The Richard III Diet: Wild Birds, Frequent Feasts and - School-One

The Richard III Diet: Wild Birds,

Frequent Feasts and Plenty of Wine

By WILLIAM GRIMES AUGUST 18, 2014 4:56 PMAugust 18, 2014 The New York Times

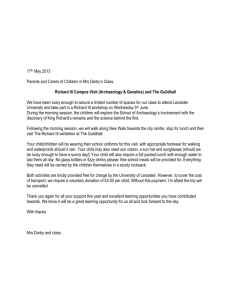

A stained glass window depicting Richard III with his wife and son at the visitor's center on the site where his remains were discovered, in Leicester, England.

Credit Leon Neal/Agence France-

Presse — Getty Images

It is good to be king, even if only for two years. British researchers analyzing the bones of

Richard III have found that Shakespeare’s most nefarious royal lived high on the hog after taking the throne, at age 30, in 1483. Even by the lofty standards of the nobility, he dined sumptuously and drank lavishly, judging by chemical traces left in his skeleton and examined, using multi-isotope techniques, by scientists at the British Geological Survey and the University of Leicester . Their findings were posted online by the Journal of Archaeological Science .

The researchers studied parts of two teeth, a femur and a rib to develop a picture of Richard’s life from childhood to his untimely death in 1485 on Bosworth Field . By analyzing oxygen and strontium isotope data, they were able to draw conclusions about his geographical locations and his diet. For instance, they found evidence to support historical accounts that Richard moved at age 7 or 8 from Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire to Ludlow Castle in Shropshire.

Photo

A replica of Richard III's skeleton on display.

Credit Leon Neal/Agence France-Presse — Getty

Images

After wresting the crown from the House of Lancaster and placing it upon his own head, Richard proceeded to enjoy the fruits — or rather the meats — of victory. The historical record shows that his coronation banquet included such luxury items as cygnet, crane, heron and egret, and it seems that he was able to keep the party going, since his remains suggest an increased consumption of freshwater fish and wild fowl, available only to the wealthy. Nor did he stint on wine, judging by the chemical record, which suggests a significant uptick in consumption. All in all, life was good.

“We know he was banqueting a lot more; there was a lot of wine indicated at those banquets; and tying all that together with the bone chemistry, it looks like this feasting had quite an impact on his body in the last few years of his life,” Angela L. Lamb, a scientist at the Isotope

Geosciences Laboratory of the British Geological Survey and a member of the research team, told the BBC . “Richard’s diet when he was king was far richer than that of other equivalent high-status individuals in the late medieval period.”