A sizable number of the early indentured servants in the British American colonies were brought over from the Indian subcontinent by the East India Company.[citation needed] Anti-miscegenation laws discouraging interracial marriage between white Americans and non-whites affected South Asian immigrants as early as the 17th century.[citation needed] For example, a Eurasian daughter born to an Indian father and Irish mother in Maryland in 1680 was classified as a "mulatto" and sold into slavery .[citation needed] Anti-miscegenation laws there continued into the early 20th century. For example, the Bengali revolutionary Tarak Nath Das's white American wife, Mary K. Das, was stripped of her American citizenship for her marriage to an "alien ineligible for 3 [8] citizenship." In 1918, there was considerable controversy in Arizona when an Indian farmer B. K. Singh married the sixteen year-old daughter of one of his white tenants.[9] In 1724, the French government issued a special Code Noir restricted to Louisiana, which banned the marriage of whites and blacks in that colony.[10] However, interracial cohabitation and interracial sex were never prohibited in French Louisiana (see plaçage). Under Spanish rule, interracial marriage was possible with parental consent under the age of 25 and without it when the partners were older. In 1806, three years after the U.S. gained control over the state, interracial marriage was once again banned.[11] It has been argued that the first laws banning all marriage between whites and blacks, enacted in Virginia and Maryland, were a response by the planter elite to the problems they were facing due to the socio-economic dynamics of the plantation system in the Southern colonies. However, the bans in Virginia and Maryland were established at a time when slavery was not yet fully institutionalized. At the time, most forced laborers on the plantations were indentured servants, and they were mostly white. Some historians have suggested that the atthe-time unprecedented laws banning interracial marriage were originally invented by planters as a divide and rule tactic after the uprising of servants in Bacon's Rebellion. According to this theory, the ban on interracial marriage was issued to split up the racially mixed, increasingly mixed-race labor force into whites, who were given their freedom, and blacks, who were later treated as slaves rather than as indentured servants. By outlawing interracial marriage, it became possible to keep these two new groups separated and prevent a new rebellion. [edit] After American Independence In the 18th, 19th, and early 20th century, many American states passed anti-miscegenation laws, which were often defended by invoking racist interpretations of the Bible, particularly of the story of Phinehas and the "Curse of Ham"[12]. In 1776, seven out of the Thirteen Colonies that declared their independence enforced laws against interracial marriage. Although slavery was gradually abolished in the North after independence, this at first had little impact on the enforcement of anti-miscegenation laws. An exception was Pennsylvania, which repealed its anti-miscegenation law in 1780, together with some of the other restrictions placed on free blacks, when it enacted a bill for the gradual abolition of slavery in the state. Later, in 1843, Massachusetts repealed its anti-miscegenation law after abolitionists protested against it. However, as the US expanded, all the new slave states as well as many new free states such such as Illinois[13] and California[14] enacted such laws. Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Texas, South Carolina and Alabama legalized interracial marriage for some years during the Reconstruction period. Anti-miscegenation laws rested unenforced, were overturned by courts or repealed by the state government (in Arkansas[15] and Louisiana[16]). However, after conservative white Democrats took power in the South during Redemption, anti-miscegenation laws were once more enforced, and in addition Jim Crow laws were enacted in the South which enforced racial segregation.[17] A number of northern and western states permanently repealed their anti-miscegenation laws during the nineteenth century. This, however, did little to halt anti-miscegenation sentiments in the rest of the country. Newly established western states continued to enact laws banning interracial marriage in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Between 1913 and 1948, 30 out of the then 48 states enforced anti-miscegenation laws.[18] Only Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, Vermont, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Alaska, Hawaii, and the federal District of Columbia never enacted them. [edit] Anti-Miscegenation Laws and the US Constitution The constitutionality of anti-miscegenation laws was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1883 case Pace v. Alabama (106 U.S. 583). The Supreme Court ruled that the Alabama anti-miscegenation statute did not 4 violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. According to the court, both races were treated equally, because whites and blacks were punished in equal measure for breaking the law against interracial marriage and interracial sex. This judgment was overturned in 1967 in the Loving v. Virginia case, where the Supreme Court declared anti-miscegenation laws a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and therefore unconstitutional. [edit] Proposed Anti-Miscegenation Amendments At least three proposed constitutional amendments intended to bar interracial marriage in the United States have been introduced in Congress.[19] In 1871, Representative Andrew King (Democrat of Missouri) was the first politician in Congress to propose a constitutional amendment to make interracial marriage illegal nation-wide. King proposed this amendment because he feared that the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868 to give equal civil rights to the emancipated ex-slaves (the Freedmen) as part of the process of Reconstruction, would render laws against interracial marriage unconstitutional. In December 1912 and January 1913, Representative Seaborn Roddenbery (Democrat of Georgia) again introduced a proposal in the United States House of Representatives to insert a prohibition of miscegenation into the US Constitution and thus create a nation-wide ban on interracial marriage. According to the wording of the proposed amendment, "Intermarriage between negros or persons of color and Caucasians... within the United States... is forever prohibited." Roddenbery's proposal was more severe because it defined the racial boundary between whites and "persons of color" by applying the one-drop rule. In his proposed amendment, anyone with "any trace of African or Negro blood" was banned from marrying a white spouse. Roddenbery's proposed amendment was also a direct reaction to African American heavyweight champion Jack Johnson's