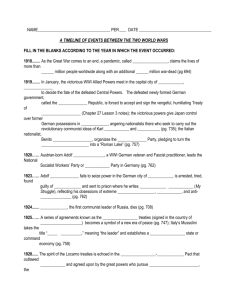

Foreign policy in the 1930s - long essay

advertisement

Evaluate the view that Soviet foreign policy was dominated by practical rather than ideological concerns in the period 1928-1941. Soviet foreign policy was motivated by both practical and ideological considerations in the period between 1928 and 1941. During the years of Stalin’s campaign against the kulaks, foreign policy was pursued with the same ideological zeal. However, when pragmatism came to the fore domestically, it did so too at an international level. The foreign policy pursued by the USSR in the period up until 1929 was essentially pragmatic – attempting to foster cooperation with the capitalist nations, in order to defend the Revolution from attack. To mollify international opinion, the Bolsheviks ordered all communist parties around the world to end their hostility to the socialist parties in their respective countries. The hope was that if the political left united, this might allow the socialists to come to power, thereby increasing the likelihood of cooperation with the USSR. For this reason, the policy was known as the ‘united front’. Unfortunately, the policy failed to end Russia’s diplomatic isolation, and in 1929 Stalin set the nation in a new direction – one dictated by uncompromising MarxistLeninist ideology. He decided to bring all international communist parties into line with the radical policies he was embracing in Russia (collectivisation and central planning). These parties were now ordered to end all cooperation with other leftist groups, whom they branded ‘social fascists’ – Stalin’s logic being that the Great Depression would soon bring about a wave of revolutions and that the Communists must eliminate rival leftist groups in preparation for taking power. The result of this policy shift was disastrous. The German Communist Party directed its opposition to the Social Democrats rather than the Nazis, allowing the Nazis to become the largest party in Germany. Within four years, Hitler had become leader and the Communist Party banned. Other left wing groups soon followed. All military cooperation between Germany and Russia ended. Stalin now realised his mistake, and switched his foreign policy back to a more pragmatic approach. He immediately began seeking better relations with the western nations, in the hope of ending Russia’s diplomatic isolation. In consequence, the United States recognised Russia for the first time since the Revolution (1933), and the USSR joined the League of Nations (1934). Stalin also signed treaties of alliance with France and Czechoslovakia in 1935, and ordered the various international communist parties to form a ‘Popular Front’ with all anti-fascist groups in Europe. Unfortunately, Stalin’s attempts to woo Britain and France into an alliance against Germany failed. Both nations stood by while Germany reoccupied the Rhineland, then invaded Austria in 1938. When Hitler began making demands on Czechoslovakia, Stalin tried to get France to make a stand – enforcing the 1935 treaty to defend the country. However, France was not willing to contemplate a war with Germany at that stage. At the Munich Conference in 1938, France and Britain gave Hitler control of the border regions of Czechoslovakia. As historian J.N. Westwood has put it: “Thus the Munich agreement of 1938 was not only a betrayal of Czechoslovakia, but in a sense of Russia too. Probably it was at this time that Stalin began to visualise his own Munich, a bargain with Germany. He still preferred an alliance with Britain and France but these two powers, though less uncongenial, seemed unenthusiastic and unreliable. He probably did not expect the western powers to fulfill Britain's guarantee of the Polish frontiers in the event of a German attack.” (Westwood: 331) The first hint of Stalin's intentions came in April 1939, when he replaced the prowestern Litvinov with Molotov as foreign minister. The Germans responded by offering Russia large tracts of land in Eastern Europe in return for Russian neutrality in their coming war with Poland. For Stalin, this was an attractive proposition, since it gave him breathing space to build up his forces and recover from the purge of the Red Army. It also gave him a buffer zone against future German aggression. When Britain and France were unable to make an acceptable counter offer, Stalin decided they were not serious about an alliance. In August 1939, he accepted the German offer and signed a ten-year Non-Aggression Pact (the so-called ‘Nazi-Soviet Pact’). On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two and a half weeks later – once the Polish army had been defeated – the Red Army did likewise. Germany and Russia formally agreed to partition Poland and eliminate it as a state. Even before the ink had dried on the pact, and before the blood had dried in the streets of Warsaw, Stalin began preparing for the attack he knew would come. This time, though, he was without allies. The best he could hope for was to lull Hitler into believing Russia was no threat to him, thereby delaying for as long as possible the inevitable attack on the USSR. And so by 1941, Russian foreign policy had come full circle twice over – from the mild pragmatism of the ‘United Front’, to the ideology-driven war against the ‘social fascists’, to the desperate pragmatism of the ‘Popular Front’, to the cynicism of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. It was this inconsistency in policy, more than anything, which isolated the USSR during the period, and which left it vulnerable to an attack by its greatest enemy, Nazi Germany.