Jaudice - TMA Department Sites

MINISTRY OF HEALTH OFTHE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN

CENTER OF DEVELOPMENT OF MEDICAL EDUCATION

TASHKENT MEDICAL ACADEMY

Department of infectious and pediatric infectious diseases

Subject: Infectious diseases

THEME:

EARLY AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

JAUNDICE SYNDROME

Educational-

methodical guideline

for teachers and students of Treatment Faculty

TASHKENT

MINISTRY OF HEALTH OFTHE REPUBLIC OF UZBEKISTAN

CENTER OF DEVELOPMENT OF MEDICAL EDUCATION

TASHKENT MEDICAL ACADEMY

"A F F I R M E D"

Pro-rector of educational work

Professor Teshaev O.R.

__________________________

«____»____________2012

Department of infectious and pediatric infectious diseases

Subject: Infectious diseases

THEME:

EARLY AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

JAUNDICE SYNDROME

Educational-

methodical guideline

for teachers and students of Treatment Faculty

"

A F F I R M E D"

at a DNC meeting of Therapeutic Faculty

Protocol № ___from_________2012

Chairman of DNC

, Professor

Karimov M.Sh.___________

TASHKENT

2

SUBJECT: EARLY AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

JAUNDICE SYNDROME

1. Place of the lessons, equipping

- The auditorium; ;

- Separation of viral hepatitis;

- Box Office;

- Outpatient department;

- Diagnostic department;

- The emergency room;

- Laboratories (clinical, biochemical, bacteriological, immunological);

- TCO: Case patients with HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, HEV, slaydoskop; TV-video, teaching, supervising the program, methods of work scenarios in small groups, case studies.

2. The duration of the study subjects

Number of hours - 18

3. The purpose of classes

- To develop skills in an integrated approach to clinical diagnosis of infectious diseases with the jaundice syndrome, management of laboratory studies in primary care to teach rational therapy in the home, personal preventive health examinations and rehabilitation of convalescents viral hepatitis;

- to familiarize students with the basic clinical and laboratory syndrome of jaundice;

- when parsing the topics at the bedside of an individual patient, in laboratories and in the classroom, to bring interest to the profession, to stimulate the process of self-education, and develop a sense of responsibility and compassion to the sick;

- as an example, parsed thematic issues to develop scientific thinking, to stimulate creative approach to solving non-standard clinical tasks and the ability to make independent decisions. To develop logical thinking and ability to express their thoughts on professional language.

Objectives

The student should know:

- The differential diagnosis of the syndrome of jaundice in viral hepatitis and other common infectious diseases;

- The differential diagnosis of the syndrome of jaundice in viral hepatitis and jaundice of noninfectious origin;

- Early rational laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases with the jaundice syndrome;

- Preparation of a diagnostic algorithm for finding the presence of jaundice in a patient;

- The principles of the treatment and rehabilitation of patients with viral hepatitis;

- Specific and nonspecific methods of prevention.

The student should be able to:

- To conduct a professional history and examination of the patient;

- Establish a preliminary diagnosis on the basis of early and differential diagnosis;

- Appoint a targeted survey;

- Interpret data from laboratory and instrumental methods of examination;

- Own clinical decision-making logic (to form a definitive diagnosis, to assess the severity of the patient's condition and prognosis);

3

- To diagnose the state of emergency and to provide first medical aid in the pre-hospital;

- Decide whether to send the patient for a consultation or hospitalization and the corresponding stationary;

- To rehabilitate convalescence of viral hepatitis.

As a result of training the student should learn practical skills:

Skills 1st order

- Examination of the patient;

- To take blood for serology;

- To define the bile pigments in the urine;

- To take blood for biochemical research;

Skills of 2nd order

- Interpretation of laboratory data;

- Provide the necessary assistance to the pre-hospital;

- To provide emergency assistance in PEI;

- To hold the primary control measures in the outbreak of viral hepatitis.

4. Motivation

Rising incidence of viral hepatitis in the past decade, increasing numbers of patients with chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis of the liver, as well as the presence of the syndrome of jaundice in a number of infectious and noninfectious diseases determine the need for physician ownership of

GPs supporting clinical and laboratory symptoms of infectious diseases associated with jaundice.

5. Interdisciplinary communication

Teaching this topic is based on the knowledge bases of students of biochemistry metabolism, microbiology, immunology, pathological anatomy, pathological physiology, physiology of the biliary tract. The data and knowledge found in the studies will be used during the passage of medicine, surgery, obstetrics, gynecology, hematology and other clinical disciplines.

6. The content of training

6.1. The theoretical part

Jaundice (also known as icterus; attributive adjective: icteric) is a yellowish pigmentation of the skin, the conjunctival membranes over the sclerae (whites of the eyes), and other mucous membranes caused by hyperbilirubinemia (increased levels of bilirubin in the blood). This hyperbilirubinemia subsequently causes increased levels of bilirubin in the extracellular fluid.

Concentration of bilirubin in blood plasma does not normally exceed 1 mg/dL (>17µmol/L). A concentration higher than 1.8 mg/dL (>30µmol/L) leads to jaundice. The term jaundice comes from the French word jaune, meaning yellow.

Jaundice is often seen in liver disease such as hepatitis or liver cancer. It may also indicate obstruction of the biliary tract, for example by gallstones or pancreatic cancer, or less commonly be congenital in origin.

Yellow discoloration of the skin, especially on the palms and the soles, but not of the sclera and mucous membranes (i.e. oral cavity) is due to carotenemia - a harmless condition important to differentiate from jaundice.

The conjunctiva of the eye are one of the first tissues to change color as bilirubin levels rise in jaundice. This is sometimes referred to as scleral icterus. However, the sclera themselves are not

"icteric" (stained with bile pigment) but rather the conjunctival membranes that overlie them.

