The concept of planning doctrine

advertisement

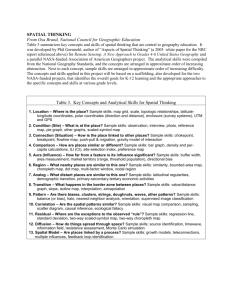

Roodbol-Mekkes, Petra H. & Arnold van der Valk & Willem K. Korthals Altes (2011), Netherlands Spatial Planning Doctrine in Confusion in the Twenty First Century. In: Environment and Planning A. Draft July 2011. Text accepted August 2011. Netherlands Spatial Planning Doctrine in Confusion in the Twenty First Century Petra H. Roodbol-Mekkes (petra.roodbol@wur.nl). Wageningen University, Land Use Planning Group Arnold J. J. van der Valk (arnold.vandervalk@wur.nl.), Wageningen University, land use planning group, Willem K. Korthals Altes (w.k.korthalsaltes@tudelft.nl), Delft University of Technology, OTB Research Institute for Housing, Urban and Mobility Studies, Jaffalaan 9, NL 2628 BX Delft. Abstract The Netherlands have a great international reputation for spatial planning. This has been explained by a strong national consensus about a set of interrelated and durable notions about spatial arrangements, appropriate development strategies and about the ways both are to be handled, a ‘spatial planning doctrine’. The context of planning has changed in the last 15 years, and many critics debate wheter Netherlands’ planning can still live-up with its reputation. This paper analysis the dynamics of the planning doctrine and concludes that spatial planning doctrine is still having its effect on planning practice. However, the dynamic planning context might wrench the planning doctrine out of joint if it does not open itself to a more dynamic evolution. Introduction Dutch spatial planning is held in high esteem by non-Dutch authors. This reputation is underlined by Faludi (2005), Needham (2007) and the authors. These success stories are predominantly based upon physical evidence in the man made landscape such as the preservation of farmland and the results of land and water development in orderly parcellation of city plans and field systems. Paradoxically, other Dutch scholars (such as, Hajer and Zonneveld, 2000; Bontje, 2003) tend to give a much more critical account of the state of the art and the challenges for the future. Critical accounts vision the gradual loss of 1 the old planner’s paradise due to an accumulation of recent changes in societal driving forces and flaws in the planning system in force. Recent successes such as the containment of open spaces in the Green Heart and in buffers between urban agglomerations are contested. The data do not speak for themselves. Within the Dutch context the criticism is quite real, and must be assessed seriously. Also to outsiders, the emergence of the perception of a ‘planner’s paradise lost’ (Bontje, 2003) may give unique and valuable insights into the conditions in which planning may work or fail. The long time undisputed position of spatial planning in the Netherlands is under attack and the strong influence that national planning once had on spatial development is weakening. Developments are increasingly in conflict with national planning policy, and national plans are losing grip (Hajer and Zonneveld, 2000). In addition, spatial projects are encountering more and more resistance from the public, and planning procedures are often notoriously slow. The criticism of spatial planning mainly concerned the lack of effectiveness of spatial planning in general and the national plans in particular. This criticism raises questions on whether the successful planning doctrine of the past is still relevant in spatial planning today. In this paper we will analyse the present position of the planning doctrine. First, we will introduce the concept of planning doctrine and present the indicators of doctrinal change as has been developed by Korthals Altes (1992). After this we will investigate the present position of the planning doctrine, using the mentioned indicators of doctrinal change. The paper finishes with a discussion and conclusion section. 2 The concept of planning doctrine Faludi and Valk (1994) have used the concept of planning doctrine to understand why the planning system has been so successful in guiding spatial developments in the Netherlands. Although strategic planning has changed in the past, the set of core ideas has remained the same over a long period of time. They differentiate between ideas and policies that are changing rapidly and ideas that are more fundamental and which do not change. They call this set of core ideas the planning doctrine. A planning doctrine is defined by Faludi and Van der Valk (1994) as a set of interrelated and durable notions about the spatial arrangements within an area, the appropriate development strategy and guidelines about the ways both are to be handled. The ingredients of planning doctrine are accepted by the majority of the planning community, beyond discussion and taken as self evident. (1994, p.18). Planning doctrine has two interrelated dimensions, that is, a principle of spatial organisation and planning principles. Spatial arrangements and their development come together in the principle of spatial organisation, which consists of a complex of spatial concepts, and forms the first dimension of the planning doctrine. The second dimension deals with the planning principles, i.e., the notions concerning the form of plans, preparation and implementation. Planning concepts need certain planning principles to be effective, but planning principles also determine what kind of planning