Writing Competency - Disability Rights California

advertisement

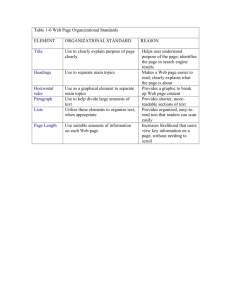

Writing Competency Presented by: California Office of Patients’ Rights Materials adopted from Benchmark Institute “Writing workshop for mentors” 1 Writing Competency General Definition: The ability to control and vary written communications with an audience(s) in a given situation to maximize the accomplishment of objectives. We will explore each of the areas below: 1. Ability to write appropriately to a given audience. 2. Ability to express thoughts in an organized manner. 3. Ability to express a thought with precision, clarity and economy. 4. Ability to use the mechanics of the language -- grammar, punctuation, spelling. 5. Ability to receive and respond to the implicit and explicit communications of others. 6. Ability to write so as to advance immediate and longterm objectives. 2 1. Ability to Write Appropriately to a Given Audience To communicate effectively with an audience is to know that audience -- its concerns, assumptions, expectations and objectives. Advice letters take into account client values just as briefs address decision maker preferences. Since many writings have more than one audience, you also must be able to predict their effects on secondary audiences. Advocates write to people who differ from themselves or the American mainstream in ways that affect how the audience may receive the message; e.g., differences in age, ethnicity, income, language, mental or physical abilities, race, religion or sexual orientation. These differences can make communication even more complex. The ability to accurately assess another's perspective is always limited and requires learning ways to guard against becoming a prisoner of your own preconceptions. Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: • All information that a particular audience needs to understand about a particular event or concept is included. Nothing is included that seems patronizing or offensive. • Issues are stated as simply as possible without compromising meaning. Issues are not made needlessly complicated. If precedents are included, readers understand how they apply to the facts. • Any emotional or interpersonal factors that affect communication are handled appropriately. • Elements of the writing are tailored to its audience(s): -organization -vocabulary, e.g., People First language, non-idiomatic English - grammar - tone - format - style - citation - form - terms of art - medium, e.g., post-it, letter, - memo. 3 2. Ability to Express Thoughts in an Organized Manner Organization means arranging thoughts and connecting ideas in a document and within its individual paragraphs. Sentences must be grouped into paragraphs, and paragraphs linked throughout the document. Transitions act as bridges throughout this structure connecting paragraphs, sentences, clauses, and words helping readers develop and keep a train of thought. Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: • Organizing principles are apparent throughout the writing. Such principles include: - Giving Both Sides (grouped or interspersed throughout a writing) -- pros and cons, assets and liabilities, similarities and differences, hard and easy, bad and good, effective and ineffective, weak and strong, complicated and uncomplicated, controversial and uncontroversial - Chronological -- order of historical events, cause to effect, step-by-step sequence - General to Specific -- general topic to subtopics, theoretical to practical, generalizations to specific examples - IRAC -- Issue, Rule, Application to facts, and Conclusion - Least to Most -- easiest to most difficult, smallest to largest, worst to best, weakest to strongest, least important to most important, least complicated to most complicated, least effective to most effective, least controversial to most controversial - Most to Least -- most important to least important, most persuasive to least persuasive, most known to least known, most factual to least factual (fact to opinion) - Oppositional -- giving a particular argument and showing what's wrong with it. 4 • Selected organizing principles reflect your purpose and the reader's expectations, e.g., most important information is placed in a prominent place. • The lead section (your roadmap) at the beginning of the writing orients the reader to your most important, general idea and directs the reader to the one idea that brings all other ideas and details into focus. It may also describe the way your main idea will be developed. The roadmap shows your destination and helps readers make sense of what follows, e.g., who, what, where, why, and how. • The conclusion at the writing's end shows the reader that you have reached your destination, i.e., done what you set out to do. • Transitions between paragraphs and sentences are coherent. Words and phrases are included that help readers understand how different ideas relate to each other, e.g., exemplify (for example, for instance); affirm (actually, certainly); negate (on the contrary, however); add (moreover, and, also); con-cede (although, granted that); summarize (finally, thus). • Paragraphs are in a logical order and of appropriate length. • Each paragraph is adequately developed with a topic sentence and coherent transitions. The topic sentence focuses and orients the reader on the paragraph's main idea. The topic sentence is strategically placed either at the beginning to alert the reader to how the paragraph is going to develop or at the end to summarize what has been said. • Formatting such as bullets, subheadings or lists are used to emphasize key points. • Pictures, graphs, or tables are used to visually represent meaning. 