marriages to white women, first to Etta Duryea and then to Lucille Cameron. In 1908, Johnson had become the first black boxing world champion, having beaten Tommy Burns. After his victory, the search was on for a white boxer, a "Great White Hope", to beat Johnson. Those hopes were dashed in 1912, when Johnson beat former world champion Jim Jeffries. This victory ignited race riots all over America as frustrated whites attacked celebrating African Americans [Rust and Rust, 1985, p. 147]. Johnson's marriages to and affairs with white women further infuriated white Americans. In his speech introducing his bill before the United States Congress, Roddenbery compared the marriage of Johnson and Cameron to the enslavement of white women, and warned of future civil war that would ensue if interracial marriage was not made illegal nationwide: "No brutality, no infamy, no degradation in all the years of southern slavery, possessed such villainious character and such atrocious qualities as the provision of the laws of Illinois, Massachusetts, and other states which allow the marriage of the negro, Jack Johnson, to a woman of Caucasian strain. [applause]. Gentleman, I offer this resolution ... that the States of the Union may have an opportunity to ratifty it. ... Intermarriage between whites and blacks is repulsive and averse to every sentiment of pure American spirit. It is abhorrent and repugnant to the very principles of Saxon government. It is subversive of social peace. It is destructive of moral supremacy, and ultimately this slavery of white women to black beasts will bring this nation a conflict as fatal as ever reddened the soil of Virginia or crimsoned the mountain paths of Pennsylvania. ... Let us uproot and exterminate now this debasing, ultra-demoralizing, un-American and inhuman leprosy" Congressional Record, 62d. Congr., 3d. Sess., December 11, 1912, pp. 502–503. Spurred on by Roddenbery's introduction of the anti-miscegenation amendment, politicians in many of the 19 states lacking anti-miscegenation laws proposed their enactment. However, Wyoming in 1913 was the only state lacking such a law that enacted one.[citation needed] Also in 1913, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which 5 [20] had abolished its anti-miscegenation law in 1843, enacted a measure (not repealed until 2008 ) that prevented couples who could not marry in their home state from marrying in Massachusetts.[21] In 1928, Representative Coleman Blease (Democrat of South Carolina) proposed an amendment that went beyond the previous ones, requiring that Congress set a punishment for interracial couples attempting to get married and for people officiating an interracial marriage. This amendment was also never enacted.[22] [edit] The repeal of Anti-miscegenation laws, 1948-1967 The constitutionality of anti-miscegenation laws only began to be widely called into question after the World War II. In 1948, the California Supreme Court in Perez v. Sharp ruled that the Californian anti-miscegenation statute violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution and was therefore unconstitutional. This was the first time since Reconstruction that a state court had declared an anti-miscegenation law unconstitutional. California was the first state since Ohio in 1887 to repeal its anti-miscegenation law. As a result, during the 1950s, anti-miscegenation laws were repealed or overturned in state after state, except in the South. Nonetheless, in the 1950s, the repeal of anti-miscegenation laws was still a controversial issue in the U.S., even among supporters of racial integration. In 1958, the political theorist Hannah Arendt, an emigre from Nazi Germany, wrote in an essay in response to the Little Rock Crisis, the Civil Rights struggle for the racial integration of public schools which took place in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957, that anti-miscegenation laws were an even deeper injustice than the racial segregation of public schools. The free choice of a spouse, she argued in Reflections on Little Rock, was "an elementary human right": "Even political rights, like the right to vote, and nearly all other rights enumerated in the Constitution, are secondary to the inalienable human rights to 'life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness' proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence; and to this category the right to home and marriage unquestionably belongs." Arendt was severely criticized by fellow liberals, who feared that her essay would arouse the racist fears common among whites and thus hinder the struggle of African-Americans for Civil Rights and racial integration. Commenting on the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka against de jure racial segregation in education, Arendt argued that anti-miscegenation laws were more basic to racial segregation than racial segregation in education. Arendt's analysis of the centrality of laws against interracial marriage to white supremacy echoed the conclusions of Gunnar Myrdal. In his essay, Social Trends in America and Strategic Approaches to the Negro Problem (1948), Myrdal ranked the social areas where restrictions were imposed by Southern whites on the freedom of African-Americans through racial segregation from the least to the most important: jobs, courts and police, politics, basic public facilities, "social equality" including dancing and handshaking, and most importantly, marriage. This ranking was indeed reflective of the way in which the barriers against desegregation fell under the pressure of the protests of the emerging Civil Rights movement. First, legal segregation in the army, in education and in basic public services fell, then restrictions on the voting rights of African-Americans were lifted. These victories were ensured by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But the bans on interracial marriage were the last to go, in 1967. Most white Americans in the 1950s were opposed to interracial marriage and did not see laws banning interracial marriage as an affront to the principles of American democracy. A 1958 Gallup poll showed that 96 percent of white Americans disapproved of interracial marriage. However, attitudes towards bans on interracial marriage quickly changed in the 1960s. By the 1960s, civil rights organizations were helping interracial couples who were being penalized for their relationships to take their cases to the Supreme Court. Since Pace v. Alabama, the court had declined to make a judgment in such cases. But in 1964, the Warren Court decided to issue a ruling in the case of an interracial 6 couple from Florida who had been convicted because they had cohabited. In McLaughlin v. Florida, the Supreme Court ruled that the Florida state law which prohibited cohabitation between whites and non-whites was unconstitutional and based solely on a policy of racial discrimination. However, the court did not rule on the Florida's ban on marriage between