concepts are needed. The two dimensions work together, and it is in this relationship that the planning doctrine as a whole takes form. A Planning doctrine can be considered as a normative theory (Næss and Saglie, 2000). “In addition to this mainly descriptive/analytic endeavour, planning researchers play an important role in the discussion about doctrines. The strong normative 3 element in practical planning also implies that the values, on which various planning solutions and principles are based, should be made subject to assessment and ethical reflection. Planning research should contribute to the on-going, international professional debate on, among others, what sort of planning procedures we should choose, what should be the tasks of planning in society, what values and interests are being promoted through today’s planning, and how planning can improve its ability to promote important social objectives, like for instance democracy, sustainable development and a fair distribution of social benefits.” (Næss and Saglie, 2000), p. 732 This normative theory must have a stable foothold of adherents in the planning community to become effective in co-ordinating decision-making within this community by ensuring consistency in planning decisions (Korthals Altes, 1995). The planning doctrine rests, in this way, on a stable power structure within the arena of policy making. Planning is a longterm process: the time between the first ideas until the implementation stage can amount to many years or even decades. If planning changes fundamentally every time a different minister is in office, then it can never be very effective in the long term. Planning doctrine works as a framework in which planning takes place; it consists of those elements about which there is consensus in the planning community. Planning doctrine is therefore very useful as it delineates discussions, prevents discussion on fundamental issues, and thereby speeds up decision-making processes (Korthals Altes, 1995). The concept of planning doctrine has not only be used for analysing planning in the Netherlands, but has also been used to reflect on pre-doctrinal contexts, such as, inner city redevelopment in Denmark (Vangnby and Jensen, 2002), Czech planning (Maier, 1998) and planning at a European level (Faludi, 1996). It has been used to analyse planning history in 4 Cardiff (Coop and Thomas, 2007), both national planning (Shachar, 1998), and the planning of Jerusalem (Faludi, 1997) in Israel, and for a comparison of growth management in Florida with the Netherlands (Evers et al., 2000). Most of these references are from the end of the nineties. This paper reflects a decade later on planning in the Netherlands to assess the changes that took place, which can also be relevant for using the instrument of planning doctrine in other contexts. Indicators of Doctrinal change A planning doctrine is by definition a durable notion. However, the context of planning does change over time. Political preferences, economic situations and scientific knowledge develop and change over the years, just as society itself changes. The ability to adapt to these changes is potential a weak point of planning doctrines. Consequently Faludi (1989) promoted the idea of an open doctrine. An open doctrine means a doctrine that has the ability to adapt to social, economic and political change. An open doctrine allows for spatial planning to change but at the same time remain within the same doctrine (Faludi, 1989; Alexander and Faludi, 1990; Faludi and van der Valk, 1994). On the one hand, planning doctrine must be relatively closed because it needs to provide stability, and on the other it must be open enough to adapt to changes in society to remain relevant for this society. Two different patterns of doctrinal change have been described (Table 1). The first is a pattern of a stable doctrine that changes revolutionary, much like paradigm change in science, a sudden and total collapse of the old doctrine followed by a new doctrine that is completely different (Faludi and van der Valk, 1994). Such a revolution is not something that should be thought about lightly. A true revolution would change everything in and 5 attached to the planning system including the laws, organisations and the profession. A whole new system of planning would need to be created. In a comprehensive system such as that of the Netherlands, this would be a major task (Faludi, 2007). The risks of such a revolution are high, and if the new planning doctrine does not succeed then planning may lose its position in politics and society all together. Evolutionary change is a second pattern (Korthals Altes, 1992). The evolutionary path is characterised by gradual and partial change of the ideas constituting the core of planning doctrine. The evolutionary path allows planning doctrine to be more open and more able to adapt to changes in society without having to completely overthrow (in a revolutionary way) doctrine and therefore also the existing planning system and community. It is consequently an attractive concept of change, because by slowly changing the core of the planning doctrine, revolution can be avoided (Korthals Altes, 1992). Operational indicators Principle of spatial organization Planning principles Organization of planning subject Composition of the planning community Planning community: learning professional knowledge and skills Relations planning