DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

National Center on the Sexual Behavior of Youth

Title of Chapter:

Guidelines for Placement Within a Continuum of Care for Adolescent Sex

Offenders and Children with Sexual Behavior Problems

Duration:

1-2 hours

Target Audience:

Attorneys, Judges, Law Enforcement, Probation, Child Welfare Workers,

Mental Health Practitioners

Prepared by:

Mark Chaffin, Ph.D. & Robert Longo, MRC LPC

(NOTE: The following concepts are to be presented by the leader or co-leaders of the training

session. It is recommended that the presenter be a licensed mental health practitioner with

knowledge of the literature and experience in treating adolescent sex offenders)

Purpose: The purpose of this workshop is to provide guidance for decision-making in the type,

intensity, and location of interventions for adolescent sex offenders (ASOs) and children with

sexual behavior problems (CSBPs). Many ASOs and CSBPs can be appropriately treated through

community-based services. Others must be removed from their home in order to provide for their

individual treatment needs and to protect the safety of other family members and the communityat-large. Suggestions will be provided on how to structure the decision-making process when

determining the service needs of adolescents and youths who have engaged in illegal sexual

behaviors.

Materials:

Handout 1: Levels of Care for Adolescent Sex Offenders and Children with Sexual

Behavior Problems

Handout 2: Matching Youth Reoffense Risk to Levels of Restrictiveness

Handout 3: Linking Case Factors and Treatment Program Types for Adolescent Sex

Offenders and Children with Sexual Behavior Problems

NCSBY Fact Sheet: Risk Assessment of Adolescent Sex Offenders

NCSBY Fact Sheet: Adolescent Sex Offenders: Common Misperceptions vs. Current

Evidence

NCSBY Fact Sheet: Clinical Assessment of Children with Sexual Behavior Problems

Overhead projector or Laptop computer and LCD projector if available

Resources: For additional help and information on this program you may contact The

National Center on Sexual Behavior of Youth, Center on Child Abuse and Neglect, Department

of Pediatrics University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center 940 NE 13th St, Rm 3B-3406

Oklahoma City, OK 73104-5066. Phone: (405) 271-8858; Fax: (405) 271-2931.

Objectives:

At the conclusion of this session, participants will be able to:

1

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

Identify the ten guiding principles for determining the placement needs of ASOs and CSBPs;

Describe the service Continuum of Care for ASOs and CSBPs;

Identify the methods of sexual reoffense risk assessment and describe how reoffense risk

factors influence placement decision-making;

Describe the importance of prioritizing intervention needs for ASOs and CSBPs and

incorporating this information into placement decision-making;

Identify common factors that drive sexually abusive behavior in ASOs and CSBPs and

describe their relevance to placement decision-making

Determine the relevance of such youth factors as personal strengths, sex, proximity to the

victim/potential victim, and developmental disabilities to placement decision-making.

Advanced Preparation:

Review session material.

Prepare adequate number of handouts and NCSBY fact sheets.

Check availability and functioning of AV equipment

Outline:

I. Introduction

II. Ten Principles of Placement Triage Decisions for ASOs and CSBPs

A. General Principle I—Decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis.

B. General Principle II—The youth’s cultural identity should be considered in placement

decision-making.

C. General Principle III—The youth’s behavior, strengths, and problems are more

important than an administrative classification.

D. General Principle IV—The youth should be placed in the least restrictive level of care

that is consistent with community safety and victim welfare.

E. General Principle V—Placement decisions should be reassessed over time.

F. General Principle VI—Both sexual and co-morbid or non-sexual issues are important

considerations.

G. General Principle VII— Decision-makers should be knowledgeable about and have

expertise in child and adolescent development.

H. General Principle VIII—A group of professionals should be involved in the decisionmaking process.

I. General Principle IX—Decisions should be made with objectivity, fairness, and

candor, and should be based on current scientific knowledge.

J. General Principle X—Treatment services should meet high levels for standards of

care.

III. The Continuum of Care

A. Prevention Program Level

B. Outpatient Program Level

C. Intensive Community-Based Level

D. Foster Home and Independent Living Level

E. Day Treatment Level

F. Group Home Level

2

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

G. Short-Term Intensive Inpatient Level

H. Unlocked, Staff-Secure Residential Level

I. High Security Lock-Down Level

IV. Five Questions to Ask in Making a Placement Decision, How to Answer Them and What

They Mean

A. What is the level of current risk for sexually harmful behavior in ASOs?

1. Risk Assessment Approaches

2. Using Risk Estimates

3. Matching Risk to Level of Restrictiveness

B. What are the intervention priorities?

C. What factors are driving the behavior?

D. What can realistically be expected to change?

E. What are the youth’s strengths to consider in placement decisions?

V. Additional Placement Issues

A. In-Home Victim or Potential Victim Situations

B. Special Needs Populations

C. Benevolent Triage

VI. Summary

Introduction

When adolescents have committed sexual offenses or children are discovered to have

highly inappropriate, aggressive, or victimizing sexual behaviors, decisions must be made.

Family members, child protection staff, juvenile justice personnel, judges, treatment providers,

and others often face decisions about the type, intensity, and location of intervention needed.

Often, these decisions involve choosing between different levels of care (e.g., community-based

or residential) and choosing among different types of intervention approaches.

These guidelines are intended to provide some structure and suggestions for the decisions.

Should be used to help those involved in the decision process think through the options. The

guidelines are not a replacement for case-by-case professional judgment or due process

procedure. The structure and many of the suggestions in these guidelines are based on inferences

drawn from clinical work and rigorous scientific study, these guidelines should be thought of as a

set of working assumptions that are subject to testing against emerging data. Because treatment

of ASOs and CSBPs is a rapidly developing field of study, decision makers should be aware of

the latest findings and research in this area.

These guidelines are designed to address questions about level of care, and placement, are

focused on the goals of meeting youth’s service needs. Preserving the safety of the community,

and respecting the welfare of the victim, and these goals are viewed as consistent with the main

priorities of the juvenile justice and child protection systems—rehabilitation and community

safety. Decisions about placement made in the service of other priorities, such as for punishment

purposes, cannot be well integrated into a services-oriented triage system. Although punishment

priorities exist and may be germane in some cases, these guidelines have focused on community

and victim safety, and service needs.

It is recommended that placement decisions for ASOs and CSBPs be guided by ten

3

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

general principles:

General Principle I—Decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis.

It is well established that ASOs and CSBPs are diverse populations. That is, there is no

single profile or pattern of behavior or no single set of characteristics or background that describe

these youth, and consequently no single one-size-fits-all approach to intervention or case

disposition will be appropriate for all cases. Decisions about level of care, removal from the

home in cases of sibling abuse, placement options, treatment programs, and related matters

should be made on a case-by-case basis. This is the core rationale for the practice of placement

triage.

General Principle II—The youth’s cultural identity should be considered in placement decisionmaking.

A good ‘fit’ between the service model, level of care, and the youth’s culture may be a

critical component of selecting the optimal case approach. Youth from some cultural groups may

not respond well to unfamiliar or culturally incompatible approaches. For many youth, culturally

based intervention practices may need to be considered as an alternative to or in combination

with standard treatment approaches. For example, traditionally oriented Native American youth

may benefit by including traditional healing practices or traditional practitioners in the overall

intervention plan. Treatment providers ideally should have some familiarity with the cultural

identities of their clients, and the traditions and belief systems of those cultures. It is important

to assess cultural identity on a case-by-case basis. Cultural identity is not always synonymous

with race or ethnicity. For example, a Hispanic youth’s cultural identity may derive from

Mexico, from Puerto Rico, or from Los Angeles, and each of these cultural identities might be

distinct from the others.

