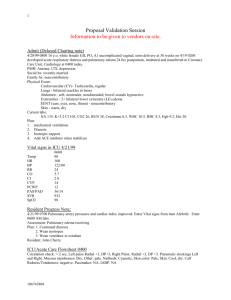

A Minute for the Medical Staff

advertisement

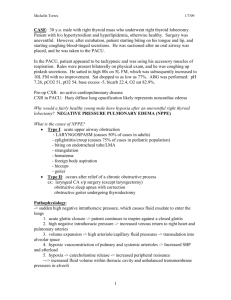

A Minute for the Medical Staff A supplement to medical records briefing January 2001 Always name the pathophysiology of the disease By Robert Gold, MD Vice President Healthcare Management Advisors Alpharetta, GA The purpose of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is to communicate statistics about disease processes, their etiologies, demographic elements, treatment choices, and outcomes among all areas of the world. In order to have a chance of delivering good statistics, the proper codes must be applied to the diseases your patients have, and to the operative interventions used to treat those diseases. In some cases, it’s a breeze. Acute appendicitis without diffuse peritonitis or obstruction is treated with an appendectomy, and has a certain expected outcome. People all over the world can easily compare their morbidity and mortality statistics for that disease and treatment. But sometimes, it’s not so easy. In the usual course of practice, physicians evaluate and treat certain disease processes with innate knowledge of the usual etiologies and the pathophysiology of the disease. In these cases, in order to apply the proper codes, the physician has to go through a bit more description than usual. Understanding and appreciating the difference that extra documentation can make is the difference between thinking of it as a burden and taking it as a matter of course necessary for accurate comparative data. Angina Most physicians call coronary artery occlusive chest pain “angina.” Some don’t. Some name new onset angina, worsening angina, angina at rest, and preinfarction angina “unstable.” Some don’t. It is important to name the clinical situation. If it’s heart-induced chest pain resulting from the inability to supply the myocardiu7m with oxygenated blood, call it “angina.” If it meets the definitions above, call it “unstable.” Angina can be induced to occur because of other clinical situations that result in the heart not getting enough oxygenated blood and causing cardiac chest pain that is truly angina. If your patient has uncontrollable angina because of the anemia of chronic renal failure and the only way to treat it is by transfusion, then name the pathophysiology: “Angina, unstable due to severe anemia of chronic renal failure.” If you patient has uncontrollable angina and the EKG reveals a tachyarrhythmia (e.g., atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response) or bradyarrhythmia such that the coronaries cannot get enough blood flow and you have to break the rhythm abnormality to stop the chest pain, then name the pathophysiology: “Angina, unstable, due to arrhythmia.” If your patient has uncontrollable angina or unstable angina because of the increased metabolic demands of a high fever or of thyrotoxicosis, then name the pathophysiology: “Angina, unstable, because of the increased metabolic demands of (whatever the cause.)” Why should you go through the trouble of naming the pathophysiology? It makes sense. You are telling the world why you selected the treatment modalities you selected in those cases. In addition, it tells them why you didn’t select certain modalities. And finally, when you involve a higher level of evaluation and management skills, and document that you justifiably involved several body systems, you can bill at a higher level of E/M. Pulmonary edema Again, we have a condition that is usually associated with one pathologic process, but even that pathologic process has several etiologies. Congestive heart failure (CHF) can be due to arteriosclerotic, hypertensive heart disease, ischemic heart disease, a primary cardiomyopathy, or cor pulmonale. We know that left heart failure is the usual cause of acute pulmonary edema, regardless of the etiology, but there are other disease processes that are noncardiogenic that can result in acute pulmonary edema. In cases of noncardiac pulmonary edema, it becomes essential to demonstrate with the proper words your thoughts about the cause—the pathophysiologic process that has led to soggy lungs. Because if you do not elucidate the cause of the pulmonary edema, coders will automatically apply the code for CHF to the case, and that’s just not what’s going on. When a patient develops acute pulmonary edema from a pulmonary embolus, name the pathophysiology: “Noncardiac pulmonary edema from pulmonary embolism.” When a patient develops acute pulmonary edema from a crush injury, name the pathophysiology: “Noncardiac pulmonary edema from pulmonary contusion.” When a patient develops acute pulmonary edema from volume overload from chronic renal failure, has a normal ejection fraction under normal conditions, has not had ischemic heart disease, and is basically not a CHF patient, name the pathophysiology: “Noncardiac pulmonary edema from volume overload from chronic renal failure.” When a patient aspirates a significant amount of gastric acid and burns the lungs, whether or not there has been time to develop a superinfection, name the pathophysiology: “Noncardiac pulmonary edema from aspiration of gastric acid.” When a patient develops Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), he or she needs a ventilator from overwhelming sepsis, and the chest x-ray shows pulmonary edema, name the pathophysiology: “Noncardiac pulmonary edema of ARDS resulting from overwhelming sepsis.” The reasons for going through this additional “burden” of adding a few words is that it makes a tremendous difference to the ICD coding, and thus to the statistics in the United States, of patients with pulmonary edema related to CHO or from noncardiac causes. It makes a difference in the amount of resources that you can utilize without question because you have reflected a more severely ill patient. It makes a difference to the bill you can submit for your thought processes and your work because you have documented and validated a higher level of thought and management. More examples of the differences that documentation can make to the proper assignment of ICD codes will follow in subsequent issues. In the meantime, be careful out there. A Minute for the Medical Staff is an exclusive service for subscribers to Medical Records Briefing. Reproduction of A Minute for the Medical Staff within the subscriber’s institution is encouraged. Reproduction of any form outside the subscriber’s institution is forbidden without prior written permission.