The Method – Analysis and Criticisms

advertisement

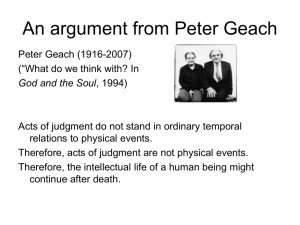

687319270 The Method – Analysis and Criticisms Certainty Is knowing something the same things as being certain that it is true? It does not seem so. If not, is Descartes setting himself too tough a challenge? Knowing and being certain seem to be different for the following reason. If I know p, I have sufficient justification for believing p to be true. For example, I know it is Wednesday because I have the evidence of the newspapers and the radio and the fact that my students and colleagues are behaving as if it were Wednesday. This evidence doesn’t rule out the possibility that I am the victim of some extremely complex hoax. But this remote possibility cannot undermine my ability to know. For we can always think of weird possibilities – dreaming and demons – that would undermine what I think to be true and this would mean that we don’t know anything. This seems absurd.1 If Descartes decided to look for knowledge and not certainty, he would have needed a criterion of knowledge. What would he use? Justified true belief? He would then have been faced with the problem of finding out just how much justification you need for knowledge. This is not easy to decide. I know that it is Wednesday even though my evidence and hence justification isn’t powerful enough to rule out the possibility of a hoax. Can I measure how much justification I have here? The advantage of looking for certainty is that you set yourself a clearer, if tougher, goal. If p is certain, then it rules out all possibilities that it might be false. Of course, Descartes could find that nothing is certain. If so, he would have to search for something weaker, such as knowledge. Doubt The key question now is: how do I tell whether something is certain? Descartes’ criterion is: can I find any reason to doubt it? But this is problematic for a number of reasons. First, who is to say that when I find reasons to doubt something that I am right? Suppose I am someone who doubts that Pythagoras’ theorem is true of all right-angled triangles. I doubt but my doubts are misguided. Second, who is to say that when I find that I cannot doubt something that I am right? Suppose I am someone who simply cannot make sense of the idea that the Earth is a sphere and not flat. Of course, one obvious way to check whether I’m right is to ask someone else. Philosophy and science are best done co-operatively. But since Descartes has committed himself to doubting that physical bodies – hence, human beings – exist, he cannot do this. Descartes says that we cannot doubt anything we “clearly and distinctly perceive”. If I have a clear idea, it is “present and open to the mind”. I can see it clearly in my mind’s eye. A distinct idea is one that contains nothing other than that which is clear. All of the idea can be seen clearly in my mind’s eye. It is therefore simple enough for me to “get my mind around”. The problem with this is that Descartes seems to be saying that we can’t doubt and hence know for certain things that strike us as clearly true. But, once again, many things strike people as clearly true that we know aren’t. Some people cannot entertain the idea that there might not be a God or that the Earth might not be flat. Page 1 of 2 687319270 The Contradiction Test When Descartes establishes his first certainty – the cogito – we can see that more is at work. He sees that he exists clearly and distinctly as a result of having used doubt, dreaming and demons to challenge his beliefs. This enables us to say the following. Descartes could doubt that he had a body because he thought up a way to make sense of the idea that he hasn’t a body. It is not contradictory to suppose he hasn’t a body. It is contradictory to suppose he does not exist when he thinks. Thoughts require a thinker. If the thought, “I do not exist” is true, there is no thinker. But we’ve just said that thoughts require a thinker and so we have a contradiction. We might therefore suggest the following test to see whether something can really be doubted. (TEST) I cannot doubt that p if attempting to do so leads me to a contradiction For example, I cannot doubt that 2 + 2 = 4. If I try thinking that 2+2=5, I can derive a contradiction. If 2+2=5 and I take 2 from both sides, I have 2=3. But 2 cannot be identical to 3 as it is only identical to 2! But there are still problems. First, I might be unable to determine whether doubting that p leads to a contradiction. Is it contradictory to suppose that space is infinite? It is not clear. Second, I can still make mistakes. Suppose someone says: “I cannot doubt that God exists, as I understand God to be something that necessarily exists.” But this is not a good proof that God exists. Someone might disagree with me over the nature of God. Problems With Scepticism The criticisms so far target the idea of looking for certainty via doubt. There is of course the question of whether Descartes is right to say that we could be dreaming or whether the Demon could fool us so completely. Descartes argued that the Demon could not fool us about our own existence as thinking things. Descartes then went on to say that we could have knowledge about the external world because of God’s existence and benevolence. Many people think Descartes’ proof does not work. In order to defeat the Dreaming and Demon hypotheses, we need to do something else. Philosophers have offered many arguments against the idea that we cannot tell whether we are dreaming and against the idea that we cannot tell whether we are being fooled by the Demon (or, equivalent, that we are in the Matrix). We shall look at these things separately. 1 A more sophisticated analysis of the problem is the following. Whether someone knows or not depends on the context. I am in an office with lots of plants. I know that there is a plant before me. Suppose I now go to an office where all the plants bar one are fake plants made out of plastic, this being some kind of art project. They are indistinguishable from real plants by sight alone. Quite by chance, I look at the one real plant. Do I know that I it is a plant? In this context, we might say that I don’t. I am lucky to be looking at the real plant. I could have easily been looking at a fake plant and have had a false belief. In sum, whether we know or not can depend on whether context: whether I could have easily been wrong in the context. Ordinarily, I would say that I know that it is Wednesday. The context is normal. The possibility of being the victim of a hoax is not relevant. But by considering it, I make it relevant. Hence, it exerts an effect. Page 2 of 2