The yellowing of the "white of the eye" is thus more properly termed conjunctival icterus. The term "icterus" itself is sometimes incorrectly used to refer to jaundice that is noted in the sclera

4

of the eyes, however its more common and more correct meaning is entirely synonymous with jaundice.

When a pathological process interferes with the normal functioning of the metabolism and excretion of bilirubin just described, jaundice may be the result. Jaundice is classified into three categories, depending on which part of the physiological mechanism the pathology affects. The three categories are:

Pre-hepatic/ hemolytic

Hepatic/ hepatocellular

Post-Hepatic/ cholestatic

Pre-hepatic

Pre-hepatic jaundice is caused by anything which causes an increased rate of hemolysis

(breakdown of red blood cells). In tropical countries, malaria can cause jaundice in this manner.

Certain genetic diseases, such as sickle cell anemia, spherocytosis, thalassemia and glucose 6phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency can lead to increased red cell lysis and therefore hemolytic jaundice. Commonly, diseases of the kidney, such as hemolytic uremic syndrome, can also lead to coloration. Defects in bilirubin metabolism also present as jaundice, as in Gilbert's syndrome

(a genetic disorder of bilirubin metabolism which can result in mild jaundice, which is found in about 5% of the population) and Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

In jaundice secondary to hemolysis, the increased production of bilirubin, leads to the increased production of urine-urobilinogen. Bilirubin is not usually found in the urine because unconjugated bilirubin is not water-soluble, so, the combination of increased urine-urobilinogen with no bilirubin (since, unconjugated) in urine is suggestive of hemolytic jaundice.

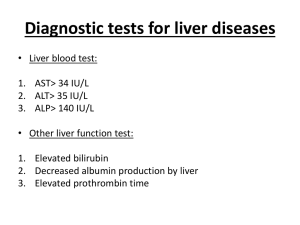

Laboratory findings include:

Urine: no bilirubin present, urobilinogen > 2 units (i.e., hemolytic anemia causes increased heme metabolism; exception: infants where gut flora has not developed).

Serum: increased unconjugated bilirubin.

Kernicterus is associated with increased unconjugated bilirubin.

Hepatocellular

Hepatocellular (hepatic) jaundice can be caused by acute or chronic hepatitis, hepatotoxicity, cirrhosis, drug induced hepatitis and alcoholic liver disease. Cell necrosis reduces the liver's ability to metabolize and excrete bilirubin leading to a buildup of unconjugated bilirubin in the blood. Other causes include primary biliary cirrhosis leading to an increase in plasma conjugated bilirubin because there is impairment of excretion of conjugated bilirubin into the bile. The blood contains abnormally raised amount of conjugated bilirubin and bile salts which are excreted in the urine. Jaundice seen in the newborn, known as neonatal jaundice, is common in newborns [6] as hepatic machinery for the conjugation and excretion of bilirubin does not fully mature until approximately two weeks of age. Rat fever (leptospirosis) can also cause hepatic jaundice. In hepatic jaundice, there is invariably cholestasis.

Laboratory findings depend on the cause of jaundice.

Urine: Conjugated bilirubin present, urobilirubin > 2 units but variable (except in children).

Kernicterus is a condition not associated with increased conjugated bilirubin.

Plasma protein show characteristic changes.

Plasma albumin level is low but plasma globulins are raised due to an increased formation of antibodies.

Bilirubin transport across the hepatocyte may be impaired at any point between the uptake of unconjugated bilirubin into the cell and transport of conjugated bilirubin into biliary canaliculi. In addition, swelling of cells and oedema due to inflammation cause mechanical obstruction of intrahepatic biliary tree. Hence in hepatocellular jaundice, concentration of both unconjugated and conjugated bilirubin rises in the blood. In hepatocellular disease, there is usually interference in all major steps of bilirubin metabolism - uptake, conjugation and

5

excretion. However, excretion is the rate-limiting step, and usually impaired to the greatest extent. As a result, conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia predominates.

Post-hepatic

Post-hepatic jaundice, also called obstructive jaundice, is caused by an interruption to the drainage of bile in the biliary system. The most common causes are gallstones in the common bile duct, and pancreatic cancer in the head of the pancreas. Also, a group of parasites known as

"liver flukes" can live in the common bile duct, causing obstructive jaundice. Other causes include strictures of the common bile duct, biliary atresia, cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatitis and pancreatic pseudocysts. A rare cause of obstructive jaundice is Mirizzi's syndrome.

In complete obstruction of the bile duct, no urobilinogen is found in the urine, since bilirubin has no access to the intestine and it is in the intestine that bilirubin gets converted to urobilinogen to be later released into the general circulation. In this case, presence of bilirubin (conjugated) in the urine without urine-urobilinogen suggests obstructive jaundice, either intra-hepatic or posthepatic.

The presence of pale stools and dark urine suggests an obstructive or post-hepatic cause as normal feces get their color from bile pigments. However, although pale stools and dark urine are a feature of biliary obstruction, they can occur in many intra-hepatic illnesses and are therefore not a reliable clinical feature to distinguish obstruction from hepatic causes of jaundice.

Patients also can present with elevated serum cholesterol, and often complain of severe itching or

"pruritus" because of the deposition of bile salts.

No single test can differentiate between various classifications of jaundice. A combination of liver function tests is essential to arrive at a diagnosis.

