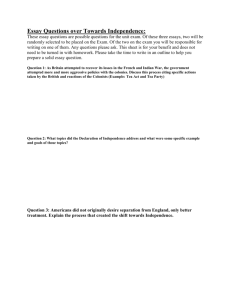

History Essay Handbook

advertisement