General Principle III—The youth’s behavior, strengths, and problems are more important than an

administrative classification.

Level of care and intervention decisions are most appropriately based on the youth’s

behavior, psychological make-up, and social ecology, and not on the youth’s administrative

classification. Because assessing behavior, psychological status, and social ecology are critical, it

is recommended that triage and placement decisions include information from professionals

qualified to assess these areas. Administrative classification alone (e.g., adjudicated offense

category, listing as a alleged perpetrator in a child maltreatment report) may be misleading.

Some youth might be administratively classified as sex offenders or abuse perpetrators, but might

not have any of the typical problems often targeted in specialized treatment programs. For

example, a youth who was adjudicated on the basis of participation in a group “mooning”

incident might share few issues or intervention needs in common with youth typically seen in sex

offender treatment programs. Conversely, just because a youth might be adjudicated for a nonsexual offense does not necessarily preclude the need for involvement in some level of sex

offender intervention. For example, a youth adjudicated for breaking and entering, where the

offense involved stealing undergarments for sexual purposes, might have clear needs for sex

offender specific services.

General Principle IV—The youth should be placed in the least restrictive level of care that is

4

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

consistent with community safety and victim welfare.

Given a continuum of placement options, youth should receive services in the least

restrictive option available that is consistent with their needs and with community safety and

victim welfare. At present, there is some consensus among treatment professionals that most

ASOs and CSBPs can be served in community-based or outpatient programs (ATSA, 19). Youth

should be placed in more restrictive levels of care only when it is clear that the youth requires

this level of care or when a lower level of care would clearly compromise community safety or

victim welfare.

Level of care decisions should consider the potential risks and benefits inherent in more

restrictive placements. It is not recommended that decisions be made on a “better safe than

sorry” basis given that there are always risks involved in a decision to utilize a more restrictive

level of care. Placement in more restrictive levels of care has some intrinsic benefits. More

restrictive settings provide closer supervision, greater structure, more security, and intensive

services. Conversely, more restrictive placements may impair normal social and relationship

development, lead to subsequent institutionalization, run the risk of increasing future delinquent

behavior by socializing youth into delinquent subcultures, and compromise family ties. In within

family sexual abuse cases, children who were victims may have a variety of reactions to the

removal and placement of their sibling in a more restrictive level of care. In some cases, these

children may suffer distress if their abusive sibling remains in the home. In other cases, the

children may suffer distress related to their sibling’s removal from the home and the loss of a

sibling relationship. These issues need to be evaluated on an individual case-by-case basis and

not based on broad assumptions such as, “Perpetrators should never be left in the home with their

victims,” or “Families should always be preserved.”

The need for intensive services and secure containment, although often related, should be

evaluated separately in placement decisions. In some cases, a need for high-intensity services but

not for high-security containment may be met in high-intensity community programs. However,

when youth pose an acute, ongoing risk to the community, restrictive placements should always

be given strong consideration.

In addition, system-wide cost and cost-benefit factors must be considered, and decision

makers should consider the implications of their decisions for the overall service delivery system

as well as for the individual case. For example, over-utilization of more restrictive placements,

which are usually far more costly than lower levels of care, may deplete system-wide financial

resources and adversely affect the entire continuum of care. If the continuum of care fails to

provide services across various levels of restriction, professionals should advocate for the

development and efficient utilization of a full continuum of services rather than accepting service

levels that are not well matched to the youths’ needs and levels of risk.

General Principle V—Placement decisions should be reassessed over time.

The status of ASOs and CSBPs may change, either for the better or for the worse, over

time. Consequently, it is critical that triage decision-making be an ongoing process. Youth in

more restrictive levels of care can and should be moved into less restrictive settings as their

status improves and as they demonstrate competency. Conversely, youth in less restrictive levels

of care may require more intensive or more restrictive interventions if their condition deteriorates

or if their family or social ecology becomes problematic despite appropriate efforts to maintain

5

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

the viability of a less restrictive level of care.

General Principle VI—Both sexual and co-morbid or non-sexual issues are important

considerations.

Placement decisions and service needs are determined by many factors. Sexual behavior

is an obvious and critical factor to be considered. However, in some cases, intervention

decisions should be based largely or even primarily on a set of non-sexual or co-morbid factors,

irrespective of the seriousness of the sexual behavior or sexual problems. In some cases, these

non-sexual factors are the first priority. For example, youth with acute psychosis may require

services that focus first on stabilization of their psychotic symptoms, and it could be

counterproductive to place these youth into a sex-offender program with little or no psychiatric

resources.

Some generally delinquent sex-offending adolescents may require services that focus

heavily on targets such as decreasing delinquent peer affiliations and promoting prosocial

affiliations, increasing school involvement, increasing general parental supervision, and

managing substance use. Vocational, educational, or recreational development may be important

to consider. CSBPs who have significant posttraumatic stress symptoms general childhood

behavior problems may primarily need services that focus on these problems.

It is important to take a holistic perspective of the youth’s needs and to balance sexual

and non-sexual issues on an individual case-by-case basis. Placement options should include,

but not be limited to, specialized sex-offender programming. The practice of excluding

adolescent sex offenders, as a broad group, from entire classes of services or requiring these

youth to be served exclusively in sex-offender specific programs is not supported by the available

evidence and should be actively discouraged. This is especially true for CSBPs.

General Principle VII— Decision-makers should be knowledgeable about and have expertise in

child and adolescent development.

Because ASOs and especially CSBPs are distinct from adult sex offenders, expertise

based on assessing and treating adult sex offenders does not qualify a decision-maker to deal

with the sexual, and especially non-sexual issues presented by teenagers and children. Placement

and intervention decisions should be based on a specific knowledge of ASOs and CSBPs and

specific expertise in general child, adolescent, and family work. With young CSBPs, primary

expertise in child or pediatric mental health is essential. Services to children and adolescents

should be in programs that are appropriate to their development and should not mix disparate

developmental levels. For example, with very few exceptions, preadolescent children should not

be placed in programs with older adolescents and adolescents should not be placed in programs

with adults. This is especially the case in residential programs where mixing disparate

developmental levels carries risk for victimization. Similar issues must be considered with

making residential placement decisions for developmentally challenged individuals.

Developmental issues should also influence decisions about the duration, intensity, and

restrictiveness of care. For example, most CSBPs, will be placed in shorter-term and less

restrictive levels of care than ASOs.

6

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

General Principle VIII—A group of professionals should be involved in the decision-making

process.

Using teams to make placement decisions has several advantages. Team members can

obtain information from a variety of sources that may not be fully available to a single individual

and will combine a range of perspectives and expertise. Teams may be structured as formal

organized multidisciplinary teams, or as ad hoc and informal working relationships. Although a

well-selected working team is useful for decision making, not all teams function or work together

well, and the potential for personal conflicts or domination by extreme agendas must be

recognized and managed in order for teams to function most effectively. Although placement

recommendations or decisions can be made by individuals with adequate expertise, involvement

in team decision-making, whether formal or informal, should be strongly considered.

General Principle IX—Decisions should be made with objectivity, fairness, and candor, and

should be based on current scientific knowledge.

