Richard III & Looking for Richard: Comparative Study

advertisement

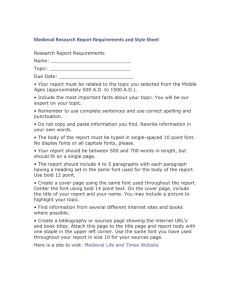

Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Module A: Comparative Study of Texts & Contexts Elective 1: Exploring Connections Richard III & Looking for Richard Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Concept: Contextualisation and Connections - Exploring Connections through Texts and Contexts Key Question: How does the exploration of the nature of connections of two texts and their contexts connected by the enigmatic Richard III enable you to have greater understanding of both texts? Key Learning Ideas: 1. Context: How and why does Richard III and Looking for Richard reflect their social, cultural and historical context? The effects of social, cultural and historical context and questions of value on aspects of texts How changes in context lead to changed values being reflected in texts 2. Connections: What do we learn about Richard III and Looking for Richard by exploring the connections between them? How meanings of a pair of texts can be shaped and reshaped by considering the nature of the connections between them Connections through direct or indirect references, contexts, values, ideas, and the use of language forms and features 3. Perspectives: How can we account for the continuing resonance of Shakespeare’s Richard III? The language of texts, the purposes and audiences, and the content, values and attitudes conveyed through a range of readings 4. Responding: How do you respond to the exploration of these two texts and their contexts and what meanings have you gleaned from the study of the connections? How to compose a range of imaginative, interpretive and analytical compositions that relate to the comparative study of texts and context Outcomes: Assessment Task: 1, 2, 2A, 10, 12A Texts & Resources: Outcome 1. A student explains and ‘Pacino states in Looking for Richard Looking for Richard & Richard III evaluates the effects of different contexts ‘What's this thing that gets between us Kott, J. (1974). Shakespeare Our Contemporary. New York: Norton Books of responders and composers on texts. and Shakespeare?’ How and why Richard III, does Pacino attempt to connect a http://www.shakespearetheatre.org/_pdf/first_folio/folio_richardIII_about.pdf Outcome 2. A student explains relationships among texts. modern audience with King Richard Richard III Society, (Lesson plans and notes), Outcome 2A. A student recognises III?’ http://www.r3.org/pacino/lesson3.html different ways in which particular texts American Richard III Society, (Annotations with historical and contextual are valued. explanations and notes), http://www.r3.org/bookcase/shaksper/index.html Your task is to present your Outcome 10. A student analyses and Richard III, The making of a Legend, (Historical notes on Richard) Oh, Tey synthesises information and ideas into perspective of Pacino’s question and sustained and logical argument for a Can You See, (War of the Roses – a brief overview), the task question through a range of purposes, audiences and http://www.r3.org/bookcase/murph1.htmlRichard III, A Study in conversation between Shakespeare contexts. Historiographical Controversy, (History of Richard), and Pacino. This conversation can be Outcome 12A. A student explains and http://www.r3.org/bookcase/shaksper/kosir.html Van Elk, M. (2007). recorded as a podcast or a written evaluates different ways of responding to "Determined to prove a villain": criticism, pedagogy, and Richard III.’ transcript. You can include one or and composing text. more speakers who are from the texts or are commenting on the texts. Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Rationale ‘Shakespeare is like the world, or life itself. Every historical period finds in him what it is looking for and what it wants to see’ (Kott, J. Shakespeare Our Contemporary, 1974, p.5). You will find the comparative study of King Richard III and Looking for Richard engaging and stimulating. The representation of the much maligned Richard by Shakespeare and Pacino is contentious and the artistry of both texts is evident. Module A is a comparative study of two texts through an exploration of their different contexts and values. You are expected to investigate and consider the effects of social, historical and cultural context and questions of value. Remember, that the rubric provides the framework for the HSC examination so you need to understand the key concepts of this module and the elective. The concepts are: Contextualisation In Module A you are directed to explore the effects of social, historical and cultural context. Thus, you are considering the society and its culture and values at the time the text was composed, and the historical events that influenced the text. Once you have ascertained the context of the two texts you need to examine the ways in which changes in context lead to changed values being reflected in texts. Values are the beliefs and attitudes of the composer and may shift to reflect those of the society at the time. They are conveyed directly and indirectly through the world of the text and the characters’ words and actions. Another aspect of this module that you must consider is a range of readings. An effective and meaningful way to do this is to examine how context shapes the different ways that Pacino, others and you have responded to the play and the different readings by Shakespeare, Pacino, others and you of Richard III. Connections This is the main focus of the module and Elective 1 that is entitled pointedly ‘Exploring Connections’. From the beginning of your study of the texts you must be examining the relationship between the texts in terms of context, and how the meanings of a pair of texts can be shaped and reshaped by considering the nature of the connections between them. The comparison could be the similarities and/or differences. You will make these implicit and/or explicit connections initially through your thesis and then through the contexts, values, ideas and the language features. Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director SYLLABUS CONTENT TEACHING AND LEARNING STRATEGIES AND ACTIVITIES QUALITY TEACHING Week 1 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 2.2 2.3 2A.1 2A.2 Introduction to Module A, the key concepts and ideas and the texts Module A is a comparative study of two texts through an exploration of their different contexts and values. You are expected to investigate and consider the effects of social, historical and cultural context and questions of value. Remember, that the rubric provides the framework for the HSC examination so you need to understand the key concepts and key ideas of this module and the elective. The two main concepts are: Contextualisation The effects of social, historical and cultural context. Thus, you are considering the society and its culture and values at the time the text was composed, and the historical events that influenced the text. You need to examine the ways in which changes in context lead to changed values being reflected in texts. Values are the beliefs and attitudes of the composer and may shift to reflect those of the society at the time. They are conveyed directly and indirectly through the world of the text and the characters’ words and actions. Connections The relationship between the texts in terms of context, and how the meanings of a pair of texts can be shaped and reshaped by considering the nature of the connections between them. The comparison could be the similarities and/or differences. You will make these implicit and/or explicit connections initially through your thesis and then through the contexts, values, ideas, the language features and characterisation. Key Ideas Prior knowledge: Revisit background knowledge of context and values Deep knowledge: Focus on the key concepts and key learning ideas of Module A Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director The key ideas and the overarching question you will need