Part II: Fossil Fuels

advertisement

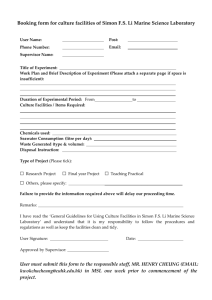

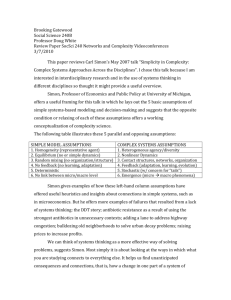

Fall AY2016 Part II FE345: Environmental Economics Course Notes Part II: Fossil Fuels S(2): Energy, Technology, and the Environment (FE345 Section only) I. The Environmental Kuznets Curve The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) → Characterizes the (hypothesized) relationship between per capita income in a country and environmental quality in a country over time Tax Credit How is “environmental quality” to be measured? e.g. (domestic) pollution tends to fall at high levels of economic development, but emission of carbon dioxide increases, and habitat / biodiversity levels tend to decrease (so far) Why should this relationship hold, in theory? 1 Fall AY2016 Part II Does the EKC relationship hold, in reality? → Evidence is mixed (1) Fairly strong evidence that it does for local air / water pollution (2) Lack of evidence that it holds for global air pollutants (CO2) or for biodiversity or natural capital (conservation of forests, water sources, etc, which tend to continue to be exploited as income rises) *** Perhaps the developed world is just now reaching sufficiently high income levels so that there is a demand for lower greenhouse gas emissions, forest conservation, and greater biodiversity. That is, perhaps the exact EKC relationship varies by specific “pollutant” or measure of environmental quality. (3) May be that high income countries never actually reduce their pollution output, they just outsource their pollution and environmental degradation to less-developed countries. (G8) Deriving Energy from Fossil Fuels (Caton Lecture #2) (G9) Fossil Fuels: The Economics of Non-Renewable Energy Resources (Swope Lecture #2) 2 Fall AY2016 II. Part II The Population Question Is the “laissez faire” rate of population growth likely to be efficient? Assuming the decision to have children is a rational, economic decision, consider the economic model of fertility (i.e. how many children to bear): Tax Credit 3 Fall AY2016 Marginal (private) benefit of children (MPB) → Marginal (private) cost of children (MPC) → Shifters of MPB curve → Shifters of MPC curve → Part II 4 Fall AY2016 Part II Are there positive or negative externalities from child bearing? Positive externalities (why MSB > MPB) Negative externalities (why MSC > MPC) 5 Fall AY2016 The “Demographic Transition Model” Compare China’s population policy to that of U.S.: Part II China → “One-child policy” (for urban couples) - Traced to Marxist theories of pop. growth (which originated with Malthus) - Started in 1979; estimated to have led to 300 million fewer births - Criticized by human rights groups (forced sterilizations/abortions; selective gender-based abortions) - Problems → male/female imbalance in population; unregistered children (ineligible for state benefits); “4-2-1” problem (four grandparents, two parents, being cared for by one child) - Benefits → improved health care for women; increased savings rate (fueling economic growth) 6 Fall AY2016 Part II U.S.→ no official policy (but effectively subsidize childbirth in many ways) - Tax exemption for each dependent ($3700) plus child tax credit ($1000, if eligible) plus standard deduction for each dependent ($950) or itemized deductions for dependent care expenses (up to $6000), student loan interest, and some medical expenses. - Military housing allowance based on number of dependents - Welfare (food stamps, housing, cash assistance programs) all based on number of dependents - Public schooling 7 Fall AY2016 Part II The “Simon-Ehrlich Wager” (1980) → Neo-Malthusians vs. Cornucopians Paul Ehrlich (the “Doomsayer”, 1932 - ) Julian Simon (the “Doomslayer”, 1932 – 1998) Biologist Paul Ehrlich (in The Population Bomb (1968)) argued that overpopulation, resource scarcity, and mass starvations were rapidly approaching. Economist Julian Simon disagreed (in The Ultimate Resource (1981)), saying that population growth was beneficial to human well being, and the source of the technological growth that would ultimately make resources less scarce over time. In 1980, Simon challenged Ehrlich to a bet → Ehrlich could pick any non-governmentally controlled commodities and any date at least one year in the future. Simon predicted their prices would be lower in the future than today (in 1980). Ehrlich picked five metals (chromium, copper, nickel, tin, tungsten) and Sept. 29, 1990. He bought $200 worth of each metal, for a total bet of $1000. If the combined price increased, Simon would have to pay Ehrlich the amount of the increase. If their combined price fell, Ehrlich would pay Simon the difference. So what happened? 