Placement and intervention decisions should be strongly rooted in a clear understanding

of the available empirical scientific literature on ASOs and CSBPs. Objectivity and reliance

upon well-supported models and empirical data are the hallmarks of professional triage

assessment and decision-making. As in any forensically relevant assessment, professionals

should take care to avoid over-reliance on “clinical impressions,” “intuition” or other procedures

with limited predictive validity.

Professionals should make their triage decisions based on the most complete, objective,

behavioral history available, and minimize reliance on tests or measures with no demonstrated

predictive validity for placement purposes and with the population in question. It is

recommended that decision makers disregard information that may decrease accuracy. For

example, various projective personality tests might be used by some clinicians for generating

hypotheses for treatment, but would be of little use in making a good decision about the level of

care a youth needs.

Some estimate of re-offense risk is generally part of making placement decisions, and

these risk estimates should be made with a full understanding of the basic scientific principles of

risk prediction (e.g., influence of base rates, sensitivity and specificity on rates of false positive

and false negative prediction, etc.). The decision can be assisted by utilizing relevant actuarial

systems or empirically-based risk assessment instruments as these become available.

Assessments of risk should begin by referencing established research estimates of reoffense rates

among the group in question rather than relying on clinical impressions or untested assumptions

about reoffense rates.

Placement decisions should be fair. In other words, they should not be biased by

irrelevant personal factors which have no predictive validity and that might disadvantage

particular social or cultural groups. For example, it has been found that African-American youth

in the juvenile justice system are more likely than white youth to be placed in secure correctional

facilities rather than community-based programs even when their behaviors are comparable.

Placement recommendations and decisions should be made candidly. That is, the

objective facts supporting why one level of care is recommended and why another is not, should

be clearly stated to all concerned. Both corroborating facts and potentially contradictory facts

should be made explicit.

7

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

General Principle X—Treatment services should meet high levels for standards of care.

Triage decision-makers should favor services with a) empirical support for effectiveness

(i.e., a body of well-controlled, rigorous, randomized clinical trials); b) an accepted theoretical

base; c) grounding in good clinical practices and ethical standards; and d) minimal demonstrated

or likely adverse effects. If rigorous empirical support for effectiveness is lacking (which is

currently the case for most standard ASO and CSBP interventions), decision-makers may select

treatments based on general professional consensus, provided these treatments meet criteria b),

c), and d). Triage decision-makers should be extremely cautious about recommending services,

treatments, or programs that are based on novel theories, that involve unusual or extreme

procedures, and that have potential for harm (e.g., “rebirthing” or “holding” therapies; memory

recovery therapies; shame-based interventions; aggressive and highly confrontational or punitive

interventions, etc.). At a minimum, treatment service providers should be licensed appropriate

for their discipline and treatment facilities should be accredited by an appropriate accrediting

body. It is desirable for treatment providers serving ASOs and CSBPs to maintain affiliations

with professional organizations designed to address this specialty area.

The Continuum of Care

In practice, triage requires that some continuum of care exists. Unless there is more than

one option from which to choose, there are no decisions to make, and the number of options

comprising the continuum directly contributes to the ease or difficulty of making placement

decisions. For example, if only outpatient group therapy or inpatient hospital levels of care are

available, then deciding can be very difficult for those youth where community-based group

therapy seems insufficient, but where inpatient hospitalization seems more restrictive than

necessary. A continuum that has two additional levels of care, such as intensive communitybased and therapeutic foster care, might make the decision far easier.

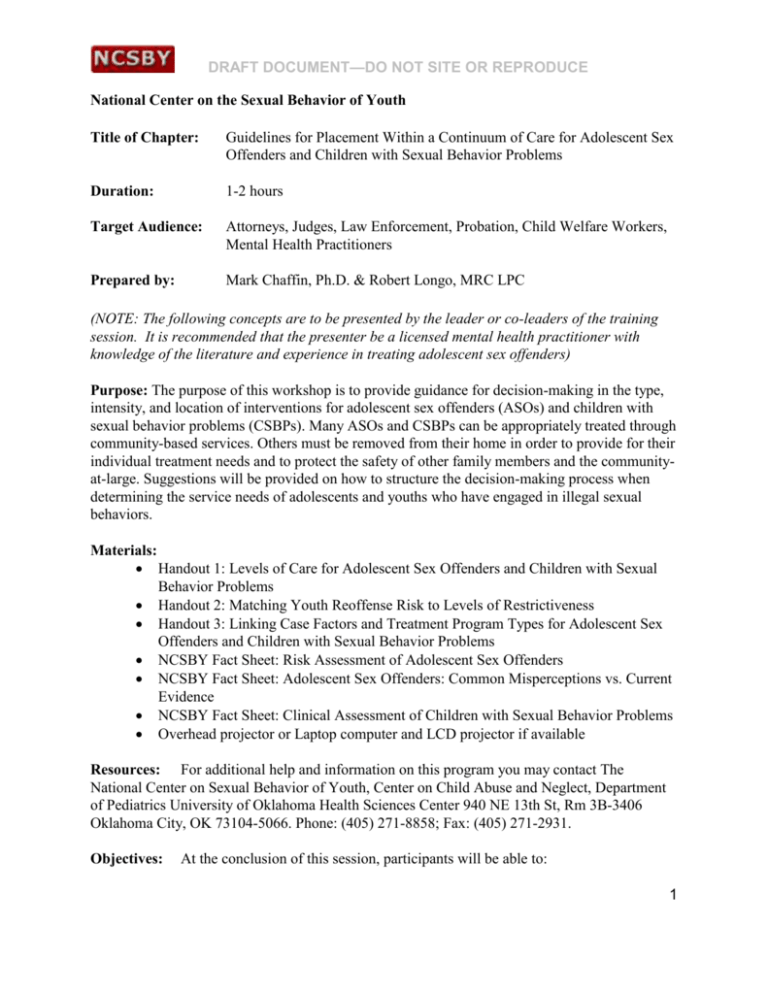

Given that less restrictive levels of care are appropriate for larger numbers of youth, a

continuum of care can be seen as a pyramid organized from least restrictive options at the bottom

to most restrictive options at the top. This is depicted in Handout 1, with corresponding

examples of continuum points on the right and corresponding costs of care on the left.

(NOTE: Distribute Handout 1: Levels of Care for Adolescent Sex Offenders and

Children with Sexual Behavior Problems.)

Examples of Continuum Levels of Care1 (beginning with least restrictive):

1) Prevention Level2

1

This continuum does not include all existing, necessary, or desirable levels of care. 2 It is not exhaustive

and the points along the continuum may not accurately characterize a particular individual facility. In this

continuum, the prevention level describes services which would be appropriate across a range of children

and adolescents, including some identified case populations as well as general populations of youth

(primary prevention levels) and at-risk populations (secondary prevention levels). 3 For example, there

may be group homes that provide a much higher level of security than that described, or a juvenile

correctional facility may provide far more services than described.

8

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

a) Primary Prevention Programs

i) Example: Public and private school systems provide age-appropriate or educational

programs on human sexuality and human sexual behavior, including materials on

sexual assault and child sexual abuse prevention.

b) Secondary Prevention Programs

i) Example: For youth identified to be at-risk for sexual behavior problems,

community-based mental health or delinquency programs provide a short-term, age

appropriate, collateral psycho-educational module on human sexuality and human

sexual behavior, including detailed material on sexual assault and child sexual abuse

definitions, consequences, and strategies for identifying, avoiding, and coping with

risky sexual behavior situations.

ii) Example: Self-help and "hot-line” programs are public health model programs that

provide information and support to at-risk or undetected case populations; they

typically provide information, educational materials on self-management strategies,

anonymous call-in support, and linkage to intervention services (e.g., the StopItNow

model).

iii) Example: Big-Brothers/Big-Sisters programs; although not designed specifically to

prevent sexual behavior problems, these types of programs have been demonstrated to

broadly prevent behavior and delinquency problems among at-risk children and youth.