whites and non-whites, despite the appeal of the plaintiffs to do so and the argument made by the state of Florida that its ban on cohabitation between whites and blacks was ancillary to its ban on marriage between whites and blacks. However, in 1967, the court did decide to rule on the remaining anti-miscegenation laws when it was presented with the case of Loving v. Virginia. [edit] Loving v. Virginia Main article: Loving v. Virginia All bans on interracial marriage were lifted only after an interracial couple from Virginia, Richard and Mildred Loving, began a legal battle in 1963 for the repeal of the anti-miscegenation law which prevented them from living as a couple in their home state of Virginia. The Lovings were supported by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the Japanese American Citizens League and a coalition of Catholic bishops. In 1958, Richard and Mildred Loving had married in Washington, D.C. to evade Virginia's anti-miscegenation law (the Racial Integrity Act). Having returned to Virginia, they were arrested in their bedroom for living together as an interracial couple. The judge suspended their sentence on the condition that the Lovings would leave Virginia and not return for 25 years. In 1963, the Lovings, who had moved to Washington, D.C, decided to appeal this judgment. In 1965, Virginia trial court Judge Leon Bazile, who heard their original case, refused to reconsider his decision. Instead, he defended racial segregation, writing: "Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix."[23] The Lovings then took their case to the Supreme Court of Virginia, which invalidated the original sentence but upheld the state's Racial Integrity Act. Finally, the Lovings turned to the U.S Supreme Court. The court, which had previously avoided taking miscegenation cases, agreed to hear an appeal. In 1967, 84 years after Pace v. Alabama in 1883, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Loving v. Virginia that: "Marriage is one of the 'basic civil rights of man,' fundamental to our very existence and survival.... To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discriminations. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not to marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State." The Supreme Court condemned Virginia's anti-miscegenation law as "designed to maintain White supremacy". In 1967, 17 Southern states (all the former slave states plus Oklahoma) still enforced laws prohibiting marriage between whites and people of color. Maryland repealed its law in response to the start of the proceedings at the Supreme Court. After the ruling of the Supreme Court, the remaining laws were no longer in effect. Nonetheless, it took South Carolina until 1998 and Alabama until 2000 to officially amend their states' constitutions to remove language prohibiting miscegenation. In the respective referendums, 62% of voters in South Carolina and 59% of voters in Alabama voted to remove these laws.[24] 7 In 2009, Keith Bardwell, a justice of the peace in Robert, Louisiana, refused to officiate a civil wedding for an interracial couple. A nearby justice of the peace, on Bardwell's referral, officiated the wedding; the interracial couple sued Keith Bardwell and his wife Beth Bardwell in federal court.[25] See refusal of interracial marriage in Louisiana. [edit] Anti-miscegenation Laws enacted in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States U.S States, by the date of repeal of anti-miscegenation laws: No laws passed Before 1887 1948 to 1967 12 June 1967 [edit] Anti-miscegenation laws repealed before 1887 First law passed Illinois 1829 Iowa 1839 Kansas 1855 New Mexico 1857 Law repealed 1874 1851 1859 1866 Maine 1821 1883 Massachusetts 1705 1843 Michigan 1838 1883 Ohio 1861 1887 Pennsylvania 1725 Rhode Island 1798 1780 1881 State Races banned from Note marrying whites Blacks Blacks Blacks Law repealed before reaching statehood Blacks Law repealed before reaching statehood Blacks, Native Americans Passed the 1913 law preventing out-of-state Blacks, Native couples from circumventing their home-state antiAmericans miscegenation laws Blacks Last state to repeal its anti-miscegenation law Blacks before California did so in 1948 Blacks Blacks, Native 8 Washington 1855 1868 Americans Blacks, Native Americans Law repealed before reaching statehood [edit] Anti-miscegenation laws repealed 1948-1967 State Arizona First law Law passed repealed 1865 1962 California 1850 1948 Colorado 1864 1957 Idaho 1864 1959 Indiana 1818 1965 Maryland 1692 1967 Montana 1909 Nebraska 1855 1953 1963 Nevada 1861 1959 North Dakota 1909 1955 Oregon 1862 1951 South Dakota 1909 1957 Utah 1852 1963 Wyoming 1913 1965 Races banned from Note marrying whites Blacks, Asians, Filipinos ("Malays") and Indians ("Hindus") added to Filipinos, Indians list of "races" in 1931 Anti-miscegenation law overturned by state judiciary Blacks, Asians, in Supreme Court of California case Perez v. Sharp. Filipinos Most Hispanics were included in White category. Blacks Blacks, Native Americans, Asians Blacks Repealed its law in response to the start of the Loving Blacks, Filipinos v. Virginia case Blacks, Asians Blacks, Asians Blacks, Native Americans, Asians, Filipinos Blacks Blacks, Native Americans, Asians, Native Hawaiians Blacks, Asians, Filipinos Blacks, Asians, Filipinos Blacks, Asians, Filipinos [edit] Anti-miscegenation laws overturned on 12 June 1967 by Loving v. Virginia State Alabama Arkansas Delaware Florida Georgia First law passed 1822 1838 1721 1832 1750 Races banned from marrying whites Blacks Blacks Blacks Blacks All non-whites Note Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated 9 Kentucky Louisiana Mississippi Missouri North Carolina Oklahoma South Carolina Tennessee Texas 1792 1724 1822 1835 Blacks Blacks Blacks, Asians Blacks, Asians 1715 Blacks, Native Americans 1897 Blacks 1717 All non-whites 1741 1837 Blacks, Native Americans Blacks, Filipinos Virginia 1691 All non-whites West Virginia 1863 Blacks Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated Previous anti-miscegenation law made more severe by Racial Integrity Act of 1924 [edit] Asia [edit] China There have been various periods in the history of China where large numbers of Arabs, Persians and Turks from the "Western Regions" (Central Asia and West Asia) migrated to China, beginning with the arrival of Islam during the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century. Due to the majority of these immigrants being male, they often intermarried with local Han Chinese females. There were laws and policies which discouraged miscegenation during the Tang Dynasty, 836 AD, a decree forbidding Chinese to have relations with peoples of color, such as Iranians, Arabs, Indians, Malays, Sumatrans, and so on.