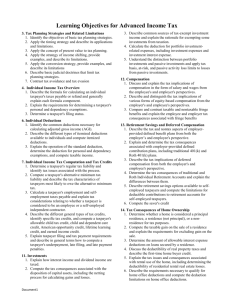

Federal Income Taxation – Course Outline

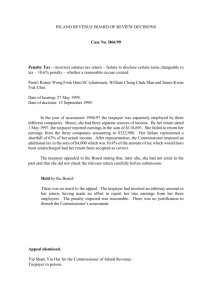

advertisement