2) Out-patient Program Level

a) General Clinic-based Services

i) Example: Outpatient individual, group, or family therapy providing traditional

mental health services (variable focus, model, and duration)

ii) Example: Parent-training programs for child behavior problems (often around 16

sessions)

iii) Example: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety, depression, or traumatic stress

symptoms (often around 12-24 sessions)

b) ASO or CSBP Specific Outpatient Programs

i) Example: Outpatient ASO or CSBP group treatment programs. This is probably the

single most utilized mode of service and is one of the most common triage

dispositions. Program duration is usually a few months for CSBPs and from 12 to 18

months for ASOs. These programs may include individual and family sessions in

addition to group sessions. Many ASO or CSBP group programs are based on

cognitive-behavioral models and may include modules generally based upon relapseprevention theory; increasing self-monitoring of behavior; and understanding patterns,

consequences and strategies for managing inappropriate sexual behavior, etc. A

number of published manuals, workbooks, and guides are available for implementing

these programs. Parent or caretaker involvement is generally recommended or

required. Youth receiving outpatient services usually live at home, with other family

members, or in a foster home.

3) Intensive Community-Based Level

i) Example: Multi-systemic Therapy (MST) or Functional Family Therapy (FFT).

These are short-term (e.g., 4 months in some models), highly intensive (up to daily in9

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

home contacts, small caseloads, and 24 hour interventionist availability) interventions

that are designed for seriously delinquent, multi-problem adolescents and their

families. Both approaches emphasize working with and through families, and both

focus on obtaining immediate and maximal behavior change on assessment-driven

goals. Youth receiving intensive community-based interventions usually live at home

or in a foster home. Both MST and FFT are based on empirically evaluated protocols

and both have been demonstrated to reliably reduce violent, delinquent, and substance

abusing behaviors and to have strong cost-benefit ratios. Specific training and

certification is involved for using these protocols. There is some specific evidence to

support the efficacy of MST with ASOs.

4) Foster Home and Independent Living Level

a) Foster Home

i) An actual home where the foster parent(s) normally reside which will accept a few

children or youth to live in the home. Foster homes are not facilities and do not have

staff. Foster parents are usually lay individuals who have been screened and provided

with brief basic training. Youth in foster care attend school in the community and

live a more normal family life. Foster homes are not physically secure and cannot

realistically provide constant supervision. Foster care services are usually supervised

by an agency that provides foster parent training, placement monitoring and case

management, and that assumes responsibility for youth in the agency’s foster homes.

Youth in foster homes often participate in outpatient or sometimes in intensive

community-level services. In general, foster parents accepting CSBPs and ASOs

should be aware of the potential sexual behavior problems these youth may have, and

not CSBPs and ASOs should not be placed in homes with vulnerable individuals

(e.g., younger children).

b) Therapeutic Foster Home or Specialized Community Home

i) Example: These are foster homes where the foster parent(s) have received more

extensive training, including specialized training in managing children with special

emotional or behavioral needs. In some cases, the training may include special

training in managing youth with sexual behavior problems. Agency supervision of

therapeutic foster homes may be closer, and there may be higher expectations for the

foster parent(s) to collaborate with other service providers or to be part of a treatment

team. Specialized community homes are similar to therapeutic foster homes, except

that they have a few more youth (perhaps 4-6) in a normal home environment with

foster parents, as distinct from group homes, which are generally larger and facilities

with staff.

c) Independent Living Home

i) Example: A small, semi-structured home-like facility, often in a residential

neighborhood, housing a small number of older adolescents under supervision. The

level of supervision and structure in independent living facilities may be less than that

of group homes. Residents of independent living facilities are often older teens who

do not have a viable family situation, but who are appropriate for a community level

disposition and who need to acquire basic independent living skills under some

supervision prior to living on their own. Some have previously been in more

10

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

restrictive settings. Independent living facilities often emphasize youth completing

their education, obtaining employment, and learning basic household and money

management skills.

5) Day Treatment Level

i) Example: A program associated with or physically attached to a residential or

inpatient psychiatric program, where youth participate in the treatment milieu and

programming but live in the community and return home in the evenings and on

weekends. Day programs usually incorporate specialized classroom

schooling/vocational training and therapeutic components similar to those found in

residential programs. Day programs may have access to other inpatient or residential

treatment service components on site, such as access to psychiatric medication

management.

6) Group Home Level

a) Group Home

i) Example: A small, home-like facility, often in a residential neighborhood, housing a

group of delinquent adolescents with 24hour staff supervision. Group homes may be

locked at night and the activities of residents are highly structured and well

supervised; they are not physically secure facilities designed to contain youths;

provide constant supervision, or prevent escape. Group home residents may attend

school or hold jobs in the community, but typically there are rules that do not allow

them to move freely in and out of the facility. Group homes may provide on-site

counselors or offer on-site services such as group or family therapy or they may

arrange for those services off-site.

b) Sex-offender Specific Group Home

i) Example: A group home specifically for ASOs that includes specific sex offender

treatment programming. Sex-offender specific group homes may offer on-site sex

offender treatment groups and individual/family therapy, similar to that offered in

outpatient programs. Sex-offender specific group homes may supervise the

residents’ sexual behavior more closely and may have special rules related to

potentially sexual situations.

7) Short-term, Intensive Inpatient Level3.

a) General Psychiatric Inpatient Unit

i) Example: A locked psychiatric treatment unit in a hospital setting with 24-hour staff

coverage. Length of stay on these units can vary but is often a few weeks. These

units usually provide intensive, daily, multi-modal and multidisciplinary services

overseen by psychiatrists, including medical management of serious psychiatric

disorders such as severe depression, acute psychosis, or acute mania. Stabilization of

acute psychiatric symptoms is a common treatment goal for these facilities.

b) Sex-Offender Specific Short-Term Residential Unit

i) Example: A residential treatment facility with a short-term length of stay (e.g., 30

days) designed to stabilize sexual behavior problems, and other co-morbid problems,

3

These types of facilities are designated as less restrictive than residential treatment facilities based on

their shorter lengths of stay. However, the levels of security and restrictions on day-to-day freedom in

short-term, inpatient facilities may be greater than that found in residential type facilities.

11

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

complete initial sex offender assessment and treatment, and then link the youth with a

less restrictive follow-up program to complete treatment. These units may be

physically attached to other less restrictive levels of care within an agency or facility.

For example, youth exiting the short-term residential program may continue in

outpatient treatment with the same providers or treatment team.

8) Unlocked, Staff-Secure Residential Level

a) Therapeutic Boarding Schools and Similar Programs

i) Example: A year-round structured program with staff-supervised dormitories or

cottages designed to provide therapeutic, educational, recreational, and behavior

management services to children and adolescents who have long-standing emotional

and/or behavioral difficulties, but who are not have acutely psychiatrically ill.

Residents typically receive weekly individual/group/family therapy and periodic

medical or psychiatric services. The youth are usually restricted to the campus, but

may have “grounds privileges” based on behavior and treatment plan progress.