to be able to respond to by the end of your exploration of the module and the two texts are: Context How and why does Richard III and Looking for Richard reflect their social, cultural and historical context? The effects of social, cultural and historical context and questions of value on aspects of texts How changes in context lead to changed values being reflected in texts Connections What do we learn about Richard III and Looking for Richard by exploring the connections between them? How meanings of a pair of texts can be shaped and reshaped by considering the nature of the connections between them Connections through direct or indirect references, contexts, values, ideas, and the use of language forms and features Perspectives How can we account for the continuing resonance of Shakespeare’s Richard III? The language of texts, the purposes and audiences, and the content, values and attitudes conveyed through a range of readings. How context shapes the different ways that Pacino, others and you have responded to the play and the different readings by Shakespeare, Pacino, others and you of Richard. Responding How do you respond to the exploration of these two texts and their contexts and what meanings have you gleaned from the study of the connections? Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director How to compose a range of imaginative, interpretive and analytical compositions that relate to the comparative study of texts and context Activities 1. View the trailer (DVD or YouTube) of Looking for Richard and discuss your response to Pacino’s mission and what is conveyed about Shakespeare and the character of Richard. 2. Discuss as a class what context and values mean. Individually reflect on how your context and experiences have shaped your values and attitudes. 3. You must have a sound understanding of the context of the play and the documentary. Use the internet to research the texts and record relevant information in the table that you will generate for Activity 1 - See Activity Sheet 1. The American Richard III Society’s site http://www.r3.org/bookcase/shaksper/index.html has excellent information on both texts and links to other good sites. 4. Begin reading Shakespeare’s play Richard III and keep a reflective record of your response to the ideas in the play, its values and the character of Richard. Use extracts from a range of films such as McKellan’s version and Looking for Richard (the scenes where the actors are performing) to arrive at a clear understanding of the characters and ideas rather than read around the class. 5. As the relationship between the texts is the major focus for Module A, create a comparison table that you add to as you learn more about the texts and their contexts. Ensure that you include relevant and precise key quotes. See Activity Sheet 1. Week 2 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 2.1 2.2 2.3 Contextualisation This week we continue our exploration of the contexts of the texts and its influence on meaning. As you read about the social, historical and cultural contexts of the composers, consider how your own context is impacting on the way you are responding to the two texts and how the examination of the connections between the texts may be altering your response. Shakespeare’s context and values Knowledge integration: Links to History Substantive communication: Analysis and discussion of key Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director 2A.1 2A.2 6.1 10.1 12A.1 12A.2 King Richard III performed around 1591 explores the consequences of the individual’s relentless pursuit of power reflecting the central focus of most of Shakespeare’s tragedies and history plays, and as art imitates life it is the continuing story of humanity’s history. As Jan Kott observes in Shakespeare Our Contemporary: ‘history is like a great staircase on which there treads a constant procession of kings...every step upwards is marked by murder, perfidy and treachery...every step brings the throne nearer...another step and the Crown must fall...from the highest step...there is only a leap into the abyss...’ In the 21st century the pursuit of power is still evident; thus, providing one explanation for the continuing resonance of King Richard III. Shakespeare’s main source for King Richard III was Holinshed’s The Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland published in 1587. Holinshed based much of his information on Polydore Vergil’s history of the English monarchy commissioned by King Henry VII in 1485. Sir Thomas More’s The History of King Richard III published in 1543 that demonised Richard became the major source for Shakespeare’s representation of Richard as a villain. More grew up in the household of the Bishop of Ely, John Morton, who had been imprisoned by Richard III: Richard, the third son, of whom we now entreat, was … little of stature, ill-featured of limbs, crook-backed, his left shoulder much higher than his right, hard-favoured of visage … He was malicious, wrathful, envious and from afore his birth ever forward. By casting Richard as a villain Shakespeare is affirming to his Elizabethan audience of the emergent middle class and the nobility the Tudor’s legitimate right to the throne. Richmond who defeats Richard at the Battle of Bosworth and becomes king of a united England was Henry Tudor, the greatgrandfather of Elizabeth 1, the ruling monarch when this play was performed. However, no Shakespearian play is so simple. The play reflects the tension between providentalism and the growing secular interest in free will. The triumph of Richmond at the end of the play and his accession to the throne of England when considered in the light of the tetralogy of the history plays that reflect the cycle of the struggle to acquire power, the succession to the throne and then the defeat of the king, does not signify a triumph for providentialism. Richmond ironically gets away with seizing the crown rather than going through the more legitimate channels: aspects and concepts of the two texts and the elective and a class debate on the key issues Narrative: Engaging with the story of Richard and his times Higher-order thinking: Analysis of key concepts of context and representation Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director While on the face of it, Richmond seems to fulfill God's plan with a heroic masculinity to match, combining contradictory Christian and warrior mentalities, few critics are now content to read him as a positive replacement for Richard (Van Elk, M. ‘Determined to prove a villain’: criticism, pedagogy, and Richard III’, 2007, p.4). Aspects Political unrest and the persecution of Catholics: These are very cruel, turbulent and tense times when those in power were aware of their vulnerability. Thus, anyone who threatened their power was imprisoned, banished or beheaded. King Richard III was written during the Elizabethan period when Elizabeth 1 had survived numerous threats to her reign. As well as being politically correct in its support of the reigning Tudors, the play would have captured the imagination of an audience aware of the ongoing political intrigue and power struggle. The role of the theatre: In 1558 Queen Elizabeth issued a decree controlling the performance of plays; all scripts were subject to censorship. Sir Francis Walsingham, the Queen’s spymaster, founded The Queen’s Men in 1583 as a political mouthpiece. Their role was to spread Protestantism and royalist propaganda through a divided realm. Shakespeare was a young actor in company. The cultural and political role of theatre in this period further reflects the intent of King Richard III that advocates the political rights of the Tudors and maligns Richard III and the House of York. Machiavellian politics: Niccolo Machiavelli who lived in Italy from 1469 to 1527 asserted in his work The Prince (1513) that an effective ruler should abandon the traditional notions of virtue and morality and maximise power to ensure his own survival at any cost. ‘Politics have no relation to morals.’ According to Machiavelli who was writing to secure the favour of the ruling Medici family, a charismatic leader with strong skills, intuition and an eloquent command of language could easily have absolute power. ‘A wise ruler ought never to keep faith when by doing so it would be against his interests.’ Machiavelli’s view of politics and power represents a humanist move towards a new, secular notion of leadership. Richard III is partially a Machiavel who seemingly rejects traditional Christian virtues and morality to pursue at any cost personal power and who uses language as a persuasive and seductive weapon. Shakespeare does not deplore the Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Machiavel rather he explores the personal and social costs of the pursuit of individual power. Morality plays and the Vice: The earlier Christian Morality plays served to illustrate the central moral struggle of the Christian soul to remain true to the teachings of the Church. One of the most popular and influential figures in these plays was the Vice (the devil) whose role was to tempt Everyman to succumb to temptations. The Vice established a close rapport with the audience through jokes, tricks and asides representing the seductive power of the devil. Although the character of Richard III has its origins in the Vice as he reminds the audience – ‘Thus like the formal Vice, Iniquity, / I moralise two meanings in one word’ - he is more subtle and human. His actions rather than his nature are evil. An academic in Looking for Richard states ‘Already in this play he is thinking about human beings as actors and about the stage.’ Secularism and free will (Humanity having control over destiny)vs. providentialism (God’s will and what is ordained to happen in life): Shakespeare’s times reflect a shift from humanity’s unquestioned relationship with God to a more secular exploration and fascination of what it is to be an individual with free will. As Hamlet wisely observes ‘What piece of work is a man?’ The play conveys clearly this tension as the character of Richard is a blend of the secular Machiavel and the providential Vice character. Values Richard III The representation of Richard by Shakespeare as an unscrupulous, ruthless villain who pursues power relentlessly and only momentarily regrets his actions reinforces core values that have been evident in Shakespeare’s other plays: Integrity Honesty Loyalty Moderation Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Activities 1. Discuss what is significant about Shakespeare’s context in terms of his representation of Richard and his values. 2. Discuss whether the values that are evident in this play are still important to a modern audience and to young people. 3. Discuss the significance of the emergence of free will and an interest in humanism as opposed to providentialism during Shakespeare’s time, and what the reality is today and why. 4. Continue your reading of the play and making notes in your comparison table. Pacino’s connection to Richard III and the context ‘How do communicate to an American audience?’ From the opening of the documentary the audience is aware of Pacino’s intent: ‘It has always been a dream of mine to communicate how I feel about Shakespeare to others.’ Pacino’s purpose and quest is to connect Shakespeare’s universal themes and his powerful language with the everyday public; thus, his journey is to discover how people regard Shakespeare and why an enigmatic character like Richard III could still be appealing and relevant to a modern audience. ‘We're peddling him on the streets.’ Pacino encounters people who find Shakespeare ‘boring’ and ‘no kind of connection is made. His claim is that Shakespeare the writer and actor should be enjoyed by all, ‘Our main goal with this project is to reach an audience that would not normally participate in this kind of language and world.’ The contextual focus of the documentary is essentially social and cultural with Pacino exploring why and how a modern audience could and should connect with Shakespeare. Looking for Richard released originally in 1996 was produced for an American audience that had experienced Shakespeare on stage and the screen but who according to Pacino and his actors, and reinforced by the impromptu interviews on the streets, were sceptical about the relevance of his plays and resistant to the complexity of the language. Kevin Kline in the documentary states: An English teacher brought us to a local production of ‘King Lear’ and after ten minutes of Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director people doing "Shakespearean acting"; I tuned out and started making out with my girlfriend in the back row. We left at intermission. Everyday people on the street criticise Shakespeare’s plays or plead ignorance and disinterest. But an African American on the street whose responses are used strategically throughout the documentary counters the negative responses celebrating the artistry of Shakespeare’s language and the significant moral values in his plays that he believes have been lost in our modern world: When we speak without feeling, we get nothing from our society. We should speak like Shakespeare. We should introduce Shakespeare into our academics. You know why? 'Cause then the kids would have feelings. We have no feelings. That's why it's easy for us to get a gun and shoot each other. We don't feel for each other. If we were taught to feel, we wouldn't be so violent. Values Pacino’s purpose is to bring Shakespeare to the American public so that it is not confined to academics and dry texts. Kimball, his assistant states ‘Actors truly are the possessors, the proud inheritors of the understanding of Shakespeare!’ Pacino pursued this project for four years. He was determined to achieve his goal of producing a documentary that would make Shakespeare accessible to everyone. The African American interviewed on the street apart from praising the artistry of Shakespeare’s language speaks of the value of teaching Shakespeare to young people so that they learn about the significance of empathy and feeling for others, ‘We have no feelings.’ As Pacino’s reading of the play reinforces the dominant reading the same core values are conveyed. However, there are the added values of: Empathy Egalitarianism Perseverance Activities Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director 1. Polarised class debate: ‘Why study a dead person! Shakespeare is no longer relevant to modern audiences!’ 2. What are your core values? Discuss whether Pacino’s values have relevance to young people. 3. Discuss what is significant about Pacino’s context that would influence him to repeat Shakespeare’s representation of Richard as a villain. 4. Class discussion on how the contextual information provided shaped your understanding of the play and the documentary. Week 3 1.1 1.5 2.1 2.2 2.3 2A.1 2A.2 6.1 12A.1 12A.2 Textual Form and Structure To explore the connections between the texts you need to consider the textual forms and structures. Richard III The play classified in the First Folio as a historical tragedy continued the story of the power struggle in England from Henry VI Part III and concluded the historical tetralogy that began with King Richard II. Each of the history plays dealt with the struggle for the English crown detailing the long and bloody civil wars of the fifteenth century. Shakespeare adopts a providential view of history as an organising framework and draws on the Vice character of the Christian Morality play (a medieval allegory that represents the transition from traditional miracle plays to renaissance drama) to create a play that is beginning to reflect the modern fascination with the central character. However, Richard moves beyond the Vice figure and a Machiavel (see notes earlier on Machiavelli) as he is very human and even heroic in places. The play’s rising action builds to the moment when Richard is crowned king and then rapidly falls with Richard descending into darker deeds and others deserting him until the final battle scene where he is killed and Richmond triumphs. As Pacino observes wisely ‘As soon as he gets what he wants…the emptiness.’ Activities Prior knowledge: revisiting dramatic structure of a play Deep understanding: Creation of a comparative table based on analysis and exploration of the two texts Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director 1. To broaden your understanding of the Christian morality play and the Vice figure, and Machiavellian politics search the internet such as Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morality_play - and the New World Encyclopedia http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Morality_play - for relevant information. You do not need to have a deep understanding of both but it will at least provide a framework for Richard III. 2. Plot visually the movement of the play – visit http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dramatic_structure for a clear explanation of dramatic structure: exposition – background information and setting for Richard rising action – conflict building with Richard pursuing his goal of power climax or turning point – Richard achieves his purpose and then the events turn suddenly (occurs very early in the play) falling action – Richard’s plans unravel denouement or catastrophe – Richard is defeated Looking for Richard The documentary is a stream-of-consciousness drama documentary that took four years to make. The use of the hand-held camera and the random interviews on the street reinforce Pacino’s purpose to bring Shakespeare to the general public. The importance of the reaction of the person on the street is represented in the beginning of the documentary by the close ups and tilted up camera angles on their faces as they respond to Pacino’s questions. The documentary’s structure sequentially follows the narrative of King Richard III so that the viewer is reminded of the importance of the play and the continued fascination with the character of Richard III, and guided through the plot. The documentary opens and ends with Prospero’s famous lines from The Tempest reminding the viewer that the play and the documentary are merely constructs and that ‘we are such stuff that dreams are made on, / And our little life is rounded with a sleep’. The documentary is a deliberate pastiche of cuts from interviews with actors and scholars juxtaposed with impromptu vox pops with people on the streets of New York City to demonstrate the wide appeal Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director of Shakespeare. This is exemplified in the opening scenes that begin with Penelope Allen performing Elizabeth’s lines. Then there is a jump cut to the actors discussing their interpretation of the play’s characters layered with the non-diegetic voiceover of Redgrave pondering the complexity of Shakespeare’s words. This is followed by an interview with an African American who passionately remonstrates that as Shakespeare’s plays are about morality and convey significant values everyone should have to study them. Critics have accused Pacino of making a documentary that is more about Pacino than looking for Richard. James Bowman of The American Spectator states: It is a film based on the by-now old-fashioned notion that Shakespeare can be made "relevant" to the happening youth of the nineties…But I doubt the efficacy of slicing and dicing Shakespeare and serving him up in quick cuts to pander to a bunch of no-mind slackers. Activities 1. Continue reading the play and making notes in the Activity 1 comparison table. Note how Looking for Richard follows the narrative structure of the play so as you read and discuss the play in class view the relevant sections of the documentary. Week 4 1.1 1.3 1.4 1.5 2.1 2.2 2.3 2A.1 2A.2 6.1 10.1 Textual features and details You are asked to make connections between the texts through textual features and details such as the ideas and the language features. This week we will be exploring the main ideas in Richard III and how Looking for Richard reflects those ideas. As you record notes on the ideas in your Activity 1 comparative column ensure that you are considering and recording the language features and the characters’ actions and relationships that convey these ideas. Substantive communication: Class debates and discussions exploring the key ideas of the texts; composing a transcript that explores significant aspects of the texts and the elective Ideas The consequences of the pursuit of power Higher-order Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director 10.2 12A.1 12A.2 The pursuit of power is paramount in King Richard III. Richard is not the only character who betrays, manipulates, kills and lies his way to obtain power and control. The actors in Looking for Richard are fascinated by the battle for power and the hatred that is palpable, ‘They are clawing at each other for the throne!’ They compare the play to the film The Godfather – ‘The gathering of the Dons in this room.’ Thus, Looking for Richard makes the connection between Elizabethan times and modern times stressing that there will always be individuals who will betray others for power. As Redgrave states in the film, The truth is that those in power have total contempt for everything they promise, everything they pledge, and this is really what Shakespeare’s great play is really about. thinking: Synthesising what has been learnt about the texts and the elective in a transcript Deep understanding: Evidence of understanding of the Shakespeare illustrates the terrible consequences of suppressing your humanity for power. His villains texts in an extended die alone without respect or love. Pacino observes that Richard ‘has no friends’ and the academic states response that Richard ‘knows that he does not even have his own humanity. He has lost it!’ Richard himself concludes honestly, ‘There is no creature loves me, / And if I die no soul shall pity me.’ (Av, siii) Activity 1. Match the key quotes from the play and the documentary that refer to the pursuit of power and analyse what is being said and how it is said. 2. Discuss whether the pursuit of power and its consequences is still relevant. Explore why and how? Conscience - How far are we prepared to go? Even at the end when Richard has been confronted by the ghosts of those he killed and betrayed he exclaims, ‘O coward conscience, how dost thou afflict me?’ (Av, siii) not seek salvation. The play is an exploration of how individuals can ignore their conscience and commit evil such as the murderers of Clarence who hesitate only for a moment before taking his life or Buckingham who supports Richard until he makes the mistake of having to consider whether he supports the murder of the two young princes, ‘He did all the dirty work and propped up the king.’ Like Pacino, we are fascinated by the compelling, unscrupulous Richard III who seduces us through his soliloquies and asides to be coconspirators, and shocks us with his lack of conscience: Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director This guy Richard...make up your mind...what is he? First you say he’s a kind of devil, then you say he’s a kind of mad court jester. Then, he’s a dead ringer for a kind of medieval Vice. Whatever that is? And then he’s described as some sort of scourge of god or Machiavelli, and somehow at the end we’re meant to feel some pity for him...weird? Activity 1. Class debate: ‘The end justifies the means.’ Two speakers for and against and the class divided in half supporting the two opposing teams. Free will vs. providentialism Richard III is determined as are many of Shakespeare’s villains to orchestrate his own destiny. Richard states that he is ‘determined to prove a villain’; however, this is a pun referring to the conflict between his free will and his destiny to be a villain. Queen Margaret continually reminds him of God’s will and providence. Although the defeat of Richard supports providentialism, Shakespeare’s representation of Richard as a seductive and charming villain provokes thought about the tension between free will and determinism, and represents the renaissance struggle between secularism and providentialism. As Looking for Richard reflects a secular world there is minimal reference to providentialism, but the documentary does dwell on Richard’s determination to construct his own destiny. Pacino considers through Richard what it is to be human: our motives, needs, ambitions and flaws: Let’s get this right, this guy Gloucester, has killed Anne’s husband and father-in-law and the father-in-law’s body starts to bleed when he comes by and he still manages to win the girl? And then he says he doesn’t even want her. Come on... Human frailty and mortality ‘What, do you tremble? Are you all afraid? /Alas, I blame you not, for you are mortal…’ (A1, s.ii) Richard’s acquisition of power cannot be attributed solely to his manipulative skills; the moral weakness of the other characters facilitates his success. As Machiavelli states in The Prince ‘It is Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director double pleasure to deceive the deceiver.’ Lady Anne is fully aware of what Richard has done yet she is seduced by his flattery and agrees to marry him. Richard judges her weakness accurately. Clarence fears death because he has killed others to increase his power ‘I have done those things, /That now give evidence against my soul…’ (A1, siv). When the murderers come to kill him, Brackenbury’s inaction is attributed to the desire to protect his reputation, ‘I will not reason what is meant hereby, / Because I will be guiltless of the meaning’ (A1, siv). Even the anonymous murderers argue about morality before killing Clarence. The Archbishop is persuaded by Richard to hand the young princes over to him removing the protection of the church. Even Richard is vulnerable. He is represented physically and psychologically as an outsider rendering him very human. He explains from the opening of the play that he is deformed, crippled and incapable of love: Cheated of feature by dissembling nature, Deformed, unfinish’d, sent before my time Into this breathing world, scarce half made up, And that so lamely and unfashionable That dogs bark at me as I halt by them’ (AI, si). Duplicity Richard III is never what he seems. He is only honest with the audience informing them of his plans and celebrating his success. He uses irony skillfully to hide his ruthlessness and lack of conscience. Even after all of the bloody deeds he is able to convince the people, albeit for a brief time, to support him. As Pacino sings gleefully ‘He’s got the whole world in his hands!’ Activity 1. To build on your understanding of the importance of making connections through the texts compose a 750-word transcript of a meeting between Shakespeare, Pacino, Richard III and coproducer of Looking for Richard Michael Hadge who are discussing the ideas and values of the play, the representation of Richard and their different contexts. This activity could be made Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director richer and more enjoyable by involving the whole class and getting them to represent other characters from the play and actors and/or academics and people on the street. Instead of composing a transcript record the discussion and keep it as a podcast that can be used for future revision. Week 5 1.1 1.4 1.5 2.1 2.2 2.3 2A.1 2A.2 6.1 10.2 12A.1 12A.2 Textual features and details Language The power of Shakespeare’s language: the nuances, lyricism, the delicious irony and dramatic techniques have ensured that his plays have been canonized. In Looking for Richard, when the actors discuss the ambiguity and complexity of the lines in the play and how they should interpret these lines they convey to the viewer the duality of both the magnetism and refutation of Shakespeare’s artistry. When the actors present with passion their lines or the key lines of the play are repeated in the documentary, the artistry of Shakespeare’s language is evident. The language in King Richard III is rich and colourful, and used effectively by Richard to manipulate others and cement his power. Richard frequently employs irony, powerful rhetoric and clever word play to seduce others and the audience. He moves beyond the formal structure of traditional rhetoric to the compelling use of imagery. Imagery and striking metaphors flourish in King Richard III and are used to symbolically represent Richard’s villainy: The wretched, bloody, and usurping boar, That spoiled your summer fields and fruitful vines, Swills your warm blood like wash, and makes his trough In your embowelled bosoms… (Richmond, AV, scii) The use of antithesis throughout the play forcefully expresses the tension and conflict in the play, and even our own ambivalent attitude towards Richard. Vanessa Redgrave speaks lyrically in Looking for Richard of the power and emotion of Shakespeare’s use of language - ‘the beauty, depth, passion, music of his words.’ The African American who is Deep understanding: Focus on key aspect of language of the texts Deep knowledge: Creation of a comparative table and activities that require demonstration of an appreciation and comparison of the texts Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director interviewed on the street speaks eloquently about how words today have lost their meaning and emotions, ‘If we felt what we said, and say less we’d mean more.’ Despite the gravity of the play, Shakespeare cleverly reflects the bitter sweetness and irony of life through humour. The humour in King Richard III predominately comes from the character of Richard and his wicked use of irony and puns. An academic in Looking for Richard refers to the power of irony in the play defining it as ‘Irony is really only hypocrisy with style.’ He uses humour to seduce the audience and lighten the seriousness of his crimes. Whereas the humour in King Richard III is sardonic the humour in Looking for Richard is light-hearted, satirical and almost Monty Pythonish! The documentary ends with childish humour whereas in the play Richard loses his humour. Activities 1. Redgrave refers to the artistry of Shakespeare’s language. Form a team of two or more and find an extract in the play that your team believes is the most effective. Perform the extract and then explain why this extract was selected. Refer to the use of language and the meaning that is conveyed. 2. In Looking for Richard the key scenes of the play are presented. One of these key scenes is the wooing of Ann. Firstly analyse the language of the scene in the play Richard III where Richard woos Anne and the meaning that is conveyed about the characters and the key ideas. Secondly, discuss why Pacino chose to feature this scene and analyse how Wynona Ryder and Pacino deliver (voice, gesture, body language and movements) these lines in the documentary. 3. If you were the director of Looking for Richard what is one scene that you would have featured? Justify your choice. 