"Not Marriage at All, but Simple Harlotry": The Companionate

Marriage Controversy

Rebecca L. Davis

Only a few family members heard the Unitarian minister proclaim them husband and wife in Girard,

1

Kansas, on November 22, 1927. But by the following evening, newspapers from New York to Los Angeles

reported that Josephine Haldeman-Julius, aged eighteen, had wed Aubrey Clay Roselle, aged twenty, a

student at the University of Kansas, in a secret ceremony at her parents' home, held a few days ahead of

schedule in a futile bid for privacy. Readers learned that neither God's name nor even a reference to God's

authority had passed the lips of the minister who officiated at the ceremony. Josephine and Aubrey had not

exchanged the traditional Christian wedding vows, nor had the minister asked Aubrey to "endow the

woman with his worldly goods."1 Instead, Josephine and Aubrey swore their commitment to one another as

partners in a "companionate marriage." As they described it, companionate marriage enabled them to marry

(and thus have a socially sanctioned sexual relationship) while still too young to support themselves

financially. In principle, if not yet by law, Josephine and Aubrey's companionate marriage permitted

divorce without alimony at the two-year mark, assuming no children had been born in the interim.

Josephine planned to continue living with her parents in Girard until she finished high school, after which

she hoped to become a professional dancer. Aubrey would return to Lawrence, Kansas, to complete his

degree. Though hardly mentioned in the press, the use of contraceptives enabled both husband and wife to

pursue their educations and careers while still conforming to moral precepts and social conventions that

limited sexual intercourse to marriage. "It seems almost too beautiful to be true to me," Josephine told the

reporters who had descended on her parents' home.2 Their companionate union epitomized what historians

have described as marriage's early twentieth-century transformation from a patriarchal, procreative

institution into a relationship premised on equal sexual desires and mutual emotional fulfillment. But if it

reflected the norm, why did Josephine and Aubrey's wedding become a national media event? What was

companionate marriage?

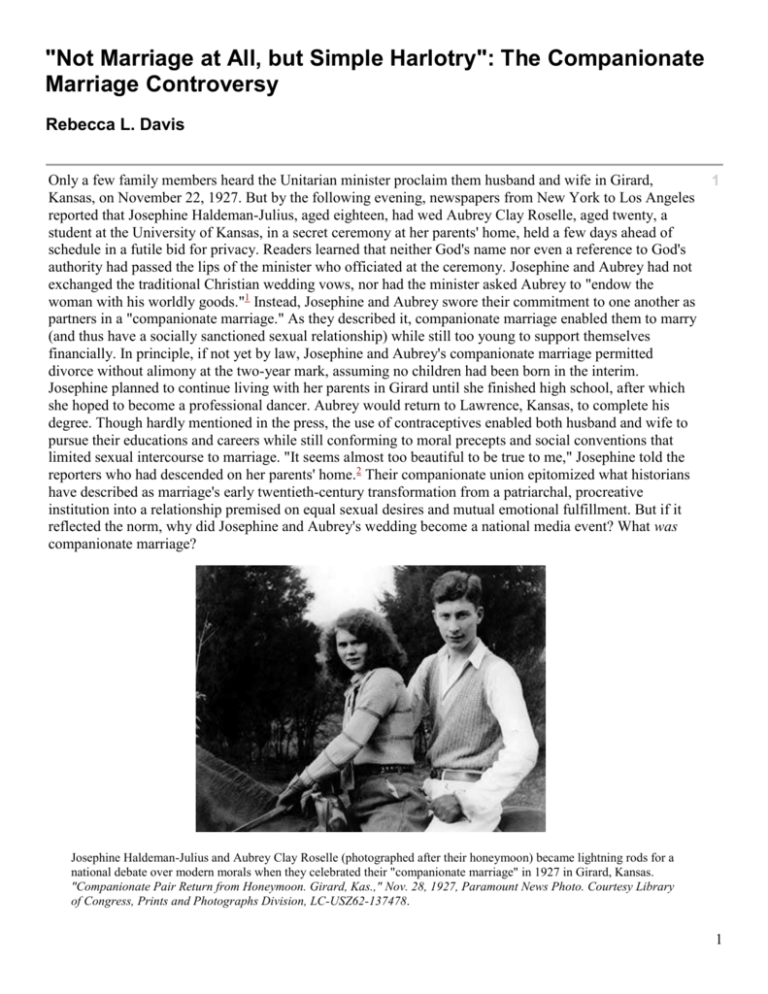

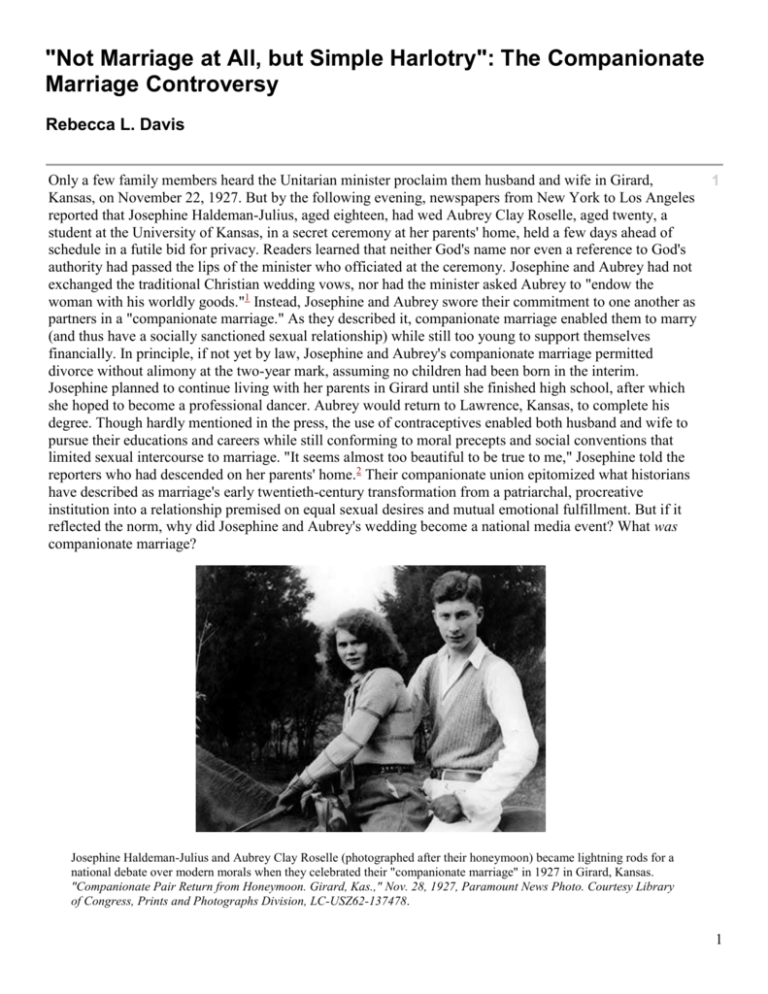

Josephine Haldeman-Julius and Aubrey Clay Roselle (photographed after their honeymoon) became lightning rods for a

national debate over modern morals when they celebrated their "companionate marriage" in 1927 in Girard, Kansas.

"Companionate Pair Return from Honeymoon. Girard, Kas.," Nov. 28, 1927, Paramount News Photo. Courtesy Library

of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-137478.

1

The definition of companionate marriage has engendered confusion since its introduction into the

2

American vernacular at the height of the Jazz Age. Sociologists first coined the phrase "companionate

marriage" in the 1920s to describe a transformation in the social and economic functions of marriage for

middle-class, and predominantly white, American families. By the early 1920s, norms of middle-class

social behavior were in flux. In place of the nineteenth-century ideal of white women's "passionlessness,"

American moderns acknowledged the naturalness of sexual desire among so-called respectable women.

