Word - 496 KB - Department of the Environment

advertisement

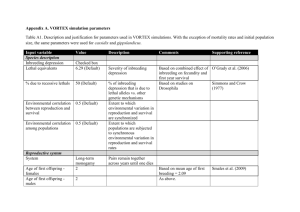

CASE STUDY FROM VICTORIA - EXAMPLE OF TRENDS IN SPECIES AND COMMUNITIES Helmeted honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix Description The helmeted honeyeater is a striking yellow, green and black, medium-sized honeyeater with distinctive yellow crown and ear tufts that contrast boldly with black sides of the head. The upperparts are greenish olive, and underparts yellow to greyish yellow. The forehead carries the distinctive short crest, or helmet, of upstanding yellow feathers which can be pushed forward when the bird is aroused. The helmeted honeyeater is confined to dense riparian forest in the mid-Yarra and Western Port drainages of southern Victoria. All of the current wild population is dependant on remnant patches of Eucalyptus camphora swamp woodland and adjacent Leptospermum lanigerum or Melaleuca squarrosa shrubland. The population of the helmeted honeyeater declined steadily throughout the 1900s until the present recovery effort commenced in 1989. Former colonies at Cockatoo and Upper Beaconsfield died out as recently as 1983 following severe wildfires in February of that year (Menkhorst & Middleton 1991). The last naturally-occurring population comprised 15 breeding pairs and about 50 individuals in late 1989. Through implementation of the first recovery plan, the wild population peaked at about 110 wild individuals, including 27 breeding pairs in March 1996. It has since declined to 12 breeding pairs in the 2007/08 breeding season, confined to a five kilometre length of streamside remnant vegetation along two streams within the Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve (Yellingbo NCR), 50 km east of Melbourne. A second wild population is being established in Bunyip State Park, 70 km east-south-east of Melbourne, through release of captive-bred birds. In January 2008, 34 individuals including nine breeding pairs, had been identified. There are also currently 15 pairs held in captivity at two locations — Healesville Sanctuary, 18 km north of Yellingbo, and Taronga Zoo, Sydney. Significance Using the IUCN categories, the helmeted honeyeater currently rates as critically endangered because: the area of occupancy is less than 10 km2, the population is confined to one locality, and a continuing decline is expected in the area and quality of habitat due to continuing dieback of vegetation at one major colony (IUCN 2001 criterion B2abii,iii,v). The helmeted honeyeater is listed as Threatened in Schedule 2 of Victoria’s Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 and classified as Critically Endangered on the Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria – 2007 (DSE 2007). It is also listed as Endangered under the Commonwealth Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. In 1971 the helmeted honeyeater was chosen as Victoria’s bird emblem. Data and information Close monitoring of population size, dispersion and breeding success is a specialised and labour-intensive task, particularly in the dense swampy habitat of the helmeted honeyeater. The presence of a full-time field ornithologist for much of the recovery effort has led to a precise understanding of population numbers, trend and demographics, information that has been critical to the successes achieved. The helmeted honeyeater has been the subject of a large body of research work, and its life history is particularly well understood. Recent research projects have contributed more detailed knowledge on: nesting behaviour and success (Bartlett 2003; Dare 2003); genetics (Hayes 1999; Mitchell 2001); population ecology (Smales 2004); captive management (Meyer 2005); habitat utilisation (Pearce & Minchin 2001); and the effects of climate on breeding (Chambers et al, 2008). The main gaps in current knowledge concern the broader ecological processes that affect the helmeted honeyeater. In particular, the causes of dieback of stands of eucalypts and melaleucas are poorly understood, with further studies required to unravel the relationships between changed hydrological regimes, nutrient levels, pathogens and insect outbreaks. Little is known about the identity of nest predators, and how to control them to reduce the incidence of nest predation. The reasons for low breeding success amongst captive populations are also poorly understood, with more investigations required to develop strategies to improve breeding success. Management requirements and issues The primary threats to the helmeted honeyeater relate to the small population size and its concentration into a tiny geographic area and isolated linear habitat patches. Wildfire, drought, disease and climate change all have the potential to eliminate the helmeted honeyeater and are forces over which we have little immediate control. Habitat degradation is a serious threat to the helmeted honeyeater. Die-off of stands of eucalypts and melaleucas in parts of Cockatoo Swamp has reduced the area of one important breeding colony by 50 per cent in the last decade. Other threats to habitat are the maturation and lack of regeneration of the Eucalyptus camphora Swamp Woodland, and the spread of tall grass species, including Phragmites australis and the weeds Phalaris arundinacae and Glyceria maxima. Competition for space with colonies of the bell miner Manorina melanophrys has been shown to reduce the breeding success of helmeted honeyeater pairs adjacent to bell miner colonies (Pearce et al. 1995). Although this threat has been eliminated by the removal of selected Bell Miner colonies, the threat of re-invasion by bell miners requires constant monitoring of their occurrence