5 3. Ability to Express a Thought With Precision, Clarity and Economy Short sentences, phrased with concrete words and images, help readers grasp and retain ideas. Readers expect sentences to be structured according to standard English usage rules -- subject, verb and object order. Sentences that defy those rules cause most readers to become weary and quit. Advocacy services staff pay particular care to exercise these skills in writing to its consumers and client community. Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: Sentences • Sentences are short. Most sentences do not exceed 20 words. No sentence expresses more than one complex thought. • Sentences focus on the actor, the action and the object. • Words are arranged with care: most sentences are arranged in subject, verb and object order. • Modifiers -- All describing words or phrases are placed near the words they modify so that the intended meaning is conveyed. The adverb "only" receives particular care because its placement can radically change sentence meaning. • Parallelism - -Grammatically equal sentence elements are used to express two or more matching ideas or items in a series e.g., if one clause uses a verb in the active voice, the other clause should also use the active voice, not the passive voice or a verbal form ending in "-ing." • Effective emphasis is achieved within sentences by moving from old to new, short to long. Ideas already stated, referred to, implied, predictable, less important are expressed at the beginning of a sentence. The least predictable, most important, most significant, the information to be emphasized appear at the end of the sentence. The subject and verb are 6 placed close together at the beginning of the sentence; longer elements are at the end of the sentence. Words • Words are familiar and concrete. • Legalese: Latinisms, pomposities, bureaucratese, jargon, and word gaffes (affect for effect) are not used. Wordiness • Verbose word clusters (the fact that) and compound prepositions (with regard to, prior to, pursuant to) are not used. • Throat clearing -- introductory phases such as "it is interesting to note," "at the outset we must define" -- is not present. • Redundancies (surviving widow, free gift, brown in color) are not present. • Double and multiple negatives are avoided, e.g., a "not unblack dog was chasing a not unsmall rabbit across a not ungreen field." George Orwell Verbs • Generally, active voice is preferred over passive voice except in limited circumstances. In our advocacy approach, we use the passive voice to DMH in order to suggest a change but use our facts to lead them to the reason the change is needed or supported in Code or Regs. • Base verbs are preferred over nouns created from verbs (nominalizations), i.e., she assumed (base verb). She made an assumption (nominalization). • Strong, precise verbs carry the load in sentences. Using is, are, was, were is minimized, unless using the passive voice. 7 4. Ability to Use the Mechanics of the Language Language mechanics guide meaning. Writings that conform to them help the reader understand what you're saying and grasp it more quickly. Spelling errors are usually perceived as reflecting the writer's careless attitude. All mechanical errors undermine writer credibility and can negate sage advice and persuasive argument. Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: Language is used properly including: • Grammar and usage, e.g., - Subject to verb agreement - Pronoun references -- all pronouns clearly refer to definite nouns • Punctuation - Commas are used to: signal nonrestrictive or nonessential material, prevent confusion, and indicate relationships among ideas and sentence parts. - Unnecessary commas that make sentences difficult to read are absent. -Two independent clauses are linked with a comma when used with a coordinating conjunction: - ("and," "or," "but," "for," "nor," "so," "yet"). Otherwise, a period or semi-colon is used. - Apostrophes indicate possession for nouns ("Jeanne's hat," "several years' work") but not for personal pronouns ("its," "your," "their," and "whose"). Apostrophes also indicate omissions in contractions ("it's" = "it is"). In general they are not used to indicate plurals. - • Spelling • Capitalization 8 5. Ability to Perceive and Respond to the Implicit and Explicit Communications of Others Responding effectively depends on the ability to read and decipher not just words, but implicit communications -- unstated messages and emotional undertones. Once these communications are decoded, you can decide whether to answer, dismiss objections summarily or not address them at all. We write for three main reasons and audiences: 1. To gain information (staff) 2. To take a position or persuade (Administrators) 3. And finally to inform (Patients) In crafting a response, you must consider your audience. See Competency 1. And be aware of your objectives. See Competency 6. Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: Emotional or interpersonal factors that affect the communication are attended to. • Implicit and explicit communications are responded to in a way that furthers objectives. • Implicit and explicit communications are responded to in a way that does not jeopardize objectives. 9 6. Ability to Write so as to Advance Immediate and Longterm Objectives Deficiencies in skills 1-5 jeopardize the immediate and long-term objectives you wish to achieve through your writing. You also must be able to vary and control your writing according to the evolving context, atmosphere or interaction. Suppose, for example, that your plans are not working as expected: a client complains to your supervisor about your letter, an agency continues to balk at your requests, an opposing position contains derogatory remarks. Or suppose that your plans are working much better than expected. In all these situations, you must be able to adjust your writing and any number of its elements to the situation to achieve your goals. Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: • All elements of writing advance immediate and long-term objectives, e.g., vocabulary, grammar, tone, format, style. • Strategic decisions about what to include or not include advance your objectives. • All implicit and explicit objectives are embodied in the writing. • No messages are conveyed that work at cross-purposes with objectives • Unintended messages are not conveyed; e.g., words and phrases that imply that you're open to settling a case when you're not. 10 Persuasive Writing Competency Materials adopted from Benchmark Institute “Writing workshop for mentors” 11 Persuasive Writing Competency General Definition: Writing to persuade, convince, or compel change of ideas, positions, or outcomes. Ability to write: 1. Preliminary statements that summarize the complaint or issue so that decision makers understand the significance of the law and facts presented. 2. Factual statements that demonstrate the inherent fairness and validity of the writer's position. 3. Point headings that focus decision maker attention on a specific problem in the complaint or issue. 4. Arguments that demonstrate the advocacy bases that compel a conclusion in the client's favor. 5. Challenges to opponents' arguments that assure the decision maker that no critical points have been overlooked. 12 1. Preliminary statements that summarize the complaint or issue so that decision makers understand the significance of the law and facts presented. Like an executive summary, the preliminary statement summarizes the argument's essence--the issues, answers and reasons-- within a factual context. It orients readers to your most important ideas and directs them to the one idea that brings all other ideas and details into focus. It shows your conclusion and helps readers make sense of what follows, e.g., who, what, where, why, and how. Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: • Sufficient information is present to help the decision-maker decide the case quickly and fairly including: -The big picture -- what's the fight all about? who wants what? what's the context within which the situation arose? -Specific questions -- what issues must be decided in order to resolve the matter? -The core of the argument -- why should you win? why do you have a leg to stand on? • Interests of brevity and detail are balanced. • Extraneous information is omitted such as unnecessary boilerplate, irrelevant details, clutter of dates and defined terms. • Information is accurately stated. • Strong, pull-no-punches arguments are made while avoiding hyperbole (exaggerations, over or understatements) raining from attacking the other side personally. 13 2. Factual statements that demonstrate the inherent fairness and validity of the writer's position. Statements of fact contain two types of facts – -facts that create a context for what happened and -facts drawn from the law on which you intend to rely. In crafting the factual statement, you should strive toward making your analysis seem like the only possible means of reaching a just result on the basis of the facts. A compelling statement of facts tells a story. Writing a persuasive story involves thinking about how to frame the facts. Chronology, by itself, does not make a story. Facts may be organized into several patterns: • when -- chronology; • who -- people or institutions such as the parties, government agencies, witnesses, experts; • what -- things such as medications, assistive technology; • where -- location, other geographical context of an incident such as a board and care home; • why -- explanation or motive for events such as discrimination, greed, bureaucratic inertia. Factual statements present a golden opportunity to present the equities of your case. Although you can't characterize facts or draw inferences from the facts in the factual statement, you can allow inferences about the equities to emerge inevitably in readers' minds as their own response. (Writing competency #6-Implicit and explicit communications) Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: • Statement advances the case theory. • Statement contains sufficient context facts and all legally significant facts. Immaterial facts are omitted. 