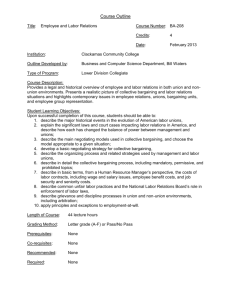

Contract Interpretation

Contract Interpretation Grievances

The moving party is the union. The union has the burden of proof. The union must demonstrate that management has violated the collective bargaining agreement.

The agreement, however, may go beyond a simple reading of the contract.

Arbitrators begin by asking:

•Is there any contract language that directly applies to the fact pattern in this case?

•Is the language specific?

Specific language is controlling over general language.

Is the language clear or ambiguous?

Standard definitions of words defeat technical definitions unless the words are defined in the contract. Terms and phrases must be given consistent meaning throughout the contract (four corners test).

Clear and unambiguous language generally prevails over past practice.

What did the parties intend when they bargained the contract? Are there any minutes or notes from the negotiations?

Where the contract language is ambiguous or the contract is silent, past practice can be used to give the contract meaning. Several questions need to asked about past practices :

•Is there mutuality in the practice?

•What is the history of the practice?

•Is the practice clear and consistent?

•How many times has it been repeated?

•Has it been a widely accepted practice?

•What conditions gave rise to the practice and have those conditions changed?

Is there specific language in the contract covering the issue?

"Specific" means constituting or falling into a named category. A contract provision can constitute or fall into a named category and yet be loosely written, vague, and ambiguous in its treatment of that category. For example:

Supervisors may perform work in the bargaining unit in emergencies only, or for the purpose of instruction.

The named category is "supervisors performing bargaining unit work."

Yet, what does the language mean? Regardless, such specific language will take precedence over general language.

Contract Interpretation

General language deals with the issue, not as the named category but by inference only.

For example:

Section 1: Short vacancies of less than 30 days duration may be filled without posting at the option of the Department Head.

At issue was an employee's birthday, a category listed in another provision of the contract as one of the eight paid holidays. The aggrieved employee had asked to work his birthday holiday, which would have entitled him to 2 1/2 times his straight-time hourly rate. Does Section 1 cover the issue?

Negotiating Specific Language Can Backfire

Specific language is so controlling in contract interpretation that when the contract is entirely silent on a particular matter, the union may be better advised to let well enough alone rather than negotiate language which does not clearly spell out its expectations.

For example, the following language was proposed by a union and accepted by management:

It is agreed that all work shall be performed as much as practicable by union labor in the employer's own shop. In the event that all work cannot be rendered in the shop of the employer, the employer may contract his work to union shops only; provided that if union shops will not accept such work or are unobtainable for such work, then the employer may contract such work elsewhere.

It would appear that the union made an impressive gain on subcontracting, but the union's position would have been stronger if it had allowed the contract to remain silent on the issue. Why? Many arbitrators rely on the union recognition provision in the collective bargaining agreement to not sustain management if the subcontracting results in layoffs or the impairment of established employee benefits (provided that subcontracting is not a customary method of business or there has not been a drastic change in the underlying conditions of the jobs in question). But, when specific language on subcontracting is written into the agreement, it is not with the province of the arbitrator to go outside that language, except to fill gaps, to determine the intent of the parties. The specific language now supersedes standard arbitration criteria, which would have prevailed if the contract remained silent.

Clear and Unambiguous Language Is Generally Controlling Over Past

Practice

Is the language clear and unambiguous with respect to the issue?

If the words are clear and free of doubt as to their meaning, the arbitrator must stop right there. The language speaks for itself. If an arbitrator infers a different meaning when the language is clear by resorting to some other criteria, such as past practice, this

Collective Bargaining Page 2 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation would ordinarily constitute an abuse of his authority. A court could then set aside the award. For example:

Lunch Period: "All employees in the bargaining unit shall have a thirty minute lunch period, except for ....(not including stationary engineers).”

For some thirty years, the company's stationary engineers had occupied themselves in the boiler room with no designated lunch period during their entire shift. Although their responsibilities were great, their tasks were not burdensome.