Rates of premarital sex, divorce, and women's white-collar employment had all risen over the previous two

generations. The birth control movement's early successes also enabled women with access to physicians to

obtain increasingly reliable forms of contraception. Particularly after women won the franchise in 1920,

marriage no longer created a legally or politically cohesive unit: married women possessed unprecedented

control over their personal property, employment, and bodies. As sociologists explained, those changes in

women's status and in reproduction had helped develop the modern idea of companionate marriage. Such

marriages embraced democratic family organization, produced fewer children, and prioritized couples'

mutual emotional and sexual needs. As many historians have made clear, however, the idealization of

heterosexual matrimony in the name of companionate marriage undermined radicals' efforts to liberate

sexuality from marriage and anathematized homosexuality.3

Most Americans learned about companionate marriage, not from social scientists, but from Judge Ben

3

B. Lindsey of Colorado (1869–1943), a nationally famous reformer and something of a publicity hound.

Lindsey had made his name as a Progressive Era champion of the new juvenile court system; he

inaugurated such a court in Denver and presided over it for nearly thirty years. In the mid-1920s he began

to teach the public about companionate marriage through radio addresses, magazine articles, books, and

lectures. More dramatic than systematic, Lindsey offered an occasionally confusing, but always

impassioned, defense of companionate marriage as the key to sexual morality. Unlike sociologists, who

described long-term trends in Americans' marital behaviors, Lindsey took a prescriptive approach. He

advocated providing couples with birth control and access to easy divorce, so that marriage might become a

modern institution, free from moral hypocrisy. Despite this zealous commitment to liberating sexuality and

reforming how couples could enter and exit marriages, Lindsey ignored how companionate marriage might

affect gender roles. Companionate marriage would allow women as well as men to express themselves fully

as sexual beings, but it said nothing about equality of status or work. Lindsey's analytical oversight left him

open to attack by critics who readily analogized companionate marriage to a crass system of sexual

exchange.4

Lindsey pushed his critics to envision a radically egalitarian marital relationship—a relationship that, to 4

their minds, would be no kind of marriage at all. His reforms threatened to put married women in

possession of their sexuality; easy divorce would enable them to enter and exit a series of relationships at

will. In the conservative political climate of the 1920s, Lindsey's critics associated that marital ideal with

atheism, prostitution, and "Bolshevism." They equated heterosexual monogamy, sanctified by religion, with

American democracy and capitalism. (That Josephine's father, E. Haldeman-Julius, had attained notoriety

as a socialist, atheist, and publisher of pocket-sized editions of works by radical authors only reinforced

those contrasts for the general public.)5 Lindsey's proposals seemed to threaten the heterosexual status quo

by loosening social and symbolic bonds between women's sexuality and monogamous marriage. This

gender conservatism among both theological traditionalists and theological modernists, as well as among

social scientists, cemented the opposition to companionate marriage. Theological traditionalists, whose

insistence on both religious and gender orthodoxy led them to oppose birth control and divorce reform,

rejected most of what Lindsey proposed. Even many theological modernists, who supported birth control

and divorce reform in their attempts to harmonize religion and modernity, found reasons to criticize

Lindsey's platform, despite their agreement with most of its planks. Critics and proponents of companionate

marriage alike worried almost exclusively about how it would affect white—and usually middle-class—

women. Thus racial biases also structured resistance to altering reproductive patterns. For individuals who

viewed traditional marriage as the fundamental building block of Judeo-Christian democratic capitalism,

companionate marriage presaged the dismantling of the reigning political order, one marriage at a time.

2

The long-forgotten clashes between Lindsey and his critics reveal the limitations of using companionate 5

marriage to describe gender relations during the 1920s. The term's muddled origins and significance

complicate the task of connecting it with either actual or idealized behaviors. Historians have used the

phrase to capture a modern emphasis on mutuality and intense emotional bonds within marriage. As the

economic prosperity of the 1920s ended and the Great Depression began, however, companionate marriage

came to be seen as not only dangerous but ridiculous, the latter thanks in no small measure to Lindsey's

public confrontations with respected religious leaders. Although birth control gained public acceptance

(and, privately, its use increased) during the 1930s, the popularity of companionate marriage declined.

Lindsey's failed reform agenda—modest when contrasted to that of the earlier free lovers with whom he

was falsely compared—signaled the end of serious proposals to restructure marriage in the United States

until the late 1960s. Instead, clergy partnered with social scientists, several of whom explicitly opposed

Lindsey's brand of companionate marriage, to teach Americans how to adjust to existing patterns of

heterosexual monogamy. The controversy over companionate marriage, molded by conservative politics

and religious discourses of sexual virtue, ultimately proved more significant than companionate marriage

itself in shaping modern ideals of moral, heterosexual matrimony.

Defining Companionate Marriage

Social scientists coined the term "companionate marriage" in 1924 to describe a union in which spouses

6

intentionally controlled their fertility and embraced a modern egalitarian ideal. Young companionates

rejected patriarchal family models and instead envisioned marriage as an equal partnership between

spouses, bound by romantic rather than economic obligations, and committed to the fulfillment of each

individual's emotional and sexual needs. Sociologists writing in the Journal of Social Hygiene, the

professional periodical of the eugenically oriented American Social Hygiene Association in New York

City, defined companionate marriage as the expression of an antipatriarchal impulse among white, middleclass American couples. Companionate marriages resulted from what those sociologists described as the

family's loss of its economic and social functions. Instead, modern marriage provided emotional comfort

and romantic love, while contraceptives attenuated the links between marriage and reproduction. One

author in the Journal of Social Hygiene defined a companionate arrangement as "the state of lawful

wedlock, entered into solely for companionship, and not contributing children to society." He contrasted it

to the family, "in its true historical sense, as the institution for regulating reproduction, early education,

property inheritance, and some other things." Another author argued that it was in the government's interest

to recognize those distinctions and to treat "companion marriages" differently. By enabling governments to

assess a couple's "fitness" before they had children, the author explained, companionate marriages offered

the best chances for long-term eugenic health and reduced the number of children who would become

public charges. Sociologists therefore defined companionate marriage as a consequence of shifting social

relations and as a pragmatic response to eugenic concerns.6

Historians' accounts of companionate marriage have largely adhered to that sociological model. While

7

the family historians Steven Mintz and Susan Kellogg apply the term to marriage in the entire period from

1900 to 1930 and historians of the nineteenth-century family describe the rise of a companionate, or

romantic, ideal of "a union based on a partnership of friends and equals," most historians use the phrase

"companionate marriage" to describe marital ideals first championed by radicals in the 1910s and adopted

by the middle classes in the 1920s. Historians note, for example, that companionate marriages implied

mutual emotional and erotic fulfillment; companionate spouses would derive their fullest intimate

satisfactions from one another. In the historian Nancy F. Cott's words, companionate marriages transformed

the home into "a specialized site for emotional intimacy." Such marriages also produced fewer children, as

more Americans procured effective contraceptives from their doctors or other sources. Historians have

evaluated companionate marriage critically, demonstrating how the companionate ideal privileged

heterosexual intimacy over same-sex friendship and pressured women to find personal gratification, social

status, sexual pleasure, and financial stability exclusively in their marriages. Paula S. Fass's 1977 discussion

3

of youth culture during the 1920s comes closest to capturing Lindsey's prescriptive formulation. She

nevertheless takes Lindsey at his word about his proposal's conformity to popular norms of virtue and

chastity.7

Rather than celebrating an emergent norm, however, Lindsey was calling for change in a culture he

8

considered crippled by hypocrisy and shame. He first tackled questions of sexual morality in The Revolt of

Modern Youth (1925), which recounted his sympathy for the young people, especially the girls, who landed

in his Juvenile and Family Court. The book described how he gallantly tried to salvage their self-esteem

and guide them toward rectitude, but its underlying message was the failure of "puritanical" traditions.