14 3. Point headings that focus decision maker attention on a specific problem in the complaint or issue. Arguments are divided into points; each point an independent ground for relief. For example, arguing that a staff action could be considered a violation because the it was not complaint with the Administrative Directive and it was not supported by regulations, gives rise to two points. Each point becomes a heading; each heading further divided into subheadings. Each sub-heading constitutes a significant step of logic in arguing for the ground of relief or change stated in the heading. Read together, the point headings and sub-headings outline your argument. Point headings and sub-headings contain key facts and applicable legal rules, briefly encapsulating the first paragraph of the argument that follows. Point headings also include the ultimate result that you are requesting, e.g., benefits be granted, action be dismissed. You should word points headings and sub-headings clearly and powerfully- asserting the essential idea and showing how that idea fits into your position. Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: • Point headings focus on an independent ground of request for change in the complaint or issue raised. • The argument's strongest points are included as headings. Insignificant points are not included as headings. • Headings and sub-headings are sequenced persuasively to lead readers to the writer's conclusions. • For each heading, the number of sub-headings equals the significant steps of logic in the argument. • Too many sub-headings fragment the argument so that readers can't quickly see how the argument fits together. 15 • Too few sub-headings hide the argument's logic. • Each heading makes explicit the relief that the writer is seeking. • Headings and sub-headings contain facts and legal rules that show how the law applies to the case. • Headings and sub-headings are presented with forceful assertion. • Headings and sub-headings are stated with precision, clarity and economy according to General Writing Competency #3. • Headings and sub-headings conform to the mechanics of the language according to General Writing Competency #4. 4. Arguments that demonstrate the advocacy bases that compel a conclusion in the client's favor. Your legal argument follows point headings and subheadings. Headings contain a synopsis of the first paragraph of the argument that follows. Begin your argument by giving your conclusion (C); then a brief statement of the rule to support the conclusion, telling why you should win (R); then a detailed analysis of the facts (A); and finally your cases (C). Discussion of cases should come at the end, unless a case is so central or new that you must discuss it first. Key or controlling cases must be discussed in detail, but the intricacies of other cases can be explained in a phrase, clause or parenthetical. Quote someone if the quotation speaks directly to the point or if the author said something far more eloquently than you could. Quoting the court's own words back to it is most always a good idea. 16 Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: • Argument is structured for clarity and persuasive impact. - The argument supports assertion in point heading. - Structure follows the CRAC method. are explained using court opinions, legislative purpose or history, statutory language, interpretive canons, policy considerations. - Attack is focused on a few strong points vs. blunderbuss approach. - Controlling court opinions are analyzed and relied on to support major propositions by stating key facts, holding and rationale. - Strongest legal argument is emphasized (precedent v. equity and policy). • Fact Analysis - How legal rules operate on the facts is demonstrated. - Any quotations are brief and appropriate. - Facts are connected to each essential element of enacted law. • Legal Rules are defined and explained. - Key facts of court opinions are compared to key facts of case to demonstrate similarity or dissimilarity. - Best and most applicable authority is selected. - Superfluous and irrelevant authority is excluded. - Extending, limiting or rejecting a legal rule is explained by referring to appropriate authority and the key facts of the case. - Elements of enacted law at issue 17 5. Challenges to opponents' arguments that assure the decision maker that no critical points have been overlooked. Your job is to address the other side's principal allegations and in ways that support arguments that you have already made. You don't have to respond to your opponent's every argument. Be careful not to over argue your case. It's usually not helpful to take your opponent's arguments and talk about all the dire things that will happen if the decision maker rules against you. Focusing on personalities suggests that you're weak on the merits. Rarely if ever mention the other side. If you must challenge them, do it in a straightforward way; e.g., "the cases cited by defendant do not apply." Behaving like a junkyard dog toward your opponent confuses strength with shrillness and sarcasm. Indicators you have accomplished your goal in writing competency: • Opponent's principal points are strategically addressed. • Opponent's principal points are not ignored. • Opponent's key arguments are effectively distinguished or explained away. • Hyperbole and personality attacks are avoided. 