close to helmeted honeyeater colonies. The rate of predation of nest contents reduces population productivity (Franklin & McCarthy 1992), and nest predation may be a significant factor in the decline in Yellingbo 2 ASSESSMENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY 2008 populations. The identity of nest predators has not been established but is likely to include a suite of native mammals, birds and reptiles, as well as the introduced cat, red fox and black rat (Bartlett 2003). Tiger snakes and kookaburras have been photographed removing helmeted honeyeater nestlings at the release area in Bunyip State Park. Nest cameras were used at Yellingbo during the 2008/2009 breeding season to identify nest predators. Management actions and responses The helmeted honeyeater is one of Victoria’s best-known vertebrates, and has been a focus of the wildlife conservation movement in Victoria since the early 1900s. In 1965 the Government of Victoria reserved 170 ha of crown land near Yellingbo containing populations of helmeted honeyeaters spread along three creeks. This reserve was extended to 560 ha in 1975 by joint Victorian and Federal Government land purchases, with a ranger and two support staff appointed. The first national Recovery Plan (Menkhorst & Middleton 1991) focused on population management as well as habitat management, and established the Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Team. A second plan was published in 1999 (Menkhorst, Smales & Quin 1999), with a third plan (Menkhorst, 2007) to be approved in 2008. There is also a Victorian FFG Action Statement (Baker-Gabb 1992) under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988, which is currently being reviewed and updated. Implementation of the recovery plan is the joint responsibility of two Victorian Government agencies – Parks Victoria and the Department of Sustainability and Environment. The Port Phillip and Western Port Catchment Management Authority also has a critical role through the provision of grant money from its Regional Catchment Investment Plan and through implementation of the Regional Catchment Strategy (PPWPCMA 2004). The Shire of Yarra Ranges has a significant role through its powers to limit the destruction of critical habitat on freehold land under the Planning Provisions of the Planning and Environment Act 1987. The Bird Observers Club of Australia has been directly involved in the conservation of the helmeted honeyeater for over 50 years, as has Birds Australia in more recent times. The community group Friends of the Helmeted Honeyeater, established in 1989, has been a major ally to Government agencies involved in the recovery effort, playing an extremely important role in revegetation works, community education and publicity, particularly in the Yellingbo district. These community groups reflect the considerable support for the recovery program within the Victorian community. The Yellingbo NCR lies within the traditional lands of the Wurundjeri-Balluk clan of the Woiwurung language-speaking group of indigenous people, and Bunyip State Park lies within the traditional lands of the Balluk-Willam clan of the Wiowurung. These Indigenous communities have been invited to comment on and be involved in the implementation of the Recovery Plan. ASSESSMENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY 2008 3 Outcomes Although the helmeted honeyeater population is still critically small, it is now bigger than it was before the recovery effort began. The wild populations are now also geographically spread over two locations, which helps increases the overall resilience of the species to the threats of disease, fire, and dieback. Major achievements of the recovery effort since 1991 include: Detailed territory mapping and monitoring of population demographics including the outcomes of all breeding attempts Development of effective techniques for controlling bell miners, to allow expansion of helmeted honeyeater colonies into previously unoccupied habitat. Establishment of new wild populations via release of captive-bred birds, supplementation of wild populations with captive-reared birds (by release of immature birds or by addition of eggs or nestlings to wild nests), and minimisation of the risk of in-breeding via swapping of eggs or nestlings between populations. Exploration of novel decision making tools to assist in the development of management strategies (McCarthy 1995, 1996, McCarthy et al. 1994, 2004, Meyer 2005). Establishment by the Friends of the Helmeted Honeyeater of a vigorous revegetation program on private land surrounding the reserve (Gadsden and Ashby 1995), and at strategic sites within the reserve. Over 300 000 locally indigenous plants have been propagated from seed and planted out (Gadsden 2003). Management plan for Yellingbo NCR published in 2005. Refinement of revegetation techniques and development of priorities for revegetation works within the Yellingbo NCR. Protocol aimed at minimising risks of disease transfer between captive populations produced and implemented. DSE regional fire response plan was updated in 2005 and again in 2007 to further protect the helmeted honeyeater and its habitat within Yellingbo NCR. The success in maintaining existing populations and establishing new ones is primarily due to the efforts of the Recovery Team in protecting existing habitat, monitoring nests for breeding, controlling bell miners, and successfully releasing captive-bred birds into the wild. Captive-bred birds have been released into Yellingbo and have successfully bred, including with wild birds (Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Team data). There have also been encouraging results