subject within planning network Stable doctrine subject to revolutionary change Stable Revolution Within a rigid frame One set of principles is new concepts are replaced by another developed The method of work Change of approach follows the same model Internal structure Revolution in follows the same organization principles Gradually evolving doctrines Modification Every new concept modifies principle of spatial organization Planning principles are modified by every decision Organization is altered in small steps; eventually character of organization can be completely different Composition evolves gradually Stable composition, only minor variation Split-up in schools Planner is educated once; refresher courses within this framework Subject is focused on same agencies Skills required change at once Planner must re-educate all the time, learn new ways of thinking and unlearn old ones Organisation suddenly focuses on other agencies Web of interdependent agencies around planning subject evolves gradually Table 1: Indicators of doctrinal change (Korthals Altes, 1992) The dynamics of the planning doctrine cannot be studied by only analysing the dynamics of its two dimensions: the principle of spatial organisation and the planning principles, as 6 espoused in plans and other products of planning. In essence a planning doctrine is a way in which a planning subject coordinates decision making within a planning community. Our analysis of the present state of the planning doctrine starts with these earthly basics of what and who the doctrine is organising, i.e., the planning subject and the planning community, i.e., the group where the adherents of the planning doctrine must be in order that the doctrine may play a role in organising decision making. Only after this initial analysis, we will look into the higher end of the planning doctrine, that is, the principles of spatial organisation, and the planning principles. The Planning Subject (toevoegen: wat is het planningsubject in NL, en wat was haar rol) Relation planning subject with planning network The context of the national planning agency has changed considerably. One of the main functions of this agency was the coordination of central government funds, which has been stated above as one of the cornerstones of planning success. Presently these higher authorities are not willing anymore to inject subsidies as part of the social policy. Due to restructuring of the welfares state these subsidies often have been abolished, or have been decentralized to provinces or local authorities. As a result the national planning agency no longer has a role in coordinating other ministries and agencies in spending their money in a territorial sensible way. Another aspect is that many of these sectors have gained access to the planning process due to legal provision that make it necessary that planning agencies must take account of their interests in their land-use plans. This is the case for all kinds of environmental matters, like the impact of a planning proposal for fine particles in the air, archaeological 7 research, a ‘water test’ that must indicate which water management issues are at stake, and the impact of planning on all kinds of birds and other rare species. This is quite often a legal requirement, and not producing these reports and meeting the sector demands may involve that the plan will not pass a planning appeal proceedings in court. This has resulted that ‘the question what is sound planning practice’ (Willey, 2007, p. 1695) is now left to lawyers, based on sectoral definitions and obligations that are often not negotiable but set as legal rules, and not to planners. These changes in the network have affected the influence of the national planning agency on the formulation and implementation of the spatial planning policies in the Netherlands. They demand other strategies from the national planning agency in order to restore its position. Organization of Planning Subject Another element that changes is the planning subject itself. For decades it has been an agency with a dual role, first it was the policy agency of the minister, and as such responsible for the preparation and implementation of government policies, second, it had a role as an agency with an independent role in relation to forecasting, scenario building, and generation of alternative planning options. At a certain moment politicians felt uncomfortable with this positioning in which their own planning agency was critical about official government policies, and they split-up the agency in two different agencies, the planning subject, who is advising the minister, and The Netherlands Institute for Spatial Research (NISR), an independent organization, which performs all kinds of studies on spatial policies and evaluation (Van der Wouden et al., 2006). This new institute, founded January 2002, has taken its independency serious, in such a way that according to an 8 auditing committee (Vistatiecommissie RPB, 2007), the gap between the NISR and policy makers has become much too deep. Studies by the NISR had insufficient impact on practice. The independent course the NISR has followed made the reports and other documents of this institute to reports from outsiders for the remaining policy advisers, that is, the planning subject. Whereas in the past critical accounts came from within the agency, and could not be ignored as being ‘not invented here’, studies