doc - GK12 - Arizona State University

advertisement

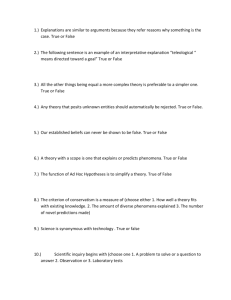

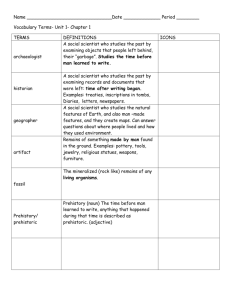

Matter That Matters: Inquiry, Physical Science, and Prehistory Elisabeth V. Culley, M.A. GK-12 Teaching Fellow School of Human Evolution & Social Change Arizona State University . Tempe . AZ elisabeth.culley@asu.edu Lesson Matter That Matters: Inquiry, Physical Science, and Prehistory Driving Question(s) What can matter tell us about prehistory? Target Grade(s) 8th Grade Target Content Standard(s) AZ Science & Technology Strand 1 (Inquiry Process) AZ Science & Technology Strand 5 (Physical Science) Concepts 1-4: Observation, Questions & Hypotheses; Scientific Testing; Analysis and Conclusions; Communication Concepts 1: Properties of Matter and Changes of Properties of Matter Objectives: observe to formulate predictions & hypotheses; design & conduct investigations; record & Interpret data; communicate results Objectives: identify different kinds & states of matter; investigate effects of energy (heat) on matter Summary Matter That Matters was developed as part of the National Science Foundation’s GK-12 Down to Earth Science Program at Arizona State University. As such, the lesson strives to increase science literacy in the 8th grade by using actual research questions to teach age-appropriate concepts and inquiry methods. Matter That Matters recreates an archaeological context in which students design and test hypotheses about ancient stone tools and other technologies. Students apply their pre-existing knowledge about the scientific method and the properties of matter while adopting new analytical procedures. The lesson is a “performance of understanding” for Strands One and Five of the Arizona Science and Technology Standard and underscores the relevance of scholastic content in contemporary scientific research. Matter That Matters also fosters an appreciation of prehistory and the diversity of ancient cultures. Supporting Materials Materials include background information on prehistoric technology and the questions driving the lesson, complete lesson plans, guidance on how to plan for different learning outcomes, and tips on where to locate supplies. The PowerPoint presentation, What Can Matter Tell Us About Prehistory?, provides information on ancient technology for the introductory exercise. The Student Workbook includes worksheets for each learning activity and assessment. Keywords: inquiry, physical science, matter, rocks, minerals, prehistory, archaeology Matter That Matters: Inquiry, Physical Science, and Prehistory Lesson Background & Learning Context We typically think of the physical sciences as a relatively modern endeavor, but people have been observing and manipulating matter for thousands of years. Prehistoric people used to collect rocks and minerals and subject them to extremely high heat. This changed the materials’ physical properties and how they could be used. For example, if noviculite is subjected to extreme temperatures, the molecular bonds are altered so that the rock breaks easily and in a controlled manner. A skilled craftsman can then shape a small piece of stone into a beautiful spear point or awl. If yellow ochre is subjected to high heat, it turns red or brown to form a rich palette of mineral-based pigments. People have been “heat-treating” raw materials to make stone tools, art objects, and other items for well over 15,000 years. Heat-treated artifacts usually indicate a culture had a good understanding of its resources and how to exploit them. However, materials can be heat-treated accidentally when dropped in a smoldering hearth or burned by wildfires. Rocks and minerals that are accidentally heat-treated may or may not be better for making stone tools and other objects. For example, the properties of obsidian will not be altered by heat, while many types of rock and all bone will be damaged. Consequently, when archaeologists discover burned obsidian or bone, they assume the artifact was accidentally heat-treated. Matter That Matters recreates an archaeological research context in which scientists must determine if artifacts were intentionally heat-treated to improve their use-value. The lesson consists of several learning activities, including an introduction to prehistoric technology with hands-on exploration of artifact replicas. Students then apply their knowledge of the scientific method and the properties of matter to determine which materials were heat-treated. More advanced classes should compile and test their results to determine if the materials were intentionally heated for making objects or if they were heated in a wildfire. In requiring students to design and test hypotheses about the properties of matter and how they change, Matter That Matters is a “performance of understanding” for Strands One and Five of the Arizona Science and Technology Standard. In requiring students to use reference samples and compile data, the lesson emphasizes procedures not represented in the Standard, but that are integral to scientific research. Moreover, Matter That Matters underscores the relevance of scholastic content in contemporary scientific endeavors. Time & Materials Matter That Matters requires three class periods to introduce the lesson and to complete both learning activities. The introduction will be most effective if students are able to handle a few artifacts and explore all of the materials that will be used in the learning activities. The activities require three to five different kinds of rocks, minerals, bone, and/or other materials. This lesson plan uses 2-3lbs each of small chert and granite nodules, as well as bone fragments and ground ochre. The materials can be collected locally or ordered on the Internet. Half of each kind of material will need to be heat-treated overnight in an oven or kiln and will constitute the four archaeological samples that the students will be evaluating. Varying the materials that are used and/or which ones are heat-treated will result in different testing outcomes and interpretations of the archaeological record (See Appendix for more information on finding resources, heat-treating materials, and staging different outcomes). From the samples provided, students should conclude that: all of the prehistoric remains have been subjected to high heat; the heating process did not improve the materials for making tools or other items- heat-treating did not increase the number of resources for making objects; therefore, people did not intentionally heat-treat the materials to improve their technology; a wildfire probably heat-treated and changed the properties of the materials. Matter That Matters: Inquiry, Physical Science, and Prehistory Lesson Plan Preparation. Prior to beginning the lesson, half of each kind of material that will be used during the learning activities should be heat-treated, and both the reference samples and