Lengths of stays in these facilities are often quite long-term. Some of these facilities

have specialized sex offender programs and/or sex offender specific cottages or

campuses segregated from other youth.

9) Secure Residential Facility Level

a) Locked Residential Treatment Centers

i) Example: A freestanding, locked, controlled-access unit, or a more controlled unit

within an overall residential campus where resident activities and movements are

controlled or monitored by staff on a 24-hour basis and there is a strong emphasis on

structure, intensive behavior management, and containment. These facilities provide

on-site schooling and frequent, intensive psychological or psychiatric services

delivered by on-site professional staff. These facilities often have seclusion and

restraint capacity and rely on behavioral systems or level systems to gain compliance

from residents.

b) Sex Offender Specific Locked Residential Treatment Centers

i) Example: A facility similar to the one described above which but exclusively accepts

ASOs and where the treatment model is heavily focused on sexual behavior issues.

These facilities typically provide high levels of supervision of any circumstances

where there is a possibility of sexual behavior (e.g., bathrooms or shower restrictions,

supervision of sleeping facilities at all times during the night, etc.)

10) High Security Lock-Down Level

a) Juvenile Detention

i) Example: A short-term facility for youth, usually regimented, highly controlled, and

providing little or no treatment. These facilities are similar to correctional facilities,

except that they are designed to maintain youth for short periods of time (from a few

days to a month or so), either while waiting further processing, or as an “attention

getter” or sanction related to behavior or motivation problems.

b) Boot Camp Facility

i) Example: Boot camps are moderate-term (e.g., six month), highly structured

residential programs generally modeled after military basic training. They emphasize

rigorous physical exercise, regimented activities, strict supervision and discipline, and

12

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

military drill. Some, but not all, boot camps emphasize aggressive confrontation, of

the youth. The level of physical security provided at boot camps can vary, although

many are highly secure facilities. Some boot camps are designed for sanction or “remotivation” purposes.

c) Juvenile Correctional Facility

i) Example: A juvenile facility with high security and multiple barriers preventing

escape. These facilities may provide some professional psychological or psychiatric

treatment services and may use a level system. Participation in school or GED

services usually is required for residents. Behavior change is often pursued via

control and application of sanctions. Staff members are typically security officers

rather than treatment or nursing staff.

d) Adult Correctional Institution

i) Example: An adult prison, which is similar in many ways to a juvenile correctional

facility. There is considerable variation among adult correctional institutions in both

their atmosphere and service availability. In general, however, adult correctional

institutions offer fewer rehabilitative services than juvenile correctional institutions,

house more serious and dangerous individuals, and have a greater emphasis on

physical security, containment, and control.

Five Questions to ask in Making a Placement Decision, How to Answer Them and What

They Mean

Question 1: What is the level of current risk for sexually harmful behaviors in ASOs?

There are currently three approaches to estimating risk for harmful behaviors: clinical

assessments, true actuarial systems, and empirically guided systems.

Clinical assessment relies on impressions from face-to-face interviews, reviews of basic

psychosocial history, and traditional psychological testing. This is the most common approach to

assessment, and is typical practice, in most psychological evaluations that are conducted in

forensic settings. Unfortunately, the predictive accuracy of clinical assessments has been widely

demonstrated to be quite poor (often no better than random chance). With ASOs in particular,

clinical assessments have been shown to over-predict risk relative to actual rates of sexual

recidivism. Clinical assessments may be valuable for answering other triage questions (i.e.,

identifying other severe mental health problems), but should not be used as the primarily tool for

estimating risk.

Actuarial systems are empirically derived and validated tools, usually based on objective

behavioral historical factors. True actuarial systems classify individuals into groups with known

probabilities for reoffense. For example, it would be possible to say, “a group of individuals with

a score of X on a particular actuarial system has an overall Y% chance of sexual recidivism over

the next 10 years.” Across a broad range of behaviors, actuarial systems are more accurate,

objective, and fair. True actuarial risk assessment systems exist and are the state-of-the-art for

adult sex offender risk assessment. Unfortunately, no comparable actuarial systems have yet

been developed for ASOs and CSBPs. However, the most basic of all actuarial systems is simply

to predict the mean risk for an overall group. For example, the overall detected sexual recidivism

risk for ASOs across studies is around 10%. Thus, without knowing anything else about an

ASO, the best initial estimate of his or her sexual recidivism risk would be 10% (given the usual

13

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

structure, supervision, and services provided).

Empirically guided systems are midway between clinical assessments and true actuarial

systems. There are empirically guided systems available for ASOs and it is recommended that

decision-makers acquire and use these tools. Examples of empirically guided systems include

the Juvenile Sex Offender Assessment Protocol (J-SOAP-II; Prentky & Righthand), the Estimate

of Risk of Adolescent Sexual Offense Recidivism (ERASOR-2; Worling & Curwen, 2001) and

the Protective Factors Scale (PFS; Bremer, 2001). These are described below:

Empirically guided systems select potential objective risk factors from the empirical

outcome literature. They differ from true actuarial systems in that there currently is not an

empirically derived scoring system and there are no known sexual recidivism probabilities

associated with particular combinations of items or scores for ASOs or CSBPs. Therefore, it is

not recommended that scores from any of these instruments be used. Empirically guided systems

are valuable for directing attention toward factors that are important and away from factors that

have little predictive ability. They should be used as guidelines for conducting a risk assessment,

but the ultimate significance of any given item or combination of items still must be determined

by the evaluator. Consequently, it is recommended that empirically guided systems be used only

by professionals with adequate experience in the science of risk prediction and ASO or CSBP

assessment.

The first step in empirically guided risk assessment is to estimate the average risk for the

entire group (e.g., ASOs or CSBPs). Based on the current literature, that estimate would be

around 10% for ASOs and 15% for CSBPs. Some youth who reoffend may remain undetected,

so the actual number may be higher, although the extent to which that is true is unknown.

Because this rates is low, we could predict that 101% of ASOs will have further illegal sexual

behavior, (assuming the youth receives typical interventions and supervision conditions), and we

would be correct in that prediction 90% of the time. This is important to remember because it

suggests that there should be fairly persuasive evidence available before it can be legitimately

concluded that a given youngster is “high risk” to reoffend.

After beginning with the overall group risk estimate (ASO=10%), this estimate can be

adjusted up or down depending on the number and importance of the risk factors identified using

a tool such as the JSOAP-II, ERASOR-2, or PFS. Note that adjustments up or down should be

made from what would be expected for an “average” ASO on these instruments. An average

ASO would be expected to have some number of risk factors. Finally, it is important to note any

dramatic or exceptional factors that might dictate an increase from the overall average risk or the

tools. Very rare factors, such as a statement of intent to re-offend, often are not included on risk

instruments. However, if an adolescent made a credible statement of intent to re-offend or was

showing clearly out-of-control sexual behavior, this would indicate high-risk status regardless of

a low score on a risk assessment tool. It is important to note that risk assessments for ASOs and

particularly for CSBPs must focus on the youth’s family and social ecology and not be limited to

individual child or adolescent characteristics. Youth who might be higher risk in one

environment (e.g., no supervision, no appropriate adult involvement or support, easy access to

potential victims) might be lower risk in another setting (e.g., high supervision, involved and

capable adults, etc.).