They primarily read gauges, took notes in a log, occasionally turned gauges, or wiped up oil remnants with a rag. They usually ate lunch while they worked.

Since the union in thirty years had never made an issue of a designated lunch period for the engineers, the company regarded the matter as settled and did not try to amend the language to bring it into conformity with its practice. Then an entirely new slate of union officers took over following a bitter election campaign.

They claimed the old officers had failed to represent the members and enforce the contract. The new officers immediately filed a grievance on behalf of the engineers and pushed it into arbitration. The company pointed to a thirty year unchallenged past practice. The arbitrator sustained the union, holding that the omission of the stationary engineers from the exempt classifications inescapably and unambiguously placed them in the category of employees entitled to a thirty minute paid lunch.

Unambiguity Is Never Absolute

First, like beauty, unambiguity is often in the eye of the beholder. Second, language which is unambiguous in respect to a given issue can be hopelessly vague and uncertain in regard to another issue. Language is clear if it is something less than ambiguous. Third, if the language points in one direction and the practice points in another, go with the language.

The Question Reformulated:

Is the contract sufficiently clear in respect to the issue that the mutual intent of the parties can be discerned with no other guide than a simple reading of the pertinent language? If the answer is no, then the language must be ambiguous.

Ambiguity: Patent and Latent

Although ambiguous and unambiguous language are opposites, they have a reciprocal relationship to each other -- that is, they are defined one through the other.

Language is said to be unambiguous when a simple reading clearly and plainly suggests a single meaning and is susceptible to only one interpretation. Counter-examples of unambiguity are:

The mother was a small farmer's daughter.

Collective Bargaining Page 3 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation

Who or what was small?

An employee who does not work the day before the holiday or the day after the holiday will not be paid for the holiday.

Does the employee need only work one day, either before or after the holiday? Or, does the employee need to work both the day before and the day after the holiday?

Patent Ambiguity :

A patent ambiguity is one which appears on the very face of the language; it is an ambiguity which arises because the language used is defective, obscure, or insensible.

Not all ambiguities arise from defects in language.

Latent Ambiguity :

Language is said to possess a latent ambiguity when it is clear and intelligible and suggests a single meaning, but some extrinsic fact or evidence makes the language susceptible to more than one interpretation. For example:

The Four Corners of the Agreement

The primary rule in interpreting a written agreement is not to rely on a single word or phrase, but to learn the meaning of a questioned word by understanding how it is used in all other parts and provisions of the agreement.

Alternative interpretations of a clause are possible; one could give meaning and effect to one provision of the contract, while another could render the other provision meaningless or ineffective. The arbitrator will be inclined to use the interpretation which would give effect to all provisions.

When one interpretation of an ambiguous provision would lead to harsh, absurd, or nonsensical results, while an alternative interpretation, equally consistent, would lead to just and reasonable results, the latter interpretation is used.

Arbitrators sometimes apply the principle that to expressly include one or more of a class or category in a written statement is to exclude all others. For example, an employee with 20 years service with the company, but only one year in the bargaining unit, was specifically entitled to vacation benefits based on company service by a specific provision in the written agreement. The arbitrator concluded that, since sick leave was not specifically mentioned in that provision, it must have been the intent of the parties to

Collective Bargaining Page 4 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation base sick leave credit on bargaining unit accrued service; otherwise the parties would have included it in the list of benefits based on company service.

Where general words follow an enumeration of specific terms, the general words will be interpreted to include or cover only things in the class or category listed specifically. For example, a clause providing that seniority shall govern all cases of

"layoff, transfer, or other adjustment of personnel" should not be considered to require allocation of overtime on a seniority basis.

Sources of Contract Ambiguity:

Deceptively Simple or Simply Deceptive?

By far, the principal source of contract ambiguities is the inherent limitations of language itself, both oral and written. Negotiators cannot write language to cover every possible situation. Language has meaning only in respect to an issue in dispute. The most frequent problems which arise during the life of a contract are those which were not anticipated by the parties when the language was created.