Table of diagnostic tests

Function test

Total bilirubin

Pre-hepatic

Jaundice

Normal /

Increased

Hepatic Jaundice

Increased

Post-hepatic

Jaundice

Conjugated bilirubin Increased Increased

Unconjugated bilirubin

Urobilinogen

Urine Color

Normal

Normal /

Increased

Normal /

Increased

Normal

Normal

Increased

Increased

Dark (urobilinogen + conjugated bilirubin)

Normal

Decreased /

Negative

Dark (conjugated bilirubin)

Pale Stool Color

Alkaline phosphatase levels

Alanine transferase and

Aspartate transferase levels

Normal

Increased

Increased

Conjugated Bilirubin in Urine Not Present Present

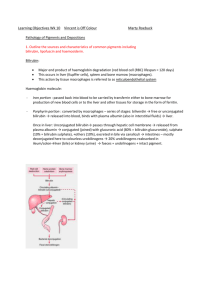

Pathophysiology

In order to understand how jaundice results, the pathological processes that cause jaundice to take their effect must be understood. Jaundice itself is not a disease, but rather a sign of one of many possible underlying pathological processes that occur at some point along the normal physiological pathway of the metabolism of bilirubin.

When red blood cells have completed their life span of approximately 120 days, or when they are damaged, their membranes become fragile and prone to rupture. As each red blood cell traverses through the reticuloendothelial system, its cell membrane ruptures when its membrane is fragile enough to allow this. Cellular contents, including hemoglobin, are subsequently released into the blood. The hemoglobin is phagocytosed by macrophages, and split into its heme and globin

6

portions. The globin portion, a protein, is degraded into amino acids and plays no role in jaundice. Two reactions then take place with the heme molecule. The first oxidation reaction is catalyzed by the microsomal enzyme heme oxygenase and results in biliverdin (green color pigment), iron and carbon monoxide. The next step is the reduction of biliverdin to a yellow color tetrapyrol pigment called bilirubin by cytosolic enzyme biliverdin reductase. This bilirubin is "unconjugated," "free" or "indirect" bilirubin. Approximately 4 mg of bilirubin per kg of blood is produced each day. The majority of this bilirubin comes from the breakdown of heme from expired red blood cells in the process just described. However approximately 20 percent comes from other heme sources, including ineffective erythropoiesis, and the breakdown of other hemecontaining proteins, such as muscle myoglobin and cytochromes.

Hepatic events

The unconjugated bilirubin then travels to the liver through the bloodstream. Because this bilirubin is not soluble, however, it is transported through the blood bound to serum albumin.

Once it arrives at the liver, it is conjugated with glucuronic acid (to form bilirubin diglucuronide, or just "conjugated bilirubin") to become more water soluble. The reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme UDP-glucuronyl transferase.

This conjugated bilirubin is excreted from the liver into the biliary and cystic ducts as part of bile. Intestinal bacteria convert the bilirubin into urobilinogen. From here the urobilinogen can take two pathways. It can either be further converted into stercobilinogen, which is then oxidized to stercobilin and passed out in the feces, or it can be reabsorbed by the intestinal cells, transported in the blood to the kidneys, and passed out in the urine as the oxidised product urobilin. Stercobilin and urobilin are the products responsible for the coloration of feces and urine, respectively.

Thalassemia (British English: thalassaemia) is a group of inherited autosomal recessive blood disorders that originated in the Mediterranean region. In thalassemia the genetic defect, which could be either mutation or deletion, results in reduced rate of synthesis or no synthesis of one of the globin chains that make up hemoglobin. This can cause the formation of abnormal hemoglobin molecules, thus causing anemia, the characteristic presenting symptom of the thalassemias.

Thalassemia is a quantitative problem of too few globins synthesized, whereas sickle-cell disease

(a hemoglobinopathy) is a qualitative problem of synthesis of an incorrectly functioning globin.

Thalassemias usually result in underproduction of normal globin proteins, often through mutations in regulatory genes. Hemoglobinopathies imply structural abnormalities in the globin proteins themselves. The two conditions may overlap, however, since some conditions that cause abnormalities in globin proteins (hemoglobinopathy) also affect their production (thalassemia).

Thus, some thalassemias are hemoglobinopathies, but most are not. Either or both of these conditions may cause anemia.

The two major forms of the disease, alpha- and beta- (see below), are prevalent in discrete geographical clusters around the world - it is presumed associated with malarial endemicity in ancient times. Alpha is prevalent in peoples of Western African and South Asian descent. It is nowadays found in populations living in Africa and in the Americas. It is also found in Tharu in the Terai region of Nepal and India. It is believed to account for much lower malaria morbidity and mortality, accounting for the historic ability of Tharus to survive in heavily malarial areas where others could not.

Beta thalassemia is particularly prevalent among Mediterranean peoples, and this geographical association is responsible for its naming: Thalassa is Greek for the sea, Haema is

Greek for blood. In Europe, the highest concentrations of the disease are found in Greece, coastal regions in Turkey, in particular, Aegean Region such as Izmir, Balikesir, Aydin, Mugla, and

Mediterranean Region such as Antalya, Adana, Mersin, in parts of Italy, in particular, Southern

Italy and the lower Po valley. The major Mediterranean islands (except the Balearics) such as

Sicily, Sardinia, Malta, Corsica, Cyprus, and Crete are heavily affected in particular. Other

Mediterranean people, as well as those in the vicinity of the Mediterranean, also have high rates

7

of thalassemia, including people from West Asia and North Africa. Far from the Mediterranean,

South Asians are also affected, with the world's highest concentration of carriers (16% of the population) being in the Maldives.

The thalassemia trait may confer a degree of protection against malaria, which is or was prevalent in the regions where the trait is common, thus conferring a selective survival advantage on carriers (known as heterozygous advantage), and perpetuating the mutation. In that respect, the various thalassemias resemble another genetic disorder affecting hemoglobin, sickle-cell disease.