of the NISR were easy to ignore, and the institute failed authority. The way of presenting research was not helping to get this authority, i.e., the summary of research went a little further than the underlying results, the press release stressed this even further, and in the press interviews with the director, statements where made that even surpassed this press release, and were not at all based on the research findings written down in the report (Visitatiecommissie RPB, 2007, 11). Now, the NISR has been merged with the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, and in English the latter name will be used. So this part of the former planning subject lost its identity. The result of this movement is that the remaining planning subject has changed gradually. However, this change did not contribute to its capacity to innovate. It lost knowledge, and its internal critics who had a habit to look further than the present politics. Such a planning subject is less capable of evolving gradually, and much more vulnerable for rigidity and so for doctrinal revolutions. The Planning Community (toevoegen inleiding over wat de planning community was.) 9 Market finance has replaced government finance. Whereas serving and for development was in the past just a matter of hierarchical implementation if government grants were organized and spatial permission foreseen, this situation has changed. The market sector dominates more and more the programme, and development companies prefer to have a say in the lay-out of areas for market sector housing as they claim to have a better knowledge of what kinds of housing sells, than government agencies. The national planning agency feels that it is lacking knowledge on the way how private development can pay for spatial developments (De Vries et al., 2008). It is also questioning what the position of national spatial policies will be; many responsibilities have been decentralized (p. 10). In the composition of the planning community market agencies, such as development companies, play a larger role, than in the past. Development companies have acquired personnel form planning agencies. They are not only part of the planning community in relation to local projects, such as the debate for the urban renewal of the Utrecht station area in the 1960s (Bellush, 1968), but now they develop plans for improving the Green Heart (Neprom, 2007). The provinces also change (Korthals Altes, 2006). In the past their knowledge on investment was limited, and their function was based on the integration of different plans in provincial structure plans, and the approval of local development plans. Now they are experimenting with direct development, they are building knowledge capacity in land markets and investments, an they are experimenting with programmes in which urban 10 developments in green areas must be compensated by tearing down unwanted land uses, such as pig stables (Janssen-Jansen, 2008) Toevoegen: conclusie The principle of spatial organisation The principle of spatial organisation in Dutch planning is provided by the complex of ideas about Green Heart and Randstad (Korthals Altes, 1995). De Randstad or ‘rim city’ refers to the circle of cities including the four largest cities of the Netherlands: Amsterdam, Den Haag, Rotterdam and Utrecht, and some mediums sized cities as Haarlem, Leiden and Dordrecht. The Green Heart is the area within the circle of these cities. The preservation of this green area is seen to be of the utmost importance for the cities around it. Next to this central area, the smaller, ‘bufferzones’ between the cities, must be protected. (kaartje toevoegen, anders verschil groene hart en bufferzones totaal onduidelijk) The aim of this principle of spatial organisation is to prevent the transformation of the West of the Netherlands as a selection of urban areas divided by open landscape to a single amorphous sea of houses (Zonneveld, 2007)..The well known archetype of this kind is sprawl is Los Angeles. Critics, like Marco Bontje (2003) have debated the impact of the concepts of Green Heart on spatial development. He argues that urban development in the Green Heart has been substantial, that is, even higher than the average growth in the Netherlands, implying that the various policies meant to protect the Green Heart have not worked. Bontje is however not taking into account that the process of urban deconcentration is very strong, and that expectations to stop this process are hardly realistic (Breheny, 1995a, 1995b). Remarkable is that the share of the 4 largest Dutch cities remained between 1984 and 2004 remained 13% 11 (Korthals Altes, 2007)). In an analysis of land use change between 1995 and 2005 Koomen et al (2008) conclude that the restrictive spatial policies have been effective: “In the Green Heart, as well as the Buffer zones, the rate of urbanisation has been much lower than in non-restrictive areas. When we realise that these areas are under a higher than average urbanisation pressure, the effectiveness is even more impressive. It is good to note, however, that this is a relative and not an absolute success. Urbanisation is not stopped completely but significantly slowed down compared to the non-restricted areas” (Koomen et al., 2008, p. 371). Based on this analysis, it is clear that the principle of spatial organisation has had a substantial impact on spatial development. However, it is not a blueprint that has dominated all. National spatial planning policies have over the years been formulated in a series of national planning documents. The latest of these is the National Spatial Strategy (VROM et al., 2004), which is officially the successor to the Fourth National Policy Document on Spatial Planning conceived in various volumes around 1990. In between these two reports, a fifth report was drawn up in 2001, but never approved by parliament. The National Spatial Strategy is a joint effort of four ministries: Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment; Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality; Transport, Public Works and Water Management; and Economic Affairs. (VROM et al., 2004). It has been approved by Parliament in 2005 and has been in force since February 2006. 