Ambiguous language is often used to disguise disagreement. During negotiations, parties intentionally leave language ambiguous rather than hold up an otherwise acceptable settlement. These are purposeful ambiguities. This is language that neither side is willing to totally concede or go all out to win. The failure of the parties to reform the language when the contract is open amounts to a tacit agreement that the ambiguities may be either negotiated during the life of the agreement or settled in binding arbitration.

Often these ambiguities cannot be prematurely removed without upsetting a delicate balance in the relationship between the parties of which the ambiguity is but a surface manifestation.

A Case on Promotions & Seniority

Section XXI--Crew Leader

D. In the selection of a crew leader the more senior employee in the Section where the opening occurs, and then in the Department, shall be given first consideration for the appointment to crew leader provided that he or she possesses the qualifications, ability and physical fitness to perform the job and the candidate's past conduct and attendance are satisfactory.

The grievant was the senior employee in the section with fourteen years seniority.

He was passed over for another employee with ten years seniority. At the heart of the controversy was the phrase "first consideration."

Collective Bargaining Page 5 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation

The union argued that if the senior employee met the requirements of the provision, as the grievant did, then the employer should proceed no further, but was obligated to promote him to crew leader.

The company insisted that Section XXI(D) did not preclude management from considering other prospective appointees in the order of their seniority, subjecting them to the same tests as those put to the most senior employee. Then management would select the employee with the highest seniority who was deemed most capable.

The company offered proof of its interpretation by introducing a six-year record of adhering to the appointment procedure in dispute. Of 16 appointments made in that period, on only three instances was the most senior employee selected to fill the crew leader vacancy; a junior employee was selected thirteen times. Only twice did the union challenge the appointments.

The contract provided that the more senior employee be given first consideration.

The senior employee must possess the qualifications, ability, and physical fitness to perform the job, and the employee's conduct and attendance must be satisfactory. The company insists that the job must be awarded to the most capable employee as measured by these criteria. The unions argued the grievant meets all the basic criteria in XXI(D).

The company does not dispute this.

The arbitrator turned to the standard reference text, Elkouri and Elkouri, How

Arbitration Works (DC:BNA), to gather some background on seniority disputes. He found that it is a popular misconception that unionized establishments rely exclusively on seniority for promotion. Data indicate that only 4% have a strict seniority rule, and they usually have short job ladders. Most collective bargaining agreements contain one of three forms of modified seniority clauses.

1) Relative ability -- seniority shall govern if ability and other qualifying factors are relatively equal, substantially equal, or simply equal.

2) Sufficient ability -- the senior employee will be promoted if he or she possesses sufficient ability and meets the other qualifications to perform the job. Comparisons with other employees are unnecessary and improper.

3) Hybrid -- requires consideration of both seniority and ability but the weighting may vary from case to case. Thus a high seniority, low ability employee could be passed over for an employee with greater ability and less seniority.

What type of seniority clause is XXI(D)? What is your ruling?

Now, use the promotion language in your contract. What type of seniority clause is it? Using the same facts presented in this case, but your contract language, what is your ruling?

Collective Bargaining Page 6 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation

Tests

Although not an issue in this dispute, for your information, arbitrators generally hold that tests used in determining ability must meet four criteria:

1) Tests must be related to the skill and knowledge required in the job.

2) A test will be considered fair and reasonable if it covers relevant factors, is not unduly difficult, and is given under proper conditions.

3) The test must be fairly administered, graded, and uniformly applied. It must be given to all applicants without undue advantage.

4) The test must be properly evaluated in the light of the contract provisions relating to seniority and job requirements, and it must not be used in a manner inconsistent with the contract.

Even in the absence of specific contract provisions, management has been held to give reasonable and appropriate written and oral performance exams and aptitude tests as an aid in determining the ability of competing employees.

