7.1 T Roosevelt 1 overemphasized

advertisement

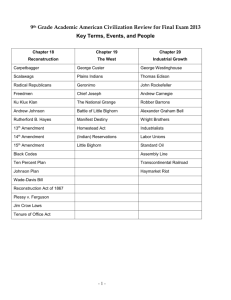

AP US History Document Based Question Directions: The following question requires you to construct an essay that integrates your interpretation of Documents A-O and your knowledge of the period referred to in the question. In the essay you should strive to support your assertions both by citing key pieces of evidence from the documents and by drawing on your knowledge of the period. The impact of Theodore Roosevelt has been overemphasized. He merely took the nation in the directions it was already headed rather than “changing forever the focus and direction of the United States in both foreign and domestic affairs” as one enthusiastic biographer put it. Assess the validity of this statement. Document A Document B “I beg of you not to be discouraged. The rights and interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for--not by the labor agitators, but by the Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given the control of the property interests of the country, and upon the successful management of which so much depends. Do not be discouraged. Pray earnestly that right may triumph, always remembering that the Lord God Omnipotent still reigns, and that His reign is one of law and order, and not of violence and crime. Yours truly, George F. Baer, President” Literary Digest 25 (August 30, 1902): 258. A photostatic copy of the letter is in Caro Lloyd, Henry Demarest Lloyd (New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1912), vol. 2, p. 190 Document C “In Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress you may recall the description of the Man with the Muck-rake [manure rake], the man who could look no way but downward, with the muck-rake in his hand; who was offered a celestial crown for his muck-rake, but who would neither look up nor regard the crown he was offered, but continued to rake himself the filth of the floor. In Pilgrim's Progress the Man with the Muckrake is set forth as the example of him whose vision is fixed on carnal instead of on spiritual things. Yet he also typifies the man who in this life consistently refuses to see aught that is lofty, and fixes his eyes with solemn intentness only on that which is vile and debasing. There are--in the body politic, economic, and social--many and grave evils, and there is urgent necessity for the sternest war upon them. There should be relentless exposure of and attack upon every evil man, whether politician or businessman; every evil practice, whether in politics, in business, or in social life. I hail as a benefactor every writer or speaker, every man who, on the platform, or in book, magazine, or newspaper, with merciless severity makes such attack, provided always that he in his turn remembers that the attack is of use only if it is absolutely truthful. . . . . An epidemic of indiscriminate assault upon character does no good, but very great harm. The soul of every scoundrel is gladdened whenever an honest man is assailed, or even when a scoundrel is untruthfully assailed. . . . One of the chief counts against those who make indiscriminate assault upon men in business or men in public life is that they invite a reaction which is sure to tell powerfully in favor of the unscrupulous scoundrel who really ought to be attacked, who ought to be exposed, who ought, if possible, to be put in the penitentiary.” The American Pageant, Document, Chapter 32. Document D “As to the forest reserves, their creation has damaged just one class, that is, the great lumber barons: the managers and owners of those lumber companies which by illegal, fraudulent, or unfair methods have desired to get possession of the valuable timber of the public domain, to skin the land, and to abandon it when impoverished well-nigh to the point of worthlessness. There are some small men who have wanted to get hold of this lumber land for improper purposes, but they are not powerful or influential, and though they have sometimes been put forward to cause an agitation, the real beneficiaries of the destruction of the forest reserves would be the great lumber companies, which would speedily monopolize them. If it had not been for the creation of the present system of forest reserves, practically every acre of timberland in the West would now be controlled or be on the point of being controlled by one huge lumber trust.” Reprinted by permission of the publishers from The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Volume II, edited by Elting E. Morison, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, Copyright (c) 1951 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Document E “My dear Dr. Shaw: I enclose you, purely for your own information, a copy of a letter of September 5th from our Minister to Colombia. I think it might interest you to see that there was absolutely not the slightest chance of securing by treaty any more than we endeavored to secure. The alternatives were to go to Nicaragua, against the advice of the great majority of competent engineers--some of the most competent saying that we had better have no canal at this time than go there--or else to take the territory by force without any attempt at getting a treaty. I cast aside the proposition made at this time to foment the secession of Panama. Whatever other governments can do, the United States cannot go into the securing by such underhand means, the secession. Privately, I freely say to you that I should be delighted if Panama were an independent State, or if it made itself so at this moment; but for me to say so publicly would amount to an instigation of revolt, and therefore I cannot say it.” Reprinted by permission of the publishers from The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, Volume II, edited by Elting E. Morison, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, Copyright (c) 1951 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Document F “It is not true that the United States feels any land hunger or entertains any projects as regards the other nations of the Western Hemisphere, save such as are for their welfare. All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly, and prosperous. Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon our hearty friendship. If a nation shows that it knows how to act with reasonable efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power. If every country washed by the Caribbean Sea would show the progress in stable and just civilization which, with the aid of the Platt amendment, Cuba has shown since our troops left the island, and which so many of the republics in both Americas are constantly and brilliantly showing, all question of interference by this Nation with their affairs would be at an end. Our interests and those of our southern neighbors are in reality identical. They have great natural riches, and if within their borders the reign of law and justice obtains, prosperity is sure to come to them. While they thus obey the primary laws of civilized society, they may rest assured that they will be treated by us in a spirit of cordial and helpful sympathy. We would interfere with them only in the last resort, and then only if it became evident that their inability or unwillingness to do justice at home and abroad had violated the rights of the United States or had invited foreign aggression to the detriment of the entire body of American nations. It is a mere truism to say that every nation, whether in America or anywhere else, which desires to maintain its freedom, its independence, must ultimately realize that the right of such independence cannot be separated from the responsibility of making good use of it.” A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents (New York: Bureau of National Literature, 1906) vol. 16 (December 6, 1904), pp. 7053-7054. Document G “In order that the best results might follow from an enforcement of the regulations, an understanding was reached with Japan that the existing policy of discouraging the emigration of its subjects of the laboring classes to continental United States should be continued and should, by cooperation of the governments, be made as effective as possible. This understanding contemplates that the Japanese Government shall issue passports to continental United States only to such of its subjects as are nonlaborers or are laborers who, in coming to the continent, seek to resume a formerly acquired domicile, to join a parent, wife, or children residing there, or to assume active control of an already possessed interest in a farming enterprise in this country; so that the three classes of laborers entitled to receive passports have come to be designated "former residents," "parents, wives, or children of residents," and "settled agriculturists." With respect to Hawaii, the Japanese Government stated that, experimentally at least, the issuance of passports to members of the laboring classes proceeding thence would be limited to "former residents" and "parents, wives, or children of residents." The said government has also been exercising a careful supervision over the subject of the emigration of its laboring class to foreign contiguous territory [Mexico, Canada].” The American Pageant, Document Chapter 31. Document H Document I “ The object of government is the welfare of the people. The material progress and prosperity of a nation are desirable chiefly so long as they lead to the moral and material welfare of all good citizens. Just in proportion as the average man and woman are honest, capable of sound judgment and high ideals, active in public affairs. . . . . We must have — I believe we have already — a genuine and permanent moral awakening, without which no wisdom of legislation or administration really means anything; and, on the other hand, we must try to secure the social and economic legislation without which any improvement due to purely moral agitation is necessarily evanescent. . . . . No matter how honest and decent we are in our private lives, if we do not have the right kind of law and the right kind of administration of the law, we cannot go forward as a nation. That is imperative; but it must be an addition to, and not a substitute for, the qualities that make us good citizens. In the last analysis, the most important elements in any man's career must be the sum of those qualities which, in the aggregate, we speak of as character. If he has not got it, then no law that the wit of man can devise, no administration of the law by the boldest and strongest executive, will avail to help him. We must have the right kind of character — character that makes a man, first of all, a good man in the home, a good father, and a good husband — that makes a man a good neighbor. You must have that, and, then, in addition, you must have the kind of law and the kind of administration of the law which will give to those qualities in the private citizen the best possible chance for development. The prime problem of our nation is to get the right type of good citizenship, and, to get it, we must have progress, and our public men must be genuinely progressive.” “Theodore Roosevelt on the New Nationalism” — Part 2, 1910 Document J “Mr. Roosevelt attached to his platform some very splendid suggestions as to noble enterprises which we ought to undertake for the uplift of the human race; but when I hear an ambitious platform put forth, I am very much more interested in the dynamics of it than in the rhetoric of it. . . . You know that Mr. Roosevelt long ago classified trusts for us as good and bad, and he said that he was afraid only of the bad ones. Now he does not desire that there should be any more bad ones, but proposes that they should all be made good by discipline, directly applied by a commission of executive appointment. All he explicitly complains of is lack of publicity and lack of fairness; not the exercise of power, for throughout that plank the power of the great corporations is accepted as the inevitable consequence of the modern organization of industry. All that it is proposed to do is to take them under control and regulation. . . . If the government is to tell big business men how to run their business, then don't you see that big business men have to get closer to the government even than they are now? Don't you see that they must capture the government, in order not to be restrained too much by it? . . . I don't care how benevolent the master is going to be, I will not live under a master. That is not what America was created for. America was created in order that every man should have the same chance as every other man to exercise mastery over his own fortunes. . . . It is perfectly clear to every man who has any vision of the immediate future, who can forecast any part of it from the indications of the present, that we are just upon the threshold of a time when the systematic life of this country will be sustained, or at least supplemented, at every point by governmental activity. And we have now to determine what kind of governmental activity it shall be; whether, in the first place, it shall be direct from the government itself, or whether it shall be indirect, through instrumentalities which have already constituted themselves and which stand ready to supersede the government. . . . . . We do not want a benevolent government. We want a free and a just government. Every one of the great schemes of social uplift which are now so much debated by noble people amongst us is based, when rightly conceived, upon justice, not upon benevolence. It is based upon the right of men to breathe pure air, to live; upon the right of women to bear children, and not to be overburdened so that disease and