[26] Race riots and massacres resulting in the deaths of several thousand Muslim merchants like Arabs and Persians in Hangzhou occurred. These laws were later relaxed during the Song Dynasty, which allowed third-generation immigrants with official titles to intermarry with Chinese imperial princesses. Immigration to China increased under the Mongol Empire, when large numbers of West and Central Asians were brought over to help govern Yuan China in the 13th century. Intermarriage was later encouraged during the Ming Dynasty.[27] During the Qing dynasty, Manchus and Mongols were prohibited from marrying the Han Chinese but those within the Eight Banners were exempt, usually a Manchu bannerman to a Han bannerwoman.[28] In 1822, all Manchu men were given the right to marry Han women. The edict prohibiting miscegenation was thoroughly repealed on February 1, 1902. [edit] British India and Independent India As British females began arriving to British India in large numbers around the early to mid-19th century, miscegenation became increasingly common. Relations between Indian men and British women became despised after the events of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, known as "India's First War of Independence" to the Indians and as the "Sepoy Mutiny" to the British, where Indian sepoys rebelled against the British East India Company. While incidents of war rape committed by Indian rebels against English women and girls occurred during the rebellion, this was exaggerated to great effect by the British media in order to justify vicious reprisals in the short run and continued British colonialism in the Indian subcontinent in the long run.[29] 10 Despite the questionable authenticity of many colonial accounts regarding the rebellion, the stereotype of the Indian "dark-skinned rapist" occurred frequently in English literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The idea of protecting English "female chastity" from the "lustful Indian male" had a significant influence on the policies of the British Raj. However, while widespread prejudice, and the fear of professional and personal ruin prevented significant numbers from inter-marrying, there were no formal laws prohibiting marriage between Britons and Indians in British-ruled India.[citation needed] India's Constitution refers to the children of an Indian father and European mother as Indian but the children of a European father and Indian mother as "Anglo-Indian".[30] [edit] Malaysia In Malaysia, the majority of inter-ethnic marriages are between Chinese and Indians. The offspring of such marriages are informally known as "Chindian", though the Malaysian government only classifies them by their father's ethnicity. As the majority of these intermarriages usually involve an Indian groom and Chinese bride, the majority of Chindians in Malaysia are usually classified as "Indian" by the Malaysian government. Certain religion-based anti-miscegenation laws apply to the Malays, however, who are predominantly Muslim. Legal restrictions in Malaysia make it very difficult for Malays to intermarry with either the Chinese or Indian populations.[31] [edit] Europe [edit] Spain After the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in the 8th century, the Islamic state of Al-Andalus was established in the Iberian Peninsula, where it was common for Arab and Berber males from North Africa to intermarry with the local Visigothic, Suebi, Roman and Iberian females of Hispania.[32][33] The offspring of such marriages were known as Muladi or Muwallad, an Arabic term still used in the modern Arab world to refer to people with an Arab parent and a non-Arab parent.[34] This term was also the origin for the Spanish word Mulatto.[35][36] By the 11th or 12th century, the Muslim population of Al-Andalus had merged into a homogeneous group of people known as the "Moors". After the Reconquista, which was completed in 1492, most of the Moors were forced to either flee to Morocco or convert to Christianity. The ones who converted to Christianity were known as Moriscoes, and they were often targeted by the Spanish Inquisition as suspects of heresy on the basis of the Limpieza de sangre ("Cleanliness of blood") or "blue blood" doctrine, under which anti-miscegenation laws were implemented in Spain, which prevented miscegenation between those with pure European blood and those with Moorish or Jewish blood.[37][dubious – discuss] Anyone whose ancestors had miscegenated with the Moors or Jews were also especially monitored by the Inquisition to prevent their return to the Islamic or Jewish faiths. [edit] France During World War I, there were 135,000 soldiers from British India,[38] a large number of soldiers from French North Africa,[39] and 20,000 labourers from South Africa,[40] who served in France. Much of the French male population had gone to war, leaving behind a surplus of French females,[41] many of whom formed interracial relationships with non-white soldiers, mainly Indian[42][43] and North African.[38] British and French authorities allowed foreign Muslim soldiers to intermarry with local French females on the basis of Islamic law, which allows marriage between Muslim males and Christian and Jewish females. On the other hand, Hindu soldiers in France were restricted from intermarriage on the basis of the Indian caste system.[43] 11 While the French were not as concerned about interracial relationships, the British made attempts to prevent their Indian troops from engaging in such relationships with white females, by implementing curfews and preventing female nurses from servicing wounded Indian troops in British-run hospitals.[39] On the other hand, French-run hospitals had no problem with having female nurses servicing wounded Indian and North African soldiers, though contacts with black African labourers and soldiers were more severely restricted by both British and French authorities.[38][44] [edit] United Kingdom Following World War I, there was a large surplus of females in the United Kingdom,[45] and there were increasing numbers of seamen arriving from the Indian subcontinent, Arab World, Far East and Caribbean. This led to increased intermarriage and cohabitation with local white females, which raised concerns over miscegenation and led to several race riots at the time.[46] In the 1920s to 1940s, several legal scholars raised concerns about an increasing 'mixed-breed' population, born mainly from foreign Muslim (mostly Indian as well as Arab, Malayan and Somali) fathers and local white mothers, occasionally out of wedlock. They denounced white girls who mixed with foreign Muslim men as 'shameless' and called for a legislative ban on the breeding of 'half-caste' children. These calls for anti-miscegenation laws were unsuccessful, however.