moving to renewables - Royal Economic Society

advertisement

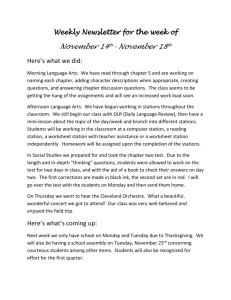

MOVING TO RENEWABLES: WIND POWER COSTS COULD BE PASSED ON IN HIGHER ENERGY PRICES Energy prices are likely to rise if the UK is to reach its renewable energy targets for 2020. That is one of the findings of new research by Professor Richard Green and Dr Nicholas Vasilakos, presented at the Royal Economic Society’s 2011 annual conference, which analyses the likely effects of changes to the UK energy industry if it is to build the 30GW of wind power stations needed to meet the country’s targets. The study shows that these new wind farms will also increase the need for generating companies to build flexible power stations and will reduce demand for low-carbon baseload solutions such as nuclear power. While this might not change electricity wholesale prices, it will cause retail prices to rise if the low-carbon generators need extra support to cover their costs. The authors argue that the government’s plans for reforming the electricity market need to ensure that investment in the flexible power stations remains attractive: ‘Most of the attention so far has been given to support for renewable and nuclear generators, which are mostly inflexible. The current market arrangements may be inadequate to support such a large amount of infrequently used plant.’ ‘A capacity market, one of the options being considered by the government, would reduce these risks.’ More… Building a large number of wind farms to meet the UK’s targets for renewable energy will have significant effects on the rest of the electricity industry. Generating companies will need more flexible power stations, which may not run very often, and will have less scope to build low-carbon baseload stations such as nuclear. If they adjust the capacity that they own in this way, the pattern and level of electricity wholesale prices may not change much in response to the shift towards renewable energy – but retail prices will rise if the low-carbon generators need extra support to cover their costs. The government’s Electricity Market Reform process needs to ensure that investment in the flexible power stations remains attractive – most of the attention so far has been given to the support for (mostly inflexible) renewable and nuclear generators. Professor Richard Green of the University of Birmingham and Dr Nicholas Vasilakos of the University of East Anglia have modelled the output patterns that we might see if we built 30 GW of wind power stations, the level needed to hit the UK’s renewable energy target for 2020. They matched 12 years of wind speed data from the British Atmospheric Data Centre with the demand levels from the same days, again scaled up to forecast levels for 2020. The highest demand that the other stations on the system might have to meet was almost unchanged by the presence of the wind stations – there can be very little wind on the coldest winter days. Most of the time, of course, some or all of the wind stations will be running, and the remaining demand for power will be lower. This means that the number of stations that are needed, but not very often, will increase: compare the right-hand end of the two lines in Figure 1 below. Load-duration curves (2020 with 30 GW wind) GW 60 50 40 30 20 gross demand 10 demand net of wind 0 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 Hours per year Figure 1: The impact of wind power on the demand for electricity Green and Vasilakos modelled what would happen if capacity could perfectly adjust for the new conditions and showed that generators would want to build more flexible Open Cycle Gas Turbine stations, and fewer baseload stations such as nuclear, shown in Figure 2. Equilibrium capacity mix GW 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Wind Open Cycle Gas Turbine Combined Cycle Gas Turbine Nuclear no wind wind Figure 2: The impact of wind power on the desirable capacity mix (specific results depend on the assumptions made, taken from a Redpoint study for DECC) Because the capacity mix is expected to change if we build wind power, the pattern of prices does not change very much, as shown in Figure 3. Each type of power station has to earn enough from the market to cover its costs, unless it gets support from the Renewables Obligation or some other scheme. Price duration curves £/MWh 200 150 wind 100 no wind 50 0 Hours per year -50 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 Figure 3: Price duration curves for the base case (specific results depend on the assumptions made, taken from a Redpoint study for DECC) The key lesson for the Electricity Market Reform is that the UK will need more flexible generators alongside the nuclear and renewable stations that are the main focus of attention, and that investors need to believe that building them will be profitable. The current market arrangements may be inadequate to support such a large amount of infrequently used plant. A capacity market, one of the options being considered by the government, would reduce these risks. ENDS ‘The long-term impact of wind power on electricity prices and generating capacity’ by Richard Green and Nicholas Vasilakos The research was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and the researchers’ other industrial partners, via the Supergen Flexnet Consortium, Grant Number EP/E04011X/1. The views expressed are the authors’ alone. Contact: Richard Green Telephone: 0121 415 8216 Mobile: 07771 940977 Email: r.j.green@bham.ac.uk Or University of Birmingham Press Office, Kate Chapple, 0121 414 2772