Lindsey's attacks on puritan ideals relied on stereotypes of a prudish Victorian bourgeoisie, immersed in

self-righteous claims of Christian virtue. Lindsey proposed to base marriage and family life on "modern"

standards of mutual sexual desire, contraceptive use, and companionship instead. He focused his sense of

pathos on pregnant adolescent girls. They had not sinned, he insisted, but were the victims of parents and

schools that had inadequately prepared them for life's inevitable sexual temptations. Problems with

premarital sex arose, not from human depravity, but from the limitations set by accepted codes of marital

behavior. By removing the stigma from sexual pleasure and legalizing birth control, Americans might yet

rescue marriage from its declension. Lindsey's plan to save American youth thus hinged on cultural and

legal reformulations of marital obligations.8

Much of what Lindsey proposed echoed the ideas advanced in prior decades by free lovers, sex radicals, 9

and reformers. In the nineteenth century, ideas for reforming marriage emanated from temperance, suffrage,

abolitionist, Spiritualist, anarchist, and socialist camps. According to free-love principles, married women

possessed the inherent right to refuse intercourse with their husbands when they did not desire it and to

leave husbands they no longer loved. They would be "free" to follow their hearts, rather than submitting to

sex out of duty or obligation. Women's rights crusaders from the 1840s through the 1870s argued for liberal

divorce laws that would allow individuals to loosen the bonds of unloving marriages. By the early twentieth

century, free love assumed a more anarchic form among bohemian sex radicals and their followers, many

of whom lived out their rhetoric about the oppressive nature of marital monogamy. Free lovers supported

the birth control movement, premarital and extramarital sex, and, at least in principle, women's full

equality. Only a very few American radicals, such as the anarchist Emma Goldman and the labor activist

and bohemian rebel Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, suggested abolishing marriage altogether. By the 1920s,

however, many former free lovers had tempered their radicalism by describing monogamous marriage as

the culmination of heterosexual love. Instead of reforming marriage to improve sex, they would reform sex

to improve marriage. The companionate marriage controversy that encircled Ben Lindsey arose at a

moment when more radical ideas about dismantling bourgeois marriage were giving way to

accommodations to marital traditions.9

Lindsey's goal was quixotic—and even self-contradictory—from the outset: to endorse sexual

10

modernity by enlarging the circle of marital morality. He explained himself in a series of articles entitled

"The Moral Revolt," published in Red Book Magazine between October 1926 and April 1927; he later

compiled and expanded those articles, with the help of coauthor Wainwright Evans, in The Companionate

Marriage. In the articles he derided the hypocrisy of "puritan" ideas, especially female chastity (which,

Lindsey emphasized, meant that men owned their wives as property). Just as Prohibition had made drinking

an obsession, so puritanism produced a sex-crazed society. Educated, "sophisticated" couples already

practiced a form of companionate marriage by using their knowledge of "scientific contraception" and their

access to lawyers who could help them negotiate "collusive divorces." Lindsey peppered his magazine

articles and The Companionate Marriage with stories to illustrate the extent of changing sexual mores.

Well-heeled couples agreed to remain married while enjoying extramarital affairs, husbands divorced their

sexually shy wives, and prominent citizens' teenage daughters had premarital escapades. He blamed rigid

moralism, not individual immorality, for the frustrations of couples struggling to reconcile their romantic

longings with a one-size-fits-all marriage system. In place of that unforgiving orthodoxy, Lindsey offered a

bold but frequently inconsistent campaign for marriage reform.10

Lindsey first used the term "companionate marriage" in print in the February 1927 issue of Red Book

11

4

Magazine. In that article, he proposed a second "kind" of marriage, called companionate marriage, that

would allow young adults a sanctioned form of sexual expression without committing them to a lifetime

together. Young couples who could demonstrate to a magistrate "that they were physically, mentally—and

economically—fit" would be allowed to solemnize a marriage contract whose "purpose was simply to

enjoy the full companionship which such living would make possible." At the beginning of The

Companionate Marriage, Lindsey emphasized changes to existing laws, rather than complete legal

innovations: "Companionate Marriage is legal marriage, with legalized Birth Control, and with the right to

divorce by mutual consent for childless couples, usually without payment of alimony." To his coauthor

Evans, however, Lindsey privately acknowledged the fine line between revolutionizing marriage and

accommodating social trends, even as he perhaps inadvertently contradicted himself. One chapter draft, he

wrote to Evans, "assumes that we are proposing some NEW KIND of marriage. We can get the laugh on

the other fellow by showing that we are only discussing marriage as it actually is." Nonetheless, confusion

persisted about whether Lindsey's plan encompassed social revolution or legal accommodation to current

mores, and many of his admirers wrote to him for clarification. Lindsey coyly acknowledged this

bewilderment in an article in the magazine Outlook, titled "What Do You Think It Is?"11

Many people, it turned out, thought companionate marriage was trial marriage, an idea popularized by 12

the British sexologist Havelock Ellis in the late nineteenth century. Ellis had argued that, although society

had an obligation to forge legal arrangements between parents, no comparable state interest could justify

compelling childless lovers to marry. (The radical British philosopher Bertrand Russell made similar

arguments in the 1920s.) Thus Ellis advocated "trial marriage," an experimental, nonbinding relationship.

He insisted that both trial and legal marriage should terminate when sexual and emotional attraction ended,

and he thought divorce should be granted upon either party's request. The state would intervene only to

ensure that children received adequate support.12 Critics from across the political spectrum found little in

Lindsey's proposal to distinguish it from trial marriage or to free it from associations with sexual

promiscuity. Scores of newspaper and magazine articles cited ministers, social scientists, and cultural

observers who insisted they had seen past Lindsey's facade of respectability to his true aim of fomenting

sexual immorality. These repeated conflations of companionate and trial marriage frustrated Lindsey's loyal

readers, one of whom wrote to him for clarification. Having read Lindsey's articles in Redbook and heard

him deliver lectures on companionate marriage, she found little resemblance between his proposals and trial

marriage. But others' accusations made even this committed acolyte falter. Seeking reassurances, she

enclosed a clipping from her local newspaper that described a minister's charges against Lindsey. "I am

unwilling to condemn anybody unheard in his own defense. And, either I misconstrued your article—or this

minister's harangue is hearsay evidence." The specter of trial marriage haunted Lindsey.13

Associations between companionate and trial marriage persisted despite Lindsey's efforts to position

13

companionate marriage as something far less radical. He confessed that "technically" trial and

companionate marriage were similar: both featured birth control, divorce by mutual consent for childless

couples, and a recognition that it was never certain a marriage would "turn out to be a permanent success."

The distinction lay in the "emphasis" of trial as compared to companionate marriage. Men and women

contracted companionate marriages, Lindsey explained, expecting that their marriages would succeed,

though they recognized the "remote" chance that they would fail. When a couple contracted a trial

marriage, in contrast, they sought, not a permanent relationship, but "a temporary sex episode" similar to an

"unmarried union" or free love. Lindsey's attempts to distance companionate marriage from trial marriage

and its radical connotations failed. The Companionate Marriage's dust jacket endorsements from Havelock

Ellis and the author Floyd Dell identified the book as a product of the modernist, bohemian Left. That a few

prominent atheists, including the critic H. L. Mencken, the author H. G. Wells, and Bertrand Russell, also

became outspoken admirers of Lindsey's ideas did not help matters.14

Lindsey's assertions that companionate marriage could have eugenic value meanwhile conformed to

14

common ideas about how social science could promote race betterment. Without discussing race per se,

Lindsey recapitulated popular theories about how hereditary traits affected character, intelligence, and civic

responsibility. In the mid-1920s eugenics reflected a middle-class ethos of scientific management and race

5

betterment.15 As was popular in his day, Lindsey assumed that a better class of people existed and that

society should remove impediments to their marrying and reproducing. As Lindsey had explained in The

Revolt of Modern Youth, contemporary marriage customs, by penalizing the victims of a single indiscretion,

often discouraged young people with "desirable physical and mental qualities to transmit" from procreating.

Better that men and women between the ages of seventeen and thirty-five should marry, he noted in the

summer of 1927, "even though it might mean an increase in divorces and separations." Lindsey conversely

bemoaned the number of births among intellectually inferior Americans. In The Companionate Marriage,

he even forecast the government's eventual involvement in screening couples for their parental

qualifications and subsidizing couples "when the financial means are limited, but the stock is sound."

Lindsey insisted that companionate marriage would carry eugenic benefits by encouraging more of the

racially superior and educationally advanced young people to chose marriage and parenthood.16

By summer 1927, Americans who read newspapers and middlebrow periodicals, attended lectures, or 15

listened to the radio had ample opportunities to assess Lindsey's companionate marriage program for

themselves. Members of the general public, clergy, and social scientists issued responses to his proposals

that ranged from hearty praise to damning condemnation. Through it all, Lindsey insisted that

companionate marriage offered the only modern way forward for American families, in tune with scientific

rationalism rather than outmoded religious teachings. This outward antagonism toward religion, combined

with companionate marriage's implications for household governance and divorce, allowed his critics to tie

companionate marriage to dangerous political movements and the corruption of female virtue.