4. Continue to add to the Activity 1 comparative column. Week 6 1.1 2.2 2.3 2A.1 2A.2 A range of readings – The Representation of Richard ‘And every tale condemns me for a villain. There is no creature loves me; Problematic knowledge: Consideration of a range of readings of the play and Richard Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director 6.1 6.4 10.1 10.2 10.3 12A.1 12A.2 12A.3 And if I die, no soul shall pity me…’ (AV, sciii). All productions of King Richard III from the British productions featuring Garrick, Kean or Olivier to the modern productions casting Richard as a fascist such as those featuring Sher or McKellen, unquestionably accept Shakespeare’s representation of Richard as a villain. Jan Kott whose reading of Richard III has influenced many modern productions such as Hall’s 1963 production where Richard’s soldiers resembled Nazis wearing jackboots reaffirms Shakespeare’s representation asserting that ‘We must find in it the night of Nazi occupation, concentration camps, mass murders’ (1974, Shakespeare our Contemporary). Pacino has continued this reading of Richard’s character in Looking for Richard. The representation by Shakespeare of Richard as a manipulative villain has provoked a range of extreme readings and given birth to international Richard III Societies that fight to clear his name. During Shakespeare’s time Sir Thomas Moore’s accounts of Richard had gained hold of the public’s imagination – ‘Friend and foe were indifferent; where his advantage grew, he spared no man’s death whose life stood in his purpose…’; ‘He was malicious, wrathful, envious…’ His suspected execution of the young princes cemented his place in history as a villain. Shakespeare’s misrepresentation perpetuated this perception. Richard is accused by Shakespeare of: Being deformed and ugly: In the Elizabethan period an imperfection such as a hunchback was indicative of a defect of the soul. Richard’s deformity would have been seen as retribution for the wrongs of his ancestors and motivation for Richard’s pursuit of evil. Wooing Anne Neville alongside the corpse of her father-in-law Henry VI – murdered by Richard in the Tower of London. Murdering Prince Edward – aged 17 - son of Henry VI at the Battle of Tewksbury (1471) and Anne’s husband. Ordering the death of his brother Clarence. Ordering the murder of the young princes Edward and Richard in the Tower. Poisoning his wife Anne Neville in 1485 so he could marry his niece Elizabeth of York and sister of the two princes. The real Richard Plantagenet was born into a violent age. To put Richard into context of his own violent age is not to make him morally a better man, but at least it makes him more understandable. In the climate of high politics of his own day, his mistakes may then be seen as errors of judgment rather Deep understanding: Demonstration of appreciation of others’ perspectives in representation and performance Substantive communication: Discussing and writing at length on a key consideration of the elective Higher-order thinking: Consideration of a range of readings and own reading of Richard Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director than moral failures (http://www.r3.org/bookcase/shaksper/rossnote.html#5). At the age of eight, he was to learn that his father, Duke Richard of York, had been killed in battle, and that his elder brother, Edmund of Rutland, then aged seventeen, had been brutally murdered afterwards. Twice he suffered exile as a consequence of the civil war. Most of the men he had known in youth were either killed in battle or judicially murdered for their alleged treason, among them his mentor, Richard Neville, earl of Warwick, himself no mean practitioner in the arts of political ruthlessness, and another brother, George duke of Clarence, killed in the Tower in 1478. Warwick taught Richard lessons in the killing without trial of his political opponents, especially in his illegal dispatch of William Herbert, earl of Pembroke, in 1469. Both the executions of Rivers, Grey and Vaughan at Pontefract without trial in 1483 and Richard's various illegal actions in regard to property committed both during the Protectorate and after the failure of the 1483 rebellion, are a direct legacy of this instruction. Historical records inform us that Richard III was a deeply religious man who provided for: The First legal aid system and bail for offenders Reform of oppressive land tenure laws. Francis Bacon referred to him as ‘a good lawmaker who legislated for the ease and solace of the common people.’ His support of the common people led to opposition by the nobility. Archibold Whitelaw, Scottish envoy, September 1484 states ‘There is the excellent and outstanding humanity of your innate benevolence, your clemency, your liberality, your good faith, your supreme justice, and your incredible greatness of heart.’ Croyland reported on hearing of Richard’s death at the Battle of Bosworth, ‘King Richard was pierced with many mortal wounds and fell in the field like a brave and most valiant prince.’ The productions, including Looking for Richard, have firmly focused on the universality of the themes and ideas of King Richard III and explored the actions and motives of Richard reflecting a liberal humanist reading. Pacino represents Richard as deformed with a hump, a deformed arm and a limp and he dwells on his thirst for power and the bloody deeds. Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Activities 1. There have been a range of readings of Looking for Richard. Find two conflicting reviews on the internet and record the positive and negative opinions. Compare them with your own response to the documentary. Share your perspective with another student. 2. Discuss what is significant about Shakespeare and Pacino’s context in terms of their representation of Richard as a villain. 3. How do you read Richard? Imagine that you have been asked to direct a modern version of the play. How would you represent Richard? Consider his appearance, dress, movements, the delivery of his lines and his relationship with others. 4. Analyse the soliloquy where Richard reflects on his deeds and how others view him. At the end of this soliloquy he ceases the castigation and resolves to face what will come. As a class discuss how this soliloquy could be read and performed. The class is to experiment with a range of ways to deliver the lines. 5. Create a visual representation of Richard using ICT that features quotes from the play and Looking for Richard as well as images from a range of productions and films. Weeks 7 - 8 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 2.1 2.2 2.3 2A.1 2A.2 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 10.1 10.2 Preparing for the HSC and the Assessment Task Ensure that you read over the syllabus and prescriptions rubrics and go to the Board of Studies site to read the Notes from the Marking Centre. These notes provide excellent feedback on the features of better scripts. E.g. Candidates who clearly understood the purpose of their texts were able to demonstrate conceptual understanding and respond personally. High-range responses used key terms particular to their focus area to create their own thesis, and displayed an ability to evaluate and analyse. Better responses developed a thesis which demonstrated a strong conceptual understanding of the module and the elective. Note that you are expected to have a deep conceptual understanding of the nature of a comparative study and the texts you are exploring in this elective. Substantive communication: Responding at length to the texts through the framework of the elective Deep understanding: Demonstrating through extended responses insight into the texts through a comparison Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director 10.3 12A.1 12A.2 12A.3 12A.4 Activities Successive feedback from the HSC marking centres has stressed the importance of developing a thesis that demonstrates a strong conceptual understanding of the module and the elective. Thus, you are expected to be able to present a clear thesis that is judiciously supported by strong textual analysis connected through context. To prepare you for this challenging task complete the following activities: 1. Develop a series of mind maps connecting King Richard III and Looking for Richard through some of the aspects covered in this chapter such as the ideas, language and a range of readings. Some possible theses are: - ‘Looking for Richard connects the audience to Shakespeare through the exploration of the enigmatic Richard III.’ - ‘While the context, language and form have changed, Shakespeare and Pacino are fascinated by Richard and represent him as a villain.’ - ‘Both King Richard III and Looking for Richard are products of different times yet they are connected through their exploration of what it is to be human.’ - ‘Looking for Richard reconnects us with Shakespeare's characters and themes reminding us that they are timeless. We can look for Richard, and find him, in the world around us.’ 2. Using the extract below as a starting point, analyse the ways in which a comparative study of The Tragedy of Richard III and Looking for Richard invites reflection on what motivates and shapes our actions in life. ‘And every tale condemns me for a villain. There is no creature loves me; And if I die, no soul shall pity me…’ The Tragedy of Richard III Compose an extended response to this question. Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Module A: Comparative Study of Texts & Contexts Elective 1: Exploring Connections Outcomes to be assessed: Outcome 1. A student explains and evaluates the effects of different contexts of responders and composers on texts. Outcome 2. A student explains relationships among texts. Outcome 2A. A student recognises different ways in which particular texts are valued. Outcome 10. A student analyses and synthesises information and ideas into sustained and logical argument for a range of purposes, audiences and contexts. Outcome 12A. A student explains and evaluates different ways of responding to and composing text. Language modes to be assessed: Reading and writing Key learning ideas: - Context: The effects of social, cultural and historical context and questions of value on aspects of texts How changes in context lead to changed values being reflected in texts Connections: How meanings of a pair of texts can be shaped and reshaped by considering the nature of the connections between them Connections through direct or indirect references, contexts, values, ideas, and the use of language forms and features Perspectives: The language of texts, the purposes and audiences, and the content, values and attitudes conveyed through a range of readings Responding: How to compose a range of imaginative, interpretive and analytical compositions that relate to the comparative study of texts and context Nature of task: ‘Pacino states in Looking for Richard ‘What's this thing that gets between us and Shakespeare?’ How and why does Pacino attempt to connect a modern audience with King Richard III?’ Your task is to present your perspective of Pacino’s question and the task question through a conversation between Shakespeare and Pacino. This conversation can be recorded as a podcast, a blog, a wiki or a written transcript. You must include at least one other speaker from the texts or who are commenting on the texts. The conversation should be approximately 1000 words. You Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director are not marked on your ICT skills but whether the way you use language is appropriate for your audience, purpose and form. The conversation must focus on: The composers’ intended meaning conveyed in the texts. How the social, cultural and historical context and questions of value have shaped the texts and their meaning. Different ways that the composers and others have responded to and composed texts such as the interpretation and representation of Richard III or the interpretation of Shakespeare’s play. The connections between the texts such as the continued fascination with Richard III and the universality of the ideas in Shakespeare’s play. Remember that the quality of your response will be enhanced by an overarching thesis or line of argument such as: ‘Looking for Richard reconnects us with Shakespeare's Richard III reminding us that his ideas, craft and his enigmatic Richard are timeless. We can look for Richard, and find him in the world around us.’ You will be assessed on how well you: Demonstrate understanding of how values and context shape meaning Explains and evaluates different ways of responding to and composing texts Evaluate the relationships between texts and contexts using detailed and relevant textual references Compose a conversation using language appropriate to audience, purpose and form Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director MODULE C: Elective 1: MARKING GUIDELINES Criteria Marks Demonstrates an insightful understanding of how values and context shape meaning Evaluates skilfully the relationships between texts and contexts using detailed textual references Explains and evaluates insightfully different ways of responding to and composing texts Composes a skilful conversation using language appropriate to audience, purpose and form Demonstrates a thoughtful understanding of how values and context shape meaning Evaluates effectively the relationships between texts and contexts using relevant textual references Explains and evaluates thoughtfully different ways of responding to and composing texts Composes an effective conversation using language appropriate to audience, purpose and form Demonstrates a sound understanding of how values and context shape meaning Evaluates soundly the relationships between texts and contexts using some relevant textual references Explains with some evaluation different ways of responding to and composing texts Composes a sound conversation using language appropriate to audience, purpose and form Demonstrates a limited understanding of how values and context shape meaning Makes connections between texts and contexts with limited textual references Describes in a limited way different ways of responding to and composing texts Composes a limited conversation using some aspects of language appropriate to audience, purpose and form Attempts to show an understanding of how values and context shape meaning Elementary reference to different ways of responding to and composing texts Attempts to make connections between texts and contexts with elementary or no textual references Attempt to composes a conversation A 13 - 15 B 10 - 12 C 7-9 D 4-6 E 0-3 Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Activity Sheet 1 Comparison Table King Richard Connections III Context: social, historical and cultural Audience and purpose Key Quotes & Meaning through analysis of language features & Form Looking for Richard Key Quotes Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Values and attitudes A range of readings of the play and the character of Richard Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Form Content Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Ideas Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Language features Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Date Event and Play Reference October 2, 1452 Richard born at Fotheringhay (7th son; 4th to survive) 1456 Anne Neville born 1459 Duke of York in exile in Ireland November 1459 Duke of York's estates are confiscated June 1460 Edward of March invades from Calais July 10, 1460 Edward captures Henry VI at Northampton September 1460 Duke of York returns to Wales, claims the throne and is named Henry VI's heir December 30, 1460 Queen Margaret's Lancastrian army defeats the Yorkists at the battle of Wakefield. Duke of York and Earl of Rutland killed. February 2-3, 1461 Edward of March defeats the Lancastrian army at the battle of Mortimer's Cross February 17, 1461 Queen Margaret's Lancastrian army defeats Warwick at second battle of St. Albans Spring 1461 Duchess Cecily of York sends George and Richard to the Duke of Burgundy for safety March 4, 1461 Edward of March declared King Edward IV March 29, 1461 Edward IV defeats the Lancastrians at the battle of Towton June 1461 George and Richard return from Calais June 26, 1461 George and Richard made Knights of the Bath June 28, 1461 Edward IV crowned (at 18 years old) November 1, 1461 Richard made Duke of Gloucester Late 1461 Richard enters household of the Earl of Warwick at Middleham Castle August 12, 1462 Richard granted lands and titles (but little income or power) October 2, 1462 Richard appointed Admiral of England, Ireland & Aquitane (another empty title) Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director May 1464 Edward IV marries Elizabeth Woodville May 1465 Elizabeth Woodville crowned Queen Late 1465 to late 1468 or early 1469 Richard placed in the custody of the Earl of Warwick 1466 Princess Elizabeth born 1468 Richard's sister Margaret marries the Duke of