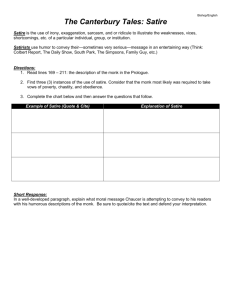

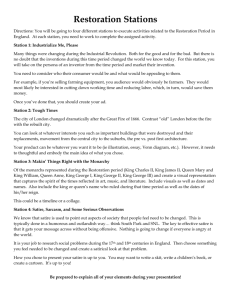

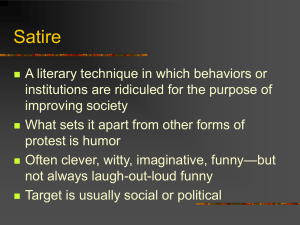

Comedy, Satire and Society

advertisement