The Bull Mouse Takes on Modern Marriage

Lindsey had made a career of championing underdogs and defending truth over hypocrisy, though his

16

battles had been hard won. Vacillating religious allegiances punctuated Lindsey's early years. His parents'

denominational differences (his father was an Episcopalian, his mother a Methodist) came into starker relief

when Lindsey was in his early teens and his father converted the family to Catholicism. The family

relocated from rural Tennessee to Denver. In keeping with their father's new faith, Lindsey and his younger

brother studied at the University of Notre Dame. The family's diminishing finances drew the boys back to

Tennessee to live with their maternal grandparents, who promptly enrolled their grandsons in Southwestern

Baptist University. Lindsey identified himself as a Christian throughout his life, but these denominational

peregrinations left an enduring antagonism to people who defended theological absolutes. After Lindsey's

father died a few years later, leaving his wife and three children impoverished, Lindsey returned to Denver

to support his mother and siblings, studying law at night. He became a lawyer only after numerous attempts

to pass the Colorado bar exam and despair so deep he attempted suicide. His break came in 1900, when he

was appointed to fill a midterm vacancy on Denver's district court. Lindsey fared well in elective office. In

1903 he formally established the Juvenile and Family Court of Denver, for which he became famous. He

implemented special trial procedures and sentencing guidelines for minors and advocated juvenile detention

centers and reformatories at a time when most underage offenders went to prison with adults. By taking

controversial but principled stands on labor rights, municipal corruption, and antiobscenity legislation, he

earned the respect of Progressive Era reformers and free speech advocates, as well as the ire of many

business, government, and racist groups, including the Ku Klux Klan.17

Lindsey hardly looked the part of the heroic crusader. Of medium height, slightly built, with a bald head 17

and a full moustache, he appeared more the gentle uncle than the scandalous radical. President Theodore

Roosevelt recalled that during the 1912 election campaign Lindsey's enemies had referred to the five-footfive, ninety-eight-pound judge as the "Bull Mouse." (Lindsey attributed his small stature to malnourishment

and stress during his adolescence.) Lindsey's reform campaigns, however, caught the public's attention.

When American Magazine polled its readers in 1914 for their choice of the "greatest living American,"

Lindsey tied for eighth place with Andrew Carnegie and the baseball-star-turned-evangelist Billy Sunday.18

The companionate marriage controversy tested Lindsey's popularity with the American public and with 18

his traditional allies. His Red Book Magazine articles, lectures, radio broadcasts, and, finally, the

6

publication of The Companionate Marriage generated a flurry of published and unpublished responses.

Lindsey received some adulation. After praising Lindsey for his bold ideas, dozens of people penned

detailed descriptions of their own romantic dilemmas, marital problems, and sexual anxieties. Many of

Lindsey's supporters from his decades-long career as a juvenile court judge, however, wrote to him in

disgust. The most damning critiques likened companionate marriage to Bolshevik Communism, atheism,

and prostitution.

Charges of Bolshevism bore symbolic weight in the 1920s. The postrevolutionary Russian government 19

had reformed the country's marriage and divorce laws and legalized contraceptives as part of its mission to

dismantle traditional bourgeois relationships. Between 1917 and 1926, the Russian government modified

marriage and divorce laws several times. Soviet citizens who wanted either to marry or to divorce needed

only to present themselves with witnesses before the appropriate bureau and pay a nominal fee, which

American newspapers reported as $0.20 for marriages and between $0.15 and $1.50 for divorces. The

American press stressed that Soviet law granted common-law marriages the same legal recognition as

marriages registered with government agencies. A writer for the North American Review concluded that the

registrations equated Russian marriages with free love.19

Analogies between companionate marriage and atheistic Bolshevism pervaded reactions to Lindsey's

20

call for companionate marriage. A Sunday evening broadcast on the Denver radio station koa on March 13,

1927, allowed Lindsey to explain his proposal to listeners in cities as disparate as Kokomo, Indiana, and La

Mesa, New Mexico. One woman responded to the broadcast by noting that she and her husband "were

incensed that such Bolshevistic propaganda should be broadcasted over the radio." Another koa listener

worried that Lindsey stood poised to "try to undermine the safety of our government" by seeking "to

destroy our most sacred institutions and customs." Many clergy similarly insisted that American

democracy, religious values, and monogamous, lifelong marriage were inextricably intertwined. A

Christian Church minister from Indiana warned that companionate marriage expressed a "distinct tendency

toward Bolshevism," was "anti-Christian," and would lead to "race suicide."20 Such individuals helped

popularize a rhetorical trope that asserted a nefarious alliance between free love and Bolshevism. While the

Bolshevik Revolution had indeed wrought significant changes in Russia's marriage and divorce laws,

charges that changing sexual practices might engender Communism owed more to fearful conjecture than

to political reality. Rarely explained, the cognitive leap from sexual behavior to political sympathies elided

intervening questions about individual citizens' relationships to their governments. How, exactly, did sexual

practices affect forms of governing, or vice versa? Such accusations buried assumptions about the gendered

nature of American democracy and capitalism within warnings about the dire consequences of Bolshevistic

practices.

A questionnaire about companionate marriage, distributed to Smith College's graduating class of 1924, 21

provided ammunition in 1927 for critics who wanted to portray companionate marriage as a Bolshevistic

threat to white middle- and upper-class women. The questionnaire, written and distributed by the chair of

Smith's sociology department, asked seniors whether they aspired to home, career, or both; whether they

wished to marry; and whether they sought "a companionate without marriage," "a companionate with

marriage," "marriage without children," or "marriage with children." A copy of that questionnaire, supplied

by a Smith student's mother, landed in the hands of the Massachusetts Public Interests League (MPIL), a

conservative women's organization that had shifted its focus from antisuffrage to anticommunism following

passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Combining Red Scare fears with what the historian Kim Nielsen

has described as their "discomfort with the consequences of large-scale women's education,"

representatives of the MPIL complained that the sociology professor and Smith's president inculcated

atheism and turpitude in the daughters of New England's elite by assigning books by Bertrand Russell and

encouraging students to challenge tradition. The MPIL's attack, launched in the summer of 1927 as

Lindsey's ideas were gaining widespread attention, sought to discredit companionate marriage by

portraying it as a threat to respectable women and as a manifestation, in one outraged MPIL woman's view,

of "Bolshevik and Anti-Christian" ideals. A similar questionnaire seeking students' views about

companionate marriage and premarital sex, circulated by a student at the University of Missouri, resulted in

7

the dismissal of two professors and an investigation by the American Association of University Professors

in 1929.21

Despite some parallels between Lindsey's companionate marriage and the legal changes afoot in the

22

Soviet Union, the comparison acted primarily as metaphor. Bolshevism denoted state-directed Communism

that "reduced" marriage to free love and obliterated the bourgeois husband's economic responsibility for his

wife and dependents. As a columnist for the Los Angeles Times explained in 1927, Lindsey's plan for "trial

marriage" constituted a "heresy unworthy of American civilization" because it would encourage

reproduction among divorce-prone and irresponsible "moral derelicts" and thus leave countless children

dependent upon state aid. This increased tax burden would diminish the quality of American citizenship,

the author continued; paying higher taxes to support dependent children abrogated the capitalist contract

between state and citizen to protect personal property: "The idea of trial marriage is a Communistic one, the

object being to make the rearing of children a duty of the state." When Lindsey reportedly told a Los

Angeles audience that he recommended "five-year marriage contracts," his critics labeled that idea another

kind of Bolshevist enterprise to undermine the family. Lindsey proposed his five-year plan a year before

Joseph Stalin announced his, but Lindsey's critics interpreted all his efforts to reform marital permanence as

evidence of his Communist, free-love leanings.22

One of Judge Ben B. Lindsey's fiercest opponents was William T.

Manning, the Episcopal bishop of New York, pictured here in October

1926. Hoping to hold back the course of modernity, Manning inveighed

against divorce, birth control, and premarital sex. Courtesy General

8

Theological Seminary, St. Mark's Library, William Manning Collection.

Attacks on Lindsey's "Bolshevist" ideas assumed a natural relationship between monogamous,

23

procreative marriage, Western civilization, and American democracy. As the Episcopal bishop of New

York, William T. Manning (1866–1949), explained, "The family is the most fundamental institution of

human life. Civilization depends upon the sanctity of the home. The life of our country depends upon this."