8 Fall AY2016 Part II “More people, and increased income, cause resources to become more scarce in the short run. Heightened scarcity causes prices to rise. The higher prices present opportunity, and prompt inventors and entrepreneurs to search for solutions. Many fail in the search, at cost to themselves. But in a free society, solutions are eventually found. And in the long run the new developments leave us better off than if the problems had not arisen. That is, prices eventually become lower than before the increased scarcity occurred.” - Julian Simon “The bet doesn't mean anything. Julian Simon is like the guy who jumps off the Empire State Building and says how great things are going so far as he passes the 10th floor. I still think the price of those metals will go up eventually, but that's a minor point. The resource that worries me the most is the declining capacity of our planet to buffer itself against human impacts. Look at the new problems that have come up: the ozone hole, acid rain, global warming. It's true that we've kept up food production -- I underestimated how badly we'd keep on depleting our topsoil and ground water -- but I have no doubt that sometime in the next century food will be scarce enough that prices are really going to be high even in the United States.” - Paul Ehrlich “As soon as one predicted disaster doesn’t occur, the doomsayers skip to another…why don’t [they] see that, in the aggregate, things are getting better? Why do they always think we are at a turning point – or at the end of the road?” - Julian Simon1 1 Simon challenged Ehrlich to a second bet based on measures of human welfare rather than commodity prices, but the two could not agree on the terms of the bet before Simon’s death in 1998. 9 Fall AY2016 Part II Is there an appropriate government policy toward population growth? What role, if any, should the government play? Government’s role will likely vary by country, but… 10 Fall AY2016 III. Part II Agriculture and the Environment Internationally (and in the U.S.) hunger and malnutrition are important and serious problems. Are they getting worse, or better? Were Malthus / Ehrlich right about population growth and the food supply, or was Simon right? World food production per capita has been steadily _______________________________ % of human population that is malnourished has been steadily __________________ % of human population that is obese has been steadily _____________________ (both in wealthy developed countries and in less developed countries) Dramatic increases in agricultural productivity (yield per acre) achieved by Trends in U.S. agriculture Less employment on farms → Figure 1 Fewer, larger farms → Figure 3 Specialization of output → Figure 4 Increased productivity → Figure 5 Increased exports → Figure 6 Increased share of off-farm household income 11 Fall AY2016 Part II Brief history of U.S. farm policy 1930’s → Traditional price supports and supply controls [set-asides] (some continued into 1980’s → Reagan-era “government cheese”, which now seems to refer to any kind of government handout) In response to hardship during Great Depression Many school lunch programs have their origins in attempts to dispose of surplus ag. commodities Tariff controls to prevent imports 1960’s – 1970’s → Introduce “target prices” accompanied by “deficiency payments” In response to large surpluses resulting from productivity increases after WWII Increases reliance on markets (rather than government buying surpluses); encouragement of export growth Served to depress world crop prices, negatively impacting farmers overseas, particularly in developing countries Increased use of “direct payments” to farmers based on historical output and less on current production Has probably reduced inefficiencies from “unnecessary” government intervention; rural “welfare”? 2007 → Biofuel mandates part of the Energy Security and Independence Act According to experts, the mandates have made us no more “secure” or “independent”; have other negative social and environmental impacts (higher food prices; increased water / fertilizer / pesticide / land use and associated negative environmental impacts) Agricultural subsidies also continue to take the form of subsidized crop insurance and subsidized water use Note: By law, U.S. international food aid (distributed by USDA and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) must come from U.S. farmers. U.S. Food Stamp Program (now called “Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program” (SNAP)), administered by USDA, prohibits purchase of imported food with food stamps. High tariffs on ethanol imports (from Brazilian sugar-cane ethanol, in particular) Result is that 1/3 to ½ of farm income in U.S. comes from government subsidies (farmers in Japan typically receive twice as much from government as from farming itself). 