Management Rights & Employee Rights: The De Minimis Rule

The operation of an organization can be divided between two main areas of responsibility. One area consists of those functions which are exclusively management rights. Management certainly would like this to be as expansive as possible. Although labor wants to limit these issues, many labor leaders historically have accepted issues such as the determination of the product, the machines, the method of operation, the price, the organizational structure, the marketing strategy, and innumerable other questions as exclusively management rights. On the other hand, Neil Chamberlain attempted to isolate a pure management function and concluded that the task of coordination is the only unique function of management.

The other main area of responsibility covers the terms and conditions of employment, including the direction of the workforce. Authority in the area is not an exclusive function of management, but may be subject to collective bargaining. The sharing of this authority is in some respects regulated by law, but even more fundamentally, the degree and extent of the sharing is determined by a balancing of strengths of the parties.

No hard and fast line of demarcation exists between these two areas of responsibility. How should we decide whether something is a management function?

The Major-Minor Test or the De Minimis Rule

When the employee benefit is minor and the contract language is ambiguous or silent, the practice is considered a basic management function which can be altered or abolished at management's discretion. When the benefits are major, doubts are generally

Collective Bargaining Page 7 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation resolved in favor of the employees, and the practice is considered a basic employee benefit which cannot be withdrawn until the contract is open. This deliberate weighing of the scales as to what is major or minor to reach a decision is inescapable in any judicial process.

Case of a Supervisor Performing Bargaining Unit Work

Consider the following case, in which the issue was whether the work of a supervisor in operating a fork lift on a holiday constituted a violation of the contract for which the grievant is entitle to pay. The contract clauses involved are:

Article IX -- Management

9.2 It is the policy of the Company that supervisors and other salaried employees of the company at the plant shall not spend their time performing manual labor which is normally performed exclusively by members of the bargaining unit, except in cases of imminent safety hazards to persons or property, momentary assistance, instruction or experimentation.

Article II -- Hours and Wages

2.6 Employees scheduled to work on Saturdays, Sundays, or Holidays shall be guaranteed a minimum of four (4) hours of work within their department.

Employees called in for special call shall not be required to continue working after completing the work for which they were called in, in order to receive minimum pay.

On President's Day, a plant holiday, an outside contractor came to the plant with a crew of men to clean out a pit. It was customary for the contractor to advise the company before arriving to perform this routine clean-up. The plant guard admitted the contractor, who went to the work area, where he found that the opening to the pit was obstructed by several pallets. Frank Smith, a supervisor, was finishing up some paperwork in his office when the plant guard called and told him about the obstruction. Using a fork lift, Mr.

Smith moved the pallets a few feet.

The union argued that this action constituted a violation of Section 9.2 of the contract and requested four hours pay for the fork lift operator.

The company argued that the violation was so minor in nature that it should be disregarded. It took Mr. Smith less than five minutes to move the pallets. There were no bargaining unit employees in the plant. It would have taken considerable time for an employee to arrive and move the pallets. The company could not have planned for this contingency, because the contractor had not provided notice. The offense is so minor in nature, that the de minimus rule should be applied.

What is your decision?

Collective Bargaining Page 8 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation

What Is the Intent of the Parties?

The primary rule for interpreting agreements is to give effect to the mutual intent of the parties. In determining the intent of the parties, inquiry is made as to what the language meant to the parties when the agreement was written. It is that meaning that governs when the contract is ambiguous.

Precontract Negotiations

The records from contract negotiations are often used as an aid to interpret ambiguous language. The arbitrator will examine the evidence to discover what the parties intended or did not intend during negotiations of a particular issue. The arbitrator may request a detailed bargaining record and history be supplied. Recordings, notes and minutes can be important evidence. The intent demonstrated by the parties during negotiations is considered most important.

There is a hazard in making specific contract demands in negotiations. If the language does not appear in the agreement, the party who proposed the language has the burden of proof in an arbitration procedure that its omission should not be interpreted as a rejection of a proposal that prevailed. Arbitrators are averse to granting benefits through interpretation that were rejected in negotiations. It is fundamental that the arbitrator not grant to a party that which it could not obtain in bargaining.

