Government of Nepal - Global Environment Facility

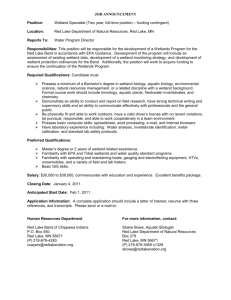

advertisement