Manning warned that marriages terminated for "trivial" reasons, especially by people wishing to remarry,

presaged civil society's demise, citing the eighteenth-century historian Edward Gibbon's account of easy

divorce in the crumbling Roman republic as proof. Manning judged civilizations by their faithfulness to

monogamy, a practice that separated modern superiority from premodern "barbarism" and capped

evolutionary progress. For Manning, monogamous marriage forged a sacred chain, linking successive

generations to timeless values and humanity to its religious obligations. Marriage itself was not

evolutionary; it did not change to suit new social needs, but rather symbolized unchanging Christian truth.

Less doctrinally conservative religious leaders concurred about the damage companionate marriage might

cause. When the Reform rabbi Meyer Winkler of Temple Sinai in Los Angeles denounced companionate

marriage in 1927, he accused Lindsey of endangering "civilization," which "begins with marriage." These

religious leaders tied their opposition to companionate marriage to a defense of "civilization," a term loaded

with racial and gendered meanings. A "civilized" man would know how to channel primitive impulses into

socially acceptable behaviors. To these critics, companionate marriage offered a dangerous loosening of the

civilizing ties of lifelong, procreative unions.23

In defending civilization, Christian and Jewish leaders often likened companionate marriage to

24

prostitution and warned that the degradation of female sexuality would shake the foundations of human

society. Seizing the controversy as a conduit for their cultural authority, clergy deployed the rhetoric of

sexual purity—the ideal of chastity that Lindsey deplored. Bishop Manning declared that companionate

marriage was "not marriage at all, but simple harlotry." Similarly, the Rev. Dr. Caleb R. Stetson of Trinity

Episcopal Church in New York City charged that companionate marriage was "a new name for an old and

vicious thing." Stetson explicitly contrasted companionate marriage to Victorian sexual morals, which he

thought more accurately reflected Christian beliefs. The current generation desecrated a holy institution,

reducing sexual fidelity to "a social contract, to be broken at will." By equating companionate marriage

with prostitution, those ministers nostalgically invoked a middle-class nineteenth-century ethos of sexual

abstinence outside marriage and sexual continence within it. Though these ideals theoretically applied to

men and women, they helped perpetuate a sexual double standard that made allowances for male passions

while demanding female purity. Women's sexuality unmoored from that chaste, monogamous anchor

reeked of a licentiousness that only a prostitute would permit. The ministers did not extend the metaphor

(did husbands become procurers, if wives became prostitutes?), but they exposed fears about how women's

expanding social and sexual freedoms would change the institution of marriage.24

Members of the general public similarly accused Lindsey of sullying women's honor by disrupting

25

correlations between biological sex (male and female), gender roles (masculine and feminine), and sexual

appetites (innately aggressive and naturally latent). In a letter to Lindsey a writer identified only as Mrs.

Hays of Memphis, Tennessee, warned that his ideas trod dangerously close to condoning adultery and

permitting men to abandon their wives: "Woman's maintaining the human race has achieved the greatest

work in the world. She deserves the consideration and protection of a husband and father.... If you are not

for woman's protection and the home you are against them." Her letter portrayed men's sexuality as volatile

and dangerous, a threat that marriage would contain. Without marriage to restrain men's erotic energies,

untamed masculine sexuality would imperil women's honor and thus debase humanity. One self-proclaimed

defender of "traditional marriage" warned in McCall's that companionate marriage provided a "masculine

9

solution" to men's carnality without protecting "the young girl who has no such tempestuous urge." Echoing

the language of late nineteenth-century crusades against prostitution and "white slavery," others charged

that companionate marriage would "ruin" young women and lead to their degradation. "If companionate

marriage were to be accepted," one mother of three married daughters wrote to an advice column in the

Washington Post, "the girls would be the sufferers." More interested in marriage than boys were, girls

would "force" their boyfriends into companionate marriages, only to be jettisoned for other "temporary

mate[s]." If men possessed natural sexual desires far greater than women's, this mother argued, then

companionate marriage would facilitate men's promiscuity by condoning sexual liaisons. One of Lindsey's

correspondents worried about how companionate marriage would affect divorced women over the age of

forty-five, given men's tendency to look for younger mates. If laws changed but gender norms did not, how

would women fare?25

Some of Lindsey's readers, however, recognized that companionate marriage could promote women's 26

sexual emancipation by transforming customs and prejudices in tandem with legal change. Responding to

the Red Book articles, one single woman from San Jose wrote, "Women should be allowed the same rights

as men and should not be ostracized for the same thing that men have been doing through all the centuries."

Women frustrated by their own marital experiences seized on Lindsey's call for reform. A Houston wife

praised Lindsey for understanding the essential unfairness of marriage without recourse to divorce, which

she described as a conduit to heartache, a trap for women. Companionate marriage also provided feminists

a way to discuss obstacles to married women's educations and careers, and the importance of effective birth

control to women's social and economic advancement. The women's rights advocate Charlotte Perkins

Gilman praised Lindsey for offering a solution to unchecked population growth and for recognizing that

"for two people to live together as man and wife without love is gross immorality." Gilman's rhetoric

evoked the free-love reformers and women's rights advocates of the nineteenth century, for whom women's

ownership of their bodies remained a paramount concern. (Gilman's praise for population control attested to

her racially based eugenic biases; she sought greater rights particularly for white women.) Indeed, it would

not be until the late twentieth century that all states lifted their marital rape exemptions, relics of a legal

system that defined married women as their husbands' property.26

Political problems back home stalked Lindsey as he set off on a national radio and lecture tour to

27

promote The Companionate Marriage in the summer of 1927. His feuds with Denver's political

establishment and his anticorruption crusades had long antagonized members of all political parties, but his

censure of the Denver mayor's alliances with local Ku Klux Klan leaders nearly ended his judicial career.

The mayor and his allies charged that votes from the "Jewish precinct," a predominantly Jewish

neighborhood that had persistently supported Lindsey, had been tabulated falsely in the 1925 election, and

that Lindsey's opponent—endorsed by the Klan—should have ascended the juvenile court bench. Even

though the Klan candidate had since committed suicide, his widow brought suit against Lindsey for her

husband's lost wages from 1925 to the time of his death. The Colorado Supreme Court ruled in January

1927 that Lindsey's reelection to the juvenile court had been fraudulent. When the U.S. Supreme Court

declined to hear Lindsey's appeal that summer, it left Lindsey with no recourse. With characteristic

histrionics, Lindsey explained in his memoirs that "this was my Gethsemane!"27

Angry and defensive, Lindsey provoked critics of companionate marriage, challenging several of them 28

to debates. He seemed particularly thirsty for the blood of religious conservatives. Though guided by a

strong sense of Christian morality, Lindsey remained hostile to religious orthodoxy and dogma, perhaps in

reaction to the peripatetic religious education he received in adolescence. After Bishop Manning criticized

the Red Book articles, Lindsey threw down the gauntlet. Lindsey blamed the "illicit sex relationships and

the unlegalized unions" that companionate marriage would eliminate on "the rigidity of the marriage code

promulgated by you and your church." Itching for a fight, he instructed his lecture tour organizers to book

additional stops in Tennessee "where the fundamentalists are stirring up a row against me." Lindsey even

issued an "answer to critics" in early 1927, which he apparently mailed to anyone whose disagreement he

detected from articles he read or letters he received. He announced that he was "bitterly opposed to 'free

love' and so called 'trial marriage'.... I am for monogomy in the love and fidelity of one man for one

10

woman." Lindsey described his opponents as "some of the clergy and others" guilty of "bigotry and

intolerance." He insisted that, contrary to what his detractors claimed, he defended traditional values:

"Thinking people will know I am just as much for the home, for childhood, morality and decency as they

are." Several recipients of the letters protested that, although they disagreed with Lindsey about

companionate marriage, they hardly deserved to be classed as bigots.28

These spats became public relations liabilities for Lindsey. In a letter to Henrietta Lindsey, the judge's 29

wife, one of Lindsey's tour booking agents recommended solo lectures rather than debates, as "so many

people feel that the Judge has run off into a tantrum." Fatigue may have caught up with Lindsey's fury by

the summer of 1927, however, as he accepted the finality of his political losses. Corresponding with his

tour agents, Lindsey complained that "the entire Companionate Marriage subject has been a big loss to me

financially" and doubted that debates with prominent critics would raise his prospects. Indeed, several of

the lectures Lindsey might have relished most, in the Bible belt states of Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi,

and Georgia, had been canceled following protests by local parent-teacher associations and ministers.