Dubin–Johnson syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder that causes an increase of conjugated bilirubin in the serum without elevation of liver enzymes (ALT, AST). This condition is associated with a defect in the ability of hepatocytes to secrete conjugated bilirubin into the bile, and is similar to Rotor syndrome. It is usually asymptomatic but may be diagnosed in early infancy based on laboratory tests.

The conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is a result of defective endogenous and exogenous transfer of anionic conjugates from hepatocytes into the bile. Impaired biliary excretion of bilirubin glucuronides is due to a mutation in the canalicular multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2).

Pigment deposition in lysosomes causes the liver to turn black.

Rotor syndrome, also called Rotor type hyperbilirubinemia, is a rare, relatively benign autosomal recessive bilirubin disorder of unknown origin. It is a distinct disorder, yet similar to

Dubin-Johnson syndrome — both diseases cause an increase in conjugated bilirubin. Rotor syndrome has many things in common with Dubin-Johnson syndrome, an exception being that the liver cells are not pigmented. The main symptom is a non-itching jaundice. There is a rise in bilirubin in the patient's serum, mainly of the conjugated type. Rotor syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. This means the defective gene responsible for the disorder is on an autosome, and two copies of the defective gene (one inherited from each parent) are required to be born with the disorder. The parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder both carry one copy of the defective gene but usually do not experience any signs or symptoms of the disorder.

Crigler-Najjar Syndrome or CNS is a rare disorder affecting the metabolism of bilirubin, a chemical formed from the breakdown of blood. The disorder results in an inherited form of non-hemolytic jaundice, which results in high levels of unconjugated bilirubin and often leads to brain damage in infants.

This syndrome is divided into type I and type II, with the latter sometimes called Arias syndrome. These two types, along with Gilbert's syndrome, Dubin-Johnson syndrome, and Rotor syndrome, make up the five known hereditary defects in bilirubin metabolism. Unlike Gilbert's syndrome, only a few hundred cases of CNS are known.

Infectious mononucleosis (IM; also known as EBV infectious mononucleosis, Pfeifer's disease, Filatov's disease and sometimes colloquially as the kissing disease from its oral transmission or simply as mono in North America and as glandular fever in other Englishspeaking countries) is an infectious, widespread viral disease caused by the Epstein–Barr virus

(EBV), one type of herpes virus, to which more than 90% of adults have been exposed.

Occasionally, the symptoms can recur at a later period. Most people are exposed to the virus as children, when the disease produces no noticeable or only flu-like symptoms. In developing countries, people are exposed to the virus in early childhood more often than in developed countries. As a result, the disease in its observable form is more common in developed countries.

It is most common among adolescents and young adults.

Especially in adolescents and young adults, the disease is characterized by fever, sore throat and fatigue, along with several other possible signs and symptoms. It is primarily diagnosed by observation of symptoms, but suspicion can be confirmed by several diagnostic tests.

Common signs include lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes), splenomegaly (enlarged spleen), hepatitis (refers to inflammation of hepatocytes—cells in the liver) and hemolysis (the bursting of red blood cells). Older adults are less likely to have a sore throat or

8

lymphadenopathy, but are instead more likely to present with hepatomegaly (enlargement of the liver) and jaundice. Rarer signs and symptoms include thrombocytopenia (lower levels of platelets), with or without pancytopenia (lower levels of all types of blood cells), splenic rupture, splenic hemorrhage, upper airway obstruction, pericarditis and pneumonitis. Another rare manifestation of mononucleosis is erythema multiforme.

Hepatitis A (formerly known as infectious hepatitis and epidemical virus) is an acute infectious disease of the liver caused by the hepatitis A virus (Hep A), an RNA virus, usually spread the fecal-oral route; transmitted person-to-person by ingestion of contaminated food or water or through direct contact with an infectious person. Tens of millions of individuals worldwide are estimated to become infected with Hep A each year. The time between infection and the appearance of the symptoms (the incubation period) is between two and six weeks and the average incubation period is 28 days.

In developing countries, and in regions with poor hygiene standards, the incidence of infection with this virus is high and the illness is usually contracted in early childhood. As incomes rise and access to clean water increases, the incidence of HAV decreases. Hepatitis A infection causes no clinical signs and symptoms in over 90% of infected children and since the infection confers lifelong immunity, the disease is of no special significance to those infected early in life.

In Europe, the United States and other industrialized countries, on the other hand, the infection is contracted primarily by susceptible young adults, most of whom are infected with the virus during trips to countries with a high incidence of the disease or through contact with infectious persons.

HAV infection produces a self-limited disease that does not result in chronic infection or chronic liver disease. However, 10–15% of patients might experience a relapse of symptoms during the 6 months after acute illness. Acute liver failure from Hepatitis A is rare (overall casefatality rate: 0.5%). The risk for symptomatic infection is directly related to age, with >80% of adults having symptoms compatible with acute viral hepatitis and the majority of children having either asymptomatic or unrecognized infection. Antibody produced in response to HAV infection persists for life and confers protection against reinfection. The disease can be prevented by vaccination, and hepatitis A vaccine has been proven effective in controlling outbreaks worldwide.

Hepatitis B is an infectious inflammatory illness of the liver caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) that affects hominoidea, including humans. Originally known as "serum hepatitis", the disease has caused epidemics in parts of Asia and Africa, and it is endemic in China. About a third of the world population has been infected at one point in their lives, including 350 million who are chronic carriers.

The virus is transmitted by exposure to infectious blood or body fluids such as semen and vaginal fluids, while viral DNA has been detected in the saliva, tears, and urine of chronic carriers. Perinatal infection is a major route of infection in endemic (mainly developing) countries. Other risk factors for developing HBV infection include working in a healthcare setting, transfusions, and dialysis, acupuncture, tattooing, extended overseas travel and residence in an institution. However, Hepatitis B viruses cannot be spread by holding hands, sharing eating utensils or drinking glasses, kissing, hugging, coughing, sneezing, or breastfeeding.

