Paper - ILTA

advertisement

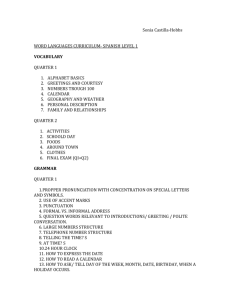

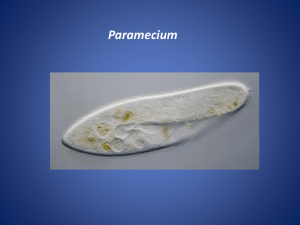

Operation Conjugation! A Game Based learning approach to language studies Cathal McCosker Digital Enterprise Research Institute & National University of Ireland, Galway cathal.mccosker@deri.org Supervisors: Tony Hall (NUIG, School of Education), Edward Curry (DERI), Stefan Decker (DERI) Paper Type: Postgraduate Keywords: Digital Game Based Learning, Game Design, Language Studies, Operation Conjugation, Behaviourism, Constructivism Abstract: The use of multimedia games presented in a fun and engaging environment can satisfy important learning principles such as attention, motivation, reflection, assessment and feedback. This learning environment can be used to assist in the teaching of language studies which can lead to an improvement in academic performance (attention and recall). The current education system utilises traditional teaching techniques such as trail and error, rote teaching and the “take once and succeed” model. Although these techniques worked, they did so in a limited fashion as they used passive teaching rather than engaging the students with the subject. New teaching techniques have evolved which focus more on the nature of human thinking and learning. Students that do not respond well to the traditional teaching techniques require alternative education practices to engage them with learning. Teachers have taught subjects through practical games to make the subject more engaging, competitive and fun for the classroom. This would relieve the class from the boredom of “skill and drill” and “chalk and talk” and engage them with learning the subject. Games serve a range of educational principles and create a positive psychological impact, while getting the information across (Mitchell, Savill-Smith (2004)). Commercial video games use techniques (e.g. coaching, accommodation, reflection, instant feedback, zone of proximal development, black boxing, flow, time compression, productive failure) that match up very well with the latest in cognitive research on how people think and learn. (Squire (2005)). However, not much progress has been made in creating an educational video game which incorporates these learning principles and teaches academic subjects. Instead early elearning ventures became digitised “chalk and talk” ignoring the potential of games to present subjects in interesting abstract ways. I have developed a prototype game which allows students to practice regular French verb conjugation, harnessing the motivational power of games in order to make learning fun, in an exciting and engaging environment. The overall project is an exploration of teaching and learning techniques, integrated into a prototype program. This program will test the claims behind game based learning by testing its capability on students. The guidelines for the game’s development could be adapted to other learning programs. The latest cognitive techniques would be difficult to implement in traditional schools without the need to train the teacher. Game based learning offers a portable, viable solution to re-training staff. Given the interactivity and multimedia aspect of computer games, they hold attention for longer than traditional techniques, and can give the student the motivation they need to complete the learning process. The learning theories that have been researched (Watson (1913), Vygotsky (1978), Malone (1980), Csikszentmihalyi (1990), Di Vesta (1987)), show requirements for learning, which proper design of game based learning programs can satisfy (Gagne (1985), Herrington and Oliver (1995), McKenna and Laycock (2004), DeCorte (1990)) 1. Introduction Recently game based learning has been given a new edge by the computer games industry. Due to the advances of this industry, the potential of digital game based learning (DGBL) has come into the public awareness. This paper describes the development and use of multimedia computer games to assist in the study of language studies, specifically regular French verb conjugation. It introduces a number of pedagogical theories which were examined in order to gain an understanding of the fundamental principles of learning. These theories were studied for applicable practices which would influence the design of digital games for learning 2. Learning Theories: 2.1 Behaviourism & Constructivism The behaviourist learning principles of trail and error and using consequences to modify behaviour are still in use by academic institutions today, and were considered to be a fundamental part of “Operation Conjugation!” if the game were to efficiently transfer information from the game to the student. “Operation Conjugation!” takes on the role as the teacher/facilitator supporting the constructivist problem-based and inquiry learning methods allowing users to guess and try again even when they have failed. This idea creates a “psychosocial moratorium” (Gee 2003) an environment in which, learners are encouraged to take risks and where real world consequences are lowered. This environment promotes the student to intelligently guess an answer without fear of instant failure, supporting Brown’s (1989) idea of the importance of guesswork. Using immersive gameplay the student’s attention is centred on the game, they are actively participating in the subject and guided by means of instant feedback, reflection and visual cues, at each part of the conjugation process. These DGBL approaches accommodate Di Vesta’s (1987) idea of supporting and challenging the student. Rather than being