18 Writing Steps Materials adopted from Benchmark Institute “Writing workshop for mentors” 19 Writing Steps Develop your Thoughts What is your general direction, purpose, goal? Will you need assistance from others such more information from the client or your supervisor? Research Find rules, regulations, codes, or past practices. Organize Begin to note relevant information. Rethink your theory Are your first thoughts on this still correct? Is the information you are gaining changing your thoughts on this complaint / issue? What if any additional information do you need at this point? Organize Now you have your information and you have a direction. Begin to organize your thoughts more formally. Compose Write what you know, are there gaps? What do you understand about the facts or don’t know? Write from your impressions, do you need more details? Are you missing information? Write around it and do more research to fill in your missing information. Assess Communication Situation Has your purpose, audience, or tone changed? Include necessary context; clarify your terms and concepts. Assess your Organization Does your structure work? Is it in logical order? If needed, move your paragraphs and sentences into an order your reader will understand. Check to make certain you are reaching your conclusion. Rewrite You have solved the problems in your writing to your satisfaction, now make certain you have satisfied the reader Edit for Length, Clarity, Continuity Cut out lengthy substantive discussion. Eliminate clutter, redundancies, an windy phrases. Get over yourself. Your reader will not be impressed if you do not write to suit their needs which is often getting to the point and respecting their time restrictions. Remove lawyer-isms, double negatives, redundant words, flowery phrases. Edit for consistency. First person to third person. References to people, policies, and laws. Proofread Have some else do a read through to check for spelling, typos, punctuation, and citations. We often do not see our own mistakes. 20 Final Review of Your Writing Product Did you write appropriately to your reader/audience? In our daily writing, we write for three main reasons: 4. To gain information (staff) 5. To take a position or persuade (Administrators) 6. And finally to inform (Patients) What is the quality of the content: ideas, arguments, analysis, and advice? Did you express each thought with precision, clarity, and economy? Are your thoughts presented in an organized manner? Did you perceive and respond to the implicit and explicit communications of others? Does it advance immediate and long term objectives? Was your use of language mechanics correct? 21 Why Plain English Materials adopted from “Plain English for Lawyers” by Richard C. Wydick 22 Why Plain English In school, some lines of work, and as exampled by most lawyers, we use eight words to say what could be said in two. Often, trying to be precise, we become redundant. Seeking to be cautious, we become verbose. Our sentences go on and on often causing our reader get lost or to skip to the last paragraph to find out what we want. To avoid appearing wordy, unclear, pompous, or dull, lets begin to untwist some or our own writings. To do this we must first; Omit Surplus Words Lets take a look at some of our writings and see what we have…In every sentence there are two kinds of words: working words and glue words. Working WordsThese carry the meaning of the sentence. Glue WordsThey hold the working words together. They form a proper, grammatical sentence. Think of anything you build: too much glue and you have a mess, not enough glue and you have pieces. Our goal is to use just enough glue to keep the pieces together. 23 Avoid Compound Constructions Compound constructions use three or more words to do the work of one or two words. They suck the vital juices form your writing. Here are some examples: At that point in time for the reason that In order to In relation to Subsequent to With reference to In favor of then because to about after concerning for Avoid Word-Wasting Idioms (Figures of speech) Once you recognize surplus words, you will find many word-wasting idiom to trim from your writings. The fact that she died He was aware of the fact that In many cases you will find Despite the fact that In some instances Her death He knew that Often you will find Although, even though sometimes 24 Focus on the Actor, the Action, and the Object One way to know if you have a wordy and bog-downed sentence is to ask yourself: “Who is doing what to whom in this sentence?” Write your sentence with the focus of three key elements – the actor, the action, and the object of the action (if there is an object). First, state the actor. Then, state the action, using the strongest verb that will fit. Last, state the object of the action, if there is an object. Use Short Sentences In most of your writings, you sentences should have one main thought and contain 25 words or less. Use Familiar Words So you want to impress…use words that are current and ordinary. A reader’s time is precious. Don’t waste it by creating distractions. The convenience of the reader must take precedence over the writer’s self-gratification. When Necessary, Make a List Sometimes the best way to present a cluster of issues, conditions, or exceptions is to list them. Begin with an introduction clause that leads to the list. Use a colon at the end of the clause and at the end of each item in the list use either a coma or a semicolon. 25