The acute illness causes liver inflammation, vomiting, jaundice and, rarely, death. Chronic hepatitis B may eventually cause cirrhosis and liver cancer—a disease with poor response to all but a few current therapies. The infection is preventable by vaccination.

Hepatitis B virus is an hepadnavirus—hepa from hepatotropic (attracted to the liver) and dna because it is a DNA virus—and it has a circular genome of partially double-stranded DNA. The viruses replicate through an RNA intermediate form by reverse transcription, which practice relates them to retroviruses. Although replication takes place in the liver, the virus spreads to the blood where viral proteins and antibodies against them are found in infected people.

9

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease affecting primarily the liver, caused by the hepatitis

C virus (HCV). The infection is often asymptomatic, but chronic infection can lead to scarring of the liver and ultimately to cirrhosis, which is generally apparent after many years. In some cases, those with cirrhosis will go on to develop liver failure, liver cancer or life-threatening esophageal and gastric varices.

HCV is spread primarily by blood-to-blood contact associated with intravenous drug use, poorly sterilized medical equipment and transfusions. An estimated 130–170 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C. The existence of hepatitis C (originally "non-A non-B hepatitis") was postulated in the 1970s and proven in 1989. It is not known to cause disease in other animals.

The virus persists in the liver in about 85% of those infected. This persistent infection can be treated with medication: a combination of peginterferon and ribavirin are the current standard therapy. Overall, 50–80% of people treated are cured. Those who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer may require a liver transplant. Hepatitis C is the leading cause of liver transplantation though the virus usually recurs after transplantation. No vaccine against hepatitis C is currently available.

Hepatitis D, also referred to as hepatitis D virus (HDV) and classified as Hepatitis delta virus, is a disease caused by a small circular enveloped RNA virus. It is one of five known hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D, and E. HDV is considered to be a subviral satellite because it can propagate only in the presence of the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Transmission of HDV can occur either via simultaneous infection with HBV (coinfection) or superimposed on chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis B carrier state (superinfection).

Both superinfection and coinfection with HDV results in more severe complications compared to infection with HBV alone. These complications include a greater likelihood of experiencing liver failure in acute infections and a rapid progression to liver cirrhosis, with an increased chance of developing liver cancer in chronic infections. In combination with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis D has the highest mortality rate of all the hepatitis infections of 20%.

Hepatitis E is a viral hepatitis (liver inflammation) caused by infection with a virus called hepatitis E virus (HEV). HEV is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA icosahedral virus with a 7.5 kilobase genome. HEV has a fecal-oral transmission route. It is one of five known hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D, and E. Infection with this virus was first documented in 1955 during an outbreak in New Delhi, India.

Hepatotoxicity (from hepatic toxicity) implies chemical-driven liver damage.

The liver plays a central role in transforming and clearing chemicals and is susceptible to the toxicity from these agents. Certain medicinal agents, when taken in overdoses and sometimes even when introduced within therapeutic ranges, may injure the organ. Other chemical agents, such as those used in laboratories and industries, natural chemicals (e.g., microcystins) and herbal remedies can also induce hepatotoxicity. Chemicals that cause liver injury are called hepatotoxins.

More than 900 drugs have been implicated in causing liver injury and it is the most common reason for a drug to be withdrawn from the market. Chemicals often cause subclinical injury to liver which manifests only as abnormal liver enzyme tests. Drug-induced liver injury is responsible for 5% of all hospital admissions and 50% of all acute liver failures.

Adverse drug reactions are classified as type A (intrinsic or pharmacological) or type B

(idiosyncratic). Type A drug reaction accounts for 80% of all toxicities.

Drugs or toxins that have a pharmacological (type A) hepatotoxicity are those that have predictable dose-response curves (higher concentrations cause more liver damage) and well characterized mechanisms of toxicity, such as directly damaging liver tissue or blocking a metabolic process. As in the case of acetaminophen overdose, this type of injury occurs shortly after some threshold for toxicity is reached. Idiosyncratic (type B) injury occurs without warning, when agents cause non-predictable hepatotoxicity in susceptible individuals which is not related to dose and has a variable latency period. This type of injury does not have a clear

10

dose-response nor temporal relationship, and most often does not have predictive models.

Idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity has led to the withdrawal of several drugs from market even after rigorous clinical testing as part of the FDA approval process; Troglitazone (Rezulin) and trovafloxacin (Trovan) are two prime examples of idiosyncratic hepatotoxins pulled from market.

When used orally, ketoconazole has been associated with hepatic toxicity, including some fatalities.

Heliotropium – is a genus of flowering plants in the borage family, Boraginaceae. There are 250 to 300 species in this genus, which are commonly known as heliotropes. Several heliotropes are popular garden plants, most notably Garden Heliotrope (H. arborescens). Some species are weeds and many are hepatotoxic if eaten in large quantities due to abundant pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Danainae butterflies like to visit these plants, as pyrrolizidine alkaloids produce a kind of "perfume" to attract mates.

A gallstone is a crystalline concretion formed within the gallbladder by accretion of bile components. These calculi are formed in the gallbladder, but may pass distally into other parts of the biliary tract such as the cystic duct, common bile duct, pancreatic duct, or the ampulla of

Vater.

Presence of gallstones in the gallbladder may lead to acute cholecystitis, an inflammatory condition characterized by retention of bile in the gallbladder and often secondary infection by intestinal microorganisms, predominantly Escherichia coli and Bacteroides species. Presence of gallstones in other parts of the biliary tract can cause obstruction of the bile ducts, which can lead to serious conditions such as ascending cholangitis or pancreatitis. Either of these two conditions can be life-threatening, and are therefore considered to be medical emergencies.