archaeological samples, should be labeled by material and sample type. The archaeological samples should be placed at different stations with tools for students to examine each material. Tools should include magnifying glasses, hardness scale, small hammers or mallets, and safety goggles. Stations with ground mineral pigments should also have mortar and pestles and brushes and other supplies for experimental painting. The appropriate naturally-occuring reference sample should be placed at each station for comparisons during Learning Activity One. The Student Workbook includes worksheets for all learning activities and assessments. Introductory Activity: Contextualization & Exploration. The lesson should begin with a brief review of the properties of matter as a means of assessing and correcting pre-existing knowledge and as a means of linking specific content to the learning activities. Students should understand that their knowledge of the properties of matter (****) and how they change will be used to test hypotheses about prehistoric artifacts. Students can learn about prehistoric technology in a variety of ways, and the supplemental materials for Matter That Matters were designed to support a traditional lecture format, demonstrations, and/or hands-on activities. Although it is not necessary for a successful learning experience, teachers are encouraged to contact their local Archaeological Society to have an experienced “knapper”- stone tool maker- demonstrate his or her art. Many students will have visited archaeological sites or found arrowheads, and these experiences can increase the relevance of the lesson. A high level of student interest should be anticipated. Students will need to understand several ideas before exploring the archaeological samples and beginning the learning activities (see the Appendix for further information): 1. People made tools and art objects out of rocks, minerals, bone, and antler 2. Only rocks that fracture concoidally can be used for making stone tools 3. The properties of rocks, minerals, bone, and antler can be changed if subjected to extreme temperatures 4. If some rocks that do not fracture concoidally are heat-treated, their properties will change and they will fracture concoidally; when some rocks are heat-treated they will crumble apart; if some minerals are heat-treated they change colors and increase the number of colors that are available for painting The introductory activity should end with students exploring the archaeological samples and discussing how they would determine if the different materials were heat-treated to improve technology. Students will understand the need to observe the materials’ properties and will likely suggest comparisons with other samples. Teachers will have an opportunity to introduce the use of reference collections and the comparative methods as integral to scientific research. Proper hypothesis formation and testing procedures will need to be scaffolded. Students will be able to make the following statement: “If an archaeological sample has been heat-treated, over half of its properties will be different from the reference sample.” They will also be able to form more specific hypotheses: “If the prehistoric bone has been heat-treated, its color, hardness, and/or style of fracturing will be different from the reference sample.” Students will not recognize that these hypotheses will only test if materials are heat-treated and not if they were heat-treated by people intentionally or wildfire. If students are only to complete Learning Activity One, intentionality does not need to be addressed. If students will complete Learning Activity Two, teachers should explain that the second part of the research question will be answered in the second part of the lesson. Learning Activity 1: Hypothesis Formation & Testing. The first learning activity should begin with a review of the introductory activities and particularly hypothesis formation. Students should work in small groups and choose three of the four archaeological samples to test. Students should record a general hypothesis that can be applied to each of their samples, and they should understand what properties they will examine and how. Each group will investigate their chosen materials, record the appropriate data, and determine which of their archaeological samples was heat-treated. Successful hypothesis formation, testing, and completion of the worksheet constitute assessments for Learning Activity One. Sample Hypothesis: “If samples X, Y, and Z have been heat-treated, over half of their properties will be different from the reference sample.” Follow-up discussions might touch on differences in student conclusions and on using reference collections in science. Learning Activity 2: Collaboration & Inference. Learning Activity Two should begin with a review of the previous activity, including the hypothesis that was tested and why a second hypothesis remains to be tested. Students will need to compile their data and focus on the quality of heat-treated materials to determine if they were altered for tool-making and other purposes or by wildfire. Teacher’s can anticipate that some students will have difficulty using the data they recorded to test the first hypothesis (changed properties/not changed properties) in a different way to test the second hypothesis (improved properties/worse properties). Hypothesis formation and testing should proceed as a group to insure student understanding of why a majority of heat-treated materials that do not improve technology indicate a random process such as wildfire and not intentional human behavior. Class discussions and completion of the worksheet constitute assessments for Learning Activity Two. Sample Hypothesis: “If the archaeological samples were intentionally heat-treated to improve technology, only materials that are improved with heat-treatment will have been treated.” Follow-up discussions might touch on: the need to test two different hypotheses to determine what had happened to the cultural remains; the need to use the conclusions that were drawn in Learning Activity One as the observations for testing the hypothesis in Learning Activity Two; the frustration and importance of learning from unexpected or undesired outcomes. Follow-Up & Final Assessment. Matter That Matter introduces new research domains (archaeology) and analytical procedures (reference samples, data compilation, collaboration) to 8th grade inquiry. Depending on time limitations and students’ experience, teachers may want to conduct a follow-up assessment several days after the lesson has been completed. Concepts and questions from class discussions and student worksheets can be revisited. Suggestions have been included in the Student Workbook. Appendix On Prehistoric Technology On Heat-Treating Rocks and Other Materials Staging Different Outcomes Meeting Different Learning Objectives Finding Resources