[47] [edit] Nazi Germany Discrimination against miscegenation mostly followed the mainstream Nazi anti-Semitism, which considered the Jewry as being a group of people bound by close, so-called genetic (blood) ties, to form a unit, which one could not join or secede from. The influence of Jews had been declared to have detrimental impact on Germany, in order to rectify the discriminations and persecutions of Jews. To be spared from that, one had to prove one's affiliation with the group of the so-called Aryan race. Although Nazi doctrine stressed the importance of physiognomy and genes in determining race, in practice race was determined only through the religions followed by each individual's ancestors. Individuals were considered "non-Aryan" (ie. Jewish) if at least three of four of their grandparents had been enrolled as members of a Jewish congregation; it did not matter if those grandparents had been born to a Jewish family or had converted to Judaism in adulthood. The actual religious beliefs of the individual himself or herself were also immaterial, as was the individual's status under Halachic law. An anti-miscegenation law was enacted by the National Socialist government in September 1935 as part of the Nuremberg Laws. The Gesetz zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre (Protection of German Blood and German Honor Act), enacted on 15 September 1935, forbade marriage and extramarital sexual relations between persons racially – or rather racistically – regarded as so-called non-Aryans and Aryans (persons of “German or related blood”), this included all marriages, where at least one partner was a German citizen.[48] Non-Aryans comprised mostly Jewish Germans and Gentile Germans of Jewish descent. However, Germans of extra-European and especially of African descent and Germans regarded as belonging to the minority group of Sinti and Roma (Gypsies) were also considered as non-Aryans. On November 14, the law was extended to Gypsies and Blacks[49]. Such extramarital intercourse was marked as Rassenschande (lit. racedisgrace) and could be punished by imprisonment - later usually followed by the deportation to a concentration camp, often entailing the inmate's death. Germans of African and other extra-European descent were classified following their own origin or the origin of their parents. Sinti and Roma were mostly categorised following police records, e.g. mentioning them or their forefathers as Gypsies, when having been met by the police as travelling peddlers. The existing 20,454 (as of 1939) marriages between persons racially regarded as so-called Aryans and so-called non-Aryans - called mixed marriages (German: Mischehe) - would continue.[50] However, the government eased 12 [51] the conditions for the divorce of mixed marriages. In the beginning the Nazi authorities hoped to make the so-called Aryan partner get a divorce from their non-Aryan-classified spouses, by granting easy legal divorce procedures and opportunities for the so-called Aryan spouse to withhold most of the common property after a divorce.[52] Those who stuck to their spouse, would suffer discriminations like dismissal from public employment, exclusion from civic society organisations, etc.[53] Eventual children - whenever born - within a mixed marriage, as well as children from extramarital mixed relationships born until July 31, 1936, were discriminated as Mischlinge. However, children later born to mixed parents, not yet married at passing the Nuremberg Laws, were to be discriminated as Geltungsjuden, regardless if the parents had meanwhile married abroad or remained unmarried. Eventual children, who were enrolled in a Jewish congregation, were also subject to the discrimination as Geltungsjuden. According to the Nazi family value attitude the husband was regarded the head of a family. Thus people living in a so-called mixed marriage were treated differently according to the sex of the so-called Aryan spouse and according to the religious affiliation of the children, their being or not being enrolled with a Jewish congregation. Nazi-termed mixed marriages were often not interfaith marriages, because in many cases the classification of one spouse as non-Aryan was only due to her or his grandparents, being enrolled with a Jewish congregation or else classified as non-Aryan. In many cases both spouses had a common faith, either because the parents had already converted or because at marrying one spouse converted to the religion of the second (Marital conversion). Traditionally the wife used to be the convert.[54] However, in urban areas and after 1900 actual interfaith marriages occurred more often, with interfaith marriages legally allowed in some states of the German Confederation since 1847, and generally since 1875, when civil marriage became an obligatory prerequisite for any religious marriage ceremony all around united Germany. Most mixed marriages occurred with one spouse being considered as non-Aryan, due to his or her Jewish descent. So many special regulations were developed for such couples. A differentiation of privileged and other mixed marriages emerged on 28 December 1938, when Hermann Göring discretionarily ordered this in a letter to the Reich's Ministry of the Interior.[55] The "Gesetz über die Mietverhältnisse mit Juden" (English: Law on Tenancies with Jews) of 30 April 1939, allowing proprietors to unconditionally cancel tenancy contracts with Germans, classified as Jews, and forcing them to move into houses reserved for them, for the first time enacted Göring's spontaneous creation, by defining so-called privileged mixed marriages and excepting them from the act.[56] The legal definitions decreed: The marriage of a Gentile husband and his wife, being a Jewess or being classified as a Jewess due to her descent, was generally considered to be a so-called privileged mixed marriage, unless they had children, who were enrolled in a Jewish congregation. Then the husband was obviously not the dominant part in the family and the wife had to wear the Yellow badge and the children as well, who were thus discriminated as Geltungsjuden. Without children, or with children not enrolled with a Jewish congregation, the Jewish-classified wife was spared from wearing the yellow badge (else compulsory for Germans classified as Jews as of 1 September 1941). In the opposite case, when the wife was classified as an Aryan and the husband as a Jew, the husband had to wear the yellow badge, if they had no children or children enrolled with a Jewish congregation. In case they had common children not enrolled in a Jewish congregation (irreligionist, Christian etc.) they were discriminated as Mischlinge and their father was spared from wearing the yellow badge. Since there was no elaborate regulation, the practice of excepting privileged mixed marriages from anti-Semitic invidiousnesses varied amongst Greater Germany's different Reichsgaue, however all discriminations enacted until December 28, 1938 remained valid without exceptions for privileged mixed marriages. In the Reichsgau Hamburg, e.g., Jewish-classified spouses living in privileged mixed marriages received equal food rations like Aryan-classified Germans, in many other Reichsgaue they received shortened rations.