Gallstones may be asymptomatic, even for years. These gallstones are called "silent stones" and do not require treatment. Symptoms commonly begin to appear once the stones reach a certain size (>8 mm). A characteristic symptom of gallstones is a "gallstone attack", in which a person may experience intense pain in the upper-right side of the abdomen, often accompanied by nausea and vomiting, that steadily increases for approximately 30 minutes to several hours. A patient may also experience referred pain between the shoulder blades or below the right shoulder. These symptoms may resemble those of a "kidney stone attack". Often, attacks occur after a particularly fatty meal and almost always happen at night. Other symptoms include abdominal bloating, intolerance of fatty foods, belching, gas, and indigestion.

Pancreatic cancer refers to a malignant neoplasm originating from transformed cells arising in tissues forming the pancreas. The most common type of pancreatic cancer, accounting for 95% of these tumors, is adenocarcinoma (tumors exhibiting glandular architecture on light microscopy) arising within the exocrine component of the pancreas. A minority arise from islet cells, and are classified as neuroendocrine tumors. The symptoms that lead to diagnosis depend on the location, the size, and the tissue type of the tumor. They may include abdominal pain and jaundice (if the tumor compresses the bile duct).

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth most common cause of cancer-related deaths across the globe.

Pancreatic cancer often has a poor prognosis: for all stages combined, the 1- and 5-year relative survival rates are 25% and 6%, respectively; for local disease the 5-year survival is approximately 20% while the median survival for locally advanced and for metastatic disease, which collectively represent over 80% of individuals, is about 10 and 6 months respectively.

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is a Gram-negative bacterium that causes Pseudotuberculosis

(Yersinia) disease in animals; humans occasionally get infected zoonotically, most often through the food-borne route. It is urease positve. In animals, Y. pseudotuberculosis can cause tuberculosis-like symptoms, including localized tissue necrosis and granulomas in the spleen, liver, and lymph node. In humans, symptoms of Pseudotuberculosis (Yersinia) are similar to those of infection with Yersinia enterocolitica (fever and right-sided abdominal pain), except that the diarrheal component is often absent, which sometimes makes the resulting condition difficult to diagnose. Y. pseudotuberculosis infections can mimic appendicitis, especially in children and

11

younger adults, and, in rare cases, the disease may cause skin complaints (erythema nodosum), joint stiffness and pain (reactive arthritis), or spread of bacteria to the blood (bacteremia).

Pseudotuberculosis (Yersinia) usually becomes apparent 5–10 days after exposure and typically lasts 1–3 weeks without treatment. In complex cases or those involving immunocompromised patients, antibiotics may be necessary for resolution; ampicillin, aminoglycosides, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, or a cephalosporin may all be effective.

The recently described syndrome Izumi-fever has been linked to infection with

Y.pseudotuberculosis.

The symptoms of fever and abdominal pain mimicking appendicitis (actually from mesenteric lymphadenitis) associated with Y. pseudotuberculosis infection are not typical of the diarrhea and vomiting from classical food poisoning incidents. Although Y. pseudotuberculosis is usually only able to colonize hosts by peripheral routes and cause serious disease in immunocompromised individuals, if this bacterium gains access to the blood stream, it has an

LD50 comparable to Y. pestis at only 10CFU.

Yersinia enterocolitica is a species of gram-negative coccobacillus-shaped bacterium, belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. Yersinia enterocolitica infection causes the disease yersiniosis, which is a zoonotic disease occurring in humans as well as a wide array of animals such as cattle, deer, pigs, and birds. Many of these animals recover from the disease and become asymptomatic carriers.

Acute Y. enterocolitica infections usually lead to mild self-limiting enterocolitis or terminal ileitis in humans. Symptoms may include watery or bloody diarrhea and fever. After oral uptake yersiniae replicate in the terminal ileum and invade Peyer's patches. From here yersiniae can disseminate further to mesenteric lymph nodes causing lymphadenopathy. This condition can be confused with appendicitis and is therefore called pseudoappendicitis. In immunosuppressed individuals, yersiniae can disseminate from the gut to liver and spleen and form abscesses. Because Yersinia is a siderophilic (iron-loving) bacteria, people with hereditary hemochromatosis (a disease resulting in high body iron levels) are more susceptible to infection with Yersinia (and other siderophilic bacteria). In fact, the most common contaminant of stored blood is Y. enterocolitica. See yersiniosis for further details. Yersiniae are usually transmitted to humans by insufficiently cooked pork or contaminated water.

Sepsis is a potentially deadly medical condition that is characterized by a whole-body inflammatory state (called a systemic inflammatory response syndrome or SIRS) and the presence of a known or suspected infection. The body may develop this inflammatory response by the immune system to microbes in the blood, urine, lungs, skin, or other tissues. A lay term for sepsis is blood poisoning, also used to describe septicaemia. Severe sepsis is the systemic inflammatory response, infection and the presence of organ dysfunction. Severe sepsis is usually treated in the intensive care unit with intravenous fluids and antibiotics. If fluid replacement isn't sufficient to maintain blood pressure, specific vasopressor medications can be used. Mechanical ventilation and dialysis may be needed to support the function of the lungs and kidneys, respectively. To guide therapy, a central venous catheter and an arterial catheter may be placed; measurement of other hemodynamic variables (such as cardiac output, or mixed venous oxygen saturation) may also be used. Sepsis patients require preventive measures for deep vein thrombosis, stress ulcers and pressure ulcers, unless other conditions prevent this. Some patients might benefit from tight control of blood sugar levels with insulin (targeting stress hyperglycemia), or low-dose corticosteroids. Activated drotrecogin alfa (recombinant protein C) has not been found to be helpful, and has recently been withdrawn from sale.