12 The organizational principles of Randstad and Green Heart are clearly reflected in the National Spatial Strategy. The general principle of the National Spatial Strategy is to concentrate urban development in concentration areas, which are existing urban areas with their close surroundings. Two or more of these concentration areas and surrounding green spaces form urban networks. The idea is that combining the strengths of different cities within such a network is economically beneficial, and cities must cooperate on issues such as infrastructure, housing, cultural facilities and economic policies. The Green Heart is given the status of a national landscape. Because developments are deemed necessary for the economic position of the Green Heart, new housing, business locations and infrastructure will be allowed as long as they do not have a negative effect on the quality of the landscape. This is a continuation of past policies. The functions that the Green Heart must fulfil do change. Next to the present dominant function of agriculture, other functions, such as, nature, cultural history, recreation and water will be assigned a fair share of it. These anticipated changes do not pose serious threats to the core qualities of the Green Heart. On the contrary they may add to the qualities as perceived by the urban population of the Randstad. Planning principles National planning in the Netherlands is strategic in nature. (Needham, 2007, 121) It gives a vision of the desired future spatial arrangements, and guidelines on how to reach them, rather than mapping out an exact future. It is not blueprint planning, stipulating exactly how the Netherlands should look in 20 years, nor does it state in detail where new houses should be built or infrastructure placed. (Faludi and van der Valk, 1994). Planning future development is planning in uncertainty. The level of uncertainty grows analogous to the 13 level of complexity, the width of the area and the length of the time span under consideration. Strategic spatial planning documents at the national and provincial scale level take a look forwards in time over periods of twenty to thirty years. Political or social developments during these years can affect the plan, but a good strategic plan can guide planning in a changing society as well. Despite all the uncertainty, planning is not just inventing a vision or designing a future like it is popping up out of the planners’ magical black box. The importance of research is founded on the belief that decisions must be explained and accounted for (Faludi and van der Valk, 1994). The Netherlands is a country with a culture of consensus building and finding compromises (Evers et al., 2000). Consensus building and cooperation of various groups, experts, departments and other tiers of government is an important planning principle in the Netherlands. This is reflected in the fact that national planning has no substantial budget for the execution of plans, but coordinates the use of sector department budgets. Cooperation and consensus building is regarded as necessary for effective planning. Without a common goal and idea, planning would not be able to reach its goals (Faludi and van der Valk, 1994). The existing planning procedures ensure that after being presented, national spatial plans have to go through an extensive procedure of consultation and political debate. The procedure allows for consultation with experts and interest groups, participation of the public and political debate, all of which can lead to amendments to the original plan (Faludi and van der Valk, 1994; Hidding, 2002). Apart from this official procedure, the various ministries and agencies, representatives of provinces, municipalities and interest groups are often invited to join in the discussion in the early stages of the planning process. This is to ensure support from some strategically important groups (Korthals Altes, 1995). 