Community groups throughout the country blocked Lindsey's appearances in their cities.29

Like Ben B. Lindsey, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, a leader of Reform

11

Judaism (pictured here in 1916), championed the legal availability of

birth control. He regarded companionate marriage, however, as

eugenically reckless. When the two men faced off in a public debate in

January 1928, Wise compared companionate marriage to commercialized

sex. Courtesy Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish

Archives, Stephen S. Wise Picture Collection, PC-4757.

Inconsistencies in Lindsey's argument also left him vulnerable to challenges from theological

30

modernists, many of whom agreed with Lindsey on his major points—the need to legalize birth control and

to liberalize divorce laws. In one of his most famous debates, Lindsey stood opposite Rabbi Stephen S.

Wise (1874–1949) on the stage of Carnegie Hall on January 28, 1928, before a sold-out crowd of thirtythree hundred people. According to the historian Michael A. Meyer, Wise was "one of Reform Judaism's

most aggressive rebels," a social progressive and religious liberal who founded the Free Synagogue in New

York City, the American Jewish Congress (to counter the influence of the patrician-dominated American

Jewish Committee), and a Reform rabbinical seminary in New York. Leading the Jewish charge against

companionate marriage became another cause, and Wise readily accepted Lindsey's challenge to debate. At

the Carnegie Hall debate, Lindsey offered his latest definition: companionate marriage represented, not a

radical revision of marriage, but an acceptance of contemporary practices with the necessary addition of

scientific birth control education.30

Wise objected to companionate marriage on eugenic and moral grounds. Admitting that he agreed with 31

Lindsey's major points, he protested that companionate marriage would lead "not to birth-control but birthsuppression.... Child-bearing would be left to the socially less fit and would be largely avoided by the more

fit." Wise was among what the historian Christine Rosen has described as a group of "modernistic liberal"

clergy of the early twentieth century. Those clergy supported the birth control movement at least in part to

discourage people they considered "unfit" to be parents from procreating. Beyond eugenic concerns, Wise

wondered whether a union that circumvented parenthood could be considered marriage at all: "It may be a

happy and successful mating, it may be better than sex promiscuity, but the essence of marriage, certainly

its crowning glory, is parenthood." Although Wise stopped short of comparing companionate marriage to

prostitution, he likened commitment-free marriage to "a sex-shopping expedition." In the discourse of the

companionate marriage controversy, Wise's objections implied that if companionate marriage came to pass,

it would undermine the sexual ownership implicit in the Judeo-Christian marriage contract. A few months

earlier, Rabbi Louis Newman, who led a Reform congregation in San Francisco, had similarly concluded

that while both he and Lindsey were "modernists" who advocated birth control and were "psychologically

free from the ordinary sex tabus," they differed over whether the "present marriage system" needed to

change or simply to be improved "through education, from within." Wise called on other clergy to help

young moderns learn how to own up to marriage's "responsibilities," rather than to change the social

institution that structured those responsibilities.31

For many laypeople contraception was companionate marriage's principal asset. The public's hunger for 32

information about birth control emerged in numerous letters Lindsey received from individuals desperate to

limit their family size. A woman who lived on the remote Canadian prairie, married fifteen years with four

children, hoped that Lindsey could describe the "harmless" means of birth control to which he alluded in

his Red Book articles, as her doctors refused to tell her about them. She explained that although she and her

husband were "great lovers of babies," they had developed an unsatisfying "system to keep the number

down to normal," a possible allusion to the withdrawal or "rhythm" methods, two of the more common, if

frequently ineffective, means of controlling fertility among people who lacked such mechanical

contraceptives as condoms or diaphragms. Comstock laws sharply curtailed what information could be

published, and many people wrote to Lindsey hoping he could give more detail in a personal letter than he

12

had in his articles. Like the Canadian woman, several other people wrote that they lived in rural areas

where neither doctors nor other authorities disclosed information about sex and where, as one woman

explained, "the only available printed matter seems to be the sensational books advertised in cheap

magazines." One woman from Marietta, Ohio, even challenged Lindsey to amend his opinion on abortion

and to condone it when contraceptives failed. Lindsey felt his deepest professional obligation to these

people. He considered them the victims of benighted Christian virtue.32

Lindsey briefly faded from public view from 1928 until late 1930, due to personal difficulties and a

33

shift in the nation's attention as the economic crisis mounted. Having lost his seat in the Denver court, he

moved to California, was admitted to the California bar, and, by 1934, served on the state's Superior Court.

Like many others, he also followed the allure of Hollywood. Lindsey's cinematic project celebrated his own

ideas: In 1928 he helped produce a film called The Companionate Marriage or (in Great Britain) The Jazz

Bride, a fictional drama loosely based on ideas from his book. Lindsey also continued to lecture throughout

the United States. His public profile rose briefly in 1929 amid news that he had been disbarred in Colorado

for having improperly received legal fees while a sitting judge. Lindsey described the case as yet another

slanderous attack by his adversaries. (He was not readmitted to the Colorado bar until 1935.) To clear his

name—and probably to earn much-needed money—he dictated his memoirs, The Dangerous Life, to the

journalist Rube Borough. Lindsey hoped the book would focus attention on his earlier achievements in the

juvenile court, rather than on his more recent, and less popular, exhortations about sexual morality and

marriage. An invitation to speak before a group of New York Episcopal ministers interrupted work on the

autobiography. Thanks to that lecture, Lindsey and companionate marriage recaptured the national spotlight

one last time in December 1930 in a spectacular, farcical showdown.33

Religion versus Lindsey at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Lindsey made no bones about his impatience with religious leaders who preached chastity and

34

unequivocally condemned divorce. He considered them hypocrites of the worst kind, whose anachronistic

values cultivated the misery they deplored. His accusations came in the midst of deepening gulfs between

theological liberals and newly minted Fundamentalists (an initially pejorative moniker for sympathetic

readers of The Fundamentals, a series of booklets published in 1910–1915 that defended biblical literalism

and rejected modernism). The Scopes "monkey" trial of 1925, in which a Dayton, Tennessee, high school

teacher stood accused of teaching evolution, captured the decade's ambivalence toward religious authority

in public life. In the wake of the trial, religious leaders and laity drew sharp distinctions between modernist

and traditionalist theologies, pitting defenses of historical criticism and relativism against claims of

absolute biblical truth. Conflicts between modernists and traditionalists led to schisms in several

denominations and rancor in others. By casting himself as a crusader against the "superstitions" of faith,

Lindsey seemed to be daring religious conservatives to respond. The Episcopal bishop William Manning

accepted the challenge. In so doing, he gave Lindsey one last public stage, more sensational than all the

others that had preceded it, on which to enact scientific reason's struggle against dogma.34

Manning's views on marriage, sexuality, and religion diverged from Lindsey's, despite some

35

biographical similarities. Like Lindsey, Manning had ascended to the top of his profession but endured the

frustrations of seeing many of his efforts discredited. Standing but five feet four inches tall, "the Little

Man," as both colleagues and detractors called Manning, had become assistant minister of the prestigious

Trinity Church in lower Manhattan at age thirty-six, rector there a few years later, and, by age fifty-five, the

Protestant Episcopal bishop of New York, a position he attained in 1921. He built a reputation for

enhancing the church's physical structure, as he raised funds for the ongoing construction of the

magnificent Cathedral of St. John the Divine in northern Manhattan, and for upholding tradition,

particularly on questions of marriage and divorce. Manning rose to prominence as the social and cultural

influence of the Protestant Episcopal Church was tumbling from its nineteenth-century zenith.

Episcopalians continued to occupy key political posts and were disproportionately represented among

business and professional leaders, but their clergy's influence on questions of politics and morality, like that

13

of other religious leaders, had waned. Protestant denominations' public endorsements of Prohibition,

installed via an increasingly unpopular antialcohol amendment to the Constitution, had further diminished

Protestantism's cultural cachet in the 1920s. A new class of Progressive "experts," steeped in secular social

science, eclipsed religious leaders as authorities in public debates about family life and community values.