[57] In some Reichsgaue 13 also privileged mixed couples and their eventually minor children, whose father was classified as a Jew, were forced to move into houses reserved for Jews only, in 1942 and 1943, thus making a privileged mixed marriage one, where the husband was the one classified Aryan. The arbitrary practice for privileged mixed marriages led to different compulsions to forced labour in 1940, partially ordered for all Jewish-classified spouses, or only for Jewish-classified husbands or only excepting Jewish-classified wives, taking care of minor children. No document indicated the exception of a mixed marriage from some persecutions and especially of its Jewish-classified spouse.[58] Thus on an eventual arrest, non-arrested relatives or friends had to prove the exceptional status, hopefully fast enough to rescue the arrested from eventual deportation or else what. Systematic deportations of Jewish Germans and Gentile Germans of Jewish descent started on October 18, 1941.[59] German Jews and Jewesses and German Gentiles of Jewish descent living in mixed marriage were in fact mostly spared from deportation.[60] In case a mixed marriage ended by death of the so-called Aryan spouse or divorce the Jewish-classified spouse, residing within Germany, was usually deported soon after, unless the couple still had minor children not counting as Geltungsjuden.[57] In March 1943 an attempt to deport the Berlin-based Jews and Gentiles of Jewish descent, living in nonprivileged mixed marriages, failed due to public protest by their relatives-in-law of so-called Aryan kinship (see Rosenstraße protest). Also the Aryan-classified husbands and Mischling-classified children (starting at the age of 16) from mixed marriages were taken by the Organisation Todt for forced labour, starting in autumn 1944. A last attempt, undertaken in February/March 1945 ended, because the extermination camps already were liberated. However, 2,600 from all over the Reich were deported to Theresienstadt, of whom most survived the last months until their liberation.[61] With the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945 the laws banning so-called mixed marriages were lifted again. If couples, who lived together already during the Nazi era, however unmarried due to the legal restrictions, married after the war, their date of marriage had been legally retroactively backdated, if they wished so, to the date they formed a couple.[62] Even if one spouse was already dead, the marriage could be retroactively recognised, in order to legitimise eventual children and enable them or the surviving spouse to inherit from their late father or partner, respectively. In the West German Federal Republic of Germany 1,823 couples applied for recognition, which was granted in 1,255 cases. [edit] South Africa under Apartheid South Africa’s Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, passed in 1949 under Apartheid, forbade marriages between whites and non-whites. The Population Registration Act (No. 30) of 1950 provided the basis for separating the population of South Africa into different races. Under the terms of this act, all residents of South Africa were to be classified as white, coloured, or native (later called Bantu) people. Indians were included under the category "Asian" in 1959. Also in 1950, the Immorality Act was passed, which criminalized all sexual relations between whites and non-whites. The Immorality Act of 1950 extended an earlier ban on sexual relations between whites and blacks (the Immorality Act [No. 5] of 1927) to a ban on sexual relations between whites and any non-whites.[63] Both Acts were repealed in 1985. [edit] See also 1913 law Amalgamation (history) Apartheid 14 Hypodescent Interracial marriage Jim Crow laws Judicial aspects of race in the United States Loving Day Loving v. Virginia McLaughlin v. Florida Miscegenation Nuremberg laws One drop rule Pace v. Alabama Perez v. Sharp Race (historical definitions) Racial Integrity Act of 1924 Scientific racism Social interpretations of race [edit] Notes 1. ^ David Hollinger (2003) Amalgamation and Hypodescent: The Question of Ethnoracial Mixture in the History of the United States, American Historical Review, Vol. 108, Iss. 5 2. ^ Fredrickson, George M. (1987), The Black Image in the White Mind, Wesleyan University Press, p. 172, ISBN 0819561886, http://books.google.com/books?id=MB8Zmmm7L-wC 3. ^ Chin, Gabriel J. & Hrishi Karthikeyan, Preserving Racial Identity: Population Patterns and the Application of Anti-Miscegenation Statutes to Asian Americans, 1910-1950, 9 Asian Law Journal 1 (2002) 4. ^ The History of Jim Crow 5. ^ Courtroom History, Loving Day, http://lovingday.org/courtroom.htm, retrieved 2008-01-02 6. ^ Edward Stein (2004) (pdf), PAST AND PRESENT PROPOSED AMENDMENTS TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION REGARDING MARRIAGE∗, 82, Washing State University Law Quarterly, http://web.archive.org/web/20060812025324/http://law.wustl.edu/WULQ/823/p+611+Stein+book+pages.pdf, retrieved 2008-01-04, archived from the original on 2006-08-12. 7. ^ Frank W Sweet (January 1, 2005), The Invention of the Color Line: 1691—Essays on the Color Line and the One-Drop Rule, Backentyme Essays, http://www.backintyme.com/essay050101.htm, retrieved 2008-01-04 8. ^ Francis C. Assisi (2005), Indian-American Scholar Susan Koshy Probes Interracial Sex, INDOlink, http://www.indolink.com/displayArticleS.php?id=111605054006, retrieved 2009-01-02 9. ^ Echoes of Freedom: South Asian Pioneers in California, 1899-1965 - Chapter 9: Home Life, The Library, University of California, Berkeley, http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/SSEAL/echoes/chapter9/chapter9.html, retrieved 2009-01-08 10. ^ Interracial Marriage and Cohabitation Laws, Redbone Heritage Foundation, http://www.redboneheritagefoundation.com/Chronicles/interracial_marriage_timeline.htm, retrieved 2008-01-04 11. ^ Kimberly S. Hanger, Bounded Lives, Bounded Places: Free Black Society in Colonial New Orleans,1769-1803. Durham N.C., and London: Duke University Press, 1997. 12. ^ Stephen R. Haynes (2002), Noah's Curse: The Biblical Justification of American Slavery, Oxford University Press US, http://books.google.com/books?id=ioYDJ4GK3tYC, retrieved 2008-01-07 13. ^ Steiner, Mark. “The Lawyer as Peacemaker: Law and Community in Abraham Lincoln’s Slander Cases”. The History Cooperative 15 14. ^ enacted similar anti-miscegenation laws.“Chinese Laborers in the West”Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program 15. ^ Robinson II, Charles F., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. (accessed January 4, 2007). 16. ^ Miscegenation and competing definitions of race in twentieth-century Louisiana. 17. ^ Wallenstein, Peter, Tell the Court I love my wife 18. ^ Where were interracial couples illegal?, Loving Day, http://lovingday.org/map.htm, retrieved 200801-04 19. ^ John R. Vile (2003), Encyclopedia of constitutional amendments, proposed amendments, and amending issues, 1789-2002 (second ed.), ABC-CLIO, p. 243, ISBN 9781851094288, http://books.google.com.ph/books?id=T0IGUhxqUuYC 20. ^ "Governor signs law allowing out-of-state gays to wed". The Boston Globe. 