14 The Spatial Planning Act provides the back bone for the planning principles in action as it sets the rules that authorities must follow. The Spatial Planning Act is a procedural law. It pertains to the general rules of the game, the organisations and links to laws which are relevant from the perspective of land use planning such as environmental management, expropriation and administrative law. Rules and regulations are specified in detail in a General Decree on Spatial Planning (VROM, 2007). The implementation of legal do’s and don’ts in a decree is standard practice leaving open opportunities for changes in the rules by the cabinet without interference of the chambers of parliament. The law is lacking substantive rules such as densities, heights, prescriptions and restrictions of types of land uses. Spatial planning in the Netherlands previously took place under the Spatial Planning Act of 1965, which was highly decentralised (Lurks, 2001). In many different changes of the law centralising instruments were introduced, such as, the right of the minister to give a direct instruction to local authorities about the contents of local land use plans, a NIMBYproceedings for facilitating locally unwanted land uses, a route law that gives central government specific powers in land use planning for roads and rail roads, a law to fasten proceedings for improving dykes along rivers, and the introduction of national strategic planning through key planning decisions. In addition, there are many other changes, which transformed the law in a patchwork of different articles and proceedings Therefore it was decided to renew the law entirely. This renewed law came into force in July 2008. 15 The renewed act is based on the idea that the planning system must provide legal certainty to property owners, and is so plan-led just like the old one was, at least in theory (Thomas et al., 1983). An innovation, however, is that next to the local land use plans, also the provincial government and national government are allowed to make a binding land use plan to fit a project of provincial or national importance into the spatial fabric. Both government layers also get the authority to make an ordinance which is direct legally binding for owners and users of property. These ordinances may also set area specific regulations, providing owners of a specific plot of land rights that neighbours do not have. Provincial and local authorities must change their plan in conformance with the ordinance within a set time. In this way an ordinance can be considered as an instruction to change a plan with as an addition the direct legal impact on practice. The difference with past practice is that issuing an instruction was very rare, and that now national government has proclaimed to put many aspects, based on the idea ‘centralised where necessary’, in an ordinance (Ministerie van VROM et al., 2008). In the past, in theory, the national government could in theory also provide ‘final’ decisions on land uses. These final decisions were very rare. National government has, however, made clear that they will use the ordinance for many aspects, such as, urban containment policies (Ministerie van VROM et al., 2008). The Association of Netherlands Municipalities is very critical on using ordinances in this way (VNG, 2008). They consider that this is contrary to the principle that norms must be set at the most appropriate level, that is, in general, the local level, because the local facts and circumstances must play a dominant role in spatial planning. The Association of 16 Netherlands Municipalities look at it as an inflexible system of law making that does not contribute to the quality of spatial planning: “We are convinced that this quality largely is determined at the local level and is being assessed in the democratic process. To enhance this there must be ample room for maneuver for local authorities.” They are also concerned about the practicability: “In addition to all tests, guidelines and rules that local authorities must take account of in the preparation of land-use plans, national and provincial ordinances must be followed. The lawful enactment of local land use plans will become pretty impracticable.” (page 2) The provinces are divided in their use of ordinances. Some of them seize the opportunity to get a legal grip in spatial developments with both hands. Others are looking for alternative ways to secure their provincial interest in local land use plans. Under the old-law local land use plans must be approved by the provincial executive, this is no longer necessary. The province must however be informed by the local authorities on new plans, and just as under the old law, they have the authority to provide binding instructions on the content of local land use plans. The grounds for these instructions can be prepared in non binding structural visions. All in all we see at national level a shift in planning principles from development oriented planning, that is, the organisation of the golden strings of spending departments, towards setting of legal rules to planning decision making (see also Galle 2008). The planning principles appear to have changed considerably in this respect, and the planning system might, as the Association of Netherlands Municipality is suggesting, loose the balance 17 between promoting development on sites preferable by planning policies and restricting development on sited that must stay open according to this policies. It has been this balance that have made, according to authors as Needham (1992) and Mori (1998), Netherlands planning such a special combination of stringent urban containment policies and low differences between urban and agricultural land prices. Discussion and conclusion In the introductory sections two possible patterns of doctrinal change have been distinguished, that is, an evolutionary pattern of change versus a pattern of a stable doctrine that can only change through revolutions, that is, a complete and sudden change of planning doctrine. In relation to these changes, it can be established that the principle of