Consumerism and Heritage in Puerto Rican Brujería

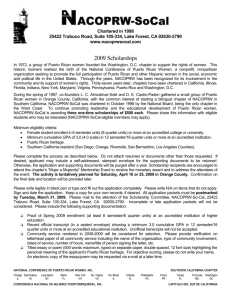

advertisement

Raquel Romberg Glocal Spirituality: Consumerism and Heritage in Puerto Rican Brujería1 Prepared for the Penn 40th Conference April 2-3, 2004 Over the span of five centuries, various layered histories originating in distant places have shaped the practices of Puerto Rican brujería (witch-healing). In this tortuous history brujería has incorporated at different periods the gestures of popular Spanish Catholicism, French Spiritism (encoded by Allan Kardec as Scientific Spiritism or Espiritismo Científico), folk American Protestantism, and Cuban Santería. These religious practices met as the result of political, economic and social conditions brought by colonialism, slavery, nation building, and migration. After centuries of gradual change, the practices of brujería have recently changed again as a result of colonial relations that tie the US mainland with the island under the commonwealth status. These ties, which began with the American invasion of 1898, are ideological and cultural, not only economic; they have transformed Puerto Rican modes of production and consumption under free trade and consumerism, helped forge a particular form of cultural nationalism, as well as changed the institutional and ideological role of the state, operating under the commonwealth system of welfare capitalism. With the recent intensification of the circulation of ritual experts and commodities, folk religions such as Puerto Rican brujería have entered a transnational arena of ritual experimentation and eclecticism. Concomitantly, the politics of identity, operating at local-political and global-commercial stages, have propelled the search for origins and the production of essential identities, leading to the revitalization and orthodoxy of folk religions as well as their folklorization, following a local—though globally pervasive— heritage discourse. Why glocal spirituality? My main argument is that both these forces—the actual insertion into global circulations that promote a high degree of ritual eclecticism and the local demand for an essential Puerto Rican national identity that promote orthodoxy work in tandem, creating a complex set of esthetic ecologies intimately connected to economic and public spheres of action that provide the choices for vernacular ritual practice and meaning. 1 This essay is based on a chapter forthcoming in Contemporary Caribbean Societies and Cultures, edited by Franklin W Knight and Teresita Martínez Vergne, North Carolina University Press. An earlier version, “Glocal Folk Religions: Eclecticism and Orthodoxy in Puerto Rican Witch-Healing,” was presented at the panel “Cultural Circulations: Fetishes, Phantasms, Idealizations and Other Instabilities” at the 2003 AFS meeting in Chicago. I want to thank Amy Shuman for organizing the panel and suggesting an exciting problematic, and our discussant, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, for her insightful and passionate comments. My appreciation also goes to Margaret Mills for providing the opportunity and encouragement for my initial thoughts on future contributions of folklore to globalization theories and methodologies at a forum she organized at a Political Science symposium at Penn in 1996, and to Roger Abrahams, whose work and conversation have been a constant source of inspiration. How can these apparently contradictory processes—extreme deterritorialization and circulation of ritual experts, commodities and practices, and the re-centering of these practices within nationalist agendas— be theorized within folklore studies? How can we theorize the simultaneous rupture and revaluation of the emblematic connection between land, people and lore? By means of a historic-pragmatic perspective to ritual and an intimate ethnographic account that traces the encounters between practitioners, clients, and suppliers of ritual goods I show how these two apparently opposing processes work in tandem: the homogeneity produced by consumer capitalism, and the end of the nation with globalization—theoretical fictions. That is, without an a-priori recognition of brujos (witch-healers) in the public sphere as repositories of Puerto Rican wisdom (in the context of the unresolved neocolonial political status of the island), the fame and celebrity that enabled the open incorporation of African based rituals, of bureaucratic gestures and interventions, and transnational religious commodities could not have been viable. Also, the entrepreneurial aspect of this form of spirituality has lead to a strategic integration of transnational deities and healing and magic rituals, all the while brujos were gaining an unprecedented revalorization in the public sphere as representatives of “our nation.” This did not prevent, however, clients from rewarding brujos who had proved their success and professionalism by tapping into a transnational area of ritual expertise in line with, not opposition to, both mainstream consumer and multicultural ideologies. Critics of the culture industry and consumerism (and also some trends within folklore studies) tend to suggest that commercial forces inherently taint the authenticity of culture, and in this case would taint the spiritual effectiveness of brujería. For practitioners and clients, however, material and spiritual progress not only are not at odds but also are intimately connected. Indeed, practitioners are driven by the attainment of “blessings”— defined by material success as well as spiritual power—which presume the spirituality of commodities and the thinghood of spirituality. Especially in a world guided by capitalist modes of production and the sensuous insatiable consumption of life styles and selfimages, brujos and their clients take advantage of the opportunities opened up by the ideology of multiculturalism and identity politics. They openly expand the pantheon of spirits as well as their ritual expertise, protected by the idiom of heritage—yet outside of its constraints—showing that more than endangered species they are active participants in these glocal forces, speaking to them in their own particular modern yet spiritual idiom. This ethnographic reality—which is not unique to Puerto Rico in its totality, nor exclusive in its glocality to religious practices or the present —points to the complex interface of various, even contradictory sets of practices (e.g. here, guided by discourses of consumerism and heritage), which—to complicate matters even more—operate at various individual, commercial and public circuits. The challenge for folklorists today is to integrate previous scholarship traditions on each of these levels of inquiry (for instance in this case, but not restricted to, consumerism, nationalism, heritage, performance) in moving along and in-between these ecologies; to trace the emergence of glocal sites equipped with a particular methodology and lens for each; and lastly, to entertain new theoretical formulations that might cross-over (for lack of a better word) conventionally unconnected theoretical traditions. Raquel Romberg is the author of Witchcraft and Welfare: Spiritual Capital and the Business of Magic in Modern Puerto Rico, University of Texas Press, 2003. Currently, she is assistant professor of anthropology at Temple University. rromberg@temple.edu