2008-07-31. http://www.boston.com/news/local/breaking_news/2008/07/gov_to_sign_bil.html?p1=Well_MostPop_E mailed7. Retrieved 2009-09-11. 21. ^ "Big marriage rulings are coming in the next month". Gay People's Chronicle. 2006-02-17. http://www.gaypeopleschronicle.com/stories06/february/0217063.htm. Retrieved 2009-09-11. 22. ^ Anti-Miscagenation laws, Reference.com, http://www.reference.com/browse/wiki/Antimiscegenation_laws 23. ^ Tucker, Neely (June 13, 2006). “Loving Day Recalls a Time When the Union of a Man And a Woman Was Banned”. Washington Post. 24. ^ Alabama removes ban on interracial marriage, USA Today, November 7, 2000, http://www.usatoday.com/news/vote2000/al/main03.htm, retrieved 2008-01-04 25. ^ Eileen Sullivan and the Associated Press, "Man's halt of interracial marriage sparks outrage" in New York Times, October 16, 2009; Humphrey v. Bardwell on Justia. 26. ^ Gernet, Jacques (1996), A History of Chinese Civilization (2 ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 294, http://books.google.com/books?id=jqb7L-pKCV8C, ISBN 0521497817, ISBN 9780521497817. 27. ^ Chinese of Arab and Persian descent, ColorQ World, http://www.colorq.org/MeltingPot/article.aspx?d=Asia&x=ChineseWestAsians, retrieved 2008-12-23 28. ^ Ebrey, Patricia (1993). Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook. Simon and Schuster, 29. ^ Beckman, Karen Redrobe (2003), Vanishing Women: Magic, Film, and Feminism, Duke University Press, pp. 31–3, ISBN 0822330741 30. ^ Constitution of India in English, Part XIX., Art.366(2): " 'an Anglo-Indian' means a person whose father or any of whose other male progenitors in the male line is or was of European descent but who is domiciled within the territory of India and is or was born within such territory of parents habitually resident therein and not established there for temporary purposes only;". 31. ^ Daniels, Timothy P. (2005), Building Cultural Nationalism in Malaysia, Routledge, p. 189, ISBN 0415949718 32. ^ Thomas F. Glick, Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages 33. ^ Ivan van Sertima (1992), Golden Age of the Moor, Transaction Publishers, ISBN 1560005815 34. ^ Kees Versteegh, et al. Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, BRILL, 2006. 35. ^ Izquierdo Labrado, Julio (in Spanish), La esclavitud en Huelva y Palos (1570-1587), http://www.mgar.net/var/esclavos3.htm, retrieved 2008-07-14 36. ^ Salloum, Habeeb, The impact of the Arabic language and culture on English and other European languages, The Honorary Consulate of Syria, http://www.syriatoday.ca/salloum-arab-lan.htm, retrieved 2008-07-14 37. ^ Robert Lacey (1983), Aristocrats, p. 67, Little, Brown and Company 38. ^ a b c Enloe, Cynthia H. (2000), Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women's Lives, University of California Press, p. 61, ISBN 0520220714 39. ^ a b Greenhut, Jeffrey (April 1981), "Race, Sex, and War: The Impact of Race and Sex on Morale and Health Services for the Indian Corps on the Western Front, 1914", Military Affairs (Society for Military History) 45 (2): 71–74, doi:10.2307/1986964 16 40. ^ Levine, Philippa (1998), "Battle Colors: Race, Sex, and Colonial Soldiery in World War I", Journal of Women's History 9 41. ^ Greenhut, Jeffrey (April 1981), "Race, Sex, and War: The Impact of Race and Sex on Morale and Health Services for the Indian Corps on the Western Front, 1914", Military Affairs (Society for Military History) 45 (2): 71–74 [72–4], doi:10.2307/1986964 42. ^ Dowling, Timothy C. (2006), Personal Perspectives: World War I, ABC-CLIO, pp. 35–6, ISBN 1851095659 43. ^ a b Omissi, David (2007), "Europe Through Indian Eyes: Indian Soldiers Encounter England and France, 1914–1918", English Historical Review (Oxford University Press) CXXII (496): 371–96, doi:10.1093/ehr/cem004 44. ^ Bland, Lucy (April 2005), "White Women and Men of Colour: Miscegenation Fears in Britain after the Great War", Gender & History 17 (1): 29–61 [34–5], doi:10.1111/j.0953-5233.2005.00371.x 45. ^ Ansari, Humayun (2004), The Infidel Within: The History of Muslims in Britain, 1800 to the Present, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, p. 94, ISBN 1850656851 46. ^ Bland, Lucy (April 2005), "White Women and Men of Colour: Miscegenation Fears in Britain after the Great War", Gender & History 17 (1): 29–61, doi:10.1111/j.0953-5233.2005.00371.x 47. ^ Ansari, Humayun (2004), The Infidel Within: The History of Muslims in Britain, 1800 to the Present, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, pp. 93–4, ISBN 1850656851 48. ^ The existence of an Aryan race and other non-Aryan races as conceived and categorised by Nazism was an arbitrary and unscientific figment of Nazi racism. 49. ^ US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Nuremberg Laws: Nazi Racial Policy 1935, http://www.ushmm.org/outreach/nlawchr.htm 50. ^ Beate Meyer, Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der Hamburger Juden 1933-1945, Landeszentrale für politische Bildung (ed.), Hamburg: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2006, p. 80. ISBN 3-92972885-0 51. ^ Before 1933 the term Mischehe referred to interfaith marriages, which was a tax office phenomenon. German tax offices deducted Church tax from taxpayers, enrolled with a religious body, with the general tax collection by a surcharge on the income tax and then transferred it to the respective religious body. Interfaith mixed marriages, who were taxed as a unit, would have the charged church tax halved among the two respective religious bodies. Mostly the Roman Catholic Church, the respective Protestant regional church bodies and the Jewish congregations (in their case ending by Nazi act in March 1938) collected contributions from their members by way of church tax. Since the Nazis gave the term Mischehe a new meaning the tax offices were ordered to change their terminology to konfessionsverschiedene Ehe (English: denominationally different marriage). Cf. Cornelia SchmitzBerning, Vokabular des Nationalsozialismus, Berlin et al.: de Gruyter, 1998, p. 409. ISBN 3-11-0133792 52. ^ By the "Gesetz zur Vereinheitlichung des Rechts der Eheschließung und der Ehescheidung (EheG)" ("Act on standardisation of the law of contraction and divorce of marriages", as of 6 July 1938) divorce on so-called racial grounds was enabled. Cf. Reichsgesetzblatt (RGBl., i.e. the Reich's law gazette) 1938 I, p. 807, § 37 EheG (Bedeutungsirrtum), cf. also Alexandra Przyrembel, "Rassenschande": Reinheitsmythos und Vernichtungslegitimation im Nationalsozialismus, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003, (Veröffentlichungen des Max-Planck-Instituts für Geschichte; vol. 190), p. 86 (ISBN 3525-35188-7) or - as to contesting or dissolving a marriage - see Bernhard Müller, Alltag im Zivilisationsbruch: Das Ausnahme-Unrecht gegen die jüdische Bevölkerung in Deutschland 1933 1945; eine