Even as the cathedral's towers rose, Manning watched his empire slipping away.35

Manning's orthodoxy placed him at the center of the traditionalist-modernist controversies that were

splitting Protestant denominations. In the early 1920s, as tolerance of divorce and remarriage spread among

Episcopal priests and laity, Manning reiterated his rejection of divorce under any circumstances. In 1926 he

hailed South Carolina, the only state in which all divorce (even for adultery) remained illegal, as an

example of legislative integrity. Manning averred that marital unhappiness might elicit sympathy and

possibly justified separation, but he insisted that sympathy for the unhappily married did not mitigate the

sinfulness of divorce. Ignoring a flood of evidence to the contrary, he argued that stricter divorce laws

could reinforce the leaking sandbags surrounding the sacred citadel of matrimony.36 He viewed

companionate marriage as an attack on his morals and therefore on his God—and, in his role as bishop, on

his vocation.

The decision of the New York Churchmen's Association (NYCA), a group of Episcopalian ministers

over which Manning had no official authority, to invite Lindsey to lecture in late 1930 aggravated

Manning's frustrations with both theological and sexual modernism. Manning disparaged both the

reformers within his denomination and the sexual modernists he believed threatened it from without. A

small number of NYCA members had invited Lindsey to address their December meeting. Manning either

demanded that the NYCA rescind the invitation or, according to his own recollections, called on the

NYCA's leadership to consider the consequences of privileging Ben Lindsey's "immoral" ideas. The group

voted to uphold the invitation, though a few objecting members walked out in protest. Adding insult to

Manning's injury, Rev. Dr. Eliot White, the assistant rector of Grace Episcopal Church and secretary of the

NYCA, announced that he had officiated a few months previously at the companionate marriage of his

twenty-two-year-old daughter and that she had since then adopted, as White euphemistically explained,

"the birth control feature" of the companionate arrangement. However Manning phrased his objections, the

NYCA ignored them, and Lindsey spoke before a capacity crowd at the association's meeting that

December.37

Manning counterattacked, announcing that he would preach a sermon titled "A Message to the Diocese

as to Certain Issues Now Before Us and as to the Meaning of So-Called Companionate Marriage" the

following Sunday. Lindsey retorted that he would be in the audience and that he "might rise up in the midst

of the Bishop's sermon and ask him why he had forbidden his clergy to listen to my address on the same

subject recently." Abandoning the guise of the gentlemanly debater who had faced Rabbi Wise, Lindsey

seemed eager for a bareknuckle brawl. When worshippers arrived at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine on

Sunday morning, December 7, 1930, they encountered uniformed policemen at every entrance and very

likely many curious spectators, as the announcement of Lindsey's challenge had appeared that morning on

the front page of the New York Times. None recognized Lindsey as he entered the church and took a seat in

the front row, even though, a reporter wryly noted, policemen had studied pictures of him the day before.38

From his pulpit that Sunday morning, Manning alternately attacked "a little group of clergymen" who

conspired to undermine his authority and castigated Lindsey for threatening Christian morality and

fellowship. The NYCA's refusal to withdraw its invitation had created a public relations scandal for the

church, Manning warned, and hampered fund raising for the cathedral's construction. The combined threats

from the cabal within the Episcopal Church and Lindsey's "immoral and destructive teachings" threatened

Manning's twin passions: theological tradition and the cathedral intended to honor Christian authority over

a seemingly immoral nation. "The issue of free speech is not involved here," Manning intoned to those who

accused him of stifling the independent NYCA, "but I hold that it was a grave mistake and a shocking

thing, for a gathering of our clergy to give their countenance and endorsement to the former Judge Lindsey

by inviting him in this way." Manning argued that the NYCA's invitation gave the appearance that the

Episcopal Church sanctioned Lindsey's hedonism. As a consequence of that apparent endorsement,

36

37

38

39

14

Manning suggested, Lindsey had recently received an invitation "to present his views to the students at a

well known College for young women." Manning's allusion to this anonymous institution, like the earlier

controversy over the companionate marriage questionnaire at Smith College, seems intended to elicit

racially based fears that companionate marriage would lead young white women away from marriage and

childbearing. Lindsey's ideas, Manning explained, amounted to nothing more than "legalized free love,"

surely something no father would condone for his own daughter.39

At the close of his remarks, Manning called The Companionate Marriage "one of the most filthy,

insidious, and cleverly written pieces of propaganda ever published in behalf of lewdness, promiscuity,

adultery, and unrestrained sexual gratification." Lindsey, who had taken copious notes during Manning's

sermon, set down his pen. His face reddened. Anger threw off his timing, however, for only when Manning

had concluded his sermon, turned toward the altar, and begun, hands lifted, to utter a closing benediction,

did Lindsey respond, jumping from his seat and waving his arms: "I have been misrepresented. If this is a

house of justice I demand five minutes of your time. Bishop Manning, you have lied about me." Though he

later claimed, somewhat disingenuously, that he was "not familiar with Episcopalian ritualism," Lindsey

had interrupted Manning in midblessing. The cathedral erupted into chaos, with cries for Lindsey to be

thrown out. Plainclothes police officers and cathedral ushers grabbed Lindsey and pulled him from the

room. According to accounts, later denied by cathedral officials, one woman yelled out, "You ought to be

lynched," as police hustled Lindsey into a detective's car parked nearby on Amsterdam Avenue and on to

the police station, where he was arrested for disturbing public worship. Lindsey later asserted that he had

been kicked and punched en route from the cathedral to the car.40

As the Bull Mouse rode off in the back of a police car, the Little Man resumed his blessing. His efforts

to rally the congregation initially foundered. Turning to the organist, he called out for "Fight the Good

Fight," a rousing, martial hymn. Dr. Miles Farrow searched his sheet music frantically for the desired score,

as the three thousand people in attendance and an impatient Bishop Manning waited in awkward silence.

Finally, another clergyman located the corresponding number in the Episcopal hymnal, "Hymn 113!" The

music, and Manning's sense of triumph, resumed.41

Press coverage of the cathedral episode portrayed it as a contest between science and religion. Within a

few hours, Lindsey's attorney, Arthur Garfield Hays, intimated to the press that none other than Clarence

Darrow might "take an active interest" in the case, though Darrow silenced those rumors by reiterating his

post-Scopes retirement from the law. Hays himself had a history of defending free speech as an attorney for

the American Civil Liberties Union during the Scopes trial, and several years later he would help represent

the defendants in the Scottsboro case. All charges against Lindsey had been dismissed by mid-December.

Lindsey denounced Manning publicly in lectures, including one at the Shriners' Mecca Temple in midtown

Manhattan before an audience of two thousand people. Deploying scientific analogies, Lindsey explained

that the real debate was over the place of sex within marriage. Bishop Manning and other adherents of

"ancient church doctrine" could fathom only a procreative marital sexuality. Lindsey cleverly identified

such sexuality with a primitive evolutionary stage; he compared the procreative model to behavior "among

domestic animals during mating time for the getting of that species." Sexual moderns, he continued,

recognized a second sexual relationship, the companionate or affectionate expression of marital love.