Using Risk Estimates—Immediate Steps That Might Reduce Risk. Risk is particularly

important for determining how restrictive a level of care is needed. Before deciding, it is first

14

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

important to look for any immediate steps that might be taken to modify the assessed risk. For

example, if a youngster is assessed as high risk partially on the basis of poor parental supervision,

the first question to ask is, “Are there any alternative adults who can step in to provide adequate

supervision?” Or, if a youngster is assessed as high risk partially on the basis of having a

potential victim living in the same home, the first question to ask is, “Are there immediate steps

that can be taken to control unsupervised assess to the potential victim?” If a youngster is

assessed as high risk partially on the basis of significant ADHD symptoms, the first question to

ask is, “Can these symptoms be immediately reduced by treatment?” In many cases, the answer

to these kind of questions is “Yes,” and there may be immediate steps that will reduce the initial

risk estimate. If so, these steps should be recommended as clear prerequisites and the

recommended level of care can be based on how much risk is expected after the prerequisite

steps are taken and evaluated.

In other cases, the factors contributing to high risk may be difficult to modify or may not

be amenable to immediate interventions. Or, despite all immediate steps that might be taken, a

youngster may remain at high risk. In these cases, recommendations for a more restrictive level

of care are appropriate.

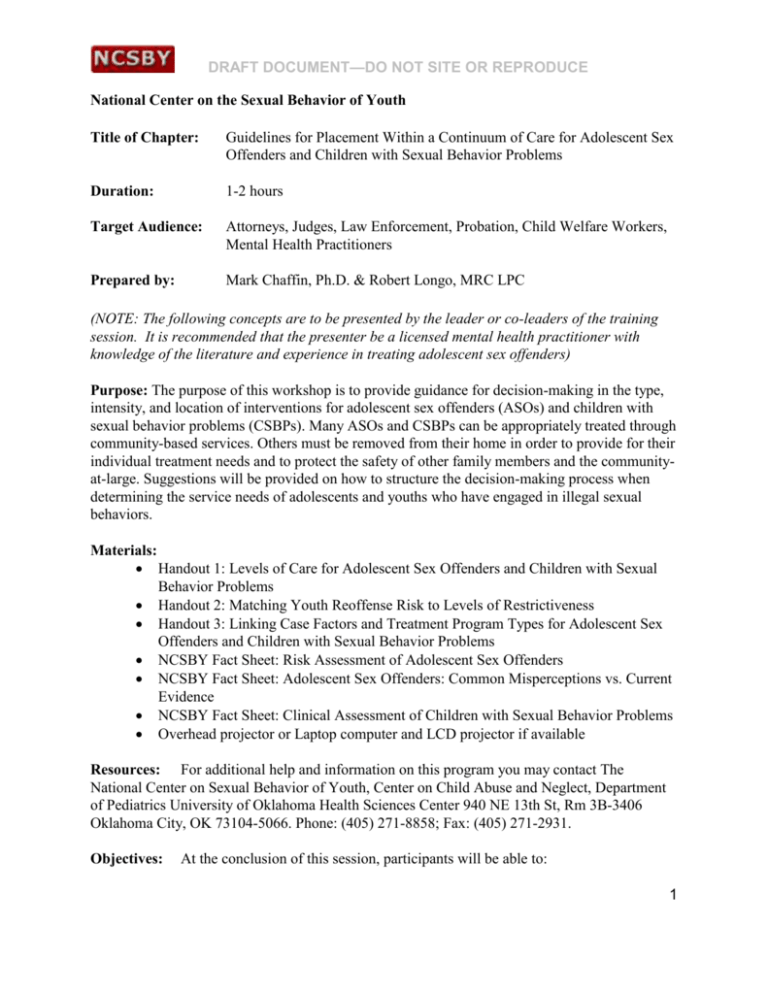

Matching Youth Reoffense Risk to Level of Restrictiveness

Handout 2 is a rough guide for matching levels of current risk (adjusted for any

prerequisite steps taken) and levels of restrictiveness.

(NOTE: Distribute Handout 2: Matching Youth Reoffense Risk to Levels of Restrictiveness.)

Question 2: What are the intervention priorities?

In addition to risk, triage decisions should be based on an evaluation of intervention

priorities. Some intervention or treatment needs are simply more important than others. ASOs

and CSBPs may be multi-problem youth or come from multi-problem families or environments.

In these cases, the number and variety of problems, may appear overwhelming and or to over

array of interventions may be prescribed in an effort to be comprehensive or intensive. This is

seldom a good idea. In general, interventions and treatments that focus on a limited number of

major, important target areas are as effective, or more effective, than attempts to provide an

intervention for every problem. Unfocused, over-prescribed approaches to intervention are not

only unproductive; they impose burdens on both clients and the service delivery system. It is

important to address major problems first and not everything at once.

Some paramount priorities are fairly obvious. For example, youngsters who are acutely

suicidal or who have acute medical needs require immediate intervention to insure their health

and safety, and this would clearly take priority over other issues and needs. Similarly, youth who

are homeless or who lack adequate nutrition or shelter require attention to these matters

immediately.

Serious mental health problems may be a high priority. For example, youngsters who

have serious psychotic symptoms, are severely depressed or manic, are clearly suicidal, or who

have continuous out of control explosive behavior may be unable to meaningfully participate in

ASO or CSBP treatment until these problems are treated and brought into some reasonable

remission. In these cases it makes little sense to pursue primary treatment for sexual behavior

15

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

problems until these other problems are managed. It is important to note that some facilities or

placements may not be equipped to manage serious mental health problems. For example, some

group homes or correctional facilities may have limited on-site expertise or resources to deal

with these problems and would not be good choices for acutely psychiatrically ill youth. In cases

where there are high-priority serious mental health problems, the triage decision should be

guided first by the availability of resources and expertise needed to deal with these problems

rather than the availability of specific treatment for sexual behavior problems, provided that

sexual behavior risk can be managed adequately in the psychiatric setting. Other sex-offender

programs (e.g., short-term inpatient programs) may have excellent resources for managing both

serious acute mental health problems and sexual behavior problems and may be good choices in

many of these cases. In making triage decisions about seriously psychiatrically ill youth, it is

critical that the placement decision-maker know specifically what psychiatric expertise and

services are available along their local continuum of care.

Sexual behavior is usually a significant priority in almost all ASO and CSBP cases, and

there is consensus in the practice field that the intervention plan should focus specifically on the

sexual behavior problem at some point. Specific services targeting sexual behavior will be a

component of most triage decisions and will usually be a major priority, although not the top

priority or the first-step recommendation in all cases. The exact format of these services and

programs can vary considerably. Group-based programs are very common. However, there are

no data to suggest that group-based programming is any better or worse than other approaches

(individual, family, ecological). Whether or not a program is sex-offender specific is

independent of its level of care or restrictiveness. Sex-offender specific or sexual behavior

specific services are adaptable across a range of levels of care, from outpatient clinic services to

maximum security facilities, and there may be more similarities than differences in the actual

content of these sex-offender services across the various levels of care.

Non-sexual behavior problems, including oppositional defiant or aggressive behavior

problems among CSBPs and or delinquency among ASOs, are also a high priority. Major

substance use disorders may be included in this category (or even higher in the event they reach

life-or-death severity). In general, the prevalence or recurrence rates for sexual problems.

Consequently, these problems are also a significant priority in many cases. Many of the most

effective interventions for childhood behavior problems and adolescent delinquency emphasize

strong family or family surrogate involvement. For example, behavioral parent training

programs such as Parent-Child Interaction Therapy are among the more effective interventions

for childhood behavior problems, and interventions such as Multi-systemic Therapy or

Functional Family Therapy are among the more effective interventions for adolescent

delinquency.