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. The virus is a 40 to 50 nm enveloped

RNA virus with positive sense of the Flaviviridae family.

The yellow fever virus is transmitted by the bite of female mosquitoes (the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti, and other species) and is found in tropical and subtropical areas in

South America and Africa, but not in Asia. The only known hosts of the virus are primates and several species of mosquito. The origin of the disease is most likely to be Africa, from where it

12

was introduced to South America through the slave trade in the 16th century. Since the 17th century, several major epidemics of the disease have been recorded in the Americas, Africa and

Europe. In the 19th century, yellow fever was deemed one of the most dangerous infectious diseases.

Yellow fever presents in most cases with fever, nausea, and pain, and it generally subsides after several days. In some patients, a toxic phase follows, in which liver damage with jaundice (inspiring the name of the disease) can occur and lead to death. Because of the increased bleeding tendency (bleeding diathesis), yellow fever belongs to the group of hemorrhagic fevers. The WHO estimates that yellow fever causes 200,000 illnesses and 30,000 deaths every year in unvaccinated populations; today nearly 90% of the infections occur in

Africa.

A safe and effective vaccine against yellow fever has existed since the middle of the 20th century, and some countries require vaccinations for travelers. Since no therapy is known, vaccination programs are of great importance in affected areas, along with measures to prevent bites and reduce the population of the transmitting mosquito. Since the 1980s, the number of cases of yellow fever has been increasing, making it a reemerging disease. This is likely due to warfare and social disruption in several African nations.

Leptospirosis (also known as Weil's syndrome, canicola fever, canefield fever, nanukayami fever, 7-day fever, Rat Catcher's Yellows, Fort Bragg fever, black jaundice and

Pretibial fever is caused by infection with bacteria of the genus Leptospira, and affects humans as well as other mammals, birds, amphibians, and reptiles.

The disease was first described by Adolf Weil in 1886 when he reported an "acute infectious disease with enlargement of spleen, jaundice, and nephritis." Leptospira was first observed in

1907 from a post mortem renal tissue slice. In 1908, Inada and Ito first identified it as the causative organism and in 1916 noted its presence in rats.

Though recognised among the world's most common diseases transmitted to people from animals, leptospirosis is nonetheless a relatively rare bacterial infection in humans. The infection is commonly transmitted to humans by allowing water that has been contaminated by animal urine to come in contact with unhealed breaks in the skin, the eyes, or with the mucous membranes. Outside of tropical areas, leptospirosis cases have a relatively distinct seasonality with most of them occurring in spring and autumn.

Amoebiasis, or Amebiasis, refers to infection caused by the amoeba Entamoeba histolytica. The term Entamoebiasis is occasionally seen but is no longer in use; it refers to the same infection. Likewise amoebiasis is sometimes incorrectly used to refer to infection with other amoebae, but strictly speaking it should be reserved for Entamoeba histolytica infection. A gastrointestinal infection that may or may not be symptomatic and can remain latent in an infected person for several years, amoebiasis is estimated to cause 70,000 deaths per year worldwide. Symptoms can range from mild diarrhea to dysentery with blood and mucus in the stool. E. histolytica is usually a commensal organism. Severe amoebiasis infections (known as invasive or fulminant amoebiasis) occur in two major forms. Invasion of the intestinal lining causes amoebic dysentery or amoebic colitis. If the parasite reaches the bloodstream it can spread through the body, most frequently ending up in the liver where it causes amoebic liver abscesses. Liver abscesses can occur without previous development of amoebic dysentery. When no symptoms are present, the infected individual is still a carrier, able to spread the parasite to others through poor hygienic practices. While symptoms at onset can be similar to bacillary dysentery, amoebiasis is not bacteriological in origin and treatments differ, although both infections can be prevented by good sanitary practices.

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of

Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases progressing to coma or death. It is widespread in tropical and subtropical regions, including much of Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

13

Five species of Plasmodium can infect and be transmitted by humans. Severe disease is largely caused by P. falciparum while the disease caused by P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae is generally a milder disease that is rarely fatal. P. knowlesi is a zoonotic species that causes malaria in macaques but can also infect humans. Malaria transmission can be reduced by preventing mosquito bites by distribution of mosquito nets and insect repellents, or by mosquitocontrol measures such as spraying insecticides and draining standing water (where mosquitoes breed).

Despite a clear need, no vaccine offering a high level of protection currently exists.

Efforts to develop one are ongoing. A number of medications are available to prevent malaria in travelers to malaria-endemic countries (prophylaxis). A variety of antimalarial medications are available. Severe malaria is treated with intravenous or intramuscular quinine or, since the mid-

2000s, the artemisinin derivative artesunate, which is superior to quinine in both children and adults. Resistance has developed to several antimalarial drugs, most notably chloroquine and artemisinin.

6.2. The analytical part of

Situational problems

Objective number one. The patient, aged 20, went to a doctor on the 5th day of illness.

The patient is concerned about the increase in temperature from the 1st day of illness, weakness, fatigue, sore throat, and cough. The patient is independently taking aspirin, analgin. Against this background, on the 4th day of illness there was heaviness in the epigastrium, nausea, sudden loss of appetite, dark urine.

OBJECTIVE: patient lethargic, pale, mild jaundice sclera and mucous membranes of the mouth. Liver palpable 1 cm below the costal arch.Pulse 64 beats per minute, blood pressure -

100/60 mmHg He lives in a dormitory room with 4 people.

1.Place a provisional diagnosis.