a passive recipient of information the student is now an active participant in the learning process. The game indicates via visual/audio cues and instant feedback whether the student is correct or not which requires the student to reflect on their actions if they are incorrect. The incremental difficulty levels in “Operation Conjugation!” link up with Vygotsky’s (1978) ZPD. By successfully completing difficult tasks, learners gain confidence and motivation to embark on more complex challenges. This concept also complements von Glaserfeld’s (1989) concept that an improvement in the student’s confidence in their own learning ability effects their motivation to complete the task. 2.2 Digital Game Based Learning Ever since the earliest development of computer games, there has been interest in the medium as a new opportunity for learning (Greenfield 1984). Although the practical development of DGBL is in its infancy in recent years many papers on the educational development and design of games to aid in learning have emerged (K. Corti 2006, A. McFarlane 2004, M. Oehlert 2005, Gee 2003, Prensky 2001, Kafai 2001, Loftus & Loftus 1983, Malone 1987). Commercial “edutainment” titles have been unsuccessful in harnessing their potential for educational use (McFarlane & Kirriemuir 2004) and Papert described “edutainment” as the “offspring that keep the bad features of each parent and lose the good ones” (Papert 1998). However, some progress has been made creating the right mix in computer games for learning, which effectively incorporates learning principles, assists in learning academic subjects and motivates students while capturing their imagination and attention. Figure 1: “Zombie Division” (Habgood et al. 2005) Figure 1 shows Jake Habgood’s research on “Zombie Division” where children have to perform division tasks in order to fight skeletal enemies. His work resulted in evaluating games as “offering a significant boost to the fatigue and apathy created by the frequency of testing in the education system, Habgood states that “the real educational potential of games is almost certainly outside of the classroom … the motivational appeal of games means that many children will willingly choose to engage with them in their own free time, and these studies have demonstrated the superior appeal of intrinsic games.” (Habgood 2007) 3. Game Design 3.1 Game Types Oehlert (2005) describes the broad agreement on the game styles which generally map best to learning content. Learning Content Facts Skills Procedures and Processes Behaviours and Reasoning Learning Activities Questions, memorisation, drill, association Imitation, feedback, coaching, continuous practice, increasing challenge Analysis, Practice Imitation, feedback, coaching, practice, problems, examples Table 1: Game Types Game Style Game Shows, flash cards, mnemonics Role-Playing, simulations, count-down/timed games, twitch games Strategy Games, Adventure Games Role-Playing, Simulations, Puzzle Games From the learning principles covered in section two, we can match up these required principles for learning with the learning activities within role playing or simulation games. “Operation Conjugation!” will therefore need to include features of both role playing and simulation games where the user can take control of a character in order to train their conjugation skills in a virtual environment. 3.2 Game Design Concepts A body of research on how to design game based learning is available (Gagne 1985, Malone 1980, Csikszentmihalyi 1990, Herrington and Oliver 1995, McKenna and Laycock 2004), through deliberation on how to design the “Operation Conjugation!” a mixture between instructivist and social constructivism; incorporating the attributes from both, was chosen. The theory behind instructivism includes behaviourism, objectivism and operant conditioning. The behaviourist model dissects the problem into logical parts or small units and provides the student with steps to follow, rewarding the student for progress. Kirriemuir and McFarlane (2004) discuss the social constructivism of children and game play. Their review of the literature highlights the way in which children take on the role of teachers, providing advice, support, hints, tips and models of learning to other children. Inkpen et al (1995) found that when children played ‘The Incredible Machine’, a problem-solving game, together on one machine, they 'solved significantly more puzzles than children playing alone on one machine'. They were also more motivated to continue playing when they had a human partner. “Operation Conjugation” needed to incorporate a collaborative two player design which allows for social constructivism. 4. Operation Conjugation! The game has been designed to develop the student’s proficiency in conjugating regular French verbs while creating a positive learning experience. This technology is not viewed as a replacement of traditional teaching but as an enhancement tool for practicing verb conjugation. The game itself has two modes. When played in a liner fashion these practice modes fully test the student’s knowledge of regular French verb conjugation. The in game tutorials are interactive rolling demos of each part of the game, with information and highlighting for the student to click through. 