rechtstatsächliche Untersuchung des Sonderrechts und seiner Folgewirkungen auf den "Alltag" der Deutschen jüdischer Abstammung und jüdischen Bekenntnisses, Munich: Allitera-Verlag, 2003, simultaneously Bielefeld, Univ., Diss., 2002, pp. 344-348. ISBN 3-935877-68-4 53. ^ Based on an evaluation of divorce decrees, however restricted to only one former Reichsgau, the discriminations and easements caused a divorce rate of so-called mixed marriages 20% above the general average. Many divorces followed after the couple succeeded in achieving a visa and thus emigration for the Jewish-classified spouse, so the divorce would lift the discriminations hitting the 17 Aryan-classified spouse, who stayed at home. Cf. Beate Meyer, 'Jüdische Mischlinge' – Rassenpolitik und Verfolgungserfahrung 1933–1945 (11999), Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz, (12002), (Studien zur jüdischen Geschichte; vol. 6), simultaneously Hamburg, Univ., Diss., 1998, ISBN 3-933374-22-7 54. ^ This was maintained by the pre-1939 practice of Jewish congregations in Germany, which denied Jewesses, who married Gentiles, to be precise non-converts to Judaism, to keep their membership in a congregation. This turned the Jewesses, if they did not convert to another faith, legally into irreligionists. While Jews marrying Gentile women could (stay) enroll(ed) as member of a Jewish congregation. 55. ^ Beate Meyer, "Geschichte im Film. Judenverfolgung, Mischehen und der Protest in der Rosenstraße 1943", in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft, vol. 52 (2004), pp. 23-36, footnote 23 on p. 28. ISSN 0044-2828. Some historians judge this intervention of Göring as a tactical measurement, in order not to arouse protests by so-called Aryan kinship, since after secret service reports the government organised November Pogrom in 1938 the regime did not feel so safe about the public's opinion on further antiSemitic discriminations. Cf. Ursula Büttner, "Die Verfolgung der christlich-jüdischen «Mischfamilien»", In: Ursula Büttner, Die Not der Juden teilen. Christlich-jüdische Familien im Dritten Reich. Beispiel und Zeugnis des Schriftstellers Robert Brendel, Hamburg: Christians, 1988, p. 44. ISBN 3-7672-1055-X 56. ^ Cf. Reichsgesetzblatt (RGBl., i.e. the Reich's law gazette) 1939 I, 864 § 7 law text 57. ^ a b Beate Meyer, Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der Hamburger Juden 1933-1945, Landeszentrale für politische Bildung (ed.), Hamburg: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2006, p. 83. ISBN 3929728-85-0 58. ^ Meldungen aus dem Reich: Auswahl aus den geheimen Lageberichten des Sicherheitsdienstes der SS 1939 - 1944 (11965; Reports from the Reich: Selection from the secret reviews of the situation of the SS 1939-1944; 1984 extended to 14 vols.), Heinz Boberach (ed. and compilator), Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag (dtv), 21968, (dtv-dokumente; vol. 477) p. 208. ISBN B0000BSLXR 59. ^ The earlier deportations of Jews and Gentiles of Jewish descent from Austria and Pomerania (both to occupied Poland) as well as Baden and the Palatinate (both to occupied France) had remained a spontaneous episode. 60. ^ At the Wannsee Conference the participants decided to include persons classified as Jews, but married to persons classified as Aryans, however, only after a divorce. In October 1943 an act, facilitating compulsory divorce imposed by the state, was ready for appointment, however, Hitler never granted the competent referees an audience. Pressure by the NSDAP headquarters in early 1944 also failed. Cf. Uwe Dietrich Adam, Judenpolitik im Dritten Reich, Düsseldorf: 2003, pp. 222-234. ISBN 3-7700-4063-5 61. ^ In summer 1945 all in all 8,000 Berliners, whom the Nazis had classified as Jews because of 3 or 4 grandparents survived. Their personal faith - like Jewish, Protestant, Catholic or irreligionist - is mostly not recorded, since only the Nazi files report on them, which use the Nazi racial definitions. 4,700 out of the 8,000 survived due to their living in a mixed marriage. 1,400 survived hiding, out of 5,000 who tried. 1,900 had returned from Theresienstadt. Cf. Hans-Rainer Sandvoß, Widerstand in Wedding und Gesundbrunnen, Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand (ed.), Berlin: Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand, 2003, (Schriftenreihe über den Widerstand in Berlin von 1933 bis 1945; No. 14), p. 302. ISSN 01753592 62. ^ Cf. the Bundesgesetz über die Anerkennung freier Ehen (as of 23 June 1950, Federal law on recognition of free marriages). 63. ^ Rita M. Byrnes, ed. (1996), "Legislative Implementation of Apartheid", South Africa: A Country Study, Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, http://countrystudies.us/south-africa/25.htm, retrieved 2008-01-04 [edit] References "Jack Johnson and White Women: The National Impact", Al-Tony Gilmore, Journal of Negro History (Vol. 58, No. 1, 18-38, Jan., 1973). 18 [edit] External links Loving v. Virginia (No. 395) Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute Loving at Thirty by Harvard Law School Professor Randall Kennedy at SpeakOut.com Loving Day: Celebrate the Legalization of Interracial Couples "The Socio-Political Context of the Integration of Sport in America", R. Reese, Cal Poly Pomona, Journal of African American Men (Volume 4, Number 3, Spring, 1999) [show] v•d•e Segregation in countries by type Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-miscegenation_laws" Categories: Racism | Multiracial affairs | History of racial segregation in the United States | Proposed amendments to the United States Constitution | Race legislation in the United States | United States repealed legislation Hidden categories: Articles containing explicitly cited English language text | All articles with unsourced statements | Articles with unsourced statements from September 2008 | Articles with unsourced statements from April 2009 | Articles with unsourced statements from March 2009 | Articles with unsourced statements from February 2007 | Articles with unsourced statements from December 2009 | All accuracy disputes | Articles with disputed statements from September 2009 | Articles containing German language text Views Article Discussion Edit this page History Personal tools Try Beta Log in / create account Navigation Search Main page Contents Featured content Current events Random article 19 Go Search Interaction About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Contact Wikipedia Donate to Wikipedia Help Toolbox What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Printable version Permanent link Cite this page Languages Português This page was last modified on 8 January 2010 at 20:05. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. See Terms of Use for details. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. Contact us Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers < http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-miscegenation_laws >