Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice

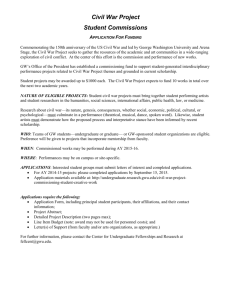

advertisement