spatial organisation is not fundamentally different form the past. The context where planning is working is, and this context is making it much more difficult to renew the doctrine. The in-house capacity for critical assessing the doctrine is lost, and the new NISR is too far away to fulfil this function. Other ministries have limited funds to coordinate, and the planning agency is building up a power position based on legal rulemaking, that is, a position to prohibit development. Critics of the statutory reform emphasize the incompatibility between a consensus based system of strategic planning and the blunt weapons of central and provincial directives in combination with the fresh authority for central government and provinces to conceive zoning plans (Wolsink, 2003; Kersten, 2005; Galle, 2008). The critics perceive a paradigmatic change. 18 The planning system in the Netherlands was previously based on cooperation, consultation and consensus building, on persuasion rather than coercion. In the old system, all tiers of government were forced to cooperate, negotiate and find compromises as there was interdependence between the different tiers. Good communication and good relationships were necessary ingredients in a play with many episodes. Central government and the provinces were dependent upon local authorities for the adoption of binding plan documents. Local authorities could not ignore strategic guidelines of higher authorities at the expense of being deprived of funds. So the municipalities have been attached to central government by ‘golden strings’ Now the balance is in danger of being disturbed by the newly created powers for central government and provinces. The delicate play of giving and taking, that is, the working towards consensus could easily turn into a game of conflict ridden negotiations and appeals in court. The quality of plans might also be affected negatively as there is less room for including local interests in the plan (Wolsink, 2003). Now, the Spatial Planning Act has come into force, planning practice has not changed overnight. In fact, no new local-land use plan has been decided on. So worries about impracticality of the new law can not yet be taken away either. National government has not yet decided on a new ordinance, but the lists of aspects they want to address in the ordinance is published, and show not much restraint. Based on this development we can see that planning doctrine has not changed revolutionary, but has evolved. This gradual change has, however not changed the planning 19 doctrine in such a way that it is contemporary shape is strong. The capacities of innovation of the central planning agency have been diminished and planning will be set more and more in rules, that cannot be adapted to local circumstances. The result might be that an evolving planning doctrine will become a static planning doctrine, which may loose its power to organize consensus making about planning in the Netherlands. Extreme centralisation of planning powers is not compatible with prevalent trends in governance towards collaborative decision making, the demise of the belief in a malleable society, privatisation of government agencies and the growing influence of directives issued by the European Union (Ravensteyn and Evers, 2004). A planning system that follows this route might lose its position. What will happen remains to be seen. So far the responses to the crisis in spatial planning in the nineteen eighties and the subsequent patchwork of repairs meant to adapt the statutory system and the principal of spatial organisation to the demands of (post)modern times are piecemeal, and have been implemented carefully. The complex of countervailing powers in the statutory system has not been disturbed, yet. The content of Dutch spatial planning policy is changing fundamentally but step by step, leaving intact the principles such as concentration of urbanization, spatial cohesion, spatial differentiation, spatial hierarchy, integral development, multiple use of land and intensive use of land. (Needham, 2007, 48) These are not superficial changes though. The 2004 National Spatial Strategy and those of the 2006 Spatial Planning Act touch at the core of Dutch spatial planning doctrine, raising questions in the professional community about risks of doctrinal revolution. Our analysis has revealed weak elements in the process of statutory reform. So far, the general picture conforms to the ideal type of evolutionary change. Evolutionary change follows the path of variation and selection. We see variation, but as has been 20 addressed above, the present variation of the doctrine might not survive the following selection. References Alexander, ER and A Faludi (1990) Planning doctrine: its uses and implications., Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam. Bellush, J (1968) Urban Renewal, Utrecht Style, Urban Aiffairs Quarterly 4, 167-84. Bontje, M (2003) A `Planner's Paradise' Lost?: Past, Present and Future of Dutch National Urbanization Policy, European Urban and Regional Studies 10, 135-51. Coop, S and H Thomas (2007) Planning doctrine as an element in planning history: the case of Cardiff, Planning Perspectives 22, 167-93. De Vries, A, M Van der Wagt and T Maas (2008) Strategische Kennisagenda Ruimte, Ministerie van VROM, Den Haag, (date accessed Evers, D, E Ben-Zadok and A Faludi (2000) The Netherlands and Florida: Two growth