Many other problems might be moderate priorities or relatively low priorities. For

example, parent-child relationship problems might be considered as a moderate priority to target

at some point. Lower priority intervention needs might reflect life-enhancement goals, such as

self-understanding or improved self-esteem. Although these might be worthwhile goals to

pursue at some point, they will seldom be high priorities in making a placement decision.

Question 3: What factors are driving the behavior?

Decisions about level of care and type of intervention may depend on some assessment of

16

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

the etiology and driving factors involved in the sexual behavior. This is an area of triage

decision-making that is currently not well defined and is certainly not well standardized. There

are many theories and models of the factors that drive aggressive or victimizing sexual behavior

among CSBPs and ASOs, and consequently there may be variation in how intervention programs

approach the problem with any individual child. Finkelhor (1984) described a set of factors that

motivate sexually abusive behavior, and Johnson (1988) described a range of childhood patterns.

Typologies of ASOs have been described by Becker (1998), O’Brien and Bera (1986), and

others, many of which classify youth by their motivational pattern, and in some instances

prescribe intervention modes corresponding to the particular motivational pattern or subtype.

There are a number of common features across these typologies and models, and these features

are summarized below, as they may be relevant to making triage decisions.

Strong and recurrent sexual interests in unusual partners or unusual activities may be one

factor driving sexual misbehavior. For example, some ASOs may have emerging or established

sexual interest patterns focused on young children. Although this is a clear motivational factor

among some subgroups of adult sex offenders (i.e., adults with paraphilias), it remains unclear

and questionable how prevalent or important this is among ASOs. Some ASO treatment

programs are strongly based on this sexual deviancy model. Because concerns have been raised

that these types of programs might be counterproductive or even harmful for those youth who do

not have sexual deviancies, it is suggested that placement in these programs be limited to youth

where there is some independent assessment that the youth has significant problems with

recurrent and strong paraphilia-like interests and behaviors. These may include older adolescents

who have established patterns of behavior with unusual sexual targets (i.e., young children), or

who are assessed as having clear, strong, recurrent sexual arousal to young children. In cases

where there is clear-cut evidence of sexual deviancy, specific intervention for this problem is

recommended.

General delinquency is a common pattern among ASOs and most typologies include

some reference to youth who commit sex crimes as part of an overall delinquent behavior

pattern. Norm violating and victimizing sexual behavior has long been noted among the general

population of delinquent adolescent. Although some generally delinquent sex offenders also may

have recurrent sexual deviancy, many do not, and these predominantly delinquent youth may

engage in abusive sexual behaviors due to more general factors (impulsivity, poor judgment,

delinquent peer influences, etc.) that are unrelated to sexual deviancy. Other ASO programs are

more focused on general competency development, family involvement, peer relationship

development, decision-making, general behavior modification, and related factors. These

programs may be better choices for youth who do not have strong sexual deviancies. In other

cases, where the level of non-sexual delinquency is high and there is not evidence of strong

sexual deviancy, more intensive delinquency oriented models, such as MST or FFT should be

considered.

Other youth, particularly young, immature adolescents, may engage in sexually abusive

behavior motivated by sexual curiosity or experimentation. Some of these youth may not have

acquired a habitual interest in sexually abusive behavior and may be otherwise non-delinquent.

Although these youth may have a range of less severe identified problems (e.g., learning or

attention problems, social skills problems, family problems), they often do not have any serious

mental health disorders. Programs focused on competency development and decision-making

17

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

and sexual behavior management might be considered for many of these youth.

A few youth may participate in sexually abusive behavior under coercion from an older

person or as a direct consequence of a major mental illness. For example, a young adolescent

boy may be coerced by an abusive parent to perform sexual acts on a younger sibling, or an

adolescent may commit a sex crime during an acute psychotic episode. In these cases, the

primary driving factors for the behavior may be so unique that the intervention plan will not

include sex-offender specific treatment at all. Related to this, there are some youth whose

behavior is strongly influenced by peer pressure (e.g., a young adolescent who is persuaded by a

group of peer to engage in a single incident of sexually inappropriate behavior), and intervention

in these cases may focus more on assertiveness and education about sexual behavior, potential

consequences, and coping with peer pressure.

It is generally accepted that some CSBPs are responding to recent personal experiences

with sexual abuse or exposure to explicit sexuality. Some CSBPs present with significant sexual

trauma symptoms, and others exhibit behavior that reflects sexual experiences they have had. In

many of these cases, triage may favor interventions that, while having a sexual behavior focus,

provide considerable emphasis on reducing sexual trauma symptoms. More structured

treatments have been found to be somewhat better for more highly traumatized CSBPs. General

behavior problems also are common among CSBPs, and in these cases triage decisions may favor

interventions that include a focus on teaching parents effective child management skills. Again,

in general, triage for CSBPs will typically favor interventions that are shorter-term and less

restrictive than interventions for ASOs. Parent/caretaker involvement, which is important in

ASO intervention, is seen as critical for CSBP intervention and should be a high priority.

Consequently, it is suggested that triage decision-makers strongly favor levels of care for CSBPs

where parent/caretaker involvement is an integral part of the intervention.

Handout 3 depicts some possible triage linkages between possible case factors and

treatment program types.

(NOTE: Distribute Handout 3: Linking Case Factors and Treatment Program Types for

Adolescent Sex Offenders and Children with Sexual Behavior Problems.)

Question 4: What can realistically be expected to change?

Prognosis is an important factor in placement and service decisions. Simply put, some

problems or factors are more amenable to change, modification, or compensation and others are

far less pliable. Triage decision makers select interventions based on a reasonable expectation of

benefit and favor priorities that are amenable to rapid and substantial change over similar

priorities that are not. Some priorities and factors may not be amenable to change, but they may

be amenable to compensation. For example, a youngster may have dyslexia that impairs his

ability to participate in a treatment program with written assignments, but modifying the format

of the curriculum or providing a reading coach may compensate this for this.

There are a number of common coexisting problems that have a favorable prognosis for

prompt change, assuming they are matched to the correct intervention. For example, ADHD

often responds rapidly and favorably to stimulant medication. PTSD symptoms respond rapidly

to short-term, structured cognitive-behavioral protocols. Childhood oppositional and defiant

behavior responds substantially and rapidly to behavioral parent training approaches.

18

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

Other problems may require sustained intervention and have unpredictable success. For

example, drug or alcohol dependency responds to treatment but the response may require time

and there may be significant lapses over time. Serious delinquency problems may be reduced but

not always eliminated, and chronic family dysfunction may be improved but deteriorate later.

Other problems, despite their importance, may not respond well to the typical services

offered or may be intrinsically stable. For example, chronic poverty, mental retardation, or broad

social-environmental problems may be difficult or impossible to change through any

intervention. In these cases, triage decisions can focus on compensation and averting the worst

outcomes of these problems rather than attempting to eliminate them.

Question 5: What are the youth’s strengths to consider in placement decisions?

In addition to considering risk, problem priorities, driving factors, and prognosis, it is

important to base placement decisions to some extent on the available strengths present in a

youngster and his or her family. For example, the presence of a committed and motivated parent

or parent substitute may compensate for any number of problems. A youngster who has friends

and a commitment to academic success may be able to overcome obstacles despite other

disadvantages.