Burgundy June 18, 1469 Edward IV learns of Warwick and Clarence's rebellion July 4, 1469 Clarence marries Isobel Neville July 26, 1469 Edward IV loses to rebels at battle of Edgecote. King emprisoned at Warwick and Middleham Castles September 10, 1469 Edward IV free in York October 1469 Edward IV and Richard are back in London October 17, 1469 Richard created Constable of England November 7, 1469 Richard replaces Lord Hastings as Chief Justice of North Wales February 7, 1470 Richard replaces Warwick as Chief Steward and Chamberlain of South Wales February 1470 Warwick and Clarence rebel again March 1470 Clarence is promised Warwick's lands March 12, 1470 Edward IV disperses rebels at 'Lose-Cote' Field May 1470 Warwick and Clarence flee to France July 25, 1470 Anne Neville betrothed to Edward of Lancaster as part of deal between Warwick and Queen Margaret August 26, 1470 Richard leaves Wales and becomes Warden of the West Marches toward Scotland September 1470 Warwick's army sails for England October 2, 1470 Edward IV and Richard flee for Low Countries Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director November 2, 1470 Edward, Prince of Wales born March 11, 1471 Edward IV and Richard return to England April 14, 1471 Edward IV defeats Warwick (and kills him) at the battle of Barnet May 4, 1471 Edward IV defeats Queen Margaret and the remaining Lancastrians at the battle of Tewkesbury. Richard leads the vanguard. Prince Edward of Lancaster is killed and Queen Margaret is taken prisoner. May 18, 1471 Richard named Great Chamberlain and Constable & Admiral of England (and other titles and grants) May 21, 1471 Edward IV returns to London & Henry VI dies. (Act I, sc. 1) May 20, 1472 Clarence given Richard's title of Great Chamberlain February 17, 1472 Anne Neville and Richard agree to marry. Richard begins battle with Clarence over Anne's share of Warwick's lands (Act I, sc. 2) March 25, 1472 Clarence created Earl of Warwick and Salisbury Easter 1472 Anne Neville and Richard marry November 1473 Edward IV takes back the land he granted to Clarence May 1474 Warwick's lands split between Anne and her older sister Isobel disinheriting their mother. 1475 Richard accompanies Edward IV on invasion of France 1478 Clarence accused of treason by act of parliament (Act I, sc. 3) February 15, 1478 Richard's son created Earl of Salisbury (one of Clarence's titles) February 18, 1478 Clarence executed in the Tower Act I, sc. 4 February 21, 1478 Richard regains title of Great Chamberlain and Clarence's share of Warwick lands (Act II, sc. 1) 1481-1483 Scottish Wars 1482 Queen Margaret dies in France April 9, 1483 Edward IV dies (at 40 years old) (Act II, sc. 2-3) April 14, 1483 News of Edward's death reaches the Prince of Wales at Ludlow Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director April 17-20, 1483 Funeral rites for Edward IV April 20, 1483 Richard travelling slowly towards Northampton April 24, 1483 Prince leaves Ludlow for London April 27, 1483 Council (excluding Richard & Buckingham) decides coronation date of May 4 and other administrative matters April 29, 1483 Prince seized from Earl Rivers at Stony Stratford by Richard &Buckingham April 30, 1483 News of seizure of Prince and arrest of Rivers reaches London (Act II, sc. 4) May 4, 1483 Prince arrives in London with Richard and Buckingham and 500 men (Act III, sc. 1) May 10, 1483 Council meets and sets new coronation date of June 24th (later changed again to June 22nd). Richard named as Protector and other changes in great offices made. Buckingham receives spectacular list of new powers/titles/lands. June 9, 1483 Negotiations with Queen Elizabeth to leave sanctuary break down June 10-11, 1483 Richard sends letters to the north asking for aid against the Queen and the Woodvilles June 13, 1483 Lord Hastings arrested and executed. Lord Stanley arrested. (Act III, sc. 2 & 4) June 16, 1483 Cardinal of Canterbury sent to sanctuary to persuade the Queen to release the Duke of York. June 17, 1483 The Duke of York is released into Richard's custody. Preparations for coronation stopped. Parliament scheduled for June 25 cancelled. (Act III, sc. 1) June 20, 1483 Prince and Duke of York's attendants withdrawn (approx). Clarence's son brought to London and placed in the custody of his aunt, Anne Duchess of Gloucester June 22, 1483 Richard claims the throne through Ralph Shaw's sermon at St. Paul's Cross June 24-25, 1483 Buckingham advances Richard's claim in a speech at the Guildhall and to an assembly of lords and gentry. The assembly draws up a bill petitioning Richard to take the throne. (Act III, sc. 5) June 25, 1483 Rivers, Grey, Vaughan and Haute beheaded at Pontefract (Act III, sc. 3) Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director June 26, 1483 Buckingham, the assembly, the mayor and aldermen of London presented the petition to Richard at Baynard's Castle. Richard agrees and assumed the throne. Coronation date fixed for July 6 (Act III, sc. 6-7) July 6, 1483 Richard III crowned (Act IV, sc. 1) Summer 1483 Edward V and Duke of York probably killed July 13, 1483 Richard III promises Earldom of Hereford to Buckingham (Buckingham is richest landowner in England) (Act IV, sc. 2) July 21 to September, 1483 Richard III makes first "progress" September 8, 1483 Richard III and Anne's son invested at Prince of Wales October 11, 1483 Duke of Norfolk responds to Buckingham's rebellion with orders to muster troops October 12, 1483 Richard III aware of Buckingham's rebellion. He is surprised and shocked. (Act IV, sc. 3-5) October 15, 1483 Unusually severe storm floods rivers and cuts off Buckingham; also scatters Henry Tudor's fleet November 2, 1483 Buckingham, betrayed by a servant, is executed (Act V, sc. 1) November 8, 1483 Richard III at Exeter, Henry Tudor and rebels flee to France November 25, 1483 Richard III back in London December 25, 1483 Henry Tudor pledges to marry Elizabeth of York if he gains the throne, rebels give homage. January 1484 Rebels attainted for treason, their offices filled by northerners, as were following openings January 23, 1484 Richard III holds his only parliament; Richard III's bastard daughter Katherine married to William Herbert, earl of Huntingdon March 1, 1484 Dowager Queen Elizabeth and her daughters leave sanctuary early April 1484 Richard III and Anne's son, Edward Prince of Wales, dies May 1, 1484 Richard III issues general order of array against possible invasion Karen Yager Northern Sydney Region Professional Learning & Leadership Coordinator & ETA Director Summer 1484 War with Scotland continued September 1484 Three year truce with Scotland signed; Henry Tudor leaves Brittany for France November 1484 France grants Henry Tudor funds for an army December 3, 1484 Henry Tudor and the rebels denounced in a general proclamation December 8, 1484 Richard III again issues general order of array against possible invasion early 1485 Queen Anne falls ill January 1485 Richard III issues warrant to knights, esquires, etc. in Chester to obey Lords Stanley, Strange and Sir William Stanley March 11, 1485 Richard III's bastard son John appointed captain of Calais March 16, 1485 Queen Anne dies and Richard declares to the Council that he does not intend to marry Princess Elizabeth June 22, 1485 Richard III issues next set of commissions of array June 23, 1485 Henry Tudor and allies are proclaimed to be "murderers, adulterers and extortioners" July 31 - August 1, 1485 Henry Tudor sails from Harfleur August 7, 1485 Henry Tudor lands at Mill Bay August 9, 1485 Henry Tudor lands at Milford Haven. Richard III at Nottingham August 11, 1485 Richard learns of Henry's landing and sends out letters demanding instant support from supporters August 14, 1485 Duke of Norfolk receives Richard's summons at Framlingham Castle in Suffolk August 15, 1485 Henry Tudor at Shrewsbury (News reaches York) August 21, 1485 Henry Tudor at Atherstone in Warwickshire August 22, 1485 Henry Tudor defeats Richard III at Bosworth and is proclaimed King Henry VII (Act V, sc. 2-5)