Where a proposal in bargaining is made to clarify ambiguous language in the agreement, its omission from the final agreement does not necessarily mean that the interpretation of the ambiguous language offered by the unsuccessful party is wrong.

When making a proposal a party should use language that does not leave the matter in doubt. Where doubt remains, ambiguity persists, and if no other rule of interpretation is available, the arbitrator will find against the party who proposed the ambiguous language.

Prior Grievance Settlements

Where the parties themselves settle a grievance involving ambiguous language, that settlement carries special weight, which helps reveal their intent. In effect, mutual settlements often constitute binding precedents for the parties. Similarly, even oral agreements of the parties as to the application of ambiguous language may be given significant weight by an arbitrator in interpreting that language if such oral agreements can be proven.

Past Practice Where There Is Ambiguous Contract Language

In general, the standard of past practice is used more extensively than any other for giving meaning to ambiguous contract language. Meaning can be established by the conduct of the parties, whether that conduct is by words or by action without words. It is

Collective Bargaining Page 9 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation a well settled principle of arbitration that where past practice has established a meaning for language subsequently used in new agreements, the new language will have the meaning given it by the past practice.

The Case of the Scheduled Work Day and Holiday Pay

The dispute involved the meaning of the phrase "scheduled work day." The contract states:

Section X(e) : Employees working the scheduled work day before and the scheduled work day after a holiday, shall receive pay for the holiday.

The company is a meat-packing house and the eight grievants are represented by the UFCW. The eight employees claimed pay for the 1983 Christmas holiday. They had been laid off on December 20 and recalled to work on December 30. During this period the entire plant was working, except the killing department, where the eight workers were employed. The employees worked the scheduled work day following their layoff, but not the scheduled work day after the plant holiday, which was December 26 for the rest of the plant's employees.

Exactly the same situation occurred in 1979, 1980, and 1982. The laid-off employees were not paid for the holiday, but the union made no formal protest on those prior occasions. Section X had remained unchanged for more than the five years prior to

Christmas 1983.

The union argued that "the scheduled work day after the holiday" referred to the first day the grievants returned to employment from layoff. The company disagreed, contending that "the scheduled work day after a holiday" referred, not to the day on which the grievants returned to work from layoff, but to the scheduled work day for the entire plant, a day on which the grievants were still on layoff.

What is your decision? What does scheduled work day mean?

Past Practice Cannot Be Nullified by General (Zipper) Provisions

Past practice as a standard for interpreting ambiguous contract language cannot be nullified by general provisions which declare that the written instrument terminates all past understandings and is the complete agreement of the parties. Such management rights provisions are often referred to as zipper clauses -- since they zipper up the agreement.

Company Manuals and Handbooks

Company-issued booklets, manuals, and handbooks which have not been negotiated or agreed to by the unions are said to constitute merely a unilateral statement

Collective Bargaining Page 10 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation by the company and are not sufficient to bind the union. Arbitrators give these publications little or no weight in the interpretation of disputed contract language.

Past Practice When the Contract Is Silent

Those management practices which are not covered by any language in the contract but confer benefits on employees go to the heart of the management reservedrights doctrine. In most instances they originate as reserved rights, as exercises of managerial initiative that may become binding.

What rights should management be held to have given up in the agreement?

It is necessary to differentiate between those employee benefits initiated unilaterally by management which become binding conditions of employment and other benefits that, regardless of how much employees come to rely upon them, can be withdrawn at management's discretion. Benefits that can be withdrawn at management's discretion can be divided into two types: (1) gratuities and (2) unintended benefits, which are incidental by-products of the organization of production and services.

Gratuities

Bonuses, especially Christmas bonuses, are a common source of controversy. In a typical case, the union contends that, although there is nothing in the contract providing for the distribution of Christmas bonuses, the employer has a long history of providing bonuses at Christmas, and employees have come to depend on them. The Company responds that each year it has announced a Christmas bonus, based on a decision of the board of directors at that time. Arbitrators will find for the company, if each year the

Company takes special action and gives special notice to the employees.