12 Fall AY2016 Part II Primary impacts of U.S. farm policy (and typical policies of other developed countries) on developing countries: 1. Restricting imports of commodities in which developing countries have a comparative advantage depresses their domestic prices. 2. Encouraging overproduction and export of U.S. commodities depresses world crop prices 3. Provision of in-kind food aid (produced by U.S. farmers) to developing countries may further distort their markets and depress prices Commodity Percent Price Depressed Rice*** 33 – 50% Sugar 20 – 40% Dairy 20 – 40% Cotton 10 – 20% Peanuts 10 – 20% Source: World Bank *** From 1995 – 2009 nearly $13 billion in rice subsidies paid to U.S. farmers. Since 2000, $1.3 billion paid to people who don’t even farm (and most have household income well in excess of the national average). One Houston surgeon has collected $490,000 (owns property on which rice was grown in the past and qualifies for rice subsidies). Cuts under recent debt reduction legislation call for reductions or elimination of many subsidies. Agricultural policies in developing countries may cause or exacerbate food problems: Price controls often used to make food affordable to the poor (but this lowers the return to farmers) Governments often tempted to purchase cheap imported food or accept food aid to alleviate food shortages in short-run (but this doesn’t help develop domestic food supply) Property rights protections are often weak (or violated by governments themselves (e.g. confiscating property to address social goals or during periods of political unrest, etc). People may simply flee land during civil wars. 13 Fall AY2016 Part II Agricultural production involves many externalities: Negative externalities - Fertilizer, sediment, pesticide / herbicide runoff → damage to insect populations (e.g. bees, etc) and other wildlife (e.g. oysters, blue crabs) - Greenhouse gas emissions - Excessive (common-property) water use for irrigation (if farmers do not bear full marginal social cost of water used) Positive externalities - Farm land provides open space / scenic views - Historical or heritage values - Some benefit of farm land to for wildlife (relative to suburban development); e.g. hawk on alfalfa farm in California - Excess domestic agricultural production may also be justified on food security grounds Predominance of negative externalities suggests government should possibly be taxing farm output (or taxing polluting inputs and water use). Little justification for continued subsidizing of agriculture on efficiency grounds (given the environmental impacts and consequences for international relations). 14 Fall AY2016 IV. Part II Regional and Global Air Pollution Challenges 1. Atmospheric deposition of acid substances (a.k.a. Acid Rain!) Acid rain damage to trees in Great Smoky Mountains Cause: SO2 emissions from coal-fired power plants Solution: SO2 “cap and trade” programs in Europe and U.S. (leading to use of lowsulfur coal, “scrubbers”2, lower electricity use, alternative electricity generation sources → nuclear power, some wind / solar) 2 E.g. “wet” scrubbers, “dry” scrubbers, or “absorbers”. If you are interested in purchasing a “scrubber”, see http://www.hanseneng.com/scrubber.html. 15 Fall AY2016 Part II Acid rain deposition in the USA from 1983 through 1997. From: Driscoll (2001). 16 Fall AY2016 Part II 2. Ozone Depletion False-color view of total ozone over the Antarctic pole. The purple and blue colors are where there is the least ozone, and the yellows and reds are where there is more ozone. Image Source: NASA’s Ozone Hole Watch (updated daily, image from 8/5/14) Cause: Chloroflourocarbons (CFC’s) from aerosols, refrigeration units Solution: Montreal Protocol (1988) and subsequent agreements → called for gradual phase-outs of CFC’s (replacing them with hydrochloroflourocarbons (HCFC’s)); included delayed phase-outs for developing countries and assistance to help with costs; considered a model for international cooperation on global pollution problems. 