management strategies, International Planning Studies 5, 7-23. Faludi, A (1989) Perspectives on Planning Doctrine, Built Environment 15, 57-64. Faludi, A (1996) European planning doctrine: A bridge too far?, Journal of Planning Education and Research 16, 41-50. Faludi, A (1997) A planning doctrine for Jerusalem?, International Planning Studies 2, 83 - 102. Faludi, A (2007) Dynamische planningsdoctrine?, Ruimte in debat 2, 8-9. Faludi, A and A van der Valk (1994) Rule and Order, Dutch Planning Doctrine in the Twentieth Century., Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht. Galle, M (2008) Ruimte voor debat: Nieuwe Wro zet in op achterhaalde sturingsstrategie, Stedebouw & ruimtelijke ordening 89, 58-60. Hajer, M and W Zonneveld (2000) Spatial planning in the network society-rethinking the principles of planning in the Netherlands, European Planning Studies 8, 337-55. Hidding, MC (2002) Planning voor stad en land., Coutinho, Bussum. Janssen-Jansen, LB (2008) Space for Space, a transferable development rights initiative for changing the Dutch landscape, Landscape and Urban Planning 87, 192-200. Kersten, P (2005) Een nota ruimte met nieuwe vergezichten, maar kijk eens een andere kant uit... Oproep tot vakdebat over ruimtelijke ordening., Wageningen UR, Wageningen. 21 Koomen, E, J Dekkers and T van Dijk (2008) Open-space preservation in the Netherlands: Planning, practice and prospects, Land Use Policy 25, 361-77. Korthals Altes, W (1995) De Nederlandse planningdoctrine in het fin de siecle: voorbereiding en doorwerking van de Vierde nota over de ruimtelijke ordening (extra). Van Gorcum, Assen. Korthals Altes, WK (1992) How do planning doctrines function in a changing environment, Planning Theory 7-8, 110-15. Korthals Altes, WK (2006) Towards Regional Development Planning in the Netherlands, Planning, Practice and Research 21, 309-21. Korthals Altes, WK (2007) The impact of abolishing social-housing grants on the compactcity policy of Dutch municipalities, Environment and Planning A 39, 1497-512. Lurks, M (2001) De spanning tussen centralisatie en decentralisatie in de ruimtelijke ordening (with summary in English: The tension between local and central government in public decision-making processes concerning the zoning and use of land), Instituut voor Bouwrecht, Den Haag. Maier, K (1998) Czech planning in transition: Assets and Deficiencies, International Planning Studies 3, 351-65. Ministerie van VROM, LNV, VenW, EZ, OC&W and Defensie (2008) Realisatie nationaal ruimtelijk beleid onder de nieuwe Wro, Ministeries van VROM, LNV, VenW, EZ, OC&W en Defensie, Den Haag, http://www.vrom.nl/pagina.html?id=2706&sp=2&dn=8211 (date accessed 03/04/2009). Næss, P and I-L Saglie (2000) Surviving Between the Trenches: Planning Research, Methodology and Theory of Science, European Planning Studies 8, 729-50. Neprom (2007) De toekomst van het Groene Hart, Neprom, Voorburg, http://www.neprom.nl/webgen.aspx?p=27&o=196 (date accessed 03/04/2009). Shachar, A (1998) Reshaping the Map of Israel: A New National Planning Doctrine, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 555, 209-18. Thomas, D, J Minett, S Hopkins, S Hamnett, A Faludi and D Barrell (1983) Flexibility and Commitment in Planning, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, The Hague/Boston/London. Toonen, TAJ (1990) The unitary state as a system of co-governance: the case of the Netherlands, Public Administration 68, 281-96. Van der Wouden, R, E Dammers and N Van Ravesteyn (2006) Knowledge and Policy in the Netherlands: The Role of the Netherlands Institute for Spatial Research, DISP 165, 34-42. Vangnby, B and OB Jensen (2002) From Slum Clearance to Urban Policy: Discourses and Doctrines in Danish Inner City Redevelopment, Housing theory and society 19, 3-13. 22 Vistatiecommissie RPB (2007) Het RPB tussen wetenschap en beleid, Den Haag, http://www.vrom.nl/Docs/ruimte/evaluatierapport_RPB_don_2007.pdf (date accessed VNG (2008) Letter “Nationaal ruimtelijk beleid onder de nieuwe Wro" from 29-04-2008 to the minister of planning, The Hague, http://www.vng.nl/Documenten/vngdocumenten/2008_overig/kabinet_BARWU200800683.pdf (date accessed 02/04/2009). VROM (2007) Ontwerp-Besluit ruimtelijke ordening, Staatscourant 85, 14. VROM, LNV, VenW and EZ (2004) Nota Ruimte. Ruimte voor Ontwikkeling., Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en Milieubeheer, Den Haag. Willey, S (2007) Planning appeal processes: reflections on a comparative study, Environment and Planning A 39, 1676-98. Wolsink, M (2003) Reshaping the Dutch planning system: a learning process?, Environment and Planning A 35, 705-23. Zonneveld, W (2007) A sea of houses: preserving open space in an urbanised country, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 50, 657-75. Acknowlegdement p.m. 23 In the sections above we have seen considerable changes in the context of national spatial planning, and, at the same time, a continuity of thought on the principle of spatial organisation. How this tension does have influenced the planning principles? The answer is that there has been much debate on the matter of centralisation that is required to counterforce the larger role of the market and local authorities on the field of many land uses. We will first go into the traditional planning principles, introduce than the debate, go into the process of making a new law, and conclude with a discussion on this part of doctrinal change. 24