Castigated from the cathedral pulpit, Lindsey painted himself a twentieth-century Galileo, selflessly

challenging false dogma with the righteous truth of science.42

By contrast, Manning marched in time with the Catholic hierarchy, the only religious group that

condemned Lindsey more fiercely than Manning himself had. Occasionally characterized as a "Catholic"

Episcopalian, Manning invoked Catholic teachings to bolster his defenses of lifelong monogamy and

procreative marriage. Companionate marriage elicited outrage from the highest levels of the Catholic

Church and placed the Catholic hierarchy at the forefront of the twentieth-century defense of procreative,

heterosexual monogamy. In the papal encyclical of 1930, Casti Connubii (Of chaste marriage), Pope Pius

XI directly attacked companionate marriage as a sacrilege. Lindsey, for his part, self-servingly suspected

that his confrontation with Bishop Manning had inspired the pope to write the encyclical. Whatever his

motives, Pope Pius XI objected to companionate marriage chiefly because it led to "frustrating the marriage

40

41

42

43

15

act." Throughout the 1920s, while many other religious organizations in the United States sanctioned

contraception, the Catholic Church combated Margaret Sanger and other birth control advocates. Manning

and the Catholic Church nevertheless fell out of step with the American mainstream—of all religious

persuasions—for whom legal contraception and divorce by mutual agreement would, in time, become

welcome possibilities.43

Religion, Social Science, and "Adjustment"

It is ironic, then, that the companionate marriage controversy ultimately facilitated a productive

44

collaboration between social scientists and some clergy to blame marriage's problems on the individuals

who entered into it, not the institution itself. The sociologist Ernest Groves (1877–1946), a founder of the

marriage education and counseling movements and a devout Christian, influenced how religious and

secular groups approached companionate marriage. He devoted an entire book, The Marriage Crisis

(1928), to refuting The Companionate Marriage. Groves attacked Lindsey for suggesting that the marital

institution required any modifications or adaptations to flourish in the modern world. Marriage did not need

to change, he argued, but poorly adjusted potential marriage partners needed professional assistance to form

successful, monogamous unions. Groves's arguments implicitly denigrated feminism and other attempts to

restructure male-female relationships. Through this reasoning, Groves presented marriage as a normal,

natural, and essentially beneficial arrangement. The eugenicist Paul Popenoe (1888–1979) similarly

rejected companionate marriage in favor of marriage education and counseling. In the late 1920s Popenoe

was in transition from a career as a botanist and an advocate of sterilization of the mentally "unfit" to a

career as a self-styled marriage counselor. Popenoe had first criticized companionate marriage in 1925 in

the Journal of Social Hygiene, where he warned that "companion" marriages provided social sanction for

couples who were "selfish, frivolous, ill-educated, or lacking in normal parental instinct." Higher education

and careers, meanwhile, distracted women from their procreative responsibilities. In 1928, without

mentioning Lindsey by name, Popenoe blasted companionate marriage as evidence of civilization's decline.

What was needed was instruction for parenthood, so that men, and especially women, would grow up to

value childbearing as much as they valued their careers. The first marriage counseling clinics in the United

States, which opened in the early 1930s, accordingly promised to help engaged and married couples adjust

to the demands of marriage.44

Religious organizations across the country began to dedicate resources to studying the marriage crisis, 45

some of them explicitly addressing what they perceived as the deficits of the companionate marriage

model. The Federal Council of Churches of Christ in America (FCC) created a Committee on Marriage and

Home in 1929 to address what it described as a modern calamity. Established in 1908, the FCC provided

Protestants—Episcopalians, Baptists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Methodists, among other

mainline denominations—with an ecumenical vehicle to confront pressing social issues. While those efforts

initially focused on the plight of the workingman, by the late 1920s the liberal-leaning FCC devoted greater

energy to the family. In its first major publication, Ideals of Love and Marriage (1929), the FCC's

Committee on Marriage and Home warned that the companionate ideal overemphasized the contribution of

sexual satisfaction to marital success. The selfish preoccupation with marriage's erotic rewards denigrated

"life-long companionship"—a relationship that led, most importantly, to children. Ruling divorce "a tragic

and humiliating failure," the report traced the roots of that failure to a sexually permissive popular culture,

the availability of contraceptives, and women's emancipation.45

The FCC and other liberal religious organizations faithfully adopted Groves's approach by locating

46

problems outside the institution and within the individuals who neglected traditional marital roles. Like

Groves, writers for the FCC advocated a version of marital cooperation that left traditional gender divisions

unchallenged. The FCC recommended home economics training for women to prevent mismanagement of

household income and a living wage for men so that their wives would not seek employment and leave

their children unattended. Wealthier women needed to return to their mothering duties as well, the report

warned, for "maids and governesses can never wholly take a mother's place, capable as their service may

16

be." The report concluded that churches needed to function as "clinics" that could restore a more

traditionally gendered balance to American families. The capitalist family needed reinforcement, not

reform; men and women must learn how to fulfill their prescribed marital roles as male breadwinners and

female household managers. Other religious bodies, including the Presbyterian General Assembly, the

International Council of Religious Education, and the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), the

professional organization of Reform rabbis, followed the FCC's lead over the next few years and

established committees to promote marriage education and counseling programs. Stephen Wise's Free

Synagogue even opened its own social service center under the direction of Wise's associate rabbi, Sidney

Goldstein, who also headed the CCAR's drive for Jewish premarital counseling.46

Such efforts coincided with broader cultural and political efforts to reinforce masculine family headship 47

during the Great Depression. Hiring policies, public assistance programs, and social commentaries all

highlighted the risks that wage-earning women posed to men's self-image when they challenged men's

status as family breadwinners. Though such policies and programs did not effectively exclude married

women from work force participation, they contributed to a sex segregation within industries and

occupations that consigned women to lower-paid, lower-status jobs. As the historian Anna R. Igra has

noted, women's relationships to men structured their interactions with the emerging welfare state, even as

many women became their families' primary wage earners. Concern with preserving husbands' economic

leadership was also a boon to the birth control movement. Ethnographic studies such as Margaret Jarman

Hagood's Mothers of the South (1939) documented how uncontrolled fertility contributed to unceasing

poverty among white tenant farmers in North Carolina. Scientific contraception could ease burdens on the

welfare state by enabling men to shepherd their families to self-sufficiency. The concern with men's and

women's discrete economic roles within the household did not contradict, but instead encouraged, attempts

by social scientists and clergy to harmonize modern marital relationships.47

Sociologists and practitioners in the new field of "marriage counseling" combined earlier social science 48

descriptions of companionate marriage with new rationales for expert intervention. Evading the phrase

"companionate marriage" and its associations with Lindsey's failed reforms, these sociologists and their

allies instead marked the emergence of a modern ideal of "marital companionship." As Ernest Watson

Burgess, a leading sociologist of the family at the University of Chicago, explained in 1939,

industrialization and urbanization had led to the decline of the patriarchal family and attenuated the

traditional functions of marriage. Marriage had become "more and more a matter of a personal relationship

between husband and wife.... Love and companionship are the personal ties that are replacing the

communal and customary bonds which formerly held husband and wife together." Though marriage had

once provided children's education, health care, and vocational training as well as the setting for food

production and religious observance, its modern form was less capacious. Burgess was a leader in the fields

of family sociology and marriage counseling, and his colleagues adopted his perspective as they offered

guidance to young couples about how to achieve marital companionship. By describing these changes as

sociological epiphenomena, Burgess and others erased agency; marriage had changed, and modern couples

needed help adjusting to it, but active reform was unnecessary and even dangerous. As the foregoing

discussion should make clear, however, democratic marriage did not presuppose gender equality.48

Instead, the language of adjustment in marriage counseling tied the expression of sexual mutuality to

49

the performance of discrete gender roles. Husbands and wives would enjoy sex with one another most fully,

in other words, when they conformed to their masculine and feminine natures. As one marriage counselor

put it in the late 1930s, gender non-compliant people could be "reeducated to the heterosexual point of

view." On one level, heterosexual adjustment involved instructing men and women to be proficient at the

mechanics of sexual intercourse. In shifting their attention to the vicissitudes of heterosexual identity,

however, marriage counselors did not countenance same-sex erotic attraction, its causes, or its implications.

Instead, they believed that psychologically rooted sexual identities would manifest themselves in gendered

behaviors: heterosexual men and women would function as proper husbands and wives. As a result,

counselors might identify homosexual tendencies in clients who neither engaged in nor desired sexual

encounters with individuals of the same sex, but who diverged from gender-based marital ideals.49

17

Amid these efforts to foster marital harmony, clergy and marriage counselors continued to associate

50

Lindsey's brand of companionate marriage with communistic free love—arrangements that allowed "full

marital privileges" but lacked religious or legal sanction. One sociologist defined companionate marriage in

1939 as "not marriage at all but merely premarital intimacy with marriage as a possibility." This negative

definition became grounds for expanding liberal religion's reach into Americans' intimate relationships, a

justification for intervening in couples' relationships to help them make healthy "marital adjustments."

Writing in the mid-1940s, a minister dismissed a bygone era when "there was much talk of trial and

companionate marriage." Thankfully, he continued, that frivolous chatter had turned into more mature

conversations between young people, clergy, and counselors: "Never have young people been so interested