17 Fall AY2016 Part II 3. Global Climate Change Cause (of anthropegenic portion): “Greenhouse gas” emissions (CO2, methane, NO2, HCFC’s, ozone); land-use changes (more cities, highways), desertification Solution: For each of the following questions, circle “yes” or “no”: (1) Is the temperature of the earth rising? Yes → There is scientific consensus that global temperatures are rising. No → Warming trends have been overly emphasized. Many areas have had no significant change, and some are even getting colder. (2) If the temperature of the earth is rising, is human activity a significant contributing factor? Which activities are contributing to climate change? Yes → Human activities have caused global temperatures to rise beyond any natural background warming that may be occurring. No → Although there has been an upward trend in temperatures, the relationship between this trend and the human activities above is insignificant or non-existent. (3) Would it be technically or scientifically possible for humans to mitigate or reverse global warming? Yes → If the theoretical relationship between climate change and human activities is correct, then a significant amount of climate change could be mitigated. No → Climate change is already well underway, and all potential changes in human activity can have little or no impact on future climatic changes. (4) Globally, would the benefits of mitigating climate change exceed the costs? Yes → The economic damage costs from global warming are likely to be so high, and the mitigation costs sufficiently low, such that the overall benefits of a global mitigation plan will exceed the costs of such a plan. No → Climate change is not a “crisis”; adaptation will be less costly and more pragmatic that costly initiatives to try to prevent or mitigate climate change; costs of mitigating climate change will be immediate, while the “benefits” will only be realized in the distant future. 18 Fall AY2016 Part II (5) If mitigation benefits exceed the costs, is an effective, enforceable, and sustainable international agreement to mitigate climate change obtainable? Yes → the international community has already proven that it can successfully come together to tackle other environmental problems (e.g. addressing the “ozone hole” problem through the Montreal Protocol and the phasing out of CFC’s) No → Costs and benefits are distributed very unevenly internationally, and the organizational costs of establishing an agreement are too high; it will be difficult or impossible to monitor and enforce international agreements; future generations cannot vote now (even if they would get large benefits from mitigating climate change), therefore, political action today is unlikely to be obtained; large revenues from “carbon taxes” or “cap and trade” programs would simply result in larger governments and more corruption. 19 Fall AY2016 V. Part II Climate Change and Cost/Benefit Analysis Questions of science: Is the earth’s climate changing? Is human activity (e.g. greenhouse gas emissions) a significant contributing factor? The first three questions above are science questions. Questions of economics (and/or ethics): Should we take action now to mitigate climate change? Question 4 above is an economics question. Question 5 is a question of both politics and economics. If we take an economic approach to this last question, we face a difficult cost/benefit analysis problem for two reasons: 1. What are the costs and benefits of actions to mitigate climate change? How do we measure them? 2. How do we properly discount costs and benefits that may occur in the distant future? (That is, what should we choose as our discount factor?) A. Time-Value of Money If i is the discount factor3 and t is the number of years, the present discounted value of receiving $C (or other monetary units) at time t is PV C (1 i )t B. Annuities and Perpetuities If you are to receive $C once every year for the next n years (called an annuity), the present discounted value of the annuity would be PV C 1 (1 i ) n i If you are to receive $C once every year indefinitely (called a perpetuity), the present discounted value of the perpetuity would be PV C i 3 The discount rate is often the simple, real, market rate of interest one would expect to receive over the time period in consideration (e.g. 5% or 0.05). The discount rate may or may not be assumed constant over the entire time period. The choice of discount rate for public projects is often the source of controversy. Higher discount rates lower the present value of projects with benefits that occur in the future. 20 Fall AY2016 Part II Some practice problems: 1. A project will have net benefits of $1 million. Complete the following table showing the present discounted value of the benefits occurring at different points in the future and for different discount factors: Discount rate 50 years 100 years 2% 3% 5% 10% 2. You have to replace your hot water heater. You have the two options below. Which one is preferred? Option A: Whirlpool 80-Gallon (6-Year Tank Warranty) Tall Electric Water Heater at Lowes $539 Option B: Marathon 85-gallon (Lifetime Warranty) water heater at Home Depot $1,002 21 Fall AY2016 Part II 22