breakdown will come upon them; upon the right of children to thrive and grow up and be strong; upon all these fundamental things which appeal, indeed, to our hearts, but which our minds perceive to be part of the fundamental justice of life.” Woodrow Wilson, The New Freedom: A Call for the Emancipation of the Generous Energies of a People, William Bayard Hale, ed. (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Page, 1913), pp. 191-222. Document K FOR the Construction of a Ship Canal to Connect the Waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Signed at Washington, November 18, 1903. By the President of the United States of America. Whereas, a Convention between the United States of America and the Republic of Panama to insure the construction of a ship canal across the isthmus of Panama to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, was concluded and signed by their respective Plenipotentiaries at Washington, on the eighteenth day of November, one thousand nine hundred and three, the original of which Convention, being in the English language, is word for word as follows: The United States of America and the Republic of Panama being desirous to insure the construction of a ship canal across the Isthmus of Panama to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, and the Congress of the United States of America having passed an act approved June 28, 1902, in furtherance of that object, by which the President of the United States is authorized to acquire within a reasonable time the control of the necessary territory of the Republic of Colombia, and the sovereignty of such territory being actually vested in the Republic of Panama. . . . The President of the United States of America, John Hay, Secretary of State, and The Government of the Republic of Panama, Philippe Bunau-Varilla, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of the Republic of Panama, there unto specially empowered by said government, who after communicating with each other their respective full powers, found to be in good and due form, have agreed upon and concluded the following articles. . . . .”:Theodore Roosevelt, “Convention Between U. S. And Panama,” Harvard Classics (1910), Vol.43, Pg.479. Document L Document M “In the first case to arise under the Sherman Antitrust Act, United States v. E. C. Knight Co. (1895), the government attempted to dissolve a monopoly of sugar processing, charging the American Sugar Refining Company with illegally restraining trade across state lines. The fact that an article was manufactured for export to another state, said the Court, did not make it part of interstate commerce. Within a few years, however, the justices began to retreat from a rigid transportation/manufacturing distinction when in Swift & Co. v. United States (1905) they agreed unanimously that a price-fixing arrangement among meat packers, although done locally, was indeed a restraint on commerce. Promulgating the "stream of commerce" theory, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, writing for the Court, emphasized that the movement of cattle from one state to another for meat processing and subsequent shipment of meat to other parts of the country constituted a "typical, constantly recurring course", a current or stream of commerce, and the effect of local price-fixing upon interstate commerce was not "accidental, secondary, remote or merely probable.” Hall, Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court, p. 121. Document N “The national verdict of 1896 has for the most part been executed. Whatever remains unfulfilled is a continuing obligation resting with undiminished force upon the Executive and the Congress. But fortunate as our condition is, its permanence can only be assured by sound business methods and strict economy in national administration and legislation. We should not permit our great prosperity to lead us to reckless ventures in business or profligacy in public expenditures. While the Congress determines the objects and the sum of appropriations, the officials of the executive departments are responsible for honest and faithful disbursement, and it should be their constant care to avoid waste and extravagance. William McKinley, Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1901. Document O “After all, how near one to the other is every part of the world. Modern inventions have brought into close relation widely separated peoples and make them better acquainted. Geographic and political divisions will continue to exist, but distances have been effaced. Swift ships and fast trains are becoming cosmopolitan. They invade fields which a few years ago were impenetrable. The world's products are exchanged as never before and with increasing transportation facilities come increasing knowledge and larger trade. Prices are fixed with mathematical precision by supply and demand. The world's selling prices are regulated by market and crop reports. We travel greater distances in a shorter space of time and with more ease than was ever dreamed of by the fathers. Isolation is no longer possible or desirable. The same important news is read, tho in different languages, the same day in all Christendom. The telegraph keeps us advised of what is occurring everywhere, and the press foreshadows, with more or less accuracy, the plans and purposes of the nations. Market prices of products and of securities are hourly known in every commercial mart, and the investments of the people extend beyond their own national boundaries into the remotest parts of the earth. Vast transactions are conducted and international exchanges are made by the thick of the cable. Every event of interest is immediately bulletined. The quick gathering and transmission of news, like rapid transit, are of recent origin, and are only made possible by the genius of the inventor and the courage of the investor. It took a special messenger of the government, with every facility known at the time for rapid travel, nineteen days to go from the City of Washington to New Orleans with a message to General Jackson that the war with England had ceased and a treaty of peace had been signed. How different now! We reach General Miles, in Porto Rico, and he was able through the military telegraph to stop his army on the firing line with the message that the United States and Spain had signed a protocol suspending hostilities. We knew almost instantly of the first shots fired at Santiago, and the subsequent surrender of the Spanish forces was known at Washington within less than hour of its consummation. The first ship of Cervera's fleet had hardly emerged from that historic harbor when the fact was flashed to our Capitol, and the swift destruction that followed was announced immediately through the wonderful medium of telegraphy.” McKinley, His Last Speech, The World's Famous Orations, Vol.3, Pg.242