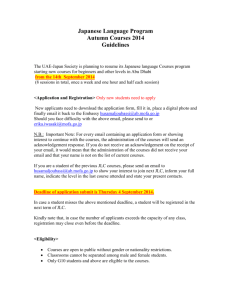

Japanese expressions - Gippsland-Generic-LOTE

advertisement

Here are some explanations of Japanese expressions. They were supplied by Akiko Harada the Tasmanian Japanese Advisor, Japan Foundation. Akiko says that we can see a bit of a different way of thinking of culture. Akiko adapted these from 'Japanese Journal’ issued January 2004. The source of energy : Genki The term ‘genki’ is not simply an antonym for sickness or poor health; it refers to an adequate source of energy for activity. The image is just like that of a container full of fuel. We express having vigour as ‘genki-ippai’(full of life), or ‘genkihatsuratsu’(bursting with energy),. The opposition condition is called ‘genki-ga-nai’ (no pep) or ‘genki ga nakunaru’ (energy level decreases). When people are in that state we encourage them with ‘genki dashite!’ (cheer up!). When people pretend to be genki, we say such behaviour is ‘kara-genki’ (putting on a brave face). The word ‘kara’ means empty. Being genki is so important to life that we even have the idiomatic expression ’genki ga ichiban’ (health is most important). That is why Japanese greet each other with expressions such as ‘ogenki desuka’ (how are you?), or ‘dozo ogenki de’ (take care of yourself) indicating concern for each other’s health. hatsuratsu: full of life, cheerful and healthy Feeling concerned about one’s physical condition: Otsukare-sama When we use our bodies or brains too much and are in a state of physical and mental weakness, we call the condition ‘tsukareta’ (tired) ‘kutabireta’ (exhausted) or ‘kutakuta da” (dead tired). The expression ‘otsukare-sama’ or ‘otsukare-sama-deshita’ is an idiom we use at the end of a day full of work or study when we are ready to go home. When we are so tired that we can’t move any more we call the condition ‘bateru’ (done in). With the approach of every summer, methods to combat ‘natsubate’ or summer fatigue, caused by extreme heat, become topical. People who are in the prime of their life would like very much to sit down in a commuter train or bus too. Perhaps Japan is just a tiring society. In recent years the country and the world have been rocked by the phenomenon of ‘Karooshi’ or people who work until they die of exhaustion. This term is now understood worldwide. Mental health is important: Illness derives from the psyche In Japan there is the following saying: Yamai wa ki kara (yamai means illness). This means that if ‘ki’ or the psyche (working of the mind or heart) is out of sorts and energy levels are down, it is easy to become sick. It is thought htat when people feel psychologically let down or brood over something, it is easy to catch cold or get hurt. Thatis why Japanese often say ‘ki o tsukete’ (be careful) or ‘ki ni shinaide’ (don’t worry about it). Since it is thought that people who are keyed up don’t get sick, people who miss work because of illness are actually scolded with having slacked off, ‘ki ga tarunde iru’. Psychological illness was thought in ancient times to be the result of possession by the spirit of foxes or other animals called ‘tsukimono (evil spirits). In such cases, ceremonies called ‘oharai’ were often held to ask the gods to exorcise the spirits. Watch out for Taboos! Omimai or inquiring after someone’s health Visiting some one who is ill or hurt, or sending a condolence gift is called omimai. A condolence gift usually consists of flowers or fruit. If fruit, the gift is an expensive delicacy that people rarely get a chance to eat. If flowers, potted plants are avoided because a plant with roots has meaning of ‘nezuku’ (taking root), also bringing to mind the word ‘netsuku’ (bedridden),a bad omen. For a similar reason, the hospital room numbers 4 and 9 are often missing because four (‘shi’ in Japanese) means death, while nine or ‘ku’ is associated with suffering. When the patient is released from the hospital and returns to work, he/she gives out a ‘kaiki-iwai’ gift to those who came to visit or gave a condolence gift when the person was incapacitated. The word ‘mimai’ can also be used for visits to people who have suffered from natural catastrophes such as fires. “mimai’ is also done to encourage candidates in elections, actors or anyone who is in a state of stress. This type of inquire is called ‘jinchu-mimai’. engi ga warui: to seem as if something bad will happen. Plugging along diligently, preventing illness: How to stay healthy Everyone wants to stay healthy. Most Japanese gargle and wash their hands every day when they get home as a way to prevent illness. Radio calisthenics have also caught on widely among Japanese. These exercises, in which calisthenics are done in sync with music and directives over the radio, has a history of over eighty years. Individuals and groups do the exercises at 6:30am when the radio program is broadcast; schools and some workplaces often use recordings or CD to follow these exercises regimen. Compared to Westerners, Japanese are sensitive to stiff shoulders, necks and lower backs. They often use hot baths or hot springs to relax their muscles through pounding or kneading is called ‘anma’ (massage). Sometimes burning moxa on their skin or acupuncture therapy is also used. Mubyo-sokusai: preventing illness and staying healthy It’s great to live long! Life expectancy Like most people throughout the world, Japanese believe firmly that life is granted from heaven. When a death occurs unexpectedly, it is called ‘inochi o otosu’ (lose one’s life). When someone escapes danger, it is called ‘inochibiroi o shita’ (escape with one’s life). A person’s lifespan is called life expedtancy or jumyo; to live a long life is called ‘choju’. Today population aging and it sconcomitant adverse effects is a problem, but from ancient times people in Japna have celebrated certain watershed ages. The age of sixty is called ‘kanreki’; seventy ’koki’; seventy-seven ‘kiju’; and eighty-eight ‘beiju’: each one has its own special name. When someone who has lived a long life passes away, it is said that the person lived out his or her allocated life span (‘tenju o matto shita’). Such funerals are held with a feeling of celebration. Rogai: a state in which leaders in industry and the political world are aging, among other adverse effects. Tenju o matto sshita: to live to the fullest the life granted by heaven.