4.2 Practice Game The first mode is a “point and click” practice level where the student must prove their competence in remembering the French verb endings. Figure 2: Practice Game If a student fails to remember what verb ending is correct, the built in help function in the form of the French character “Jacques” appears in the bottom left hand corner to give assistance to the student. If the student fails to guess the answer within three tries, the question is saved and asked again at the end of the practice session. Once the student has completed the practice level they can move on to the second mode, the main game. 4.3 Main Game The original concept of the main game is based on “Oil Panic” released for the Nintendo Game and Watch series. Figure 3: “Oil Panic” & Operation Conjugation’s Main Game In “Oil Panic” the character had to catch oil dripping from the ceiling in a can and pass it to a second character outside, who empties the oil can. In Operation Conjugation’s main game the character has to catch falling verbs that are launched into the sky and conjugate the verb properly before giving it to the bottom character to complete the conjugation. It is composed of three different levels of difficulty that incrementally takes the user through the game only proceeding to the next level when they have successfully achieved competence of the level. This game can be either one player (i.e. controlling both characters) or two player (i.e. controlling one character each). 5. Conclusions Initial testing of “Operation Conjugation!” has shown positive results. In house testing revealed a positive reception to the game, with neutral feelings on the tutorials along with positive academic performance. Attention and motivation was gauged in a questionnaire after game completion, ranging from constant attention to immersed, all participants reported to be fairly motivated during the session. Overall rating of the game was good to very good, with all participants reporting that they would play the game again. Comparing this to a questionnaire after traditional text based study has shown that some participants felt their attention slipping during studying, with one participant not enjoying the session. Full scale tests are currently under way, with participants that meet the games target criteria. Some informal feedback from the students was gathered, when asked if the participants liked the game, an enthusiastic response occurred with all participants admitting that they would use the program over text based study to practice for an upcoming test. 6. References Brown, J. S., Collins, A., and Duguid, P., (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32-42. Corti, K., (2006). Game-based learning; A serious business application. PIXELearning. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990), Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. De Corte, E., (1990). Towards powerful learning environments for the acquisition of problem solving skills. European Journal of Psychology of Education 5: 5-19. Di Vesta, F. J., (1987). The Cognitive Movement and Education. In J. A. Glover & R. R. Ronning (Eds.), Historical Foundations of Educational Psychology (pp. 203-233). New York: Plenum Press., Gagne, R. M., Briggs, Leslie, J., Wager, Walter, F., (1985). Principles of Instructional Design. Gee, J. P., (2003). What computer games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Habgood, M. P. J., (2007). The effective integration of digial games and learning content. PhD Thesis, University of Nottingham, Habgood, M. P. J., Ainsworth, S., and Benford, S., (2005). Zombie Division: Intrinsic integration in digital learning games. Nottingham, UK (Learning Sciences Research Institute, The University of Nottingham, Jubilee Campus, Wollaton Road, Nottingham). Herrington, J. and Oliver, R., (1995). Critical characteristics of situated learning: Implications for the instructional design of multimedia. Learning with technology (pp. 235-262). Inkpen, K., Booth, K., Klawe, M., et al., (1995). Playing Together Beats Playing Apart, Especially for Girls. Proceedings of Computer Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) '95. Kafai, Y. B., (2001). The educational potential of electronic games: From games-toteach to games-to-learn. [Online] 30th April 2009, <www.savie.ca/SAGE/Articles/1232-KAFAi-2001.pdf>, Loftus, G. R. and Loftus, E. F., (1983). Mind at play. The psychology of video games. New York, Basic Books Malone, T. W., (1980). What makes things fun to learn? Heuristics for designing instructional computer games. Paper presented at the Association for Computer Machinery Symposium on Small and Personal Computer Systems, Pal Alto, California, Malone, T. W. and Lepper, M. R., (1987). Making learning fun: A taxonomy of intrinsic motivations for learning. R. E. Snow & M. J. Farr (Eds), Aptitude, Learning and Instruction: III. Conative and affective process analyses (pp. 223-253). Hilsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, McFarlane, A. and Kirriemuir, J., (2004). Literature Review in Games and Learning. FutureLab. McKenna, P. and Laycock, B., (2004). Constructivist or Instructivst: Pedagogical Concepts Applied to a Computer Learning Environment. ITICSE 04. Mitchell, A. and Savill-Smith, C., (2004). The use of computer games for learning – A review of the literature. Oehlert, M., (2005). Gaming for learning On-Ramp paper. Masie Consortium. Papert, S., (1998). Does easy do it? Children, games and learning. Game Developer, June 1998, 87-88. Prensky, M., (2001). Digital Game-Based Learning. McGraw-Hill Squire, K., (2005). Game Based Learning. Masie Center E-learning Consortium. von Glasersfeld, E., (1989). Cognition, construction of knowledge and teaching. Synthese, 80, 121-140. Vygotsky, L., (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Watson, J. B., (1913). Psychology as the Behaviourist views it.