for the reintroduction of captive populations in the Bunyip State Park. Captive-bred birds were released at two locations, with females dispersing from one site to the other and now known to be breeding. In January 2008, the total population was 27 adults and seven fledglings of the 2007/2008 breeding season; nine breeding pairs had 4 ASSESSMENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY 2008 been identified. This positive result supports the methodology of the current approach to expanding the wild population to more locations. Future scenario The 2008 National Recovery Plan for the Helmeted Honeyeater (Menkhorst, 2007) continues the emphasis of earlier plans on population management, particularly the establishment of new colonies in unoccupied habitat, but also refocusses attention on some difficult habitat rehabilitation problems. The recovery plan has been costed at $2.44 million over five years, and aims to: Increase the number and size of wild populations to attain a wild population of at least 200 mature individuals spread between at least two self-sustaining subpopulations. Maintain and enhance the value of helmeted honeyeater habitat both within its current locale and throughout the former range. Improve the management of stream flows, water quality and riparian environments throughout the Woori Yallock Creek catchment Manage the captive population of helmeted honeyeaters to provide insurance against the demise of the wild population and to meet the needs of the release program Maintain the genetic diversity and evolutionary potential of the helmeted honeyeater Improve public awareness of the helmeted honeyeater recovery program and public support for implementation of this recovery plan The long-term objective of recovery is to achieve a stable population of at least 1000 individuals in at least 10 separate but interconnected colonies dispersed along several creek systems in the mid-Yarra and Western Port catchments, and thus have the taxon removed from Schedule 2 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Conservation of the helmeted honeyeater will necessitate greatly improved catchment management within the former range of the taxon. Attempts to conserve the helmeted honeyeater are already directly responsible for the reservation, intensive management and revegetation of significant remnant vegetation in the Yellingbo region. The primary habitat of the helmeted honeyeater, sedge-rich Eucalyptus camphora Swamp is classified as of National Significance and listed as a threatened community under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988. The helmeted honeyeater recovery plan will closely complement implementation of the Action Statement for this community (Turner 2003). ASSESSMENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY 2008 5 Sedge-rich Eucalyptus camphora Swamp and adjacent vegetation also supports the only remaining lowland population of Leadbeater’s possum, and the swift parrot (both listed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 as endangered). This habitat also supports populations of species of State significance, notably pale swamp everlasting Helichrysum aff. rutidolepis (Lowland Swamps), Lewin’s rail, powerful owl and swamp skink, and regionally significant populations of spotless crake, southern emu-wren, glossy grass skink and showy willow herb. Helmeted honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix. Captive bred at Healesville Sanctuary, released at Yellingbo 2007. Photo: Iain Stych 6 ASSESSMENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY 2008 Helmeted honeyeater habitat, Diamond Ck, Tonimbuk. (Photo: Iain Stych) ASSESSMENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY 2008 7 References Baker-Gabb, D. (1992). Action Statement No. 8. Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix. Department of Conservation and Environment, Melbourne. Baker-Gabb, D. (2002). Major project review of Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix recovery program 1999-2003. Unpublished report to Environment Australia and Department of Sustainability and Environment. Elanus P/L, St Andrews. Barrett, G. Freudenberger, D. and Nicholls, A. O. (2005). A template for threatened species management: learning from the Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix). Unpublished report to Port Phillip and Western Port Catchment management Authority by CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra. Bartlett, L. J. (2003). Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix) nest success: the effect of nest site and the identity of nest predators. BSc Hons thesis, Department of Zoology, The University of Melbourne. Chambers, L. E., Quin, B., Menkhorst, P., Franklin, D. C. and Smales, I. (2008). The effects of climate on breeding in the Helmeted Honeyeater. Emu 108: 15-22. Craige, N. M., Brizga, S. O. and Condina, P. (1998). Assessment of proposed works to ameliorate the effect of hydrological processes on vegetation dieback at Cockatoo Creek Swamp, Yellingbo Reserve. Unpublished Report to parks Victoria by Neil M. Craige Pty Ltd, Croydon. Dare, A. (2003). Contrasting nesting behaviour in captive and wild populations of Helmeted Honeyeaters, Lichenostomus melanops cassidix. BSc Hons thesis, Department of Zoology, La Trobe University, Melbourne. DSE (2007). Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria, 2007. Department of Sustainability and Environment, Melbourne. Franklin, D. & McCarthy, M., (1992). A cost/benefit analysis of protection of Helmeted Honeyeater nests. Unpublished report to the Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Team. Franklin, D., Smales, I., Miller, M. & Menkhorst, P. (1995). Reproductive biology of the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix. Wildlife Research 22: 173-191. Franklin, D., Smales, I., Quin, B. and Menkhorst, P. (1999). Annual cycle of the Helmeted Honeyeater: a sedentary inhabitant of a predictable environment. Ibis. 141: 256-268. Gadsden, G. & Ashby, M. (1995). Revegetation of habitat for the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix, in the Yarra Valley. The Victorian Naturalist 112: 116-121. Gadsden, G. (2003). Nursery News. Friends of the Helmeted Honeyeater Newsletter 15(2): 7-8. 8 ASSESSMENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY 2008 Hayes, V. (1999). Genetic insights into the taxonomy and conservation of the Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix) using microsatellites. BSc (hons) thesis, La Trobe University, Melbourne. Kasel, S. (1999). The decline of Eucalyptus camphora and E. ovata within Yellingbo State nature Reserve, Victoria. PhD thesis, School of Botany, The University of Melbourne. McCarthy, M.A. 1995. Stochastic population models for wildlife management. unpublished PhD thesis, School of Forestry, University of Melbourne. McCarthy, M.A. 1996. Extinction dynamics of the Helmeted Honeyeater: effects of demography, stochastisity, inbreeding and spacial structure. Ecological Modelling 85: 151-163. McCarthy, M.A., Franklin, D.C. & Burgman, M.A. 1994. The importance of demographic uncertainty: an example from the helmeted honeyeater. Biological Conservation 67: 135142. McCarthy, M. A., Menkhorst, P. W., Quin, B. R., Smales, I. J. & Burgman, M. A. (2004). Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix) in southern Australia: Assessing options for establishing a new wild population. In ‘Species Conservation and Management’ ed by Akcakaya, H. R., Burgman, M., Kindvall, O., Wood, C. C., SjogrenGulve, P., Hatfield, J. S. and McCarthy, M. A. Oxford University Press, New York. Menkhorst, P. & Middleton, D. (1991). Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Plan. Department of Conservation and Environment, Victoria. Menkhorst, P., Smales, I. and Quin, B. (1999). Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Plan, 1999-2003. Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Melbourne. Menkhorst, P. (2007). National Recovery Plan for the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix. Department of Sustainability and Environment, Melbourne. Meyer, R. (2005). Determining the optimal captive management of the Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix) using stochastic dynamic programming. MSc thesis, School of Botany, The University of Melbourne. Miller, M. (1995). Husbandry manual for the Yellow-tufted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops. Zoological Parks and Gardens Board, Victoria, Australia. Mitchell, S. (2001). The Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix): Managing the Gene Pool using Microsatellites. BSc Hons. thesis, Department of Genetics, La Trobe University, Melbourne. Mitchell, S. (2006). Woori Yallock Creek Sub-catchment Biodiversity Local Area Plan: Conserving the natural habitat. Department of Sustainability and Environment, Box Hill. Parks Victoria, (1998). Bunyip State Park Management Plan. Parks Victoria, Melbourne. ASSESSMENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY 2008 9 Parks Victoria, (2004). Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve Management Plan. Parks Victoria, Melbourne. Pearce, J. (1997). The delineation and prediction of habitat, with particular reference to the endangered Helmeted Honeyeater. PhD thesis, University of Melbourne. Pearce, J. (2000). Mountain Swamp Gum Eucalyptus camphora at Yellingbo State Nature Reserve: Habitat use by the endangered Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix and implications for management. The Victorian Naturalist 117: 84-92. Pearce, J., Burgman, M.A. & Franklin, D. (1994). Habitat selection by Helmeted Honeyeaters. Wildlife Research 21:53-63. Pearce, J., Menkhorst, P. & Burgman, M.A. (1995). Niche overlap and competition for habitat between the Helmeted Honeyeater and the Bell Miner. Wildlife Research 22: 633646. Pearce, J.L. and Minchin, P.R. (2001). Vegetation of the Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve and its relationship to the distribution of the helmeted honeyeater, bell miner and white-eared honeyeater. Wildlife Research 28(1): 41 – 52. PPWPCMA. (2004). Port Phillip and Western Port Regional Catchment Strategy, 20042009. Port Phillip and Western Port Catchment Management Authority, Frankston. Quin, B. (2003). Out in the Field: Population monitoring report. Friends of the Helmeted Honeyeater Newsletter 15(1): 6. Smales, I. J. (2004). Population ecology of the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix: Long-term investigations of a threatened bird. MSc thesis, School of Botany, The University of Melbourne. Smales, I., Miller, M., Middleton, D. & Franklin, D. (1992). Establishment of a captivebreeding programme for Helmeted Honeyeaters Lichenostomus melanops cassidix. International Zoo Yearbook 31:57-63. Smales, I., Quin, B., Krake, D., Dobrozczyk and Menkhorst, P. (2000). Reintroduction of Helmeted Honeyeaters Lichenostomus melanops cassidix, Australia. Reintroduction News 19:34-36. Species Survival Commission, (2001). IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria, Version 3.1. IUCN – The World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland. Turner, V. (2003). Flora and Fauna Guarantee Action Statement Number 130: Sedge-rich Eucalyptus camphora Swamp. Department of Sustainability and Environment, Melbourne. 10 ASSESSMENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY 2008