Recurrence of a gratuity does not constitute a binding practice. Where the payment made each year is dependent on the discretion of management, there can be no contractual obligation to continue the payment during the life of any contract.

To be considered a binding practice, a practice cannot require a separate decision each time. A binding practice must obligate the company to follow a certain course of conduct. In the case of a gratuity, the company must commit to the payment of year-end compensation.

Converting Gratuities into Binding Practices

A gratuity is a gift. It must be a voluntary offering involving no mandatory exchange. In negotiations, however, it is often difficult for an employer to resist using a bonus as an indirect bargaining chip. The employer will use the gratuity as proof of his generally beneficent attitude toward the employees. The more the employer relies on the bonus as means to gain acceptance of an economic package, the more likely the

Collective Bargaining Page 11 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation employees will view the bonus as part of the settlement. As a result, the gratuity is converted into a binding practice.

As another example, a long standing practice of providing free coffee during rest period and at lunchtime originated as a gratuity but was converted by the company into a binding practice during negotiations. The arbitrator found:

The company cited the provision of free coffee as a fringe benefit in negotiations to counter a demand by the union for medical insurance for dependents. The evidence is clear to the arbitrator that the provision of free coffee was cited to the union as a fringe benefit which the workers enjoyed.

Unintended and Incidental Benefits

Another non-binding practice can arise as an incidental by-product or unintended result of the operations of the enterprise. For example:

At a suburban location employees have the use of a parking lot adjacent to their office building. As a result of a reorganization, their work is shifted into the city, where the office buildings do not have adjacent parking lots. There is no language in the contract on parking nor has it been a subject of negotiations.

Does the company need to provide free parking for these employees?

Determining Whether a Practice is Binding: Eight Criteria

One type of gratuity is intentional and the other incidental, neither is binding.

Employee benefits exist that are not spelled out in the contract, are not in the category of gratuities, and which depend for their enforcement on a binding custom or practice.

There are eight criteria for determining whether a practice is binding:

1. Does the practice concern a major condition of employment?

2. Was it established unilaterally?

3. Is it administered unilaterally?

4. Did either party seek to incorporate it into the written agreement?

5. How often is the practice repeated?

6. Is the practice a long-standing one?

7. Is it specific and detailed?

8. Do the employees rely on it?

A Case of Severance Pay

Collective Bargaining Page 12 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation

The claim of severance pay was made by the union on behalf of a group of salesmen who had been given an indefinite layoff because of unfavorable business conditions. The union asserted the existence of a past practice. The "past practice" the union relied upon was based on numerous occasions (in cases of layoff and even discharge) when the company had, after discussion and at behest of the union, given severance pay to affected employees in varying amounts which could be described as fair and reasonable.

The union argued that this consistent action removed the matter of the severance pay from the category of a gratuity, which could be unilaterally granted or withheld by the company, and gave it the status of a benefit, which employees could properly expect and rely upon and which the parties understood and accepted as mutually binding and enforceable.

The company maintained that the contract was barren of any mention or grant of severance pay at the time of layoff, that such an essential element of employment would most certainly have been reflected and included in the contract if actually agreed upon, and that under no circumstances should the company be penalized or entrapped into a binding commitment by its prior gracious and gratuitous acts.

Apply the eight criteria. What is your decision?

Mutuality is the Key to a Binding Practice

Mutuality is the underlying purpose common to all eight criteria for determining a whether a practice is binding. If the employee benefit is minor, then the practice is a basic function of management and mutuality is irrelevant. If the practice was administered unilaterally, the burden is on the party asserting its validity to establish a sufficient element of mutuality to make the practice binding. Mutuality may be proven by the conduct of negotiations. The practice may be so rarely repeated, so short in duration, or so fragmentary that employees cannot be said to have relied on it, and a claim of mutuality cannot be made.

In essence, a past practice constitutes the parties' uniform and constant response to a recurring set of circumstances. The party asserting a past practice bears the burden of proof with a preponderance of clear and definite evidence.