Finally, it is important to consider motivational strengths. For example, a youth with few

problems but who denies his or her sex offense and has no interest in treatment despite

overwhelming evidence of guilt and need, may do worse in a lower level of care than a youth

with more problems but who admits and is motivated to participate in treatment.

Additional Triage Issues

In-home Victim or Potential Victim Situations. In cases of sibling or other in-home abuse, there

is considerable controversy surrounding the issue of removing ASOs or CSBPs from the home or

returning them to the home. There are those in favor of always removing abusive youth in these

cases (or alternately and less desirably, removing the victim child), and those never permitting

the reunification of abusive and victimized children, and those who make recommendations on a

case-by-case basis and favor reunification in most cases. Unfortunately, there is little empirical

data to guide decision making in these cases. It appears that the diversity of the ASO and CSBP

populations, the diversity of family environments involved, and the diversity of victim feelings

and needs in these cases is so great that a single approach to making decisions about removal and

reunification is not the best approach. In cases where risk is low, the family environment is

adequate, and the victim is emotionally intact and would be distressed by the loss of a sibling

relationship, it may be desirable for the family to remain intact with appropriate supervision and

treatment intervention. The value of preserving the integrity of family connections and family

living may be especially important to consider for CSBPs. In other cases, considerations of risk

and the welfare of the victim may be so acute that family preservation or reunification is simply

not viable. Regardless, it is suggested that these decisions be made on a case-by-case basis and

based on a thorough assessment of the entire circumstances. In some cases, it may be necessary

for abusive youth to be removed in the interim while this assessment is being conducted.

Special Needs Populations. Certain populations, such as female ASOs or developmentally

disabled ASOs, may not be adequately served within an existing continuum of care simply

19

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

because the population is comparatively small. Often placement decision-makers must choose

between a specialized program that is more restrictive than needed and/or located at a great

distance from the youngster’s home and family, and a non-specialized alternative. If risk is high

and a more restrictive level of care would be the first choice regardless of availability, then

distance from home may be less important than the need for appropriate containment and

provision of specialized treatment. However, risk will probably not be this high in the majority

of these cases, and it may be counterproductive to remove a child to a more restrictive level of

care than is needed, especially if it is located at a great distance from home, simply in order to

provide a particular intervention. In these cases, a generally qualified local provider might be

identified and arrangements made for that provider to obtain remote consultation or mentoring

from an experienced expert or program serving the special needs population. In addition, it is

important to note that some intervention programs, especially those that do not rely on group or

aggregate treatment approaches, may be more readily adaptable to diverse populations. For

example, intensive community based ecological models may be especially adaptable to the

individualized needs of these cases.

Benevolent Triage. On occasion, there may be unique circumstances that dictate a triage

recommendation that would not otherwise be appropriate. ASO or CSBPs may occasionally be

controversial in their neighborhoods, communities or schools and may be subject to social

stigma, threats or violence. On occasion, placement decision-makers may opt to recommend a

more distant or restrictive placement than would be dictated solely by the youngster’s assessed

status, simply in order to remove the youngster from a bad situation and allow some time and

space for circumstances to improve. Or there may be cases where a youngster might be linked

with an unnecessary service or program simply because the consequences of not accepting the

youngster would clearly be worse than any risks from unnecessary treatment. For example, a

youngster might be accepted into an outpatient sex-offender program on the basis of behavior

that normally would not meet the threshold for requiring sex-offender treatment if it was clear

and unavoidable that the youngster would otherwise be sent to an even more inappropriate

placement.

Summary

These guidelines are offered to assist professionals in the triage decision-making process.

Triage is viewed as an individualized, case-by-case process where risks, problems, driving

factors, prognosis, strengths, and the context of a case are combined and weighed in order to

arrive at a dispositional recommendation that balances the needs for rehabilitation, community

safety, victim welfare, and family integrity. Although empirically tested placement guidelines

and specific protocols may be available in the future, considerable work remains to be done

before any standardized or well-supported system is available. These guidelines are intended to

serve as a starting point for framing these decisions. Alternative frameworks, embodying

alternative assumptions, may be equally viable, and it is anticipated that, as knowledge develops,

some of the suggestions made in these guidelines will be supported and others will change over

time.

20

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

References

Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers (ATSA). (2000). The effective legal

management of juvenile sex offenders.

Becker, J. (1998). What we know about the characteristics and treatment of adolescents who

have committed sexual offenses. Child Maltreatment, 3, 317-329.

Bremer, J. (2001). Protective Factors Scale. St. Paul, MN: Project Pathfinder, Inc.

Finkelhor, D. (1984) Child sexual abuse: New theory and research. New York: Free Press.

Johnson, T. C. (1988). Child perpetrators – children who molest other children: Preliminary

findings. Child Abuse & Neglect, 12, 219-229.

O’Brien, M. & Bera, W. (1986). Adolescent sexual offenders: A descriptive typology. Preventing

Sexual Abuse, 1, (3), 1-4.

Prentky, R., & Righthand, S. (Undated). Juvenile Sex Offender Assessment Protocol II (JSOAPII) Manual.

Worling, J. & Curwin, T. (2001). The “ERASOR”: Estimate of Risk of Adolescent Sexual Offense

Recidivism, Version 2.0. Toronto, Canada: Sexual Abuse Family Education & Treatment

(SAFE-T) Program, Thistletown Regional Centre for Children and Adolescents.

21

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

Handout 1. Levels of Care for Adolescent Sex Offenders and

Children with Sexual Behavior Problems

•Locked Secure Facility

•Secure Residential Program

(more restrictive)

•Unlocked Staff Secure Level

•Group Homes

•Day Programs

•Foster Homes, Mentor

Homes or Independent Living

•Intensive Community-Based

Ecological Models (e.g., MST)

More Youth

(less restrictive)

•Outpatient Programs

•Prevention Programs

$$$$$ COST PER CASE $

Fewer Youth

22

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

Handout 2. Matching Youth Reoffense Risk to Levels of

Restrictiveness

•Extreme Risk-security or

flight risk, possibly

predatory

•Locked Secure Facility

Fewer Youth

(more restrictive)

•High Risk-can’t be in

community

•Secure Residential

Program

•Unlocked Staff Secure

Level

•Group Homes

•Day Programs

•Moderate Risk or Risk Due

Primarily to Environmental

(e.g. supervision)

•Some Risk

•Minimal Risk (perhaps not a

legal offense) or Prevention

Population

More Youth

(less restrictive)

•Foster Homes, Mentor

Homes or Independent

Living

•Intensive CommunityBased Ecological Models

(e.g., MST)

•Outpatient Programs

•Prevention Programs

23

DRAFT DOCUMENT—DO NOT SITE OR REPRODUCE

Handout 3. Linking Case Factors and Treatment Program

Types for Adolescent Sex Offenders and

Children with Sexual Behavior Problems

Case Factors

•Younger ASO, Limited

Sexual Problem

•Most CSBPs

•Limited Sexual Problem

•Judgment and competency

problems, but non-delinquent

Treatment Program

Shorter-Term

Outpatient Program

With Some

S.O. Focus

Outpatient

Competency Oriented

Sex-Offender

Program

•Limited Sexual Problem

•Generally Delinquent

Delinquency

Oriented

Program with Some

S.O. Focus

•Extensive Sexual Problem

(i.e. sexual deviancy)

More Extensive

Sexual Interest and

Sexual Behavior

S.O. Program

24