Epistemology Model Answer

advertisement

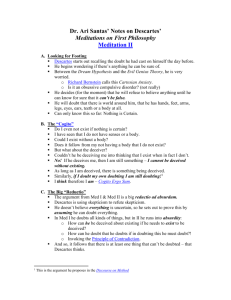

Epistemology Model Answer (a) Describe the arguments Descartes uses to arrive at a position of universal doubt in Meditation One. 10 KU 6 AE 5 9 KU AE (b) How effective are Descartes’ sceptical arguments in Meditation One? (c) Critically evaluate the claim that the cogito is beyond doubt. (30) a) In meditation one, Descartes contemplates the various sources of falsehoods in his life and attempts to show that we can, in fact, not trust any of our knowledge at all – a position called ‘universal doubt’, in which everything can be pulled into question. Descartes starts by considering knowledge gained from ‘authorities’ – the church, teachers etc. It is very clear that this knowledge can be doubted, because to hold it to be true, we simply have to put faith in these institutions. Next, he thinks about his sensory experience. Again, this can be doubted, since it is clear that our senses sometimes deceive us – in the case of optical illusions, or where the thing that we are observing is very small or far away. Descartes does maintain, however, that sensory experience is still quite sturdy, and he contemplates that because he is not insane, he feels that he can, by and large, trust this sort of knowledge. This is cast into further doubt with the ‘dream argument’, however. Descartes realises that when he is dreaming, he often imagines that he is sensing real objects, and is rarely aware, in these instances, that he is dreaming. The meditator considers, however, that even though his current sensory experience could be a dream, even dream images are drawn from our waking experience, much like paintings. When a painter creates an imaginary being, like a mermaid, the composite parts are drawn from real things - women and fish. In fact, even when a painter creates something entirely new, at least the colours are drawn from experience. At this point, Descartes concludes that even though he can doubt composite things, he cannot doubt the simple and universal parts from which they are constructed, like our rational, a priori understanding of arithmetic and geometry. On further reflection, however, Descartes realises that even these simple things could be wrong. Perhaps there is an evil demon whose sole purpose is to mislead him, and who sends incorrect sensory information – indeed, the entire world around us could have been created by the evil demon to deceive us. Descartes does not suggest that this is actually true, but he plants the doubt – how do we know that there is not an evil demon, or that we are not dreaming? b) Descartes’ attempt to arrive at universal doubt is reasonably successful. His reasoning to explain why it is impossible to trust our senses appears to be logical, and he makes good use of the evil demon argument to imply that our senses could be deceived. Descartes only needs the first meditation to introduce the possibility that our knowledge might be wrong, and it seems that he does this quite successfully. It could be argued that Descartes does not successfully arrive at a position of universal doubt, however, and there are a number of reasons for this. Descartes never doubts his own logic, memory, or his use of language. This makes it easier for him to rely on logic later in the meditations, but he has given no evidence as to why logic should be beyond all doubt when our senses can not be trusted. Whilst it is true that our senses can sometimes be deceived – with optical illusions and so forth – it may be possible to corroborate the reliability of the senses with the experience of others, or scientific instruments etc, and so it could be argued that completely denying the senses is not necessary. In the ‘dream argument’, Descartes posits that because you don’t always know you are dreaming when you are asleep, we may also never be sure that we are awake when we are awake. There is no evidence for this, however, and his argument is asymmetric – just because something is true when we are asleep does not mean the same will be true when we are awake. This is bad logic. Finally, there are a number of problems with the evil demon argument. To suggest that sometimes we are being deceived raises a number of problems, because it raises the possibility that we are being deceived all the time. If this 2 is the case, all knowledge would be up for doubt, even knowledged gained through reason (a priori knowledge). It is possible that the only reason 2+2=4 is because we have been deceived to believe this to be the case. c) ‘The Cogito’ refers to the assertion made by Réné Descartes in the second meditation that ‘cogito ergo sum’ or ‘I think therefore I am’. Descartes has shown in the first meditation that he doubts the sources of knowledge, and yet for him to have these doubts – for him to have the ability to doubt – he must exist. He goes on to think about the nature of this ‘I’ that exists. Originally, Descartes believed that he had a soul and a body, but both of these things had been cast into doubt in meditation one. He cannot doubt that he thinks, however, therefore the ‘I’ that exists must be a thinking thing. ‘I’ only exist as long as ‘I’ am thinking. Descartes believed that he was a rationalist, that is to say, only a priori knowledge gained through reason should be trusted. It could be argued that the cogito fails here, because the assertion that ‘all thinking things exist’ is based on Descartes’ knowledge and understanding of the world around him, and on his observation of ‘thinking things’, and so comes from a posteriori knowledge. Descartes did not intend for the cogito to be a piece of deductive reasoning, however. What this means is that Descartes did not intend for the argument to be: 1) Things that think exist, 2) I think, therefore 3) I exist. Instead, he wanted ‘cogito ergo sum’ to be taken as a whole or as a ‘self-authenticating principle’. It seems like common sense, using one’s intuition, that when one is thinking, one must exist. This is a strength of the cogito because it is true that we believe ourselves to exist using our own intuition. This still does not place the cogito entirely beyond doubt, however. Just because ‘thoughts’ definitely exist does not necessarily mean that ‘the thinker’ definitely exists. If Descartes had written ‘there is thinking going on, therefore there are thoughts’, the cogito may have logically made more sense, but in its current formulation, we could argue that merely thinking does not guarantee that ‘I’ exist, and therefore the cogito is not beyond all doubt. 3