An Unusual Case of Local Working Conditions: Bethlehem Steel

A group of employees at a Bethlehem Steel plant initiated a 20-minute lunch period on company time without the express consent of management. As "straight through" employees, they were scheduled to work a continuous eight-hour day, squeezing in an undetermined lunch break during working hours. Straight through employees began their lunch breaks at the same time as employees entitled to thirty minutes. In time, many straight through employees were taking a full thirty minutes for lunch. Management

Collective Bargaining Page 13 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation remedied the problem by announcing that straight through employees would be limited to a ten-minute break from 11:50 am to 12 noon.

The union claimed that management was cutting in half the lunch period previously taken by straight-through employees, which had become a local working practice. There is no doubt that straight through employees had regularly taken a 20minute lunch. The mere fact that supervision did not direct that a 20-minute lunch be taken does not mean that a local working practice did not emerge. Supervision was aware of the practice, tolerated it and acquiesced to the 20-minute lunch. For a practice to become binding, management does not have to make a specific agreement or sanction it.

The company took the position that supervision never instituted a 20-minute policy. Even if the employees had customarily taken a 20-minute lunch period, supervision never sanctioned it; without such sanction, the claimed practice could not be considered binding since there is no showing of mutuality.

What is your decision?

Binding Past Practices Almost Always Originate with Management - Not

Employees!

Management practices are much more likely to indicate mutuality than employee practices. Employee benefits are generally instituted through management action rather than through the unilateral practices of employees.

Binding Past Practices Are Based on Underlying Conditions

In general, the practice of the parties reveals their expectation for the immediate future. The binding character of a practice is linked directly to the underlying conditions of its origin and subsequent development.

When the underlying conditions of a binding practice not mentioned in the contract remain unchanged, the employer cannot unilaterally withdraw the practice until the contract is open for negotiations. When the underlying conditions do undergo a significant change, the casual relationship between the new conditions and the old established practice is said to be broken. Most arbitrators hold that if the underlying basis for the practice changes, management may alter or discontinue the practice even while the contract is in effect. There is no fixed rule on how long management can wait before changing, eliminating, or modifying the practice after the underlying conditions have changed. Some arbitrators have ruled, however, that an undue, unreasonable delay in making the change suggests that the new conditions have not significantly altered the underlying basis for the established practice and that, therefore, the practice must be continued for the contract term.

A Case on the Assignment of Helpers

Collective Bargaining Page 14 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

Contract Interpretation

For many years, the plant practice had been to assign one helper to each boilermaker. However, certain changes began to take place in underlying working conditions in 1968: welding operations increased, riveting work declined, and the company installed new cranes. The net effect of these changes was to decrease the helpers' work and increase their idle time. Finally, around mid-1974, the company decided to layoff five helpers while adding two boilermakers. A month later, the company laid-off four more helpers, while it continued to increase the number of boilermakers.

The union filed a grievance protesting the company's altering of the past practice of assigning one helper to each boilermaker. It argued that any change in underlying conditions had occurred years ago, and that the company had continued the practice after the underlying conditions had changed. There is no proven relationship between the change in the workload conditions and the elimination of the past practice.

The company eliminated the local working condition in question because of its belief that the workload of the boilermaker's helper had declined to the point where they were no longer required to give a full day's work for a full day's pay. The reasons for the decrease in the helper's work load are the introduction of new cranes and the shift from riveting to welding. These changes have had a cumulative effect on reducing the helpers’ workload.

What is your decision?

A Binding Practice Is a Reserved Right Plus Mutuality

Mutuality, when the contract is silent on a practice, is the essential ingredient which transforms the practice into an implied obligation. Mutuality is the connecting link, the common denominator of management's reserved rights and management's implied obligations.

The material is this section is based on the major source for arbitration:

Frank Elkouri and Edna Elkouri. How Arbitration Works (6th ed.) (DC: BNA). (Labor and Employment Bar)

Collective Bargaining Page 15 R UTGERS U NIVERSITY

![Labor Management Relations [Opens in New Window]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006750373_1-d299a6861c58d67d0e98709a44e4f857-300x300.png)