2. The tactics of the SPM.

№ Number of Replies

1. CAA Acute icteric form in moderate pace

2. Refer the patient to a hospital infection.

Problem number 2.

Patient K., 64 years old, was admitted to the hospital on the 16th day of illness with complaints of fatigue, poor sleep, decreased appetite, nause1.The disease developed gradually with malaise, increasing weakness, loss of appetite, dull pain in right hypochondrium and mild nause1.At the 12-day notice dark urine, and icteric sclera color, itching of the skin.

OBJECTIVE: adinamichen sick, lethargic, jaundiced sclera and expressed in the skin, the skin and injection site bruising, neck and chest unit urticarial elements. Pulse 58 beats per minute, satisfactory filling. Cardiac sounds are muffled. BP 95/65 mm HgTongue coated, wet. The abdomen is moderately distended, soft. Liver 1.0 2.0 2.5 cm, flexible and sensitive. Spleen 0.5 cm, b / w. The urine is dark, discolored feces. The total bilirubin - 125 micromol / L, direct - 80 mmol / l, indirect - 40 micromol / L, ALT - 4.2 mmol / ml / h, AST -

1.2 mmol / mL / h; thymol test - 14 units, sulemovaya sample - 1.5 ml, prothrombin index -

60%. Anamnesis revealed that 4 months before the disease the patient underwent abdominal surgery and received blood transfusions.

1. Place a provisional diagnosis

2. The tactics of the SPM.

3. What additional methods should be made for placing a clinical diagnosis?

14

№ Number of Replies

1.

HBV.

2. Refer the patient to a hospital infection.

3. Need a blood test for HBsAg and for markers of HBV.

Problem number 3.

Patient K., aged 15, fell ill with acute, 3 days the temperature is kept at 39,5 ° C. Sore throat, tightness in the right upper quadrant pain in large joints.

On examination, the patient lethargic, pale skin, sclera icteric, there is an increase of the neck, lymph nodes zadnesheynyh the size of almonds, slightly painful. Language dryish, overlaid with a touch of dirty, swollen throat, tonsils, enlarged to belosovato-yellow coating, which can be easily removed with a spatula, palpation of the liver is increased by 2.0 cm, 4.0 cm in the spleen, the general analysis of blood leukocytes 15.0 * 109 / L, left shift, monocytosis - 22%, atypical mononuclear cells - 12%, ESR - 30 mm / h

1. Your preliminary diagnosis?

2. The tactics of the SPM.

№ Number of Replies

1. Infectious mononucleosis.

2. Refer the patient to a hospital infection.

6.3. The practical part

Determination of bile pigments in the urine of patients with icteric syndrome (sample

Rosina).

Objective: To determine the bile pigments in urine, bilirubin under the action of an oxidizing agent iodine, is converted into green biliverdin.

Indications: Acute and chronic viral hepatitis.

Required equipment: test tubes, pipettes, sterile gloves, tripod, 1% alcoholic solution of iodine.

Running steps (steps):

№ Event Not finished

Partially completed executed correctly (10

(5 points)

0

(5 points)

5 points)

10 1. Wear rubber gloves, sterile

2. In a clean container to collect urine 0 5 10

3.

4.

5.

7.

The left hand is taken clean tube

Pour 4-5 ml of urine of the patient in a test tube

Put them in a test tube with the urine in a tripod

6. The right hand is taken pipette and gain 1% alcoholic solution of iodine

7. On the wall of the tube with a pipette to add a few drops of 1% alcoholic solution of iodine

8. Wait 10-15 seconds

0

0

0

0

0

0

5

5

5

5

5

5

10

10

10

10

10

10

15

9. When a positive sample at the boundary of the liquid formed a green ring

10. As the intensity of the green belt are distinguished weakly, moderately and strongly positive response

0

0

5

5

10

10

Total 0 50 100

7. Test questions

1. What are Clinical and laboratory features of jaundice in viral hepatitis?

2.What are Clinical and laboratory features of jaundice in bacterial and viral infections?

3. What are Principles of preparation of a diagnostic algorithm for finding the presence of

jaundice syndrome in a patient?

4. What are the tactics of a general practitioner in identifying patients with the syndrome

of jaundice?

5. What is current pathogenetic and antiviral therapy of viral hepatitis, clinical

examination and rehabilitation of patients with viral hepatitis?

8. The recommended literature

1.Zubik TM, Ivanov KS, Kazantsev AP, Foresters, AL Differential diagnosis of infectious diseases. Leningrad, 1991.

2.VS Vasil'ev, Komar, VI, VM Tsyrkunov The practice of infectious diseases. Minsk, 1994.

3. Kazantsev AP, Zubik TM, KS Ivanov, VA Kazantsev Differential diagnosis of infectious diseases. Moscow, 1999.

4. Emond, R., Rowland H., F. Uelsbi Infectious Diseases. Color Atlas. Moscow, 1998.

5. Madzhidov VM Yukumli kasalliklar. Tashkent, 1992.

6. Makhmudov OS Bolalar yukumli kasalliklari. Tashkent, 1995.

7. Uchaikin WR Guidelines for Communicable Diseases in children. Moscow, 1999.

Eight. Shuvalov, EP Infectious diseases. Moscow, 1999.

9. Musabayev IK "Guide to intestinal infections." Tashkent, 1982.

10. Pokrovsky VI, Pak SG et al, "Infectious disease and epidemiology." Moscow, 2003.

11. Yushchuk ND, Vengerov YY "Lectures on infectious diseases." Moscow, 1999.

12. Uchaikin VF "Guidelines for infectious diseases in children." Moscow, 1998.

13. Online Resources (www.medlinks.ru, www.cdc.gov, ...).

16